I think my favourite set was the last one, where I did band breaks for the Stockholm All Stars. I was feeling very tired, but also very relaxed and willing to try songs and combinations I never use. The room was super crowded and hot during band sets, but it emptied out during the breaks, except for a few hardcore dancers. I was trying to keep the music low-key, and not compete with the fun vibe of the band. Nothing hi-fi.

I was quite proud of the June Christy/Mildred Bailey transition. Both are really great bands, and the vocalists have brilliant timing.

I played quite a bit of Chick Webb this Herrang, and really leant on the big bands generally. I especially like that version of Tain’t What You Do because it’s so _good_ (Webb’s band is just GREAT), you see dancers consider shim shamming, then just give in and swing out. Because it’s the best. It was also fun to see dancers get into that Big Apple song (my current fave), and to try out ‘big apple’ steps and claps and things to it. You can see that I was working with a few female vocalists, which I don’t often do.

There was a lot of Basie played in camp this year, which I got a bit tired of, tbh, but I also started to really enjoy Lester Young’s weirdness, especially in the later years. I enjoyed adding in the ‘odder’ later stuff of artists like Slam Stewart, JC Heard, Buck Clayton, etc. You can see bop on the horizon, but it’s not here yet. My general rule with this sort of more ‘interesting’ swinging jazz is to not play it during the high energy/crazy parts of the party, and to not play it in beginner hour. Instead I play it in more contemplative parts of the night, when peeps are more relaxed, and there are more experienced or experimental dancers around. ie band breaks, late shifts, etc.

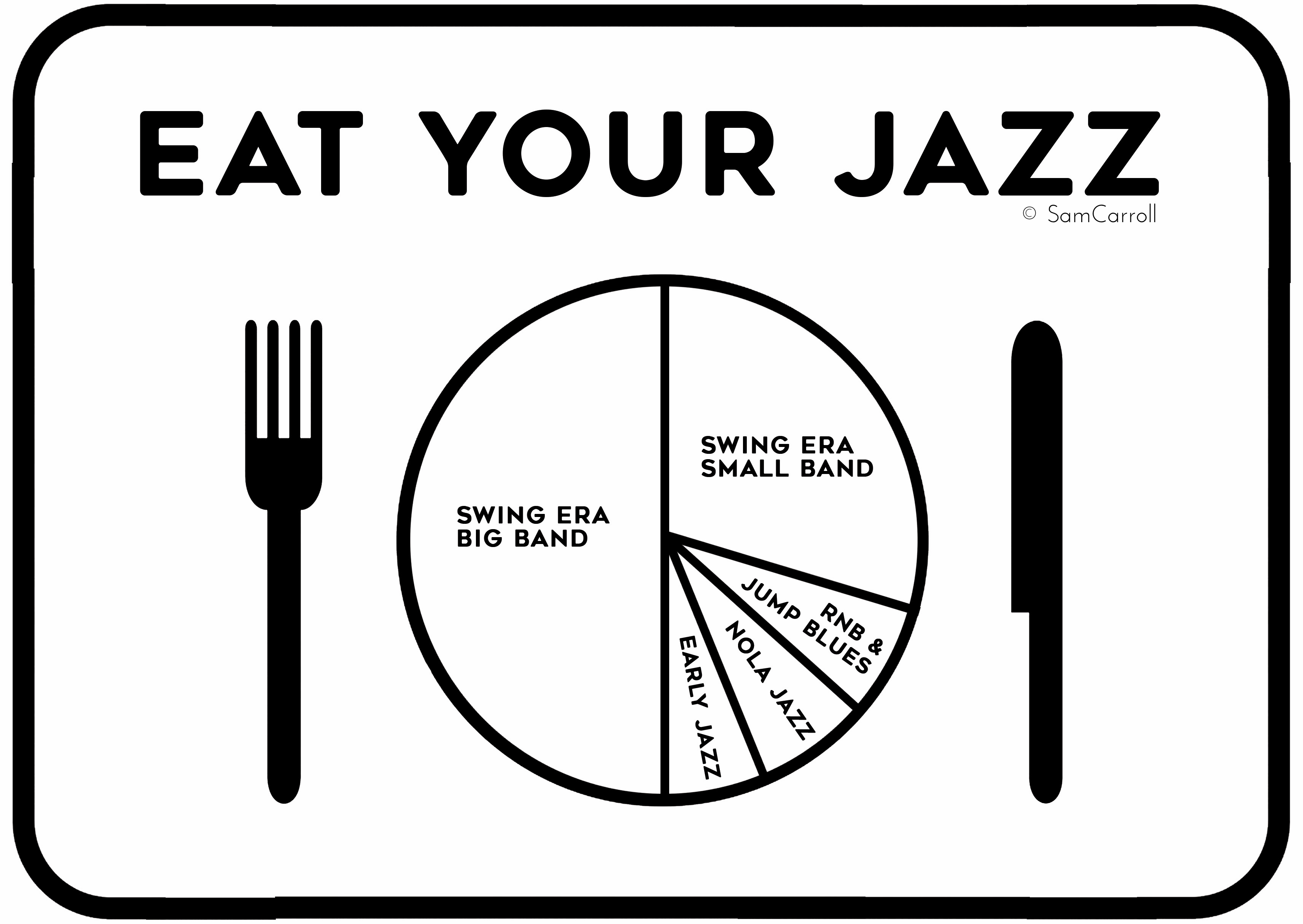

Look, the bottom line is that 30s and 40s classic swinging big and small bands doing proper swinging jazz (not jump blues or early rnb, not nola, not hifi, not 50s stuff) makes for brilliant lindy hop, balboa, and jazz dancing. It swings like a gate, it’s structurally predictable enough to improvise over, and it’s technically bloody sophisticated. When you add in the talents of people like Teddy Wilson, Billy Holiday, and Benny Goodman, you just can’t go wrong.

I’m also enjoying working with a range of tempos. Not just super fast, not just ‘medium tempo’. All the tempos. One of my goals this Herrang was to get West End Blues into a set at some point. It’s the best jazz recording ever. I did get it in there (in a slow drag set), but to me it felt like a continuation of the DJing I was doing in other sets. In part because I had a strong feel for Louis Armstrong this July. I played a stack of him in Vienna, and then in Herrang. I noticed that when he was with a good, solidly swinging band his playing just sparked light into the dancers. He was a true gift to the world.

Anyway, this is what I played.

Baby, Won’t You Please Come Home 137 1938 Pee Wee Russell’s Rhythm Makers (Max Kaminsky, Dicky Wells, Al Gold, James P. Johnson, Freddie Green, Wellman Braud, Zutty Singleton)

The Jumpin’ Jive 145 1939 Lionel Hampton and his Orchestra (Rex Stewart, Lawrence Brown, Harry Carney, Clyde Hart, Billy Taylor, Sonny Greer, Fred Norman)

The One I Love (Belongs To Someone Else) 150 1945 June Christy and The Kentones

Lover Come Back To Me 154 1941 Mildred Bailey acc. by Herman Chittison, Dave Barbour, Frenchy Covetti, Jimmy Hoskins, Delta Rhythm Boys)

Wacky Dust 150 1938 Chick Webb Orchestra (Ella Fitzgerald, Mario Bauza, Bobby Stark, Taft Jordan (v), George Matthews, Nat Story, Sandy Williams, Garvin Bushell, Hilton Jefferson, Teddy McRae, Wayman Carver, Tommy Fulford, Bobby Johnson, Beverly Peer)

D.B. Blues 155 1945 Lester Young and his Band (Vic Dickenson, Dodo Marmorosa, Red Callender, Henry Tucker Green)

‘Tain’t What You Do (It’s The Way That Cha Do It) 160 1939 Chick Webb and his Orchestra (Ella Fitzgerald, Dick Vance, Bobby Stark, Taft Jordan, George Matthews, Nat Story, Sandy Williams, Garvin Bushell, Hilton Jefferson, Teddy McRae, Wayman Carver, Tommy Fulford, Bobby Johnson, Beverly Peer)

Don’t Be That Way 147 1938 Teddy Wilson and his Orchestra (Bobby Hackett, Pee Wee Russel, Johnny Hodges, Allan Reuss, Al Hall, Johnny Blowers, Nan Wynn)

One O’Clock Jump 175 1941 Metronome All Star Band (Cootie Williams, Harry James, Ziggy Elman, Tommy Dorsey, J.C. Higginbotham, Benny Goodman, Benny Carter, Toots Mondello, Coleman Hawkins, Tex Beneke, Count Basie, Charlie Christian, Artie Bernstein, Buddy Rich)

[band set]

Strictly Instrumental 132 1941 Harry James and his Orchestra

Big Apple 166 1937 Teddy Wilson and his orchestra (Harry James, Archie Rosati, Vido Musso, Allan Reuss, John Simmons, Cozy Cole, Frances Hunt)

I Want The Waiter (with the water) 151 1939 Jimmie Lunceford and his Orchestra

Get Up 144 1939 Skeets Tolbert and his Gentlemen of Swing (Carl Smith, Otis Hicks, Clarence Easter Harry Prather, Hubert Pettaway)

Trav’lin’ All Alone 170 1937 Billie Holiday Orchestra (Buck Clayton, Buster Bailey, Lester Young, Freddie Green, Walter Page, Jo Jones)

Savoy Strut (WM 1001-1) 158 1939 Johnny Hodges and his Orchestra (Cootie Williams, Harry Carney, Duke Ellington, Billy Taylor, Sonny Greer, Buddy Clark)

Free Eats 163 1947 Count Basie and his Orchestra (Ed Lewis, Emmett Berry, Snooky Young, Harry Edison, Ted Donnelly, George Matthews, Eli Robinson, Bill Johnson, Preston Love, Rudy Rutherford, Buddy Tate, Paul Gonsalves, Jack Washington, Freddie Green, Walter Page, Jo Jones)

[band set]

Love Me Or Leave Me 162 1947 Pat Flowers and his Rhythm (Dan Perri, Charles Green, Arthur Trappier)

Don’t Be That Way 136 1938 Lionel Hampton and his Orchestra (Cootie Williams, Johnny Hodges, Edgar Sampson, Jess Stacy, Allen Reuss, Billy Taylor, Sonny Greer) 2:36

Leap Frog 159 1941 Louis Armstrong and his Orchestra (Frank Galbreath, Shelton Hemphill, Gene Prince, George Washington, Norman Greene, Henderson Chambers, Rupert Cole, Carl Frye, Prince Robinson, Joe Garland, Luis Russell, Lawrence Lucie, Hayes Alvis, Sid Catlett)

September Song 160 1948 Harry James Band Live

I’ll Build A Stairway To Paradise 163 1945 Eddie Condon and His Orchestra (Yank Lawson, Lou McGarity, Edmond Hall, Joe Dixon, Joe Bushkin, Sid Weiss, George Wettling)

Baby, Won’t You Please Come Home 137 1938 Pee Wee Russell’s Rhythm Makers (Max Kaminsky, Dicky Wells, Al Gold, James P. Johnson, Freddie Green, Wellman Braud, Zutty Singleton)

Frenesi 147 1940 Benny Goodman and his Orchestra (Jimmy Maxwell, Irving Goodman, Alec Fila, Cootie Williams, Lou McGarity, Cutty Cutshal, Gus Bivona, Skip Martin, B Snyder, Georgie Auld, Jack Henderson, Fletcher Henderson, Bernie Leighton, Mike Bryan, A Bernstein, Jaeger)

The Goon Came On (GG) 144 1944 Jimmie Lunceford and His Orchestra (Joe Thomas)

[band set]