So you might have noticed a lack of WHM posts lately. Here is my litany of excuses:

– Hayfever has put me down for the last few days. Big time.

– We discovered a leak into the concrete slab of our flat last week, and have spent a week moving our ONE HUNDRED BOXES OF BOOKS and associated bookcases UPSTAIRS so we can then rip up the carpet in smaller sections to expose the slab. It is now ‘drying’. Sydney has had a spectacularly damp and mild summer, so this ‘drying’ is not happening. We will not discuss leaks, mould and allergy connections.

– I have some other projects on the go which have sucked up my spare brain time. I have, however, quite sore shoulders from so much computer work, so that’s a good thing. I guess. Writing: I did it. Websites: they are maintained!

– The theme I set myself just didn’t inspire me the way the month of women dancers did last year. It seems I am a dancer first and a music nerd second.

– I have a limited block of time set aside for dancing during my day/week, and that block has been filling up with teaching, admin for the classes, various DJing gigs, getting rid of some dance commitments (why is that harder than actually doing the jobs in the first place?), a workshop thing I’m running in May (which will be SQUEE), thinking about promotions and advertising in a long term way (rather than just responding to things), trying to sort out new sound gear for one venue (gee, that task has totally not been done), and then I take on ANOTHER DJing project, which will be super fun, but is perhaps overly ambitious for someone who is supposed to be giving up ocd impulses.

I told you it was a litany.

I had some ideas for posts:

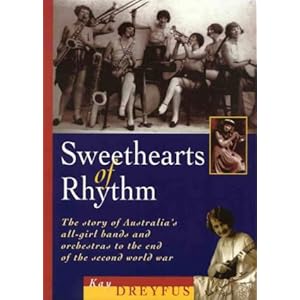

– the role of all-women bands in the first fifty years of the 20th Century, and the contribution they made to jazz (big);

– women in the early days of the recording industry (in which vocal blues and blues queens played a big part, and in which race records are really important, because they marketed those blues queens to black audiences so effectively the white labels started trying to screw them over and steal their ideas and artists), most especially the women working for record labels;

– other stuff.

A couple of books have just arrived from teh interkittens, so I will read some of those and then forget to write anything down. But first, I’m going to ramble on with a long, poorly-referenced bundle of ideas which really need some proper thought. I should really have written about women in jazz history, shouldn’t I? But this is an interesting topic, and one I keep coming back to in my own reading. When I get done with two of my new books, I’ll have some more cleverly thought out things to say. But for now, here’s a big ramble.

I’ve also wanted to comment on Peter’s Jazz and the Italian connection post because it touches on some issues that I’ve thought about for a while. And that are bizarrely relevant to Australian mainstream politics at the moment.

To sum that one up, I’m not suggesting that this is what Peter is doing (because the man knows his shit), but I do think it’s misleading to argue that the exclusion of the ODJB was a consequence of ‘reverse racism’ or ‘political correctness’ favouring black artists. Which is what is argued by a number of truly dodgy scholars in jazz studies (I’m going to have to check my notes more thoroughly for those references – bare with me, k?)

From what I can tell, however, Peter is arguing something slightly different: that it is important to discuss the ODJB in a history of jazz. For all sorts of reasons. I’d certainly agree.

My interest would be in how the ODJB presented a more palatable ‘white’ jazz to mainstream audiences at the same time as race records (labels targeting black audiences) were selling ‘black’ jazz to ‘black audiences’ and live music venues were also presenting jazz in quite racialised terms (the Cotton Club itself is a good example – black musicians presented for white audiences). As Peter also implies, the ‘white’ and ‘black’ dichotomy isn’t all that useful. The Italian musicians (and French and… everyone else) were definitely ‘othered’ at the time – they weren’t ‘white’ (ie Anglo celtic), but they read or looked white, and that was important when the look of an artist was being established as a key marketing tool. So my question would perhaps be ‘What was to be gained by, and what were the consequences of making the ‘otherness’ of non-anglo celtic musicians invisible in jazz histories?’

What I think happened is that the favouring of black artists was a consequence of racism in the 1930s and 40s. In those moments when ‘the origination of jazz’ was first being written (by white authors) the ‘popular jazz press’ (ie newsletters, magazines, etc) and other writing about jazz favoured black musicians because this approach favoured myths about race and creativity.

Just like the Ken Burns ‘Jazz’ doco, this approach follows particular individual musicians, positioning them as unusual, almost magical figures who overcame poverty/geography/BEING BLACK because they were somehow touched with a magical gift. In reality, these few figures were hard working people who worked within black communities, and then the wider American culture, experiencing racism every day. Their skills weren’t ‘god given gifts’ but the fruits of hard labour as well as talent and community support, and the advantages of being male musicians in an industry that made it very difficult for women to get gigs. This is something George Lipsitz discusses in his work “Songs of the Unsung: The Darby Hicks History of Jazz.”

This approach to jazz history – telling stories of miraculous black achievement as an aberration from the norm – reinforces racist archetypes. If the stories were told as stories of hard work, the musicians positioned within communities which fostered and encouraged their creativity – the authors would have to revise their ideas about black and white creative practice. They’d have to accept the idea that musical genius happens in all communities, regardless of race or class or gender. But that the factors which make it possible to realise this genius are absolutely defined by class and privilege and power and opportunity. Here’s a long quote from Lipsitz discussing these things:

The story of jazz artists as heroic individualists also overlooks the gender relations structuring entry into the world of plying jazz for a living. Women musicians Melba Liston, Clora Bryant, and Mary Lou Williams can only be minor supporting players in this drama of heroic male artistry. Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday are revered as interpreters and icons but not acknowledged for their expressly musical contributions. Although [Ken Burns’] Jazz acknowledges the roles played by supportive wives and partners in the success of individual male musicians, the broader structures of power that segregated women into ‘girl’ bands, that relegated women players to local rather than national exposure, that defined the music of Nina Simone or Dinah Washington as somehow outside the world of jazz are never systematically addressed in the film, although they have been investigated, analyzed, and critiqued in recent book…” (15)

The ODJB was one of a number of white bands working at the time, and they were well positioned to take advantage of a new recording industry and the possibilities of clever promotion. I think that they are/were glossed over by many music historians not because they weren’t black, but because they didn’t shore up racist archetypes.

The other interesting part of Peter’s post discusses the role of Italians in the early days of recorded jazz (and jazz history). This is much more interesting. There’s a chunk of scholarship about discussing the role of jewish musicians in early jazz and radio, which I think can be helpful. And cities like New Orleans (and New York for that matter) had large migrant populations: jazz is (as Winton Marsalis goes on about, ad nauseum), a gumbo. It is a mix of cultures and musical traditions. So it makes perfect sense to explore the Italian contribution.

Lipsitz, George. “Songs of the Unsung: The Darby Hicks History of Jazz,” Uptown Conversation: the new Jazz studies, ed. Robert O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, Farah Jasmin Griffin. Columbia U Press, NY: 2004: 9-26.