Here’s a post I’ve just discovered, that may have fallen off my database somehow.

MAY 4, 2009

In the earliest parts of my researching into jazz history, I tried to set up a sort of ‘time line’ or map* of musicians and cities and bands. Who played with which band in what city at what time? Then where did they go? This approach was partly based on the idea that particularly influential musicians (like Armstrong) would spread influence, from New Orleans to New York and beyond.

But drawing these time lines out on pieces of paper, I found it wasn’t possible to draw a nice, clear line from New Orleans to New York, passing through particular bands. Musicians left New Orleans, went to New York, then back to New Orleans, then off to France, then back again to New York. The discographies revealed the fact that a band recorded in different cities during the year – they were in constant motion, all over America. Furthermore, musicians didn’t stick with one band, they moved between bands, they regularly used pseudonyms and even the term ‘band’ is problematic. The Mills Blue Rhythm Band, with its dozens and dozens of names, was in fact a shifting, changing association of musicians, and did not even have a fixed ‘core’ set of players. Perhaps this is why the MBRB is so important: many people played with them, and they were a band(s) which moved and changed shape, a loose network of musicians who really only existed as ‘a band’ when they were caught, in one moment, on a recording. Or perhaps on a stage (though that’s far more problematic). I wonder if that’s why it’s so hard to find a photo of them? Perhaps the ‘Mills Blue Rhythm Band’, as a discrete entity didn’t really exist?

The more I read about jazz and ‘jazz’ history, the more convinced I am by the idea of ‘jazz’ as a shifting series of relationships. I think about cities not as fixed locations, but as points on a sort of ‘trade route’ or even as a complicated web or network of relationships between individual musicians (which is, incidentally, how I think about international swing dance culture – the physical place is important, but it’s not binding).

Right now I’ve followed some references backwards to an article by Scott DeVeaux called Constructing the Jazz Tradition, which is really interesting. It not only outlines some of the political effects of a coherent ‘narrative’ history of jazz, but also the economic and social effects of positioning jazz as a ‘black music’, with interesting references to consequences of the ‘jazz musician as artist’ for black musicians. Read in concert with David Ake’s discussion of creole identity and ethnicity in New Orleans as far more complicated than ‘black’ and ‘white’, this makes for some pretty powerful thinking.

I’m very interested in the idea of a ‘jazz canon’ and of the role of people like Wynton Marsalis, the Ken Burns Jazz discography, jazz clubs and magazines developing during the 30s and 40s devoted to New Orleans recreationism and the whole ‘moldy figs’ discussion. The tensions surrounding the Newport jazz festival also feed into this: the Gennari article (which I discuss in reference to its descriptions of white, middle class men rioting at Newport here) pointed out the significance of a festival program loaded with ‘trad’ jazz – for black musicians and for the popularising of jazz generally. I’ve also been reading about the effects of this emphasis on trad jazz for superstar musicians like Louis Armstrong.

O’Meally and Gabbard have written about the way Armstrong’s public, visual persona is marked by ethnicity.

Armstrong was known for his visual ‘mugging’, or playing the ‘Uncle Tom‘ for white audiences, particularly on stage. Eschen writes

…as the struggle for equality accelerated, Armstrong was widely criticized as an Uncle Tom and, for many, compared unfavourably with a younger, more militant group of jazz musicians (193)

This, as Eschen continues, despite the fact that Armstrong was actually an active campaigner for civil rights in America, and overseas.

The trad jazz movement – or ‘moldy figs’ pushing for the preservation of an ‘authentic’ jazz from New Orleans – effectively pushes Armstrong to continue as Uncle Tom – unthreatening black man clowning for white audiences. A narrative history of jazz which emphasises a beginning in New Orleans and a consistent, clearly defined lineage of musicians and styles also, more subtly, relies on an idea of the black musician as powerless or unthreatening. DeVeaux makes the point that positioning jazz (and jazz musicians) as artistic loners who do not ‘sell out’ with commercial success:

Issues of ethnicity and economics define jazz as an oppositional discourse: the music of an oppressed minority culture, tainted by its association with commercial entertainment in a society that reserves its greatest respect for art that is carefully removed from daily life (530)

In this world, the ‘true’ jazz musician is ‘black’ (in a truly singular, homogenous sense of the world), he is poor and he is mugging for white audiences.

Billie Holiday becomes a particularly attractive representation for this idea of the ‘jazz musician’: poor, black, addled by drugs and alcohol, a history of prostitution, yet nonetheless, a creative genius pouring out, untainted in recording sessions (and I’m reminded of the ‘one take’ stories) and tragically cut short.

All of this is quite disturbing for someone who really, really likes jazz from the 20s, 30s and 40s. Am I buying into this disturbing jazz mythology? It’s even more disturbing for someone who found similar themes in contemporary swing dancers’ development of ‘narratives’ and geneologies of jazz dance history. As DeVeaux writes (about jazz, not dance), though, this is

The struggle is over possession of that history, and the legitimacy that it confers. More precisely, the struggle is over the act of definition that is presumed to lie at the history’s core (528)

I wonder if I should suspect my own critique of capitalist impulses in contemporary swing dance discourse?

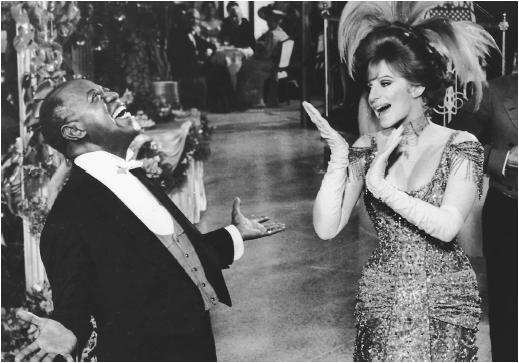

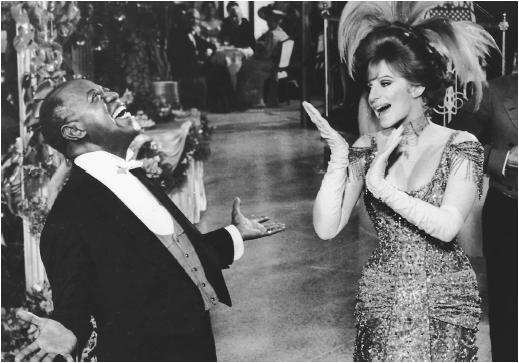

I don’t think it’s that simple. Gabbard discusses Armstrong’s work with Duke Ellington, including the filming of Paris Blues (in which Armstrong starred, and for which Ellington contributed the score) and the recording of the ‘Summit’ sessions:

I don’t think it’s that simple. Gabbard discusses Armstrong’s work with Duke Ellington, including the filming of Paris Blues (in which Armstrong starred, and for which Ellington contributed the score) and the recording of the ‘Summit’ sessions:

at those moments in the film when he seems most eager to please with his vocal performances, his mugging is sufficiently exaggerated to suggest and ulterior motive. Lester Bowie has suggested that Armstrong is essentially slipping a little poison into the coffee of those who think they are watching a harmless darkie.Throughout his career in films, Armstrong continued to subvert received notions of African American identity, signifying on the camera while creating a style of trumpet performance that was virile, erotic, dramatic, and playful. No other black entertainer of Armstrong’s generation “with the possible exception of Ellington” brought so much intensity and charisma to his performances. But because Armstrong did not change his masculine presentation after the 1920s, many of his gestures became obsolete and lost their revolutionary edge. For many black and white Americans in the 1950s and 1960s, he was an embarrassment. In the early days of the twenty-first century, when Armstrong is regularly cast as a heroicized figure in the increasingly heroicising narrative of jazz history, we should remember that he was regularly asked to play the buffoon when he appeared on films and television (Gabbard 298)

You can see a clip from Paris Blues here.

Armstrong’s performance gains meaning from its context, from the point of view of the observer, from his own actions as a ‘real’ person (Armstrong was in fact openly, assertively critical of Jim Crowism and quite politically active) and from its position within a broader ‘body’ of Armstrong’s work as a public performer. Pinning it down is difficult – it’s slippery.

The idea of layers of meaning is not only interesting, it’s essential. This physical performance of identity, tied to the physicality of playing an instrument reminds me of the layers of meaning in black dance. And of course, of hot and cool in dance, and the layers of meaning in blues dance and music. Put simply, what you see at first glance, is not all that you are getting. Layers of meaning are available to the experienced, inquiring eye. Hiding ‘true’ meanings (or more subversive subtexts) is important when the body under inspection is singing or dancing from the margins. Tommy DeFrantz discusses meaning and masculinity in black dance during slavery:

serious dancing went underground, and dances which carried significant aesthetic information became disguised or hidden from public view. For white audiences, the black man’s dancing body came to carry only the information on its surface (DeFrantz 107).

Armstrong’s performance is more than simply its surface. As with any clown, the meanings are more complex than a little light entertainment. Gabbard continues his point:

In short, Ellington plays the dignified leader and Armstrong plays the trickster. Armstrong’s tricksterisms were an essential part of his performance persona. On one level, Armstrong’s grinning, mugging, and exaggerated body language made him a much more congenial presence, especially to racist audiences who might otherwise have found so confident a performer to be disturbing, to say the least. When Armstrong put his trumpet to his lips, however, he was all business. The servile gestures disappeared as he held his trumpet erect and flaunted his virtuosity, power, and imagination (Gabbard 298).

This, of course, reminds me of that solo in High Society that I mentioned in a previous post. There’s some literature discussing the physicality of jazz musician’s performances, but I haven’t gotten to that yet (though you know I’m busting for it). I have read some bits and pieces about gender and performance on stage (especially in reference to Lester Young), and there’re some interesting bits and pieces about trumpets and their semiotic weight, but I haven’t gotten to that yet, either.

Sorry to end this so abruptly: these are really just ideas in process. :D

To sum all that up:

– The idea of a jazz musician as ‘isolated artist’ is problematic, especially in the context of ethnicity and class. Basically, the ‘true jazz musician who doesn’t sell out by making money’ is bad news for black musicians: it perpetuates marginalisation, not only economically, but also discursively, by devaluing the contributions of black musicians who are interested in making a living from their music. Jazz musicians are also members of communities.

– Linear histories of jazz are problematic: they deny the diversity of jazz today, and its past. Linear histories with their roots in New Orleans, insisting that this is ‘black music’ overlook the ethnic diversity of New Orleans in that moment: two categories of ‘black’ and ‘white’ do not recognise the diversity of Creole musicality, of the wide range of migrant musicians, of the diversity within a ‘white’ culture (which is also Italian and English and American and French and….), of economic and class relations in the city, and so on.

– ‘linear histories’ + ‘musician as artist’ neglect the complexities of everyday life within communities, and the role that music plays therein. These myths also overlook the fact that music is not divorced from everyday life; it is part of a continuum of creative production (to paraphrase LeeEllen Friedland and to refer to discussions about Ralph Ellison – which I will talk about later on).

– Music and dance have a lot in common. They carry layers of meaning, and aren’t simply discrete canvases revealing one, singular meaning to each reader. They are weighted down by, buoyed up by a plethora of ideas and themes and creative industrial practices and sparks.

DeFrantz, Thomas. “The Black Male Body in Concert Dance.” Moving Words: Re- Writing Dance. Ed. Gay Morris. London and New York: Routledge, 1996. 107 – 20.

DeVeaux, Scott, “Constructing the Jazz Tradition: Jazz Historiography” Black American Literature Forum 25.3 (1991): 525-560.

Eschen, Penny M. The real ambassadors. Uptown Conversation: the new Jazz studies, ed. Robert O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, Farah Jasmin Griffin. Columbia U Press, NY: 2004. 189-203.

Friedland, LeeEllen. “Social Commentary in African-American Movement Performance.”

Human Action Signs in Cultural Context: The Visible and the Invisible in

Movement and Dance. Ed. Brenda Farnell. London: Scarecrow Press, 1995. 136 –

57.

Gabbard, Krin. “Paris Blues: Ellington, Armstrong, and Saying It with Music”. Uptown Conversation: the new Jazz studies, ed. Robert O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, Farah Jasmin Griffin. Columbia U Press, NY: 2004. 297-311.

Gennari, John. “Hipsters, Bluebloods, Rebels, and Hooligans: the Cultural Politics of the Newport Jazz Festival.” Uptown Conversation: the new Jazz studies, ed. Robert O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, Farah Jasmin Griffin. Columbia U Press, NY: 2004. 126-149.

Lipsitz, George. “Songs of the Unsung: The Darby Hicks History of Jazz,” Uptown Conversation: the new Jazz studies, ed. Robert O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, Farah Jasmin Griffin. Columbia U Press, NY: 2004: 9-26.

O’Meally, Robert G. “Checking our Balances: Louis Armstrong, Ralph Ellison and Betty Boop”. Uptown Conversation: the new Jazz studies, ed. Robert O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, Farah Jasmin Griffin. Columbia U Press, NY: 2004. 276-296. (You can see the animated Betty Boop/Armstrong film O’Meally references here.

*The jazz map was found via jazz.com, but they don’t list the url for the map in context.

There’s something seriously addictive about historic ‘jazz maps’. I think it’s because they’re imaginary places. My latest find: New Orleans ‘jazz neighbourhoods’.

I don’t think it’s that simple. Gabbard discusses Armstrong’s work with Duke Ellington, including the filming of Paris Blues (in which Armstrong starred, and for which Ellington contributed the score) and the recording of the ‘Summit’ sessions:

I don’t think it’s that simple. Gabbard discusses Armstrong’s work with Duke Ellington, including the filming of Paris Blues (in which Armstrong starred, and for which Ellington contributed the score) and the recording of the ‘Summit’ sessions: