Helen has asked for specific details about the tuning of Tharpe’s guitar in her comment here. Below is a big fat quote from an article called ‘From Spirituals to Swing: Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Gospel Crossover’ by Gayle Wald (published in ‘American Quarterly’, vol 55, no.3 September 2003), pgs 389-399. This is where I read that note about Tharpe’s tuning – hope it’s useful, Helen.

Wald’s article is mostly about Tharpe’s movement from black gospel music to the white jazz/blues/pop mainstream. Tharpe is taken as an example illustrating wider points about culture and music during this period. It’s a really interesting read.

Although Tharpe arrived in New York already highly credentialed in Pentecostal terms, Sammy Price, Decca’s house pianist and recording supervisor at the time Tharpe recorded “Rock Me,” apparently wasn’t feeling any of this joy. Tharpe, he recalled in his 1990 autobiography, “tuned her guitar funny and sang in the wrong key.” In all likelihood Price was referring to Tharpe’s use of vestapol (sometimes called ‘open D’) tuning popular among blues musicians in the Mississippi Delta region. (Muddy Waters is among the many blues guitarists, for example, who learned vestapol technique in the 1930s, when he was growing up in Clarksdale, Mississippi.) As common as it was in the South, however, vestapol tuning could sound distinctly crude and out-of-place in the context of northern jazz bands. By his own account, Price, who later went on to record several hits with Tharpe, refused to play with her until she used a capo, the bar that sits across the fingerboard and changes the pitch of the instrument. “With a capo on the fret,” he explained, “it would be a better key to play along with, a normal jazz key.”

Price’s brief story of the carpo as a normalizing technology is rich with implications for the discussion of what ‘crossing over’ to the realm of popular entertainment might have meant for Tharpe. Resonant of southern black communities and of musicians who honed their craft in churches as well as on back porches – musicians Hammond quite unself-consciously called ‘unlettered’ – Tharpe’s ‘funny’ guitar playing introduced, to Price’s ear, an apparently unassimilable element into the prevailing sounds of urban jazz. It’s also possible that Price was demanding that Tharpe sing at a higher pitch, to conform with popular as well as commercial expectations that high pitch evidences a correspondingly ‘higher’ degree of femininity. In any case, and as Price suggests, Tharpe quite literally had to adjust her guitar and singing techniques to make commercially popular, ‘secular’ records that would earn her an audience beyond the relatively small market of consumers of ‘religious music.’ The ‘makeover’ of Tharpe’s sound also has important gender and class implications less obvious from Price’s comment. In bringing her sound more into line with the sounds of commercial jazz, Tharpe would not only have to change her tuning, but ‘change her tune’ as far as her performance of femininity was concerned.

The ‘Hammond’ referred to in the article is John Hammond, an important figure in the promotion and management of a number of big jazz musicians. Gunther Schuller’s book ‘The Swing Era’ reads almost as a history of Hammond’s career. I think it’s important to note that this one white man was important for his influence on the developing jazz and swing music industry. His selection and then promotion of specific artists shaped the recording industry, popular tastes and the white mainstream’s understanding of and access to black music during this period. As the race records and black-run radio stations were forced out of the industry by white competitors and blatantly racist media regulation, black artists had less and less control of their own representation in mass media, and black musical culture was mediated by white corporate and cultural interests.

All of this makes for fabulous, fascinating reading. It is, though, all about America. I’m not sure how much (if any of it) can be translated to the Australian context. But that would make for interesting research in itself, particularly when you keep in mind that jazz in Australia is necessarily the product of cultural transmission – black music filtered through mainstream American recording and sheet music industries to white mainstream audiences and musicians and white Australian musicians and audiences. Sure, there were musicians making jazz in Australia (people like Graeme Bell of course), but I’ve been thinking about ‘authenticity’ and jazz in such a transplanted context… particularly as I’ve read recently somewhere (goddess knows where – I’d have to retrace my steps) that music tends to reflect the vocal patterns and intonations and rhythms of the culture in which it develops. So, we could draw from this the conclusion that we Australians would play jazz with an Australian accent. It wouldn’t sound like American – or black American – jazz. I’m hesitant to make comments about the relative value of localised jazz, but it’s an issue hanging in the background there…

But back to Hammond. John Hammond of course organised the concert ‘From Spirituals to swing’ at Carnegie Hall in New York in 1938 (you can see the artists here, in a recording of the concert) . This concert featured a bunch of super big artists (Jimmy Rusher, Joe Turner, Mitchell’s Christian Singers, Albert Ammons, Sidney Bechet, Count Basie, Benny Goodman). It’s goal was a combination of musical ‘education’ for the white mainstream and – indubitably, considering Hammond’s impressive business sense – promotion of black music to new white audiences/consumers.

I’m interested in this concert and in Tharpe’s cross-promotion to the mainstream as an example of cultural transmission – I’m fascinated by the way music and dance move between cultures. I’m also really interested in the uses of power in this process. Is it appropration? Stealing? Poaching? To quote (ad nauseum), Hazzard Gordon, we have to ask “who has the power to steal from whom?” when we’re looking at this process.

I”ve been writing about the way different cultures not only ‘take’ dance steps or songs from other cultures or traditions, but also the way they then adapt these ‘found’ texts to suit their own cultural/social needs, values, etc.

I’ve argued all through my work that we can see the social heirarchy of the US in the reworking of dances and songs. What did they need to do to make these texts palatable for white audiences? With Tharpe it was ‘retuning’ her guitar and voice. With lindy hop, it was ‘desexualising’ and ‘tidying’ up the basic steps. Or at least presenting a different type of sexual performance.

Some interesting references

There’s a really great page discussing race records that includes audio files, images and written text here on the NPR site.

There’s also a pbs (US) site attached to the Ken Burns Jazz doco discussing race records.

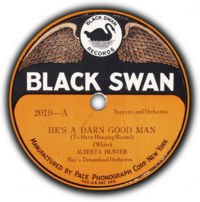

For a (very nice) academic discussion, see David Suisman’s article called ‘Co-workers in the kingdom of culture: Black Swan Records and the political economy of African American music’ (The Journal of American History vol 90, no.4, March 2004, p 1295-1324) which discusses the ‘race records’ of the period and the racialised nature of the American recording industry.

You can also walk through this article via the JAH’s fantastic site (complete with images, sound files and other wonderful things). This is one site that really ROCKS.

Derek W. Vaillant has written a really interesting article about black radio in Chicago in the 20s and 30s which discusses these issues in greater detail (‘Sounds of Whiteness: Local radio, racial formation and public culture in Chicago 1921-1935’, American Quarterly vol 54 no. 1, March 2002 p25-66).

Katrina Hazzard Gordon has written quite a bit about African American dance culture. Here are a couple of references:

Hazzard-Gordon, Katrina. “African-American Vernacular Dance: Core Culture and Meaning Operatives.” Journal of Black Studies 15.4 (1985): 427-45.

—. Jookin’: The Rise of Social Dance Formations in African-American Culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990.

Read more about John Hammond, look at photos and listen to music here on this Jerry Jazz Musician page.

Wald, Gayle. “From Spirituals to Swing: Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Gospel Crossover” American Quarterly vol 55, no.3 (September 2003): 389-399.

Great post dogpossum.

Re Sammy Price’s comments on Tharpe’s guitar tuning. Anyone playing strictly open D would have a hard time in a jazz band. I’d say there is a good musical reason to use a capo to follow the key changes often found in such bands.

A quick listen to Sister Rosetta Tharp Vol 3 on Document (which I think has Sammy Price in piano) gives me at least a song in C and one in Eb.

Open G, another favoured delta tuning, would have the same limitation. The Hawaiian great, Sol Hoopii overcame the limitations (as open G is the main Hawaiian tuning) of regular open tuning by developing a C# minor tuning to satisfy his jazz leanings.

On your idea of cultural transmission, an interesting phenomena was the insistence on authenticity that accompanied the blues explosion back in the mid-1960s. The music of Son House, Skip James, Bukka White etc was not watered down for the white audience. It was raw authentic expressions of the blues. Except for the white audiences who forgot that blues was a dance music – they would respectfully sit still to the rediscovered great. Quite a change from the audience at juke joints.

This ‘insistence on authenticity’ re 1960s blues is very interesting, Shaun. There’s much the same sentiment in swing dancers’ attention to recreating ‘original’ swing dances from the 20s/30s/40s. It’s also something which I’ve found a bit problematic, at least in regards to swing dancers. Here there’s a community of young people who are largely representative of the elite or at least socially powerful sections of a community seeking to ‘recreate’ the vernacular dances of African Americans. And these are largely white, middle class young people in Australia – Singapore, Japan and Korea offer really interesting contrasts. Still the ‘elite’ or at least socially powerful, just different ethnicity – but representative of powerful members of _their_ community/society.

There’s been a great deal written about the white mainstream’s appropriation of black dance and music culture – from jazz to hip hop. I find it useful to remember Hazzard Gordon and ask myself ‘who has the power to steal from whom?’ What does it mean if it’s a powerful group ‘reviving’ a dance from a socially disempowered group, distanced by time and geography and culture? Is it a restatement and reinforcement of power relations and social difference?

I use Jane Desmond’s work in discussing a ‘dialectics of cultural transmission’, where I discuss this transmission of cultural forms as being representative of social relations. And also allowing for a range of meanings and interpretations. So it is not always stealing or always appropriation.

I also take dance as a public sphere and then ask ‘who is contributing to this public sphere? Which voices are most authoritative?’ Nancy Fraser argues that diverse public discourse not only allows all of us access to public talk, but also allows us to discuss all matters of interest to each of us, and ultimately allows us all to contribute and participate in our own ‘language.’ In that scenario, Fraser would see Tharpe’s retuning as a demonstration of restrictions on her participation in public discourse – she couldn’t sing or talk in her ‘own language’.

Having said all that, my main concern with dancers is that they don’t interrogate the historical contexts of the dances they’re reviving. Indeed, setting out to ‘revive’ a dance assumes that it is already dead. And that declaration is a demonstration of power in itself, as no vernacular dance dies and disappears ultimately – it changes form and is present in new dances which have adapted its basic structures or rhythms or aesthetics. So when white dancers say ‘I am researching and reviving authentic jazz dances’ and then set about re-presenting and performing them using their white bodies and white ways of moving and white social power privilege, they are effectively ‘speaking for’ those past dancers. There are additional problems with the sources swing dancers use – the film industry of the day was inflected with economic and social factors that decided who could and couldn’t appear on-screen, how they would be shot and should perform, and whether or not they were credited for choreography or performance.

But, speaking as a dancer, and as someone who takes great delight in seeing people actually getting out there and having a bash at these olden days dances, I don’t want to dismiss a revivalist project out of hand as doomed and patriarchal and capitalist and indelibly wrong. There’s no reason why we can’t take up the resistant themes of black dance and make them live again – use them for transgressive or resistant purposes. I just think that it’s important to maintain a sense of history and to articulate and remember the past and to be aware of the present social structures which allow some of us the time to actually set about reviving, and prevent some of us access to the dance floor at all.

Wow, muchas gracias Dogpossum, that is erudite indeed. The info in the third para will allow me to kick off a how-to enquiry via Google. If my experience with looking up the DADGAD tuning is anything to go by, there’s a wealth of info out there e.g. how to play the equivalent of this or that chord.

Now I just need to find the time now the skool holidays have finished and i’m back at work!

Quick comment re the capo I should have mentioned yesterday. I don’t have any of her music with today but using and open tuning, relied a lot on open string licks. A capo would easily allow her to use open strings in other keys.

dogpossum, I quite agree with the idea that whether a dancer or a musician, one should understand the historical context of the music they are trying to revive. Blues is a classic example. Copping Robert Johnson licks is one thing. But taking the time to understand where the music is coming from can prevent mistakes in musical incongruity down the line.

You know, on the other hand, there’s something to be said for ‘just dancing’ or ‘just playing’… I never know how I feel about this stuff. On the one hand I’m all right on with the politics. On the other hand, the part of me that’s actually dancer realises how those sorts of ideals aren’t always practical when you’re out there on the dance floor…

How do we negotiate these things, especially when we are (as I am) writing/dancing from a pretty privileged position?

I caught the last half hour of a show last Sunday that was about Australian blues music. Now the whole idea of Australian blues may seem to be very strange if viewed through politics. Yet, Matt Taylor from Aussie blues band Chain recounted the time they toured with blues legend Albert Collins. Albert told them that Chain were blues but not a blues he had ever heard.

It is an interesting comment. But you’re right that there are time when it is best to shut up and just play/dance.

Australian blues… I remember hearing a Jimmy Little version of a blues song called ‘Cottonfields’ that really seemed appropriate to me. It was certainly a really nice song (it’s here: http://www.abc.net.au/dig/stories/s1429301.htm ).

There’s an interesting quote from Little on the site:

“We are closely aligned with Mother Nature and Father Time in our customs and traditions and culture. So the music we relate to is country orientated, which we see as parallel to Blues and Jazz.”

The Blues and jazz is a deep expression from black Americans, Afro Americans. In our case there is some similarity, but there’s also a vast difference between our distant brothers and sisters abroad. The most obvious is that Afro Americans were taken to America. Indigenous Australians were already here, so we didn’t have that slave attitude of being possessed. We were more dispossessed.”

I’m interested in the distinction between being ‘posessed’ and being ‘dispossessed’.

–as an aside, I’ve just listened to this episode of Awaye (http://www.abc.net.au/rn/awaye/stories/2008/2099576.htmhttp://www.abc.net.au/rn/awaye/stories/2008/2099576.htm) which talks about Indigenous Australians’ experiences under the protectorate policies… sounds quite a bit like slavery to me.

We’re looking for decent blues bands for MLX again this year (probably just one, but perhaps two). Saying a ‘blues band’ is kind of unhelpful, though – I need to be more specific. It has to be good for dancing. Which is just as unhelpful a category.

…so if anyone knows of any really good Melbourne blues bands…

Must be sloooow (ie playing slow music) and ‘good for dancing’.