This is a ‘quick’ post about some things I’ve been thinking about in my own teaching lately. I teach lindy hop a couple of times a week, and I teach solo dance once a week.

[off-topic ramble]I recommend doing that, by the way, if you’re into solo dance. Even if you only have five students in the room, that’s still six people in your scene who are working hard on solo dance, improving their skills and having a bunch of fun. And I can guarantee you, coming up with class content each week will make you a damn good solo dancer. Or at least a much better solo dancer. Do it. DO IT!

There’s a real difference between planning a class, learning a routine, understanding your own movement, and then then teaching it, and just practicing on your own. I think there’s something of a feeling in many scenes that solo dance is something you just work on on your own, and that it just has individual styling, that it isn’t a challenging discipline the way lindy hop is. Of course, you can do that, but if we approach lindy hop as something requires a degree of guided discipline, why don’t we think of solo dances this way? You needn’t structure your class in conventional ways – you can approach it as a guided practice session or a workshop, but there’s a real difference between ‘practicing’ and the discipline required to teach or run a structured session. And that difference will really lift your dancing. Also: FUN.[/]

Anyways, I do this every week, and have done for about two years now. I’m not the world’s best dancer, by any means. I’m not the best lindy hopper or solo dancer, and I’m steadily discovering the limitations of age, particularly as 40 is not so much on my horizon, as coming through my front gate with a shopping bag full of high-end chocolate and a 6-pack of Teen Wolf DVDs. So keeping on top of my own skills seems more and more important. I’m working on my fitness, strength, and mobility now, so that I can be like Frankie – still dancing in my 90s. And I love it. I love the fun of all this, and I love the challenge: it’s complex stuff, and I relish the mental challenges as much as the adrenaline.

My lindy hop teaching and my solo dance teaching are bound together. I can’t separate the two, and the more teaching I do, the less likely I am to want to separate them. I can’t imagine teaching a lindy hop class that didn’t have a significant emphasis on individual movement and dancing. You know that line, “If you can’t dance on your own, how can you expect to dance with someone else?” Well, it’s true. It’s so true. When I go into other people’s classes, I’m always stunned that the students spend the entire class touching someone else – they never dance without touching a partner! They’re missing half the fun!

I think, though, that many of us are on top of the idea that you can ‘add solo jazz to your lindy hop’ by doing a bit of partnered boogying-back and boogying-forward, or a bit of face to face charleston or whatevs. If you’re not… well, I don’t know what you’re doing.

When I started teaching, I was all ‘omg students need things really simple! We can’t mix rhythms, or they’ll freak!’ and then I started watching videos of Frankie Manning teaching.

link

link

(And one video that I’d like to talk about at another time, because it’s a brilliant example of how good social skills translate to brilliant dancing skills.)

That’s just two, but if you search for Frankie Manning classes on youtube, you’ll find a million of them. And he doesn’t pull punches on the rhythms. Students learn heaps, HEAPS of different rhythmic sequences in just one class – and that’s beginners. BEGINNERS.

When I saw that, I got my shit together, and I started teaching multiple rhythms in one class. That might include step-step-triple-step, a break step (step-step-hooold-a-diggety-diggety-da-stomp off!), a mini-dip (step step, down-clap, up-snap, hold, stomp off)…. HEAPS of things. And students just absorb them. There doesn’t seem to be a limit to the number of rhythms humans can learn in one class. They’re capable of recognising and then reproducing complex rhythms from memory, with THEIR BODIES. That is just amazing. It’s like learning an endless list of numbers and then combining them in different sequences, but then doing aerobics at the same time.

And I haven’t met a student yet who couldn’t do this. Some peeps need a bit more time, or they need a slightly different approach, but everyone can do it. We start by demonstrating the rhythm with steps, or with claps. Then we get them to clap along. We don’t use counts, we use scats. Then we teach them the steps or movements that correlate to the rhythm. Then we might add on turns or movements through space.

And then, once they’ve learnt that on their own, they can learn to lead/follow it with a partner! FUCK! That is AMAZING!

I’m talking about complete beginners – first class ever people. And they LOVE it. They just love it. There’s something about dancing or clapping out a complex rhythm with a room full of people that makes people feel extremely big feelings. To me, it feels like singing in a choir – that moment when you are just a part of a huge, big beautiful thing that is beyond rational thinking. It is just magic. I see students have that feeling in classes when we’re clapping or dancing out a really nice rhythm.

Wait. Where am I going with this? I said I was going to list just two ways of ‘putting solo dance into your classes’. I’ve already listed two or three. But they’re not the ones I’m interested in. To my mind, this stuff should be your base line. Take Frankie as your model: your lindy hop should involve countless moments of ‘jazz dance’. You should have layers and layers of different rhythms happening in your dancing – because we are talking about a dance that is jazz made visible. Polyrhythms are us. Get on it. It’s fun.

So here are my specific items. This is what I take as my own personal rule. I don’t care what you’re doing in your classes, really, but this is where I get a sense of purpose, and how I find pleasure in teaching. I think it improves my teaching, and it brings me so much joy. So I’m recommending it to you.

1. Get serious about solo dance.

Lennart Westerlund told me that it’s worth learning to tap dance not necessarily to get good at tap, but because it improves all your other dancing. I reckon it’s because tap is really fucking hard, so everything else gets easier because you skill up. But I think the same applies to solo dancing. If you learn to dance on your own, your general skill level will increase massively.

Specifically:

Solo dancing is uncompromising. There is no partner to cover your mistakes or weaknesses. You will just become a better dancer. That means that your balance will improve (and balance is of course about core stability and control). Your reactions will improve (which is about being able to use the right muscles at the right time in the right order). Your proprioception will improve (which is basically your ‘body awareness’, and which translates to actually doing what you think you’re doing, which means you’ll be doing what you’re saying, which means you’ll actually be demonstrating the things you’re teaching your students). Your fitness will improve. Your sense of timing and rhythm will improve.

Timing and rhythm are different: timing is about understanding ‘the beat’ – that inexorable, consistent heart beat at the core of the song – and rhythm is about variations on that beat – layering up increments of time. Most solo dance is much more complex than lindy hop. When we teach solo dance, we don’t think in terms of 8 counts or even phrases much any more. We think in terms of parts of a beat. When you teach lindy hop, you might think ‘swing out, circle, charleston’ when you’re planning a class. But when you’re solo dancing, you think ‘hoo-ha, shakkety da, shakkety da, ba. ba-du-ba-du-ba DA’. So your understanding of timing, rhythm and music gets far more sophisticated.

Another key thing that solo dance improves is your ability to move through space. I find brand new students have most trouble with turning or spinning their bodies, and with moving their bodies, while they do a rhythm.

I’ve recently started teaching a group of teenagers, and their problems lie more with staying focussed and concentrating – they are endlessly energetic and athletic and have much better proprioception. Older people can focus and learn complex sequences, but their proprioception is weaker – they don’t know where their arms and legs are. A mixed group is the best option, because the two balance each other out – peeps with good proprioception provide good models for those without, and people with good concentration model good focus for those who don’t have it.

But dancing on your own before you dance with a partner helps you figure out what you’re doing, so when you then come to leading or following, you have a better idea of how your movements are affecting your partner, and you can sort of mentally set aside the information you’re getting from your own body, and ‘hear’ their body and what it’s doing.

So if you start getting into solo dance – even if you never teach it, never social dance it, never even bother practicing (much) – your lindy hop classes will improve massively. And, to be honest, if you can then go on teaching without any jazz elements in your classes, I’d be very surprised. Learning more about jazz dance opens up a whole new world of lindy hop. I feel as though getting serious about solo dance has suddenly added depth and richness to my understanding of lindy hop. It’s a bit like going from only seeing in black and white to seeing in colour – you don’t know what you’re missing, and then suddenly OMG, you’ve been missing SO MUCH! I started getting into solo jazz dance in a more serious way about 2004, but it’s only recently, with teaching, that I think I’ve actually really understood how essential it is to lindy hop.

And I want to add a caveat: doing other types of dance is very important. But historic jazz dance from the 1920s and 30s is what you really need. This dancing with its roots in jazz music, and you really need to get into thistradition. But, honestly, if you have a chance to do a dance class, take it. Doesn’t matter what the style. Dancing is good for you.

2. Do a big apple warm up

What? Do this at the beginning of all your classes:

link

I cannot imagine starting a class without a warm up. I was teaching three classes in a row last year, and we started each with a warm up. Why?

You need to warm up your body.

Even if you’ve been exercising the past hour, you need to get your body focussed and ready. Injuries are bad news. So start with less strenuous movements, and don’t go 100% just yet.

You need to warm up your mind.

Dancing on your own gets you focussed and improves mindfulness (which is about being in your body and present in the moment). A fun, relaxed warm up helps you relax and enjoy your body – to make friends with the music and your body!

A good, relaxing, fun warm up energises your body and energises your mind while it calms and centres you. In less hippy terms, warm ups where you do simple, repetitive movements that are less than full extension/energy help your proprioception (where are my hands now? where is my foot?), and they shift your focus from thinking your way through steps, to moving your way through steps.

I find a warm up helps relax a class. Brand new students, in their first ever dance class ever, are often a bit nervous or unsure about how to act in a class. A big apple is simple, repetitive and calming. It helps them get focussed.

Students and teachers often come to a class excited or distracted. A warm up helps you focus and brings your attention in to the group.

A circle is a nice shape, because it provides a nice, physical focus for your attention – into the middle of the room. There’s no one behind you, so you don’t have to worry about ‘covering your back’, and there’s no one in front of you, so you can see clearly. It’s also a nice symbol of equality and group-ness, which is helpful.

And just as when I was tutoring in universities I used the first class to model how we would treat each other, handle discussions and conflicts, the warm up models how we will be in the class for the rest of the hour – relaxed, fun, join in when you can, no mistakes, just fun.

In more nerdy teaching terms, the warm up is the most important part of a class, for me. That’s where I do most of the hardcore teaching work. I always make sure that the basic elements of whatever we’re teaching in that class are included in the warm up. So if we’re doing charleston, there are kicks and walking with kicks, and some pivoting. There’s walking in rhythm (because all dancing is really just fancy walking). And if we’re teaching a solo class which focusses on a particular step or rhythm, I make sure that’s in there too. But it’s fun, so no one really realises they’re doing the hardest part of the class.

When we begin the warm up, we always say “The goal here is just to get sweaty, to warm up our bodies. There’s no right or wrong, just get in and have some fun.” This actually sets the tone for the entire class: there is no right or wrong. Get in and have a go. Don’t think about it, just dance. We make jokes and do the funnest, funniest steps we know. Because they are awesome, but because they relax us all as well. Laughing, relaxed dancers are better dancers (watch that last video of Frankie above – he is all over that). The idea of ‘just join in’, where you begin the move and the students join in after watching a bit, or just join in straight away (whatever works for them) tends to carry on into the class: if I’m demonstrating a rhythm by clapping, or stepping, they just naturally join in after a while. This is fucking AMAZING, and so exciting when it happens in class. I get a thrill every time.

If you do a step or move for a whole phrase (and the length of time we do a step depends on the group – we spend longer on each step with newer students, make faster changes with more experienced dancers, and vary the tempos this way too), students naturally learn about musical structure. They start picking up phrasing and 8s and all that stuff, and you never even have to mention it. That’s also amazing. No more counting people in!

And finally, the transitions between the steps (which is often the hardest part), become low-pressure points in a warm up. They’re usually the point where people laugh (at themselves), and that is FABULOUS. There are no mistakes in this scenario: there are just points where we laugh as we try something new.

We usually spend about 10-15 minutes on these warm ups. The first part is a big apple style warm up, but then we often transition seamlessly into an explicit description of the key rhythm for that class. I might say, after the song has ended (and I don’t actually describe what I’m doing when we’re warming up to a song – just demonstrate), “ok, here’s one more rhythm I want you to try,” and I demonstrate the triple step. I usually try to clap it, scat it, and dance it. If they want to join in with each step naturally (and I want them to), that’s great, otherwise I prompt them. I get them to do it on both feet. Then I say something like “Remember this one?” and we walk, which is always funny. Then I might say “Ok, let’s combine them like this” and I demonstrate the step-step, triple-step rhythm (hoo-ha, shakky-dah; clap-clap, clap-clap clap). I find it’s worth taking a second to be very clear about this, and to articulate what I’m doing. It’s essential to do it on both feet.

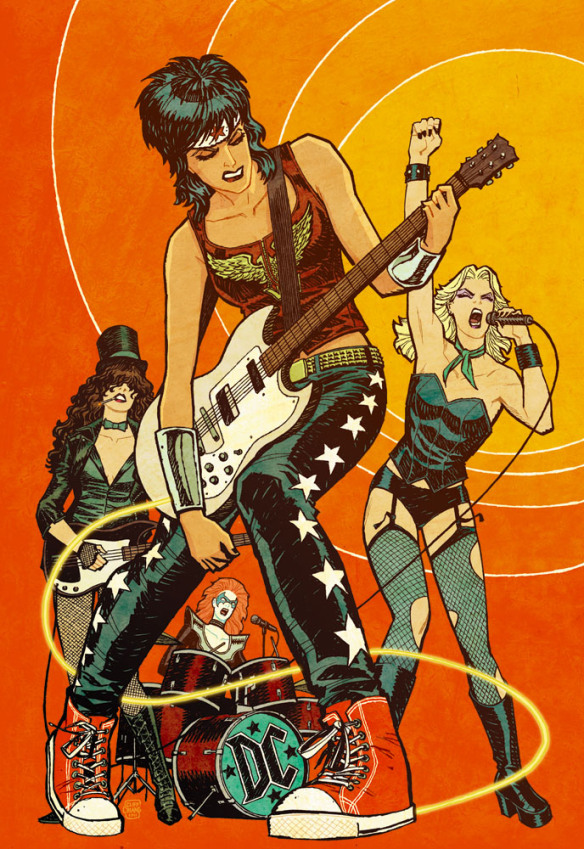

(One of our students made this fab shirt. You can see more of his stuff on etsy and on madeit)

All this is wonderful stuff, and, to be honest, I enjoy it so much more than the rest of the class. It’s like a game, where we learn really fun stuff. I am beginning to think that this might be the way to structure all our solo classes, and that we could shift our beginner solo classes in particular in this direction. My eternal teaching goal is to talk less, dance more. My second goal is correct less, let people practice and practice and dance through their problems until they figure it out themselves.

That last one is important because it means you’re not correcting anyone ever, which means your classes are much more positive. And I think it’s much more useful for students to discover how things work through experimenting, rather than having it all laid out for them. I do have to continually fight the urge to correct everything students do, to send them out of class ‘perfect’. But you have to remember that learning is a long process: you do not just insert a shopping list of items into students during a class. Students must learn to learn, to come to dance through their own process, and in their own time. Your job as a teacher is to be a guide to learning. So that means, in practical terms, that you need to give students quite a bit of time to work through steps or moves in class, practicing and trying stuff out. Let them dance a whole song with a partner or two. They will figure it out, and you won’t need to correct them.

Corrections are problematic because they tell a student, even if you are being really gentle, ‘You were doing this wrong’, which is bad news for self esteem. They also reinforce the higher status of the teacher, and rob the student of power and status. We want happy, confident students who enjoy exploring learning and dancing. As a friend of mine said, our job as teachers is to help students fall in love with dancing. As Lennart said, we must make friends with the music. That’s the most important thing we can do, so everything I want to do in class should be aimed at that goal. Joy. Happiness. As Frankie said, “For the next three minutes, you are in love.”

But I am a total control freak perfectionist, so that is really, really difficult to do. But I guess that’s my challenge as a teacher: let go. I suppose that’s the other part of all this, particularly my emphasis on improving my own solo dancing to improve my teaching. Approach teaching as a learning process for me. I can’t imagine I’ll ever know everything or have perfect teaching skills. And I really like that. It’s as though a whole new world of dancing has opened up for me. There’s a richness and challenge and delight that I hadn’t thought of before. And it’s classes of students who give me this opportunity, so that idea of ‘cherishing the students you have’ is a part of that: teaching is an opportunity for me. And I want to approach my teaching practice as a practice – a process of change and learning and development.

As I type this, I keep thinking about the way the Hot Shots teach. They’ve been teaching this way for twenty, thirty years. And I’ve been learning from them all this time. But it’s as though I’ve only just become aware of all these sneaky, student-centred learning techniques recently. I wonder if they figured this stuff out through practice, through working with the old timers (and Lennart said that the old timers would just say ‘hey, do this!’ and then they’d do that – no technical discussion at all), or through the benefits of coming from a socialist Swedish education system. A combination, I expect.

So, in sum, I think it’s really important to put solo dance into your teaching. And these are the two most important methods: become a solo dancer yourself; do a solo dance warm up.