Appropriation, step-stealing, cultural transmission, imitation, impersonation, copying, poaching….

So my last chunky post ‘Historical Recreation’: Fat Suits, Blackface and Dance has kind of hit like a ton of bricks. Cultural transmission in dance – the movement of dance steps and forms and ideas between and within cultures – is pretty much my core research interest, and I definitely don’t want to leave this topic just yet. I certainly didn’t want to leave things with a fairly despairing discussion about blackface and discomforting appropriation.

This is a very long post, and it’s divided into these sections:

- 1. What is cultural transmission?

- 2. Power, class, identity and cultural transmission

- 3. Cultural transmission via Star Trek fans

- 4. Cultural transmission between generations

- 5. Improvisation, making stuff up and dance-as-discourse

- 6. Improvisation, making stuff up and ballet

- 7. Cultural transmission in dance as politics

- 8. Everyday life and cultural transmission in dance

- 9. Cultural transmission in modern day lindy hop

- 10. Historical recreationism, gender and having a clue

- 11. Being right on and doing historical recreationism: fan SQUEE

- 12. Putting it all into practice: an example

- 13. Dancing in drag

- 14. Eccentric dance: where I’d like to live

- 15. References

1. What is cultural transmission?

Right. What do I mean when I talk about ‘cultural transmission’. Basically, in this context, I’m talking about the movement of cultural ‘stuff’ – in this case dance steps/rhythms/styling/etc – between cultures. But why stop there? I like writing long posts, and this is such an exciting topic. So strap in.

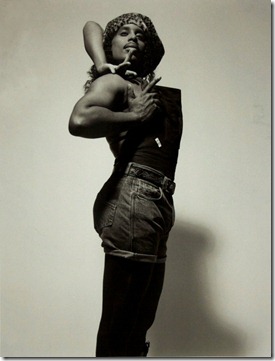

(photo of Willi Ninja stoled from here)

A fairly simple example of cultural transmission in dance would be the movement of vogueing from queer culture to mainstream pop culture via Madonna’s 2006 Vogue video clip. The 1990 documentary film Paris is Burning is a cool beginning place for looking at this stuff, and you can watch Part 1 of Paris is Burning on Youtube. You can see Will Ninja dancing in the Malcolm Mclaren Deep in Vogue music video.

Wait. I’ve just dated myself. Ok. So another cool example is the way Krumping was promoted in the mainstream by David LaChapelle’s 2005 film Rize. Fark. My cultural references – they are out of date! And I don’t want to suggest that just one film or music video is enough to stimulate the shift of a dance from marginal to mainstream spaces. There’s quite a bit more going on, and quite a few more people involved in the process, from dance teachers to performances by lesser-known dancers to trends in night club cultures and DJing interests.

Basically, we’re talking about dances moving from one cultural context (in these cases queer culture and urban African American youth street dance culture) to another (mainstream, predominantly white-owned and organised music industry). These two examples suggest that this cultural transmission thing is a matter of one rich, powerful culture ripping off another. Maybe. But cultural transmission is more complicated. Not every example of borrowing or step stealing is dodgy.

I often talk about the cake walk as an example of cultural transmission, and I’ve listed a bunch of references for my ideas about cake walk in Dance competitions and policing public space. In this case, slaves borrowed particular movements from the culture of the slave owners. And then fucked with it. This is a bit more transgressive than Madonna having some kids vogue in her video clip.

Power, class, identity and cultural transmission

But I do think we need to keep Katrina Hazzard Gordon’s words in mind: “Who has the power to steal from whom?” What are the broader power relationships at work in the society where this transmission is happening? Who has the most money? Whose opinions and beliefs are most frequently presented in the media? Which types of sexual relationships are presented as ‘normal’? Yes, it is possible for less powerful people to steal dance steps from other groups, but what does it mean when they do?

If we’re going to do informed thinking about this, we have to recognise that societies and relationships are structured by class, by gender, by sexuality, by age, by ethnicity and so on. The choices we can (and are allowed to) make, the way we dance, is affected by who we are, as social beings. If you totally believe that none of this matters, and that the individual is simply who they have made themselves, then this is not the post (nor the blog) for you. I’m not saying that we are powerless to change our fates, but I am saying that it is naive to assume that we are just the sum of biology or individual choices. Social animals, yo.

In my work I’ve argued that cultural transmission involves some sort of ideological and structural reworking for the thing or practice being transmitted. Dance steps aren’t just carried, whole, to new cultural locations and traditions. They get changed a bit. They’re usually toned down for conservative mainstream audiences. There’s quite a bit written about this, stacks talking about hip hop, but quite a bit on partner dancing. For example, Jane Desmond talks about mambo and its popularity in white communities in the 1950s, and Sheenagh Pietrobruno discusses salsa classes in Montreal. But this repackaging of marginalised practice for mainstream consumption isn’t restricted to dance. Rosetta Tharpe’s guitar playing was retuned for white audiences. The recent remake of Hairspray pretty much undid all the badass subversion of the John Waters original – folks got whiter, language got cleaner, dances go duller, drag queens got undragged.

It’d be easy to just give up, to dismiss cultural transmission as indelibly marked by class and power and ethnicity and the work of The Man. But then, you’d be giving up before you got to the good part. Yes, the commodification of dances like mambo and lindy hop can be read as the appropriation of street dance by elite groups in the mainstream. But cultural transmission doesn’t work in only one direction. We hoomans, we’re complicated beasts. And terribly creative. Cultural transmission can be subversive and exciting.

Cultural transmission via Star Trek fans

I developed my ideas about step stealing and cultural transmission by way of fan studies. Or, more specifically, by way of textual poaching, Camille Bacon Smith and women SF fans. Women who wrote slash fiction. The idea here, is that fans of the Star Trek television show imagined whole new lives for the heroes, Captain Kirk and Mr Spock. Whole new relationships. In the tv show Spock and Kirk are platonic friends. Very good friends. But in the imaginations of fans, they could be so much more.

I really like this idea that characters in a story have entire lives we don’t see. I also really like the thought of fans – people who are painted as helpless consumers – totally fucking up the myth that they are victims of aggressive television. Basically, I took this idea of textual poaching (where fans ‘poached’ characters or stories from mainstream media texts) and applied it to dance. Thing is, I wasn’t the first person to get up on this idea. Frankie Manning himself had a reputation as a hardcore step stealer. Someone who’d copy your steps, then pull them out himself. Of course, the trick lies not in creating an exact copy of that original step, but in remaking it and performing it a new and unique way that makes people SQUEE. And Frankie certainly made people SQUEE. Nor was he first at this. It’s a feature of vernacular dance generally.

Cultural transmission between generations

I’m also very interested in the transmission of dance steps and forms across generations. It stands to reason that young people gonna do young people things, and there are types of dances which they’ll invent to suit their needs and interests. Lindy hoppers totally understand this. We regularly tell each other stories about how the swingout was an adaptation of the European partner dance format. Or, to be clearer, there’s a story about how Shorty George Snowden and his partner broke out into open during a dance contest, and totally blew people’s brains. And of course, there’s also the story about how Frankie Manning and Freda Washington, keen to bring something new to win a dance competition pulled out the first air step and blew people’s brains with that.

Vernacular dance happens in cross-generational spaces, from homes to street parties and church dances. There’s quite a bit written about this: Katrina Hazzard Gordon has a book called Jookin’, LeeEllen Friedland talks about this in reference to tap dance and hip hop. As a result, dance forms do not simply die out or disappear when the current generation moves on to something else. ‘Old’ dances live on in the dancing bodies of older people in the community, and are regularly revisited and ‘borrowed’ by younger people.

Jonathan David Jackson argues that black movement traditions are ‘choreologically contemporaneous’. That’s another way of saying that new dance steps and styles (like lindy hop in the 20s/30s, breakdance in the 70s/80s) develop at the same time as old fashioned steps stop being popular with young people. Jackson argues that rather than disappearing, replaced by new steps, old steps are recycled.

principles of physical, spatial, aural, and qualitative action are passed on from one tradition to the next (41).

This is pretty exciting stuff. It means that lindy hop didn’t die out in the 1950s. It just changed shape. This also means that older dances are continually revived and rediscovered by younger people. How? By watching old folks dance, by learning from old folks. But also by the fact that principles of movement (balance, spatial awareness, everyday rhythmic movement) persist in a community. They don’t just disappear.

I really like this cross-generational aspect as it encourages a relationship between young people and older people which is based on mutual respect, and cements the role of older people in our community. I once gave a talk at a conference on cultural transmission in dance where there were some young Indigenous Australian dancers from Bangarra in the audience. I ended up talking about this idea of learning dance from elders with a young koori woman choreographer. We were both excited about the idea that our dance cultures were so community-rooted, but we each also had frustrations about how this could limit what we did as women dancers. In her case, there are some warrior dances which women aren’t allowed to learn, but which she found particular exciting and inspiring. So there are limitations to this cross-generational stuff as well.

Improvisation, making stuff up and dance-as-discourse

Yet this cross-generational ‘choreography’ also implies and responds to social change within the community and wider society. Lindy hop was a response to the development of swinging jazz and the rise of the Harlem renaissance: new music demanded new dance steps. Jazz, at its most fundamental level, combines improvisation with formal structure. For me, this is the most exciting part. Jazz music is vernacular music (or it was – I’ve been meaning to write about jazz’s shift from folk or pop music to ‘art’ music). Jazz is also all about improvisation – making stuff up. Innovating. Changing. Being flexible enough to bend and respond to the user’s needs and ideas. So jazz dance has to be the same way. It’s all about innovation, improvisation, change, response.

Improvisation, making stuff up and ballet

So, if innovation and change are essential parts of vernacular dance, what about concert dances like ballet? I’d argue that they’re all about managing change and in many cases restricting it, preserving dances as they are. But even there, choreographers and dancers are innovating. And it’s certainly true that vernacular dance is also carefully managed. There are, for example, some dances you wouldn’t do in front of your parents. Frankie Manning used to tell a story about his mother going out to dance in a way that she didn’t think was appropriate for a young boy to see (let alone do). This is an example of how dance at once reflects cultural and social mores, but is also regulated and managed by community values. Just like ballet, only it’s done in a different way.

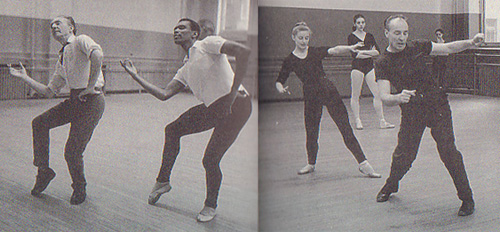

George Balanchine is a good example of a ballet dancer and choreographer who brought African American movements and aesthetics to ballet, pushing some barriers (not without challenges) and introducing new ideas to a fairly resistant culture.

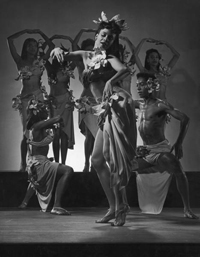

(Katherine Dunham, 1943 Life Collection)

Katherine Dunham was a dancer and choreographer who did similar work, stretching concert dance with movements and shapes and ideas from other cultures. In this case, we can see clearly politicised goals at work – Dunham was making it clear that ballet and ‘elite’ white mainstream art dance was enriched by contributions from other dances and other dance cultures.

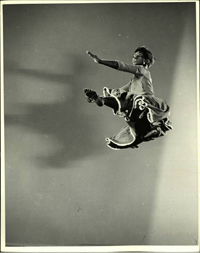

(1939 image also from the Life collection)

Pearl Primus is another example of a black woman dancer moving into ballet/concert dance and bringing with her quite radical ideas about movements and types of movement.

Cultural transmission in dance as politics

These are all examples of ethnicity and concert dance as a place for cultural transmission. I talked a bit about the specific changes and differences between these different dance traditions in gimme de kneebone bent. I’m really excited by the idea of dance as a product of culture as well as physiology. Our sense of aesthetics in dance is informed not only by our cultural values and who we are, as social beings, but also by our ideas about gender and beauty and art generally. This is partly why I get so worked up about shoes. High heel shoes make feet seem smaller and pointed, and the leg seem longer and straighter. Legs in heels aren’t some sort of objective marker of ‘beauty’. Feeling that legs in heels is ‘sexier’, ‘more feminine’, ‘better’ than legs in other shoes is a product of how we are raised, of social/economic class, the culture we live in, and how we think about bodies and beauty. And not everyone shares these ideas. I simply think it’s a mistake to box ourselves in with limited ideas about what can be beautiful or skilled dancing. We are capable of such wonderful things; why limit ourselves to just one small corner of that?

So change (often through individual improvisation and innovation), is a necessary feature of vernacular dance. Re-presenting everyday life in dance lets dancers express themselves, and engage with the ideas and powers of their local community and wider society. This become especially important when the dancers involved do not have access to the ‘official public sphere’ – to newspapers, films, mainstream media, public lectures, the education system and so on. Dance can give disempowered folk a chance to recreate gain ‘control’ of their often hostile everyday life.

Everyday life and cultural transmission in dance

Vernacular dance – street dance, folk dance, rather than concert or stage dance – are responses to people’s everyday lives and environments. So you see types of movements in vernacular dance which echo the dancer’s everyday movement and lifestyle. LeeEllen Friedland talks about rhythmic movement in day to day life, arguing that when you live in a culture where music and dance are part of everyday life, there’s no clear line between ‘dance’ and ‘rhythmic movement’. So, for example, the basic charleston step which we lindy hoppers are nuts about, is structurally very like walking. The arms swing, the legs move forwards and back, the bounce which generates energy in the movement originates in the torso (or core) travels out through the body, to the arms and hands. Just like when you walk. More specifically, there are plenty of jazz steps which are deliberate references to everyday activities and movements. For example the ‘cherry picker’ (or I’ve heard it called ‘praise allah’) looks just like reaching up to pick cherries, then down to put them in a basket.

One of the things I’ve especially liked is the thought of dancers imitating real live people in their neighbourhoods. Or ‘types’ of people. The pimps in Harlem. Sailors on the docks. Plantation owners. For a people without access to the mainstream media, dance offers a right of reply, a discursive space for the thrashing out of ideas, the resolution of conflict, the management of public identities and social norms.

What all this then means is that dance becomes an extension of everyday life, rather than a discrete, separate activity.

Cultural transmission in modern day lindy hop

That’s pretty much what my research was about. Except I then went on to talk about what happens in modern day lindy hop contexts. Because I was grounded in media and cultural studies, I was particularly interested in how dancers today use digital media to do all this. I talked about digital video clips and learning dance steps and sharing dance ideas cross-culturally. I also talked about online talk and developing and cementing international and inter-scene relationships via online talk. And I talked about DJing using digital tools.

Ok, so let’s go there. Let’s talk about modern day lindy hop and cultural transmission. If we can agree that black American dancers imitating and step stealing and poaching is empowering and subversive, what does it mean when modern day dancers start doing this stuff? I think it can be highly problematic (as I described in ‘Historical Recreation’: Fat Suits, Blackface and Dance. But we can’t stop there. What about Korea? What about Japan and Singapore? What about black American dancers today learning lindy hop? What about Asian-Australian dancers imitating Dean Collins? Shit is wacked, right? I mean, we can’t just write off the modern lindy hop project as fucked up appropriation or racism. For every blackface performance there’s stuff like this:

This is, of course, a group of Korean lindy hoppers making a birthday greeting for Frankie Manning, combining traditional Korean song and dance with the shim sham. It’s the ultimate mark of respect for an older man, a teacher, and a hero for these young Korean people. It’s also a brilliant example of cultural transmission, combining all sorts of musical and dancing influences. I think Frankie would have adored it. I know I do. It makes me tear up with its sincere respect and affection for Frankie Manning.

And we have to think about the Two cousins video clip. Neither of the men in that clip are African American, but they are of African descent, and they are thoroughly grounded in the history of this dance, both creatively and politically. I remember Ryan François talking about how important it was a young black British man to discover lindy hop and Frankie Manning. This recreationism can be suspect, but it can also be wonderful and empowering and exciting.

I’ve talked a lot about race and ethnicity here. But let’s talk about gender and sexuality.

Historical recreationism, gender and having a clue

I have some reservations about a hardcore historical recreationist approach to lindy hop today. Mostly because, hey, we don’t live in the 1920s, 30s or 40s. Yes, the costumes and the music and the dances are fun. Super fun. And it’s totally ok to spend lots of time and effort into recreating them. But the 1920s, 30s and 40s weren’t terribly awesome places to live. Particularly if you weren’t white. It was even a bit shit if you were a woman. I mean, I like the right to vote, to own property, to divorce. I like having clean water and food, and good solid health care. I like knowing my child won’t die from polio or that I won’t die from a botched abortion on a kitchen table because I didn’t have access to safe contraception. And I’m a white woman. If I’d been black, in America or Australia, things would have been way shitter.

I don’t want to recreate those days. I don’t want to pretend that they were so wonderful and great. And I think that if you’re going to get into historical recreationism, you need to be very aware of your own privilege and power, and of the broader historical contexts of the clothes and music and dances you love. I mean, a Pearl Harbour dance, today? Not so cool. Blackface? Again, you gotta have a think about what that meant at the time, and what it means now. This is why I’m really not ok with WWII themed dances. I’m not at all ok with planning a dance – a good party time – based on the idea of conflict that killed so many and to which my own grandparents were so seriously opposed. Sure, I think we should remember these conflicts, but I also think we should think about those wars and the meanings behind the symbolism we just mash into our dance events.

Being right on and doing historical recreationism: fan SQUEE

Ok, so how do I reconcile all those misgivings with my absolute passion for the dances and music of the period? How do I do recreationism without giving myself the shits? Firstly, I go for the intent and the ideas behind and within these dances. Lindy hop, jazz dance, vernacular dance can be so subversive. Think of that cake walk, the mocking of slave owners, the thumbing of the nose to the oppressor. That’s an excellent idea. Think about impersonation and derision dance – speaking back, responding to bullshit politics on the dance floor. This is exciting for me because it is non-violent, creative activism. But it can also just be plain good fun. I mean, it blows my BRAIN that leading in lindy hop can at once be so incredibly subversive (a woman making decisions? a woman, complete without a man? unpossible!), but is also (and more importantly) so much FUN.

I’ve always thought that while getting angry about injustice is useful for galvanising the self, it’s also bloody depressing. Eventually, I need to get active and to empower myself. And I see being physically strong and capable (to the best of my ability), being creative, finding pleasure in my self and my own body as the most exciting way of fucking over the patriarchy. I mean, the sweetest, finest revenge is simply being happy and confident. Particularly in my culture, where the ‘beauty industry’ is all about trying to make me anxious and self-doubting. I choose not to waste my time and worry on what my hair looks like or whether I’m pleasing some man. I choose to spend my worry and time on getting that goddamn swingout as fine as it can possibly be.

The fact that we can do all this in public is also pretty damn good. Dance is a public discourse. It’s an engagement with ideas and social forces and structures. It’s a way of expressing our own ideas. Our own selves. That is why I’m so keen on the idea of diversity in dance, and in not enforcing a particular way of dancing as a woman or a man. We are all the more richer for our differences.

Putting it all into practice: an example

So let me sum up with a nice example. I’m going to talk about Dax & Sarah – Moses Supposes US Open Cabaret 2010 performance:

Which is a recreation of Gene Kelly & Donald O’Connor in the ‘Moses Supposes’ number from the 1952 film Singing in the Rain

What do I find so great about this? First, it’s great dancing. I like what I see. It’s historical recreationism to the nth degree. These are two modern day dancers performing choreography inspired by a particular film sequence, wearing costumes inspired by that same sequence, using the sound from that sequence. SQUEE! But unlike the Day At the Races routine, we’re not seeing any dodgy fatsuits. Race is still happening here – these are two white kids performing a routine danced by two white man. Whiteness is race, is ethnicity. I think class is also at work (and a central theme for the original routine, of course). But the gender stuff is what I get most squee about.

I really really like it that Sarah has co-opted the part of a male actor and dancer. So many of the solo jazz routines danced by women around the lindy hop world have them in some sort of sexeh frock, doing teh sexeh ladee dancing. But in this case, Sarah is wearing trousers, a blouse (rather than a shirt), flat shoes, and her hair is tied up. She definitely reads as conventionally female, but not in a spangles-and-sex sort of way. More importantly, she’s dancing virtually the same steps as her male fellow performer. I especially like it that this performance works in complement to her existing ideas about shoes and whatnot. I think it’s particularly subversive that she can do all the gender stuff.

I’m quite keen on this idea of dancing in drag, or of performing gender in this way. I mean, I often think about my own dancing in this sort of way. I make extensive, and thorough, use of historical clips myself. I use them as a source for new steps, for ways of holding my body, for styling, for attitude. But I’m using both the male and female dancers for this. When I’m dancing, I frequently think to myself “I’m Frankie!” or “I’m Al!” or even “I’m Skye!” It’s not that I’m actually imagining I’m these men in particular, or a man in more general terms. I’m very happy with being a woman. And with femininity (just not that boringly conventional heteronormative ladygirl femininity). But sometimes, in those moments when I’m dancing, I can imagine that I’m occupying that space that is awesome dancing and freedom of movement and creativity that I associate with my male heroes and role models. I want to occupy that Al Minns Leon James attitude, that Frankie power and excitement, that Skye dancing-squee enthusiasm. It makes me feel confident and happy. I know I’ll never dance like them, nor do I really want to be just like them, but it can be important to me to put on that identity like a costume. So when I’m dancing, I’m wearing that attitude, and it gives me confidence. Also, playing dress up and make believe is bloody good fun.

So when I see Sarah in that clip, I think ‘Yep. That works for me.’ It’s a moment where the dressing up and recreation is super fun and exciting. I don’t have to negotiate dodgy race politics. I can just enjoy the subversion of a woman ‘dancing man’ but owning it in her way. I guess, though, that this is how hegemony and patriarchy work. The smooth fit of class and race seems ‘right’, and anything else is kind of jagged and unsettling. We’re used to seeing these sorts of images of healthy young white male bodies being athletic and creative, ‘speaking’ and articulating a clever commentary on social relationships. Not much is being challenged by the original sequence. Really, the best part is Sarah’s occupying the male character and reworking it to accommodate her own gender.

Eccentric dance: where I’d like to live

I think this is why I’m very interested in eccentric dances. I had this sudden moment about a year ago, when I was doing lots of solo work, when I suddenly thought, watching videos of myself “Why am I trying to be ‘beautiful’ or ‘cool’ or otherwise conventionally attractive or ok? These guys aren’t.” You know that moment when you first watch yourself dancing on video and you cringe? Well, I realised that I was trying to get rid of that feeling by conforming to the sorts of ‘cool’ dancing I saw in modern day comps. I gradually realised that it wasn’t really possible for me to look like that. I’m not tall and thin; I’m kind of square with some round parts. I’m not hugely athletic. I have a round belly and lots of jelly all over me. I have big slabs of muscle in my legs and arse, and my arms don’t quite get straight. I’d been thinking of these as problems to overcome. But then I decided that these could become my strengths. No one else is quite my shape, or moves quite my way. I don’t need to please the people watching me – I can make them uncomfortable. Or nervous. Or embarrassed. Or – goddess forbid! – make them laugh.

This is when I started getting serious about using archival footage for finding role models.

- Snake Hips Tucker: in the 1930 film Crazy House. It doesn’t seem possible to do what he does, but watch his hands – how does he contrast their light fluttering with the crazy stuff in his joints? Or the way he makes walking interesting in Love in the Rough in 1930. He was a frightening, aggressive, violent man who could do amazing, mesmerising things on stage that wouldn’t let you look away.

Al MinnsLeon James: does more with his face than with his body, but at the same time, his movements are so precise and so carefully planned, they make you watch every second.- James Barton: in 1929 film After Seben. There’s that moment at 2.08 when he stops to wipe his shoes, where it feels like he’s disrupting the flow of the routine, and doing something silly and inappropriate. How can I use that idea of disrupting narrative ‘flow’? And he’s a white man in blackface: how can I unravel that and make it tenable? Is it even possible?

- And my latest obsession, James Berry in Spirit Moves. I like the way his movements are just so strange, especially compared with Sandra Gibson. In this film, I want to be Berry. I’ve seen sultry woman dancing a million times before. But how often do you get to see strange woman dancing?

There are heaps of other clips to reference, and lots of women dancers to reference as well. I really like eccentric dances, because they’re about finding your own way of using your own body to do your own stuff. I could get really into reproducing the stuff I see in films exactly. And I do. But ultimately, what I’m really trying to do is find my own flavah flave. I want to be utterly unique. I find inspiration in all sorts of dance clips, but I don’t want to be a carbon copy of something from ye olden days.

But this post has gone on long enough. To sum up, I want to say that cultural transmission is such a complicated thing. It’s inflected by all sorts of issues, and it’s just not very interesting or useful to dismiss it all as ‘appropriation’. There are ways of negotiating good stuff, here, and I’m not ready to let it go.

- Bacon-Smith, Camille. Enterprising Women: Television Fandom and the Creation of Popular Myth. Series in Contemporary Ethnography. Eds. Dan Rose and Paul Stoller. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992.

- Bacon-Smith, Camille. Science Fiction Culture. Feminist Cultural Studies, the Media and Political Culture. Eds. Mary Ellen Brown and Andrea Press. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000.

- Desmond, Jane C. “Embodying Difference: Issues in Dance and Cultural Studies.”

Cultural Critique (Winter 1993 – 94): 33 – 63. - Desmond, Jane C. ed. Meaning in Motion: New Cultural Studies of Dance. London: Duke University

Press, 1997. - Friedland, LeeEllen. “Social Commentary in African-American Movement Performance.” Human Action Signs in Cultural Context: The Visible and the Invisible in Movement and Dance. Ed. Brenda Farnell. London: Scarecrow Press, 1995. 136 – 57.

- Hazzard-Gordon, Katrina. “African-American Vernacular Dance: Core Culture and Meaning Operatives.” Journal of Black Studies 15.4 (1985): 427-45.

- Hazzard-Gordon, Katrina. Jookin’: The Rise of Social Dance Formations in African-American Culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990.

- Jackson, Jonathan David. “Improvisation in African-American Vernacular Dancing.”

Dance Research Journal 33.2 (2001/2002): 40 – 53. - Pietrobruno, Sheenagh. “Embodying Canadian Multiculturalism: The Case of Salsa Dancing in Montreal.” Revista Mexicana de Estudios Canadienses nueva época, número 3. (2002).