A dance band playing at the Jack Keating dance studio c1930. Look at those decorations on the wall. Such beauty.

Category Archives: academia

Kill me now.

I promised myself that I wouldn’t engage with this topic. But you know, post-event boredom, feeling a bit bolshey. Time to ramp it up.

This is the sort of post that I get heaps of hate mail for. Usually with a few sooky comments by people telling me to:

– stop hating

– just relax

– be happy the dance is getting some exposure

– be thankful the community is getting ‘grown’.

But FUCK me.

…multiple forms of the dance that was created in late 1920s Harlem by Frankie Manning are growing ever more popular (source)

I had a quick look at this book the other day in the book shop, and I was pretty unimpressed. Nice type, nice photos, nice etc etc. Entirely lacking in substance. Reminded me very much of this 2009 book:

But honestly. Fucking HONESTLY. Whoever wrote the blurb for this book needs to:

a) find out who Frankie Manning was, and what he did (tip, he didn’t create ‘swing dancing’ in the 1920s),

b) have a think about what the business hosting this website does,

c) just stop.

If this line is in the book (and I remember some dodgy bits like this in my quick flick), then the author needs to take a long hard look at himself.

Honestly.

…because I can’t leave this here.

1. Frankie Manning didn’t invent lindy hop. A whole heap of people were dancing lindy hop before he got to it, and as with all vernacular dances, lots of people had a hand in ‘making’ and remaking it. Frankie himself would have been the first to make this clear.

2. Let’s talk about George Snowden at some point, and the ‘swing out’ or ‘breakaway’.

3. Let’s talk about WOMEN. Who were these leads’ partners? You can’t invent a partner dance on your own, you can’t do new and creative things in a partner dance without a partner. So fuck THAT noise.

4. I know that someone somewhere is trying to make a point about Frankie and the first ‘air step’ and I can dig that. But that is not where we will end this discussion: who pulled out this first over-the-top with Frankie? ie who was his partner? And what other sorts of acrobatic steps were happening before these guys pulled this out in a comp?

Double Dutch Divas

I’m reading through Kyra D. Gaunt’s book ‘Games Black Girls Play’ again (!!) and there’s a fun bit about double dutch, or skip rope with two ropes.

There’s a section where Gaunt goes to jump with the Double Dutch Divas (or Shout Sister Shout). She talks about two things that were really interesting: a) call and response, or crowd participation, and b) how to get into the ropes.

One thing I’ve always disliked about predominantly white, middle-class, or mainstream staged performances (of any kind), is the lack of support the audience gives, or can sustain, when someone is singing or performing. Even when invited, they don’t seem to understand that clapping encourages a better performance – it gives life to the moment – which gives positive feedback to the performers during the performance. All those in the room who were not turning ropes or jumping have their eyes turned to the center action, while their bodies are vibing to the beat. Our mouths generously shout alrights, umphs, andyeahs though not to distract her focus or detract her from the moment (p 172 Games Black Girls Play.)

I’ve written about call and response and audiences in Live music: listening or doing, and about call and response one million times before. But I like the way Gaunt talks about this group of older women using call and response to encourage each other, and to include everyone.

At last, it was my turn. I was thirty-seven years old and there was no question that I was a black girl, with our without knowing how to double-dutch. Since I knew I would be entering the ropes sooner or later, I had been watching how Lady Di, Faith, and Spirit entered them. When I was a kid, entering the ropes was always my stumbling block….

Lady Di got into the ropes effortlessly. It seemed she and the others didn’t even think about it. But there had to be a ‘rhythm method’ that protected them from getting hit by the oscillating ropes. I watched Di put her hand out in front of her body as she moved up to the perimeter of the ropes and felt the gaps between them. Her whole body moved with the action – reminding me of the young girls rocking back and forth toward the ropes before they entered (p 174 Games Black Girls Play.)

This section really caught my attention, because I’ve always felt like going into a jam is like getting into a skipping rope. You have to find the rhythm, put it in your body, before you get in there. And I’m always pretty strict about when I go in – I need the general vibe of the jam to be right. I don’t want to cut someone else’s lunch, especially if they’ve been getting ready to get in for a while. I want to match the feel of what I do with what’s happening in the song (I don’t just mash my favourite steps on top of any old part of the song). It really feels like getting into a skipping rope.

I always think it’s a shame that so many lindy hoppers today don’t use the jockey step before they get into a jam.

Watch the couple behind and a little to the right of the dancers in the jam (the man is wearing a pale hat and pale trousers and a dark shirt) from about 0.44. They’re doing a sort of step-tap rhythm, which is a sort of jockey:

(Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers in Day at the Races)

The ‘jockey’ is named for that idea of ‘jockeying’ in place – “…probably relates to the behaviour of jockeys manoeuvring for an advantageous position during a race…” (from my computer’s dictionary).

This gets your body and brain ready to dance – it puts the rhythm in your body. It also signals to everyone around you that you are getting ready to dance – you are literally jockeying with the people around you, looking for a good position (musically and physically) to get into the jam.

Any old how, just thought I’d plop this all in here while I’m thinking about it.

Uses of history: Frankie as teaching tool

A discussion came up on the facey the other day about how leads can deal with rough follows. It caught my eye, because I’d just had a dance with someone the night before which was particularly rough. I was leading, and the follow really moved herself through steps in a fierce way which left me feeling a bit sore. It also dovetailed nicely with my ongoing thinking about how to prevent sexual harassment in lindy hop.

On that last topic, I’m approaching this with a different strategies:

- Developing a clear code of conduct for behaviour

– (in progress) - Teaching in a way which helps women feel confident and strong, and provides tools for men looking to redefine how they do masculinity.

– using tools like the ones I outline in Remind yourself that you are a jazz dancer - Teaching in a way which encourages good communication between leads and follows.

– I am keen on the rhythm centred approach as a practical strategy. Less hippy talk, more dancing funs.

– I like simple things like talking to both men and women about being ok with people saying no to you. - Developing strategies for actually confronting men about their behaviour.

– I talked about how I do this in class in Dealing with problem guys in dance classes

– I am totally ok with telling men to stop pulling aerials on the social floor because it’s a clear ‘rule’, but more ambiguous stuff is stumping me

– I’m trying to figure out how to do it in other non-class settings

– I’d like to find a way to skill up men so they can do this stuff too; ie it’s not just women’s jobs to deal with men sexually harassing women.

I seriously believe that feminist work needs to be practical. High theory and abstract conversation is very important, but for me pragmatic feminism means actually doing things. It’s important because it powers me up and makes me feel strong, but it’s also important because you know – actually DOING something. It can be quite hard and scary sometimes, because you are agitating, you are disturbing the status quo and you will attract some shit. Men don’t like to be told they’re doing dodgy stuff (and lefty men get particularly upset by this), especially when it’s a woman telling them. They often respond with physical intimidation, which is scary. And there can be social consequences for women which suck in a social dance community like lindy hop.

So, for me, I try to do this work in a way which isn’t too confronting or frightening for me. And which isn’t too confronting for other people. Feminism by stealth.

Where does Frankie Manning fit into all this?

Just in case you’ve been living under a rock (or are just new to lindy hop), Frankie Manning was one of the best dancers, choreographers, and troupe leaders of the swing era (1930s-40s). He’s generally positioned as ‘second generation lindy hop’, and credited with inventing the first public air step with his partner Freda Washington.

More importantly for modern lindy hoppers, he came out of retirement in his 60s to ‘teach us how to dance’. He taught people to lindy hop from the 80s until he passed away at 94 in 2008.

He wasn’t (and isn’t) the only old timer to do this. But most significantly, he had a very joyful, accessible approach to dancing, he didn’t mind that we all sucked, and he was prepared to work with complete amateurs, even though he really didn’t have any experience teaching total noobs or of teaching in a formal classroom context.

So Frankie holds a special place in many modern lindy hoppers’ hearts, and many of us take his example as near-gospel.

There are a range of problems with this approach, and I talk about them in Uses of history: a revivalist mythology. I basically say that I think we should be wary of uncritically using Frankie and his approach when we teach and talk about lindy hop. There are a host of political issues to consider when we appropriate his image and approach, both in terms of race, ethnicity and class, but also in terms of gender. Basically, he wasn’t perfect, and we have to be careful we don’t literally use him and his work for our own ends. And we have to be careful about how we use historical discourse in our classes.

So that’s my disclaimer, really: the next bit of this post is written with an awareness that I am a white, middle class woman writing in a developed, urban city in the 21st century. I am taking the words and teaching of a black, working class man of the early 20th century and using them for my own ends. I try to couch that with respect to Frankie’s memory, by name checking him and giving him credit for his work. I direct students to footage of his dancing, and to his own words.

I also make it clear that I am framing his work from my own POV and goals as a teacher and dancer. I didn’t know Frankie, and I only met him a few times and learnt from him a few times. So I tread lightly in his memory, and I try not to speak for him. But I am inspired him – by his dancing, by footage of his classes, by the mark he left on dancers who I learn from now and admire very much. I try to work with respect for his memory and for his work; he is an elder in our community, a custodian of knowledge, and important.

So here is something I wrote on the facey.

It’s about how I ‘use Frankie Manning’ in class to counter misogyny and sexism and to promote a type of connection that privileges creative collaboration, mutual respect, joy in dancing, and flat out badarse dancing.

I have trouble with rough follows every now and then. Especially ones who’re in troupes or do a lot of performing. They’re used to really physically strong leads (I don’t have the upper body strength of a man). I’ve had some bad shoulder and back twinges lately, despite my best efforts to improve my own technique, core stability and so on. As with dealing with rough leads when I’m following, I figure a rough follow is a partner who isn’t listening or paying attention to me because they’re stressing. At least I hope that’s what it is – it’d break my heart if rough follows were deliberately rough.

So the first thing I do if my partner is a bit rough, is to get us in closed position and tell a joke. But not too close a closed position, especially if they’re a woman who’s obviously weirded out by dancing with another woman. I’ll try to do something to distract the follow from being fierce and doing what they think I’m leading. Once we’re both chilled, and paying more attention to each other, I do super simple steps with a lot of emphasis on jazz feels and call and response – they do something, I echo it. That helps us both get on the same page. Then I build it out from there, adding in open position, etc etc.

So my first response to a rough follow is to become a really clear, yet incredibly gentle, responsive lead. And I make my basics the very best I can, so they feel confidence in me.

I’ve been using Frankie Manning as a good guide for safe dancing lately when I’m teaching. He would usually teach from the lead’s perspective, so I find it very helpful as a lead working to make a dance with a follow really comfortable and nice.

That means I’m emphasising:

– Looking into your partner’s face.

This is the most important thing I know about lindy hop. LOOKING into your partner’s face. It was the one big thing I learnt in the Frankie track at Herrang last year (where all the classes were taught by people who’d worked closely with Frankie). Once I noticed it, I was stunned by how infrequently partners look into each other’s faces.

It’s good for your alignment and posture relative to your partner, but it’s also good for making you connect with another human as a person, it helps you learn to observe your partner and recognise when they feel pain/scared/happy and it’s good for making you lol.

-> follows are less likely to throw themselves through steps if they’re looking at your face and seeing you flinch in pain. They’re also distracted from the move by the genuine human connection, so they stop pre-empting or rushing or panicking.

– Call and response rhythms as fun steps.

They make you pay a LOT of attention to your partner, visually and physically, so you can ‘hear’ what they’re doing rhythmically. This is good for interpersonal communication (how is my partner feeling?) and learning how to recognise physical signals (what does a suddenly-tight arm tell me when I combine it with their facial expression?)

-> this is the next level of looking at your partner. So follows stop pre-empting and are really there with you. And because you’re really listening to them (everyone calls, everyone follows), they feel like you’re listening to them, so they feel more confident and worry less about ‘getting it right’ and rushing or hurting you.

– Your partner is the queen of the world.

We say this a lot: your partner is the queen of the world (whether they’re leading or following, male, female, whatevs). This means that you have to look at them (and we model how to be impressed by/respond to your partner positively), and the ‘queen’ should then feel confident enough to bring their shit.

This teaches you to be connected emotionally with your partner, and to recognise how your positive response to a partner’s dancing can make them feel good and then bring their best shit.

-> follows bring incredible swivels and generally become the queen of the world. They pay more attention to you as a lead, and they feel like you’re really listening to them, so they reciprocate.

– Scatting.

Brilliant for improving your dancing, but when your partner is scatting, you can hear them, so you’re connected with them in an additional way.

-> makes follows lol.

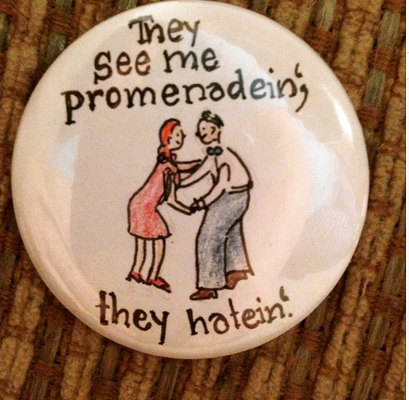

– Frankie thought the most important lindy step was the promenade*.

It’s in closed position, it requires lots of communication to walk together without kicking each other, and it has lots and lots of variations with lots of different emotions. It teaches you to communicate with someone, and you have to look into each other’s faces a lot, and be ok with that.

You get to hold someone in your arms, which means you have to be respectful.

*Lennart says so, so it’s probably true :D

-> I find some follows aren’t so ok with being so close, so I have to pay really close attention to them to find the ‘comfortable’ distance/connection. This makes me do my very best dancing. I try to put me in front first, so the follow feels more comfortable (follow first means they’re walking backwards – eeek!). I do pecks to make them lol, or rhythmic variations. I respond to the variations they bring.

– You’re in love for 3 minutes.

Doesn’t have to be romantic love. But for that 3 minutes, this person is the most important person in the world. You look at them, you lead steps you think they’re like, you do your best to realise the step or move their aiming for, you work to make this dance work.

To me, this is excellent mindfulness. It makes it hard to be rough with your partner. And when someone is feeding all those good vibes back at you, you smile and do your very best dancing.

-> follows become the queen of the world. They listen to you, and even better, they bring things to the dance.

I think it’s worth looking at a video of Frankie teaching to see how he did this stuff:

Frankie Manning’s Class part 2

I don’t think his approach is 100% excellent. He does drive the class, he uses gendered language, etc etc. But he is the ‘star’ teacher, and his teaching partner partner is his assistant – this is very clear. He uses gendered language because he is explicitly thinking about male leads and female follows, and his talk about respectful dancing uses this gendered dichotomy. I’m not excusing this, I’m pointing it out. And here I can make this point: while I dig a lot of what Frankie is doing in this video, he’s not perfect, and I actually find that reassuring. He wasn’t a saint, he was a real person, and when we idolise dancers, we need to keep that in mind: we don’t excuse their faults because we love their dancing.

A couple of things I like about this class:

at about 4.44: “If you find yourself falling, and he does not stop you from falling…. take him with you.” I LOLed when I heard this. But it’s a nice, simple way of saying ‘look out for each other!’ and reminding women that they aren’t passive objects here.

11.48: Frankie tackles inappropriate contact “Fellas, don’t take advantage…. we are just dancin’”

Nuff said, really.

With all this talk about Frankie, I think it’s worth pointing out:

When you watch footage of younger Frankie (ie in his 60s, and 20s), he seems quite ‘rough’ or ‘strong’ compared to modern dancers. Is this in conflict with this ethos of mutual respect in lindy hop?

(photo credit: I found this pic via an image search on google, and it’s hosted by Swungover, but chrome crashed and I couldn’t find the page again! argh! So I don’t know who the photographer is!)

This is a tricky one, but I think it’s where we’re really done a disservice by the lack of attention to the original women lindy hoppers who danced with Frankie teaching us today. I suspect that women followers were a different breed too. When you watch historic footage, you see that they fiercely took space, and matched their partner’s intensity. So Frankie might have had a partner who was confident enough to take space, and to be a little less submissive and a little more determined to shine.

I have no evidence for this, and it probably reveals my own lack of dance knowledge and skill. But I’m wondering if we need to have a look at old footage in a new way. I’m thinking of the way Janice Wilson used to talk about Ann Johnson, and the fierceness of her swivels. And of course, you have to think of Norma Miller when you think about fierce women lindy hoppers.

At any rate, this brings us back to the idea of how we might use history when we talk about lindy hop partnerships. And I have no real, final answers, of course, just a bunch of poorly practiced ideas.

Heroes Of Jazz and other Visible Mythologies

(photo by Andy Friedman from The Nation article linked below)

There was an interesting (and particularly stroppy) discussion about the ‘lindy hop career’ on the Jive Junction facebook page a little while ago that I keep thinking about.

I have real problems with stories about jazz music and jazz dance (both historical and contemporary) that present it as a series of stories about heroic figures. Particularly heroic men. Who aren’t burdened by caring for children or partners. Or otherwise engaged with their local communities.

I get really shitty about this approach because it ignores all the other labour that makes art possible: cooking meals, earning money, cleaning houses, paying for doctors, networking with venue managers, agents, producers, and recording record labels, etc etc etc. And it ignores all the ways in which artists are engaged with and participate in their local communities, and how all these relationships shape their creative work.

This was something that the Ken Burns Jazz documentary did, and which I’ve written about a bunch of times, in posts like:

- Lists and Canons in Jazz

- The trouble with linear jazz narratives + more

- Valuing the process rather the product

- Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong

- Magazines, jazz, masculinity, mess

I was reminded of this today by a quote-pic (don’t you hate those? Can’t search them!) getting about on twitter. This is the bit that interested me:

Frank Barat: You often talk about the importance of movements rather than individuals. How can we do that in a society that promotes individualism as a sacred concept?

Angela Davis: Even as Nelson Mandela always insisted that his accomplishments were collective—also achieved by the men and women who were his comrades—the media attempted to sanctify him as a heroic individual. A similar process has attempted to dissociate Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. from the vast numbers of women and men who constituted the very heart of the mid-twentieth-century US freedom movement. It is essential to resist the depiction of history as the work of heroic individuals in order for people today to recognize their potential agency as a part of an ever-expanding community of struggle.

I’m a bit of a fan of Angela Davis, and have written about her before in A long story about blues, women, feminism, and dance.

My policy on comments

Hello!

Once again, I’m getting a lot of traffic via discussions about gender and sexual assault and all that stuff.

So here is a reminder about my policies for commenting on this blog:

– if you post something upsetting, I will delete your comment

– if you play the feminist, not the ball (ie you attack me, not my ideas), your comment will be deleted

– if you fail to grasp the basic tenets of feminism, you comment will be deleted (you can do a bit of googling to figure out the basics)

– I will favour comments by women. Because.

etc etc

I’ve outlined my thinking about comments policies in this post, trollday. The upshot is that this is my blog, so I can do what I want. You don’t have a right to free speech here; this is a feminist space, and I am the boss of it. If you disagree or want to argue or rant, get your own blog.

Why did I get so strict? Because I CAN! I CAN!

And because I routinely get horrid comments and emails from randoms who want to school me.

Note: I will not hesitate to report your arse to the police. And please remember: anonymity is not that easy on the internet; we can discover who you are via your ISP, etc etc. And I will not tolerate bullying in MY space.

Total bullshit

All you need to know about the ‘learning styles’ myth.

Two other myths that shit me: ‘right brain/left brain’ and ‘muscle memory’. The second is particularly irritating. Your muscles do not have memory. They are _muscles_, not brains. So when you are learning a new dance step (for example) you don’t repeat it a heap of times to fix it in your ‘muscle memory’. You repeat it a million times* to improve fitness, balance (core stability), even to make your muscles stronger. But they don’t remember anything. Your brain does that.

*We could also argue that repeating anything a million times without some degree of mindfulness** isn’t terribly helpful. Like those jocks in the gym using momentum to lug weights into the air, rather than recruiting the right muscles, you can do something a million times and still not be achieving your goals.

**By mindfulness, of course, I mean an awareness of what you are doing with your body in that moment. And by awareness I mean knowledgeable awareness.

Josephine Baker

An issue of Scholar & Feminist Online devoted to Josephine Baker: Josephine Baker: a Century in the Spotlight, edited by Kaiama L. Glover.

Chorus lines and women dancers

Plenty of Good Women Dancers exhibition

This Philadelphia Folklore Project exhibition is fantastic.

Note to self: chase down Lee Ellen Friedland’s latest work, as her project on tap dancers in Philadelphia was so important to my own work. And apparently she’s done work on jewish folk dances, which is important for talk about NOLA music and dance. And this exhibit’s host is based in Philadelphia.

NB I don’t have to explain why this exhibit is important, do I? Ok, I will anyway.

1) Women dancers. BOOM.

2) Chorus line projects are tres chic in the lindy hop world. The most interesting one I’ve seen so far is Marie N’Diaye’s project in Stockholm, where they’re based in the Chicago studio, and perform at Herrang, week in and week out. I had no idea just how intense and hardcore this project is until I saw Marie’s footage and spoke to her about their training and choreographing work load. This shit is intense.

3) A lot of the biggest name women dancers began in chorus lines. Josephine Baker. Marie Bryant. etc etc etc.

4) These women dancers were insanely fit and strong. They would be performing multiple times during the day, learning new routine every week, singing, dancing, tapping, jazzing, etc etc etc. These were dancing machines. And yet they were often dismissed as bits of fluff.

5) Managing chorus lines was a way for women dancers to participate in the entertainment industry as professionals with serious industry power.

6) Running chorus lines today is just as important for women dancers now as it was then: women working together, running serious projects, training bloody hard, learning to choreograph, run a troupe and dance business, generally be awesome.

7) Being in a chorus line is hard work, and a way for modern women dancers to get mad skills: fitness, strength, memory, quick learning skills, choreography, etc etc etc.

8) Chorus lines are a way for modern women dancers to sidestep the bullshit power politics of dancing and competing with male partners in the lindy hop world. And yet still get mad dance skills that improve their lindy hop.

Another shit-stirrer post about teaching

I’ve been thinking quite a bit lately about why people teach, and what they get out of it (for obvious reasons).

There is this idea in the lindy hop world that we should all sacrifice lots ‘for the community’. As though ‘the community’ was this really huge thing, larger and more important than all of us, and yet somehow not including us at all. I’m not sure where this idea that we should sacrifice our own health and spare time for the sake of other people’s dancing came from. I sometimes think it has to do with the revivalist impetus: that we have to keep lindy hop alive no matter what. Which is problematic for so many reasons. Starting with a) It wasn’t actually dead before busy white people started getting into it in the 1980s; b) If the communities that developed it have moved on to other things, perhaps a vernacular dance has lost its utility, and social dances should be useful and relevant above all else.

This is what I think:

- communities must be sustainable. Culturally, socially, economically, environmentally… and so on.

- The people in the community are that community. That includes the teachers and volunteers and event organisers and so on… all the people who are working their bums off to ‘keep the dance alive’. This means that their lives and work have to be sustainable: they have to earn enough money to pay their bills; they can’t ruin their health and relationships and lives with overwork; they have to find joy their work – it cannot be a burden. ie NO MARTYRS.

- The ‘community’ is not a discrete bubble. All ‘communities’ overlap and interact with other ‘communities’. So the ‘lindy hop community’ is also a part of, or overlapping with, the ‘jazz community’, and the ‘vintage lifestyle’ community, and the ‘live music industry’, and the ‘wider local community’, and the ‘national community’, and so on. We are no better or worse than the people who don’t dance lindy hop. Lindy hop doesn’t make us special; we are already special. And so are the people who don’t dance lindy hop.

I know that a lot of lindy hop teachers I’ve met and worked with in Sydney and Melbourne feel as though the value of their teaching is assessed by the number of students in their class. As though they somehow fail to be good or important or useful teachers if they aren’t funnelling hundreds of new lindy hoppers onto the floor every year. I used to feel this way. But now I don’t.

I think that we all realise that huge classes are not good learning or teaching environments. Students don’t get the time or attention they need from teachers, nor do they develop the social bonds that help make a good community. Their learning and sense of ‘group’ is focussed on the teacher, and often, on the larger school identity. Rather than on the smaller, more important relationships with other people in their class, and on the social dance floor. Further, classes that focus on rote learning, on running through a sequence of steps over and over again until the students have it ‘perfect’ is not great learning.

It’s as though this sort of class deliberately undoes the culture and practice of social dancing. If you are pushing through a rote sequence of steps, no matter what, you cannot stop and listen to your partner, you cannot adjust your dancing to work with your partner and make it work, and you definitely cannot listen to and respond to the music. And that is very sad. It is also the opposite of lindy hop: this is not preserving a vernacular dance.

I see students come out of dance classes unable to ‘start’ dancing on the social dance floor until someone ‘counts them in’ or helps them ‘find one’. As though there was this rule that we HAVE to start dancing ‘on one’, or that steps have to perfectly align with an 8 or 6 count sequence. More importantly, those same students haven’t learnt how to make a real connection with a dance partner, because their attention in class is so focussed on the teachers; they’ve never learnt that it’s ok to just bop about on the spot with a new friend, chatting, and enjoying the music. They feel that they have to execute that series of prescribed moves perfectly if they are to be ‘good dancers’. And of course, those prescribed moves are only available (for a price) from a dance class.

This isn’t the students’ fault. Or even the teachers’, really. It’s the fault of a pervasive ideology of ‘learning through memorisation’, and a push to acquire huge class numbers as an indicator of ‘success’ – primarily financial. It’s also accepted that the retention rate of any class will be low – that people will find lindy hop really hard in their first class, and that they won’t ever come back. And, to be blunt (as though I was ever anything else), I’d be scared off by a huge class focussed on rote-learning a series of strictly ‘perfect’ steps.

The saddest thing about all this, is that this is not what lindy hop – or jazz – is all about. It makes me sad that teachers feel they have to push their classes to become bigger and more ‘successful’, instead of taking time to enjoy the time they spend with students in class. They are so intent on acquiring the ‘sexiest’, most ‘sellable’ steps from the latest round of competition videos, that they forget that dancing is actually lots of fun, particularly when the steps are simple and the focus is on the music and your partner.

I’ve recently shifted my own focus – in a very determined way – to classes which are all about social dancing. That means great music. That means learning to work with a partner – and not just for a 30 second rotation in class, but for a whole song in class. I don’t teach fixed patterns of steps; I teach a pattern, and then build on it, encouraging the students to figure out their own combinations. With Marie and Lennart’s example in mind, after the first few partner rotations in class, I don’t ‘count students in’ any more. I let them find their own way into the music. To me, these are the real skills social dancers – lindy hoppers – need. Nobody needs that latest trick that Famous Dancer X pulled out in a comp. A competition is not social dancing; the skills are quite different.

The nicest part of this shift in focus is that I find teaching so much more satisfying, and so much less anxiety-making.

So why am I writing this post now? It’s because this story about Stefan Grimm has been making the rounds in my academic network. I used to work in academia, but gave it up because it just wasn’t any fun. The students were neglected by shitty class environments, the research wasn’t fun any more because it was squeezed into restrictive grant-getting processes.

Reading this piece about universities as anxiety machines, I was struck by the similarities between the ‘dance class industry’ and universities. And not just because they’re both centred on pedagogy (or are they? What university still prioritises learning – whether through research or teaching?) The discussion about unpaid labour (normalised by the idea that ‘that’s what you do to get ahead’), sounds a lot like the exhaustion and exploitation in the lindy hop world justified by ‘doing it for the community’. The

…normalised surveillance of performance in class through attendance monitoring, learning analytics, retention dashboards and text-based reminders about work/labour/doing, and in the entrepreneurial demands of attending careers fairs and employability workshops and cv clinics, and in attempting to find the money to eat and live.

…sounds a lot like lindy hop today.

Get bigger classes. Where are you on the leader board? Have you hunted down the latest marketable step or move from the latest round of competition videos on Youtube? Did you go to that workshop and ‘collect’ moves?

And for ‘professional’ lindy hoppers (as though we aren’t professional unless we are traveling the world every weekend), the pressure is far higher. Not teaching on a repetitive injury? Not working hard enough. Not disguising disordered eating as ‘eating healthy’, ‘the paleo lifestyle’, or, most ironic of all, ‘keeping well’? Not truly committed to dance. Haven’t taken up a dozen ‘strength and maintenance’ exercise regimes on top of your lindy hop training? Just aren’t trying hard enough.

…this form of overwork and performance anxiety is a culturally acceptable self-harming activity. …My culturally acceptable self-harming activities militate against solidarity and co-operation that is beyond value…

(all these quotes are from ‘Notes on the University as anxiety machine’)

This is, of course, the bottom line. Because teachers (especially the highest profile ones) don’t spend quality time with anyone other than other teachers for extended periods of time, this stuff is all normalised. And they aren’t allowed the time and quiet to question the working conditions of their ‘jobs’. They are expected to work and work and work ‘for the community’. And if they do ask event organisers for things like, oh, a quiet room with a door that closes and a real bed to sleep, there is this niggling perception of them as ‘difficult’.

I don’t know where I’m going with this, really. Beyond arguing that we should shift our focus to more socially sustainable practices. And we should question the ‘for the community’ ethos that justifies socially and physically unsustainable work practices. Also, we should teach lindy hop like a vernacular dance, not like you’re going to be sitting an SAT test.