Today I was talking to someone completely unconnected to the dance world, and they asked what I’d been doing lately. I mentioned that I’d been been working on a covid policy, and it was really interesting because it was a way to talk about flatter power structures (and fighting The Man). I wanted to do more than just present a bunch of rules and then enforce them authoritarian style.

I mentioned that masking is a good option, but it’s rubbish for dancing in.

Then I mentioned that vaccination is really important, but that only 69% of NSW people have had more than two covid vaccinations.

My friend had been active listening along, but when we go to this point, they were clearly quite flushed and emotional. So I stopped yapping. They told me that they were really tired of the covid stuff, and had two vaccinations, but that “Other people can get more.” They went on to talk about how the lockdowns and government policies had really exhausted them, and the lack of gov support had taken a toll on their business. Their major concern was with the way the vaccines are produced by corporations of dubious ethics and morality.

I nodded and did active listening. They were upset and needed to talk about these things. And these are reasonable concerns: lack of support from a government that enforced unjust limits and penalties does not inspire compliance. And as Aboriginal communities can explain, an unjust government cannot be trusted with your medical data, let alone your body in a medical setting. Nor can we excuse the way big corporations in the medical industry have conducted itself in the past, or in the production and dissemination of vaccines (particularly in developing countries).

I didn’t once say that my friend should get a vaccination. That’s not cool; we don’t make medical decisions for other people like that.

As we continued talking, I shifted things away from vaccination to the frustrations with the government policies. They had interesting things to say about that. At one point I mentioned that the whole point of this particular covid policy was to do good social activism. And part of that was discussing equity. So if we have a ‘must test’ policy, we also need to make RATs freely available, because they’re expensive, and they’re a barrier to participation for people who can’t afford them (and who are also often in those high-risk workplaces). Then I pointed out that if I was going to do a policy that was just, I had to source free masks and RATs. And I explained how I’d done that.

It was interesting to see friend’s reaction to this information. Getting free stuff from The Man is always a pleasure, and it seemed to delight my friend.

I wonder if masks would get the same response? Perhaps not, as wearing them is a lot less fun than getting a covid test :D :D

But this conversation made some things very clear to me. If we simply make rules and then penalise people for not following them, we destroy their trust in us, and we make them pretty bloody shitty. A better alternative is to ‘call in’ (rather than ‘calling out’), and make it easy for people to make their own educated decisions about their health.

If we want people to do something (or things), then we can do better than just telling them what to do. We can provide information, and then let them decide what to do with their own bodies.

In the case of something like a pandemic, we can frame this discussion as one of mutual care, where you get vaccinated, wear a mask, wash your hands, or whatever not necessarily for your own benefit, but for the safety of others. And they do the same for you.

This is very effective for people who have a communitarian impulse. But what if they don’t?

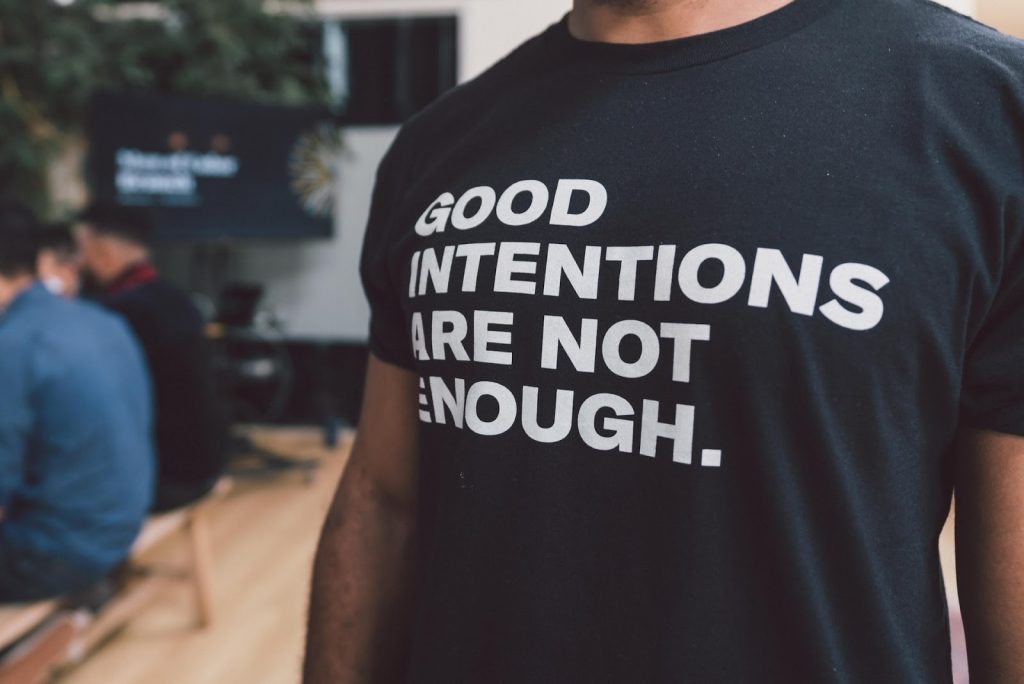

As I discovered with my friend, there are other inducements we can offer. Or rather, we can find the side of the issue that appeals to them. We can frame the discussion as one of civil disobedience, or evading punitive rules. Accessing tests can become a mission of getting free shit and evading the capitalist structures of ‘big pharma’. Similarly, making or accessing masks that work as a billboard for a person’s politics (much like a Tshirt) can be a way of encouraging people to wear a mask.

And we were both on board with the idea that not washing your hands after you use the bathroom is fucking rotten. :D :D

So when it comes to communicating your policy, it helps to:

- Use language, imagery, and framing that appeals to their values (be they communitarian, radical feminist socialist, or anarchist), and

- Use a variety of approaches to reach a variety of people.

The dance world, of course, is made up of a whole mass of interconnected hyper-local communities that are part of an international, intercultural global community. Even a single local scene in one city might be comprised of a few smaller micro-communities, each centered on a dance school, a particular social night, or a performance troupe. Each of these has its own specific culture and social norms. And we know what each of these are like, because we are part of them. After all, it’s hard to be a lindy hopper if you don’t actually lindy hop.

If we are actually observant humans, we understand that our own experience of a group or community is not the same as someone else’s. For example, you might have loved learning to swing out using lots of technical jargon, but your friend might have loved learning-by-doing. And you might love the late night parties that start at midnight because you’re single with no kids, but your friend might prefer afternoon dances that are child-friendly, because they’re a parent.

We might be aiming for diversity in many places, but we often just don’t get there. Students tend to be people ‘like’ their teachers (same demographics, same sense of humour, same values, etc). Performance troupes tend to be a similar age, physical fitness, and schedule. Paying for classes excludes people on low-incomes, so people in classes have disposable incomes. And so on. It’s actually good that a single scene is made up of lots of different types of mini-groups. So long as they can all come together with kindness and a generosity of spirit for things like bigger parties, events, and discussions.

This is why I think it’s very, very important for each of these micro-groups to develop their own covid policies, ones that speak the right language, carry the right values, and ultimately change people’s behaviour. Or in the case of my own commitment to ‘radical care’, a policy that actively contributes to social justice and fighting the fucking man.

Some facts about masks

The one good thing about respirator masks (P2 or N95) is that they can be used more than once, provided you handle them carefully (no touchy!) and let them dry out properly before re-using.

If you’re curious, a well-fitted surgical mask will do in a pinch, but they cannot be re-used, and you need to fit it properly. Which applies to all masks, really.

And unlike some places in the US, in NSW you can deny entry to people who aren’t wearing masks.

The rules in Victoria are slightly different (check the info site here). They make exception for professional sports people (no, lindy hopper, you are not a professional sports person if you are a student in a class). They do, however, make it clear that if you can’t do social distancing, you’re indoors, and you’re with more than 2 or 3 people, you should mask.

Types of masks is an interesting one. While the science suggests that P2 or N95 masks (fitted and worn correctly) are the only options, we know that most people don’t fit or wear any masks correctly, so no mask is really going to stop the transmission of covid. But we also know that wearing masks can remind people to distance, and can signal to other people that the wearer is concerned about covid.

My personal policy is: mask! Always! indoors and in crowds outdoors, and I always use a P2 or N9, fit them properly and never touch them.

My feeling for a public covid policy, is that we strongly recommend masks (the right types – P2 or N9 and surgical), make them freely available, have influential people (teachers, DJs, performers) model wearing them, but we definitely begin or stop there. We place equal emphasis on vaccination mandates, hygiene, testing regularly, symptom checking, and staying home if you have symptoms, test positive, or are a close contact.

Some facts about RATs and PCR tests

(Please note: this information can change very quickly. It did in the couple of days I was researching this topic! So always double check. And some centers run out of RATs, so double check)

Free RATs were provided by the federal government up until this week. But now the state governments (in Vic and NSW at least) have stepped in to provide them. Free RATs are available to some concession card holders:

Eligible Commonwealth concession card holders can access free rapid antigen tests through the concessional access program. Up to 20 rapid antigen tests are available for free for eligible people living with a disability at state-run testing sites and through Disability Liaison Officers. Eligible people include NDIS participants, disability support pensioners and people with a disability who receive a TAC benefit. Evidence of eligibility, such as an NDIS or TAC statement, is required (source).

Anyone can collect 5 rapid antigen tests (per person) from a COVID-19 testing site in Victoria (source).

In NSW, RATs are free to some concession card holders, and available at neighbourhood centers and NDIS providers. I can’t find information about free RATs for anyone else, though word of mouth suggests you can get them if you ask.

And of course, PCR tests are still free, and available at testing clinics. Though these tests are more reliable than RATs (because they’re conducted by pros, not you with a jumbo q-tip in your bathroom), the results can take up to 48 hours (though they’re usually with you within 24 hours).

Some facts about vaccines

Vaccines are the best way to contain covid at this time, in developed countries like Australia. They prevent you getting really sick, and they stop you spreading the virus to more vulnerable people (because you’re not as sick you don’t blow droplets everywhere as much, and because you’re not sick for as long, you spend less time blowing droplets everywhere).

But they only last for about six months. Which is why we need to get boosters every six months.

If you do catch covid, your immunity only lasts for about three months after your symptoms end (source). Which is why you can get it over and over again in one season.

You can get vaccinated when you’re pregnant or breastfeeding, and it’s recommended. And a note about the magic of breastfeeding: your milk contains antibodies that are given to your babby, giving them immunity! Hoorah for boobs.

Vaccination is free in Australia, and you can get a quick vax from your local chemist, a GP, or a covid center (do check your state’s local vaccination centers, but you can search nationally here.) I got mine at my local chemist. I just walked in and said “Can I get a covid vaccine, please?” and they did it then, and there, then a bit later it was in my digital vaccination certificate on the Services NSW app on my phone. No mess, no fuss.