Ok, so I’m taking the time to go back through this article properly.

1. It’s not very well written, and needs some solid editing. There are random threads that should have been snipped off. eg the bit about paleo diets. What did she want to say there? Was it a thing about the commodification of a mythic ‘essential human past’? Then why not say so?

2. She does not address ethnicity or race in any way. Fail. This is a substantial flaw, because most of the current day multi-generational families, home-businesses, and so on are are marked by class, and by race.

3. She says the ‘tradwives’ trend is dumb, because ‘tradwives’ want to be like the ‘wives’ of the 1950s. She says ‘why not aim to be ‘tradwives’ of the 1300s because it’s more legit?

I am struggling to get on board with this. I’m a fan of things like contraception and not being my lord’s chattel.

4. Her fangirling about the 1300s seems to be a response to a twitter thread defending the word ‘spinster’ as referring to single women who were economically independent that’s recently done the rounds, but which has since proved to be full of shit.

A cleverer response thread was doing the rounds, but I can’t find it right now. So here’s a post about a more accurate etymology of spinster.

The upshot is that it wasn’t that great to be a woman in the 1300s, even one working with her sisters in a shared workspace.

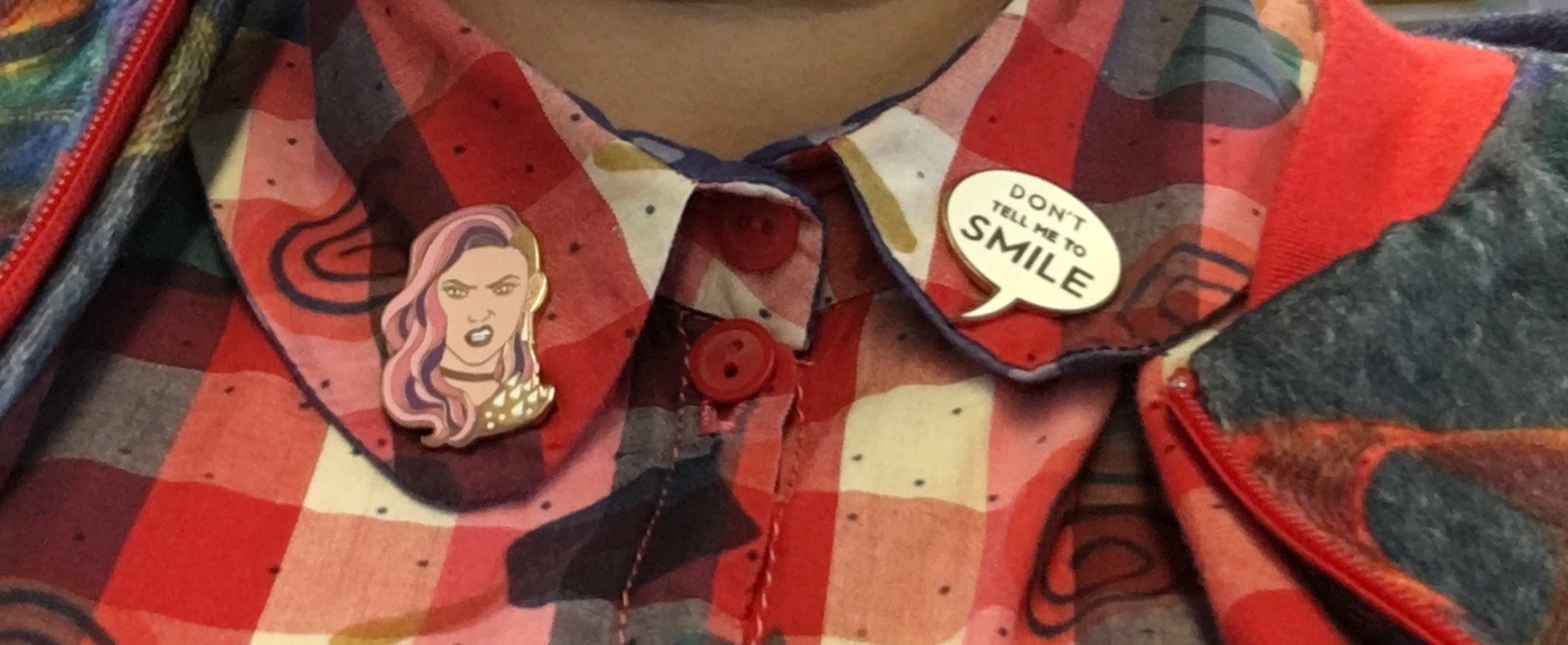

5. She continues, getting to the real meat of her piece: no more laws! They’re harshing our feminist collective mellow!

How, then, can a suburban family with a tiny garden transform their private home into a 14th-century-style household economy? The digital economy offers some help on this front: Pettitt herself extols the virtues of ‘tradwife’ while running a digital business from home. But more could be done to support a blossoming of tradewives (or tradehusbands).

She might have said ‘how can white ladies with white husbands and wee little white kiddies earn money from home?

Well, it’s not going to happen in Australia with our NBN. Or in rural centres in Australia. Or even, increasingly, in our urban centres.

To run an online business you need:

– good, and reliable electricity, and internet infrastructure

– reliable hardware (computers and so on)

– LITERACY – reading and writing – and NUMERACY

– to get that last one, you’ll need to have attended a decent school, to have been able to study at that school (and not stay home to work in your family’s business, or be waylaid by unwanted pregnancies or caring for other family members)

– you’ll need to have reproductive independence: access to safe and affordable contraception.

…and so on.

That’s all before we get to the actual business part of the business. ie the things you make, and the way you run your enterprise.

[edit]WE KNOW that reducing poverty is directly tied to the education and reproductive independence of women and girls. Get girls reading, get them on the pill (or otherwise able to control when and how they have babies), and they have more social and economic power. This is, clearly, not as simple as I make it sound. But we know that poverty in general is a direct result of capitalist patriarchy.[/]

But this lady is pretty sure it’s that interfering government getting in the way of nice white ladies forming child care collectives.

My DOOD. That’s some neoliberal bullshit right there.

She also thinks that it’d help to get rid of other forms of pesky government interference: the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) is the one she latches onto.

She also has a thing about the restrictions of residential and commercial property use. It should be done away with! And why not?! Haven’t we all wanted a commercial meatpacker next door, or panel beaters across the street?

…at this point, I’m wondering if she’ll start talking about sex work, which seems the logical extension of her point: safe, collective spaces run by women, enabling them to work off the streets, and control their own incomes (and bodies).

But she doesn’t go there. She’s thinking about nice middle class white lady internet businesses.

This bit is just plain bucolic:

And surely it is not beyond the wit of policy wonks to come up with a means for tradewives to cooperate on collectives such as craft or market gardening, which could be done in the company of small children.

Such whimsy.

6. She ends by asking:

But if we can build on the emancipatory desires of women since the 1960s, taking our inspiration not from the 1950s but the 1350s, perhaps we could rethink the split between home and work and support a rebirth of the far older tradition of ‘tradewives’. We might even find this brings with it a renaissance of community connection and social capital across our struggling villages and small towns.

Ok, so we’re going to do some feminist deconstruction of capitalism and industrialisation. Sure. How do we do that, fren?

I’m not sure what she means, exactly when she talks about ‘community connection’ and ‘social capital’. She’s pretty sure she wants it, but what does she _mean_? Neighbours talking to each other? A return of incumbent lords and serfs with everyone knowing their place?

It’s not a good piece, and I don’t think she makes any good points. Besides a weak-sauce dismissal of 1950s ‘housewifery’.

She has not looked into the everyday lives of women who _do_ work from home.

She provides no real evidence that ‘tradwives’ is even a thing. Yes, there are lots of blogs by women deciding to stay home and knit sweaters for their home schooled kiddies. But most of them have husbands in very well paid jobs. And most of them are white living in north america. And there’s a hashtag. But I’m going to need more research, mate.

She doesn’t look at the live of migrant women in Britain working in cosy ‘domestic collectives’ supplying garments for the garment trade, doing phone sex (or sex work generally) off-site, or flogging cleaning products for Amway. There certainly aren’t any brown women in her stories, and there aren’t any already struggling with poverty and racism.

So, in sum, I declare this article:

Rubbish.