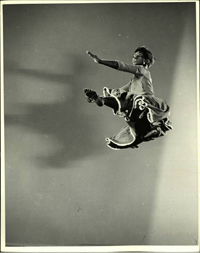

(image from the Powerhouse Museum).

Finally!

Years after I was first asked, I’ve finally gotten myself organised and gotten the guts to put together a set for Yehoodi radio. I know, I know, it’s silly to get worked up about these things. But that’s how I roll. Worry, obsessing, all that shit. I’m all over it. But, mostly thanks to Jesse’s patience, I’ve gotten it happening.

During my set (which goes for about four and a half hours), I do a bit of talking and explain why I chose particular songs. I couldn’t put in everything I wanted to say (who’d have thought? I like to talk as much as I like to write!), so I’ve decided to flesh out the radio show here with some details, useful links and references.

The set is on every Thursday in June on Yehoodi radio, from 4-6:30pm 7pm-4am Thursdays, then 5am-3pm, 4-6.30pm Fridays, Sydney time. I think. Maybe check yourself?.

Firstly, Here’s the set:

1. intro2-1:59

2. Davenport Blues – Adrian Rollini and his Orchestra (Jack Teagarden) – Father Of Jazz Trombone – 136 – 1934 – 3:14

3. I Like Pie I Like Cake (but I like you best of all) – The Goofus Five (Bill Moore, Adrian Rollini, Irving Brodsky, Tommy Felline, Stan King) – Goofus Five 1924-1925 – 188 – 1924 – 3:15

4. Let’s Sow A Wild Oat – Jimmie Noone’s Apex Club Orchestra (Joe Poston, Alex Hill, Junie Cobb, Bill Newton, Johnny Wells, George Mitchell, Fayette Williams) – The Jimmie Noone Collection – 185 – 1928 – 3:03

5. Borneo – Frankie Trumbauer and his Orchestra (Bix Beiderbecke, Charlie Margulis, Bill Rank, Chet Hazlett, Irving Friedman, Lennie Hayton, Eddie Lang, Min Liebrook, Hal McDonald, Scrappy Lambert, Bill Challis) – The Complete Okeh and Brunswick Bix Beiderbecke, Frank Trumbauer and Jack Teagarden Sessions (1924-1936) (disc 2) – 184 – 1928 – 3:11

6. A Mug Of Ale – Joe Venuti’s Blue Four – All Star Jazz Quartets (disc 3) – 220 – 1927 – 3:07

7. Never Had A Reason To Believe In You – Mound City Blue Blowers (Jack Teagarden, Red McKenzie, Eddie Condon, Jack Bland, Pops Foster, Josh Billings) – Father Of Jazz Trombone – 180 – 1929 – 3:03

8. 1-backannounce-B – 0:36

9. I Hope Gabriel Likes My Music – Frankie Trumbauer and his Orchestra (Ed Wade, Charlie Teagarden, Jack Teagarden, Johnny Mince, Jack Cordaro, Mutt Hayes, Roy Bargy, George van Eps, Artie Miller, Stan King) – The Complete Okeh and Brunswick Bix Beiderbecke, Frank Trumbauer and Jack Teagarden Sessions (1924-1936) (disc 7) – 190 – 1936 – 3:14

10. I’se A Muggin’ – Le Quintette du Hot Club de France (Stéphane Grappelli, Django Reinhardt, Joseph Reinhardt, Pierre Ferret, Lucien Simoens, Freddy Taylor) – The Complete Django Reinhardt And Quintet Of The Hot Club Of France Swing/HMV Sessions 1936-1948 (disc 1) – 176 – 1936 – 3:08

11. Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone – Glenn Miller’s G.I.s (Peanuts Hucko, Mel Powell, Bernie Priven, Joe Schulman, Ray McKinley, Django Reinhardt) – Glenn Miller’s G.I.s in Paris 1945 – 182 – 1945 – 2:59

12. 2-backannounce 3 – 1:55

13. Benny’s Bugle – Benny Goodman Sextet (Cootie Williams, George Auld, Count Basie, Charlie Christian, Artie Bernstein, Harry Jaeger) – Charlie Christian: The Genius of The Electric Guitar (disc 2) – 203 – 1940 – 3:06

14. Squatty Roo – Johnny Hodges and his Orchestra (Ray Nance, Lawrence Brown, Harry Carney, Duke Ellington, Jimmy Blanton, Sonny Greer) – The Duke Ellington Centennial Edition: Complete RCA Victor Recordings (disc 12) – 202 – 1941 – 2:24

15. Flying Home – Teddy Wilson Sextet (Emmett Berry, Benny Morton, Edmond Hall, Slam Stewart, Big Sid Catlett) – The Complete Associated Transcriptions – 1944 – 198 – 1944 – 4:56

16. 2B-backannounce – 0:22

17. Shortnin’ Bread – Fats Waller and His Rhythm (John Hamilton, Gene Sedric, Al Casey, Cedric Wallace, Slick Jones) – Last Years (1940-1943) (Disc 2) – 195 – 1941 – 2:41

18. Don’t Try Your Jive On Me – Una Mae Carlisle with Dave Wilkins, Bertie King, Alan Ferguson, Len Harrison, Hymie Schneider – Una Mae Carlisle: Complete Jazz Series 1938 – 1941 – 188 – 1938 – 2:52

19. That’s What You Think – Putney Dandridge and his Orchestra (Henry ‘Red’ Allen, Buster Bailey, Teddy Wilson, Lawrence Lucie, John Kirby, Walter Johnson) – Complete Jazz Series 1935 – 1936 – 185 – 1935 – 2:43

20. I’m Gonna Clap My Hands – Gene Krupa’s Swing Band (Chu Berry, Helen Ward) – Classic Chu Berry Columbia And Victor Sessions (Disc 1) – 188 – 1936 – 3:01

21. 3-backannounce 2 – 1:40

22. Warmin’ Up – Teddy Wilson and his Orchestra (Roy Eldridge, Buster Bailey, Chu Berry) – Classic Chu Berry Columbia And Victor Sessions (Disc 2) – 241 – 1936 – 3:20

23. Dancing Dogs – Mills Blue Rhythm Band (Lucky Millinder, Henry ‘Red’ Allen, Buster Bailey) – Mills Blue Rhythm Band: Harlem Heat – 228 – 1934 – 2:49

24. Lafayette – Bennie Moten’s Kansas City Orchestra (Count Basie, Ben Webster, Walter Page) – Bennie Moten’s Kansas City Orchestra (1929-1932): Basie Beginnings – 296 – 1932 – 2:47

25. Stompy Jones – Duke Ellington and his Orchestra – The Duke Ellington Centennial Edition: Complete RCA Victor Recordings (disc 07) – 200 – 1934 – 3:03

26. Stompin’ At The Savoy – Jimmy Dorsey and his Orchestra – Swingsation: Charlie Barnet and Jimmy Dorsey – 162 – 1936 – 3:12

27. 4-backannounce – 2:41

28. St. Louis Blues – Ella Fitzgerald and her Famous Orchestra – Ella Fitzgerald In The Groove – 183 – 1939 – 4:46

29. Pound Cake – Count Basie and his Orchestra (Lester Young) – Classic Columbia, Okeh And Vocalion Lester Young With Count Basie (1936-1940) (Disc 2) – 186 – 1939 – 2:46

30. Page Mr. Trumpet 2:53 Pete Johnson Complete Jazz Series 1944 – 1946

31. 627 Stomp – Pete Johnson’s Band (Oran ‘Hot Lips’ Page, Edddie Barefield, Don Stovall, Don Byas, John Collins, Abe Bolar, A. G Godley) – Jazz – Kansas City Style – 153 – 1940 – 3:13

32. Shake It And Break It – Joe Turner with the Varsity Seven (Pete Johnson, Benny Carter, Coleman Hawkins) – Complete Jazz Series 1938 – 1941 – 177 – 2:59

33. Some Of These Days – Julia Lee, Clint Weaver, Sam ‘Baby’ Lovett – Kansas City Star (disc 1) – 210 – 1946 – 2:02

34. Baby Heart Blues – Jay McShann and his Orchestra (Walter Brown) – Jumpin’ The Blues (disc 01) – 159 – 1941 – 2:47

35. Jumpin’ Little Woman – Tiny Kennedy – Kansas City Blues 1944-1949 (Disc 3) – 118 – 1949 – 2:37

36. Undecided Blues – Count Basie and his Orchestra (Jimmy Rushing) – Cutting Butter – The Complete Columbia Recordings 1939 – 1942 (disc 03) – 120 – 1941 – 2:56

37. 5-backannounce – 2:01

38. I’m Going To Start A Racket – Lil Green (acc. by Simeon Henry, Jack Dupree, Big Bill Broonzy, Ransom Knowling) – 1940-1941 – 104 – 1941 – 3:00

39. My Man Jumped Salty On Me – James P. Johnson’s Hep Cats (Rosetta Crawford, Mezz Mezzrow) – History of the Blues (disc 02) – 112 – 1939 – 3:23

40. Come Easy Go Easy – Rosetta Howard acc. by the Harlem Blues Serenaders (Charlie Shavers, Buster Bailey, Lil Armstrong, Ulysses Livingston, Wellman Brand, O’Neil Spencer) – Rosetta Howard (1939-1947) – 90 – 1939 – 3:03

41. Moaning The Blues – Victoria Spivey acc by Henry ‘Red’ Allen, JC Higginbotham, Teddy Hill, Luis Russell – Henry Red Allen And His New York Orchestra (disc 1) – 97 – 1929 – 3:07

42. 6-backannounce 2 – 1:29

43. Need a Little Sugar in My Bowl – Janet Klein – Come Into My Parlor – 94 – 1998 – 2:12

44. You Got to Give Me Some – Midnight Serenaders (David Evans, Dee Settlemier, Doug Sammons, Garner Pruitt, Henry Bogdan, Pete Lampe) – Magnolia – 187 – 2007 – 4:02

45. Old Joe’s Hittin’ The Jug – Rhythm Club All Stars – Introducing The Rhythm Club All Stars – 269 – 2008 – 2:43

46. Red Hot Band – Bob Hunt’s Duke Ellington Orchestra – What A Life! – 237 – 1999 – 2:40

47. Looking Good But Feeling Bad – Les Red Hot Reedwarmers – Apex Blues – 272 – 2007 – 3:52

48. 7-backannounce – 3:23

49. I’ll Build A Stairway To Paradise – Rufus Wainwright (I think singing with the Manhattan Rhythm Kings, or perhaps Vince Giordano’s band?) – The Aviator – 142 – 3:12

50. Let’s Do It – Terra Hazelton (feat. Jeff Healey, Marty Grosz, Dan Levinson, Vince Giordano) – Anybody’s Baby – 126 – 2004 – 4:28

51. Some Of These Days – Midnight Serenaders (David Evans, Dee Settlemier, Doug Sammons, Garner Pruitt, Henry Bogdan, Pete Lampe) – Sweet Nothin’s – 255 – 2009 – 3:29

52. Chinatown, My Chinatown – Hot Club Of Cowtown – Swingin’ Stampede – 256 – 1998 – 3:02

53. Stay A Little Longer – Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys – The Tiffany Transcriptions (vol 2) – 232 – 3:07

54. 8-backannounce – 1:14

55. Chimes at the Meeting (feat. Washboard Chaz) – Ophelia Swing Band – Swing Tunes of the 30’s & 40’s – 253 – 1977 – 3:23

56. Digadoo – Firecracker Jazz Band – The Firecracker Jazz Band – 247 – 2005 – 5:20

57. Puttin’ on the Ritz – Mona’s Hot Four (Dennis Lichtman, Gordon Webster, Cassidy Holden, Nick Russo, Jesse Selengut, Dan Levinson, Tamar Korn) – Live at Mona’s – 185 – 2009 – 7:49

58. Better Off Dead – Linnzi Zaorski and Delta Royale (Charlie Fardella, Robert Snow, Matt Rhody, Seva Venet, Chaz Leary) – Hotsy-Totsy – 146 – 2004 – 3:51

59. 9-backannounce – 1:31

60. Do You Call That A Buddy – Chris Tanner’s Virus – With Her Dixie Eyes Blazin’ – 119 – 2001 – 6:17

61. The Love Me Or Die – C.W. Stoneking – Jungle Blues – 153 – 2008 – 3:55

62. Blue Leaf Clover – Firecracker Jazz Band – The Firecracker Jazz Band – 111 – 2005 – 4:59

63. That Too, Do – Bennie Moten’s Kansas City Orchestra (Count Basie, Jimmy Rushing) – Moten Swing – 123 – 1930 – 3:20

64. 10-backannounce – 2:59

65. It’s Tight Like That – Jimmie Noone’s Apex Club Orchestra (Joe Poston, Alex Hill, Junie Cobb, Bill Newton, Johnny Wells, George Mitchell, Fayette Williams) – The Jimmie Noone Collection – 144 – 1928 – 2:49

66. Truckin’ – Henry ‘Red’ Allen and his Orchestra – Henry Red Allen ‘Swing Out’ – 171 – 1935 – 2:54

67. Murder In The Moonlight – Red McKenzie and his Rhythm Kings (Eddie Farley, Mike Riley, Slats Young, Conrad Lanoue, Eddie Condon, George Yorke, Johnny Powell) – Classic Sessions 1927-49 (Volume 2) – 193 – 1935 – 2:55

68. Joe Louis Stomp – Bill Coleman, Edgar Currance, Jean Ferrier, Oscar Aleman, Eugene d’Hellemes, Hurley Diemer – Bill Coleman In Paris 1936-1938 – 213 – 1936 – 3:14

69. Beau Koo Jack – Louis Armstrong and his Savoy Ballroom Five (Fred Robinson, Jimmy Strong, Don Redman, Earl Hines, Mancy Cara, Zutty Singleton, Alex Hill) – Hot Fives and Sevens – Volume 3 – 246 – 1928 – 3:01

70. Blues (My Naughty Sweetie Gives to Me) – Wilbur De Paris and his Rampart Street Ramblers – Dr. Jazz Vol. 7 – 153 – 5:35

71. St. Louis Blues – Sidney Bechet and his New Orleans Feetwarmers (Vic Dickenson, Don Donaldson, Wilson Meyers, Wilbert Kirk) – The Sidney Bechet Story (disc 3) – 131 – 1943 – 4:49

72. 11-backannounce – 1:54

73. Reckless Blues – Louis Armstrong and his All Stars (Velma Middleton, Trummy Young Edmund Hall, Billy Kyle, Everett Barksdale, Squire Gersh, Barrett Deems) – The Complete Decca Studio Recordings of Louis Armstrong and the All Stars (disc 06) – 88 – 1957 – 2:30

74. Jealous Hearted Blues – Carol Ralph – Swinging Jazz Portrait – 80 – 2005 – 3:48

75. You Help Your New Woman – Di Anne Price – 88 Steps to the Blues – 87 – 2009 – 4:36

76. What Kind Of Man Is This? – Koko Taylor – South Side Lady (Live in Netherlands 1973) (Blues Reference) – 116 – 1973 – 4:08

77. Sweet Home Chicago – David “Honeyboy” Edwards – Sun Records – The Blues Years, 1950 – 1958 CD4 – 112 – 3:01

78. Blues Stay Away – George Smith – Kansas City – Jumping The Blues From 6 To 6 – 82 – 1955 – 3:10

79. Evil Woman – Lonnie Johnson – The Bluesville Years Volume 11: Blues Is A Heart’s Sorrow – 104 – 2:34

80. Inform Me Baby – Walter Brown – Kansas City Blues 1944-1949 (Disc 2) – 71 – 1949 – 2:59

81. I Ain’t No Ice Man – Cow Cow Davenport with Joe Bishop, Sam Price, Teddy Bunn, Richard Fullbright – History of the Blues (disc 02) – 89 – 1938 – 2:51

82. Hamp’s Salty Blues – Lionel Hampton and his Quartet – Lionel Hampton Story 3: Hey! Ba-Ba-Re-Bop – 86 – 1946 – 3:10

83. 12-backannounce 2 – 1:00

84. Kitchen Blues – Martha Davis – BluesWomen: Girls Play And Sing The Blues – 80 – 1947 – 3:05

85. Fine And Mellow – Mal Waldron and the All-Stars (Billie Holiday, Roy Eldridge, Lester Young, Coleman Hawkins, Milt Hinton) – The Sound Of Jazz – 79 – 1957 – 6:22

86. Rocks In My Bed – Ella Fitzgerald acc. by Ben Webster, Paul Smith, Stuff Smith, Barney Kessel, Joe Mondragon, Alvin Stoller – Ella Fitzgerald Day Dream: Best Of The Duke Ellington Songbook – 68 – 1956 – 3:59

87. 13-backannounce – 1:19

88. Willow Weep For Me – Louis Armstrong, Oscar Peterson, Herb Ellis (g), Ray Brown (b), Buddy Rich – Ella And Louis Again – 90 – 1957 – 4:21

89. No Regrets – Cecile Mclorin Salvant and the Jean-Francois Bonnel Paris Quintet – Cecile – 134 – 2010 – 4:05

90. Sweet Lorraine – June Christy and The Kentones – Complete Peggy Lee and June Christy Capitol Transcription Sessions (Disc 1) – 138 – 1945 – 2:34

91. Joog, Joog – Duke Ellington and his Orchestra – Duke Ellington and his Orchestra: 1949-1950 – 146 – 1949 – 3:01

I put together this set with an ear to transitioning smoothly between songs. I planned it as though it was a real set I was playing for dancers. But I also thought about who was in the bands and about grouping particular styles.

1

– Adrian Rollini’s band featuring Jack Teagarden. One of my go-to songs.

– Goofus Five (featuring Adrian Rollini). My preferred version, and one Trev put me onto.

– Jimmy Noone: for whom I have great, towering feelings.

– Trumbauer’s band featuring Bix Beiderbecke and Eddie Lang, doing my FAVOURITE SONG, ‘Borneo’.

– Joe Venuti’s band.

– The Mound City Blue Blowers, featuring Jack Teagarden, and doing ‘St Louis Blues’ on youtube.

– Jack Teagarden. Beautiful voice, gorgeous trombone, not at all beautiful to look at. Would marry.

2

– Trumbauer’s band again, with more Jack Teagarden

small groups:

– Quintette of the Hot Club of France featuring Django Reinhardt.

– Glenn Miller’s G.I.s featuring Django Reinhardt and other Americans, in Paris.

– Bennie Goodman’s sextet (Count Basie, Charlie Christian, Cootie Williams)

-> the importance of Goodman’s small groups lie in their music, but also in the fact that they were mixed-race. Check out this cool clip of one of Goodman’s small groups’ performances.

– Johnny Hodges and his Orchestra – Duke Ellington’s small group, featuring Johnny Hodges. Cootie Williams played in Ellington’s band.

2b

– Teddy Wilson Sextette. Massive love for Teddie Wilson. The iconic song ‘Flying Home’ by Teddie Wilson’s sextette, featuring Slam Stewart, part of Slim and Slam, silly vocal kings.

– Fats Waller doing ‘Shortnin’ Bread’, one of my faves.

3

kicking bands with great vocals:

– Una Mae Carlisle with a small group (Carlisle recorded other songs with Slam Stewart, with Zutty Singleton (who played with Fats Waller a bit) and Lester Young (from Basie’s band!)). The piano intro reminds me of Fats Waller, and the muted trumpet solo is very Waller small band-like.

-> Carlisle as one of the first swing vocalists I liked when I started dancing.

– Putney Dandrige, with a brilliant band featuring Henry ‘Red’ Allen, Buster Bailey, Teddy Wilson, Lawrence Lucie, John Kirby and Walter Johnson. Carlisle also recorded with Buster Bailey and John Kirby. Dandridge is interesting because later in his career he was obviously imitating Fats Waller’s vocal style. And not doing a good job.

– Helen Ward singing with Gene Krupa’s band, which also features Chu Berry.

4

Bigger bands, with musicians in common:

– Teddy Wilson again, with Chu Berry in this band, as well as Buster Bailey and Roy Eldridge

– the Mills Blue Rhythm Band (with Lucky Millinder, Henry ‘Red’ Allen, Buster Bailey), doing hot hot jazz

– Bennie Moten’s band featuring Count Basie, Ben Webster, Walter Page, playing a familiar song ‘Lafayette’. I love this Kansas action.

– A Duke Ellington wonderment – my favourite Ellington song

Big band classic swing WIN:

– Jimmy Dorsey doing the BEST version of ‘Stompin at the Savoy’, my favourite shim sham song. Remember Dorsey was in the Mound City Blue Blowers at one point.

– a brilliant version of another common song, ‘St Louis Blues’, by Ella Fitzgerald (not singing) with what was Chick Webb’s band. Played live at the Savoy (hence the link to ‘Stompin at the Savoy’).

Kansas!

– Basie’s band playing ‘Pound Cake’. A classic example of solid, wickedly good Basie big band lindy hopping win. Basie of course turned up earlier, but this is the classic ‘old testament’ Basie sound, not Moten stuff, and not small Goodman Group stuff. The rhythm section is where it’s at in this song.

– Pete Johnson. YES.

– Pete Jonson AGAIN, this time featuring Hot Lips Page doing ‘627 Stomp’. Read about the 627 Local here.

– Big Joe Turner (with Pete Johnson I think)! doing ‘Shake It and Break It’, a song I love because of this performance

– Julia Lee! Brilliant home-recording session

– Jay McShann! Walter Brown! Kansas city win!

– Tiny Kennedy!

– Count Basie with Jimmy Rushing. Singing waiters. Wonderful.

5

Slower music, possibly for blues dancing. Raggedy, kick your arse vocals, attitudinal singers, excellent bands:

– Lil Green. Getting into crime to fund a better lifestyle.

– James P Johnson’s Hep Cats with Mezz Mezzrow, but more importantly, ROSETTA CRAWFORD. Cut him if he stands still, shoot him if he runs

– Rosetta Howard (!!) with the Harlem Blues Serenaders, band of amazingness: Charlie Shavers, Buster Bailey, Lil Armstrong, Ulysses Livingston, Wellman Brand, O’Neil Spencer. Having money, not having money. Whatevs.

– Victoria Spivvey, who will pwn you. With a brilliant band. Henry Red Allen. And singing a song about getting dirty that feels as though it’s a song about getting dirty.

6

Modern bands, heavy on the high energy fun (after Klein):

– Janet Klein on ukelele, defusing things with the usually-hot ‘Sugar in my bowl’

– Midnight Serenaders. Favourite modern band. Guitarist used to be in Helmet. Yes. Light, bouncing band of fun.

– Old Joe’s Hitting the Jug, not the version we know by Stuff Smith (which features in this clip of Bethany and Stephan, my current favourite lindy hopping couple), a version by Danny Glass’s band of brilliance.

– Bob Hunt. Ellington win. This song is excellently exciting fun.

– Les Red Hot Reedwarmers French. From France. Doing wonderful Jimmie Noone wonderfulness. Exciting!

7

– SQUEEEE Rufus Wainwright Stairway to Paradise. Earworm. Camp. Wonderment. Listening at home, I love to follow this song up with Wainwright doing Cohen, fucking up your gender binaries.

– Terra Hazelton, with a band of OMG GOOD. Singing a silly song with lots of innuendo, written by Cole Porter, who was queer as fuck, so a lovely campy follow up to Wainwright. Vince Giordano plays on this version, and his band was also in the Aviator, where I found the Wainwright song.

– More Midnight Serenaders. I love the first line the most. Male vocals. Lovely. I like comparing this to the Julia Lee version.

– The male singer in the Hot Club of Cowtown has a gorgeously sexy style. I always think of him when I listen to that version of ‘Some of these Days’. I like the HCC a lot. I like this western swing treatment of a hot jazz favourite. This band featured the bass player from Casey McGill’s band.

– Of course I had to follow up with Bob Wills, western swing king. The HCC have a new album out which is all Bob Wills songs. I really love this song ‘Stay a Little Longer’, and this is a great version. But this is a better version.

8

– a band I know nothing about, doing a GREAT version of a song I love, ‘Chimes at the meeting’ by Willie Bryant’s band. Teddie Wilson played with Willie Bryant’s band. Sister Pork Chop. This is a rowdy, fiddle-heavy song that connects nicely to the HCC and Bob Wills.

– Firecracker Jazz Band, who are. This is a top fun version of a very common, famous song. The trumpeter Je Widenhousei was/is in the Squirrel Nut Zippers. Anyway, Katherine Whalen (of the Zippers) reminds me, vocally, of Tamar Korn.

– The Cangelosi Cards (featuring Tamar Korn) do a version of ‘Puttin’ on the Ritz’, but I think this rowdy live version is better. It features Gordon Webster on piano, and Jesse Selengut. This song is long and I’ve never played it for dancers. It is really really good.

– the vocals of this next song are interesting, and are a nice link to Korn’s interesting vocal style. ‘Better Off Dead’ is kind of of a tongue-in-cheekly-miserable song about being in a shitty relationship.

9

Australian content! Modern bands! Necrophilia! Darkness!

– Chris Tanner’s Virus. Continuing the theme of rubbish relationships. What a terrible friend.

– C W Stoneking. More awful relationships. Stoneking’s album featured some of the Virus people. They are all Melbourne folk. I love this song, but I don’t play it for dancers. I love the misery of it. See those Virus/Melbourne/Stoneking band people in Stoneking’s video for ‘Jungle Blues’ which has good misery too.

– Firecracker Jazz Band again! Not Australian. A song that feels dark, but gets a bit lighter. This is good dancing fun.

– ‘That Too Do’ is another Moten song featuring Basie, but also Jimmie Rushing. It also feels a bit dark and unhappy, but it a kind of winking-at-the-audience way.

10

silly, older songs, with vocals:

– Moten leads me to Noone. Noone. I love him. This is a brilliant little song. Is it about sex? Is it about being awesome? I’m too clueless to know. This is fun.

– Best version of ‘Truckin’. Back to Henry Red Allen. I really like it for the laconic, really laid back lyrics. They’re singing about a dance craze with very little vocal enthusiasm.

– ‘Murder in the Moonlight’ is silly. Feels like the Mound City Blue Blowers, has some of the same musicians.

Smaller bands, smelling of New Orleans:

– Then Bill Coleman, recording in France, with Oscar Aleman (not Django!). Remember those other French songs?

– Louis Armstrong and his Savoy Ballroom Five. This is hot. Hot. Hot. And this band features Zutty Singleton, Don Redman, of course, and Alex Hill, who was in the Jimmie Noone band.

– a version of ‘Blues My Naughty Sweety Gave to Me’. But by Wilbur de Paris and his Rampart Street Ramblers. It says ‘New Orleans’ to me, and that’s Louis Armstrong. de Paris was in Armstrong’s band, Jelly Roll’s band AND Ellington’s band. He’s glue. This is a good transcript version of a favourite.

– another version of ‘St Louis Blues’. By Bechet. New Orleans, yes.

11

Slower, blues dancing music:

Australian content!

…not really. Here’s what I said about this song in the Yehoodi show:

Well, this next song isn’t by an Australian musician, it’s by Louis Armstrong and his small group, including Velma Middleton, but Louis Armstrong is kind of an interesting example because Louis Armstrong Australia in about the mid-fifties, and between about 1928 and some date in the 50s, black musicians were banned from touring in Australia. And this was partly because Australia was a pretty racist place at the time, and there were fears that black musicians were bringing drugs and sex and misbehaviour to the innocent white folk of Australia. But in actual fact, it was probably more to do with pressures from the local musicians’ union, who didn’t want all these badarse musicians coming from the States and taking all their gigs.

I explore this topic in this post.

– Carol Ralph. Australian. Reminds me of Velma Middleton, from Armstrong’s small groups.

– Di Anne Price. You better help your new woman (get out of town). This is the sort of sentiment I like in my blues dancing music. More hi-fi, modern music.

– Koko Taylor. A little more soul. Assertive, sexually confident. Perhaps a little cranky.

– Sweet Home Chicago. Geetar. A natural progression from the feel of Taylor’s song.

Slower, dirtier male vocal blues:

– George Smith. Harmonica and guitar.

– Lonnie Johnson singing Evil Woman, a song women usually sing. I like the line about being too evil to sleep straight in her bed. I chose this version for the way it links up the the male vocals and sparse piano sound of the next song.

– Walter Brown (excellent voice!). Male vocal blues. More upsetting women.

– Cow Cow Davenport singing a brilliant song. All innuendo.

– Lionel Hampton’s band doing an uncharacteristically slow and mellow number. I like the feel of this one.

12

More blues. Serious. Groovier:

– Martha Davis, doing a wonderfully velvety song about ‘working’ for a man. A sparser style, which links us from the previous song quite well.

– …which sets us up nicely for Billie Holiday’s quite intense, but equally velvety classic live performance. You can see her singing it in this clip.

– Ella singing ‘Rocks in My bed’. I never find her all that convincing when she sings sadder songs – she always sounds like she’s smiling. This recording is interesting because it features Stuff Smith. It’s also really nice and slow and rocking.

13

– A song by Louis Armstrong with a band including Oscar Peterson from an album called ‘Ella and Louis Again’. Feels just like the Ella song. I’m not usually a fan of Armstrong singing, but sometimes he gets it just right. I like the way he lightens things up a bit.

Slightly faster, groovier, velvety stuff:

– Cecil McLorin Salvant, a very young French singer doing a sort-of-Billie-Holiday type performance. She has really cool delivery.

– I love this version of ‘Sweet Lorraine’, a song I love a lot. I like the way it’s often sung by women, and is a love song for a woman. This song is a bit older, and it’s a nice segue to a slightly earlier feel.

– And, finally, Duke Ellington’s band with vocals, doing a song I regularly use to shift gears while DJing, from chillaxed groovy back to chunkier old school.