(tent image from here, police image from here)

I’m really interested in the discussion of official versus community policing of public space in Chris Brown’s article ‘The Occupy Movement and the Battle for Public Space’. One point I took from this was Brown’s juxtaposition of the formal, highly ordered occupation of public space by the police and ‘official’ entities with the informal, collaborative and negotiated management of public space by community groups. I think that both types of management of public space happen in all sorts of communities, and that they’re really just two points on a broad spectrum of behaviours. I want to spend the rest of this post taking this idea and applying it to dance competitions. Competitions which can be at once ‘officially’ managed public spaces and also collaborative or informally managed public spaces. At the same time!

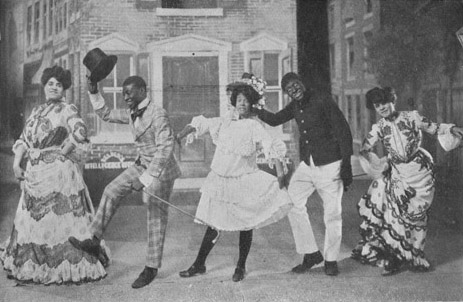

I’ve always been interested in the way dancers regulate the social dance floor (which I’ve always thought of as ‘public space’ or public discourse). One of my favourite topics is derision dance. Or using dance to deride someone (using the dictionary definition “contemptuous ridicule or mockery”). This can be as simple as directing a crude gesture to your opponent, but it is often more complex, involving layers of imitation, impersonation and subtler mockery. This last type is what really fascinates me. I wrote about derision dance and layers of meaning in what again?! I’m still crapping on about dance, power, etc; I used derision as a tool for understanding blackface in blackfaces and performing identity. again. (again using the idea of layers); and I talked about cake walk as an example of derision in hot and cool.

I keep coming back to the idea of dance as a forum or tool for deriding or subverting authority or an opponent because it’s a contribution to public discourse which doesn’t use words. I get a bit frustrated with work on public discourse which prioritises the written word, as there are all sorts of dodgyarse power dynamics happening there. Not all of us have literacy and linguistic competency on our side; class and race and ethnicity are pretty important factors here.

Of course, I’m not alone in talking about bodies in public space. That’s why I like that Chris Brown article. It describes the way non-verbal occupation of public space is regulated by official and community powers. When I think about dancers regulating the public space of the dance floor, I think about official ‘laws’ or guidelines like a sign forbidding aerials in a particular room for safety or heritage-building reasons. Or a more experienced or authoritative dancer telling an idiot lead to stop tossing follows into the air. But I’m also quite interested in the unspoken, unofficial and less overt management of public space in dance communities. It’s a little too far along the spectrum to ‘official’ to really illustrate my thoughts, but I want to begin with (and probably end with – as I’m off to the beach in a tick) dance competitions.

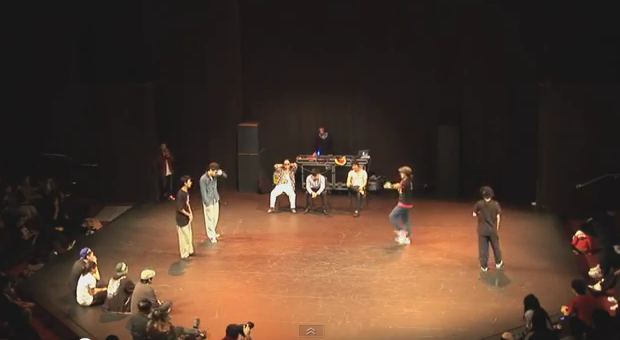

I’ve just been watching this clip from the studio we use of ‘The Crossover Popping Battle – Finals’:

There are all sorts of cool things to say about the way the studio uses Youtube and faceplant, where I found the clip, and which is so central to the studio’s promotional and community development work. But I’m not going to do that here. I want to start with the dancing itself.

… suddenly, I’m realising that this might be beyond me right this second. I want to do a close textual analysis of what is happening on the dance floor. There’s lots to be said about the mise en scene of the film itself as well. I think this type of close analysis of the dance-as-public-text requires a certain about of specialised knowledge. If you can’t read bodies as a dancer, you can’t really understand the power plays. More specifically, if you can’t read popping, you can’t really understand who’s the more proficient dancer, the intertextual and historic references in each movement, the etiquette for this sort of battle type competition. To add a few extra layers of meaning, this is a battle hosted by one particular dance studio, so you’ll see institution-specific action and ideology at work here. Not to mention the fact that these kids are from all across Asia, speaking a number of different languages as well as English. I’m a white Anglo-celtic girl living in Sydney and I only speak English. I’m going to miss most of the more nuanced physical gestures and postural moments. So my analysis is really only a beginning place, and I couldn’t possibly see all the detail at work here, least of all because I’m not into popping.

This is a pretty important point. I can’t see all the regulation and management of this public place – this moment of discourse – at work here. So I’d be bound to make mistakes. But because I am a babby, I’d probably be excused quite a few mistakes. So long as my participation improved. These guys are really friendly and welcoming, and I know I’d be cut a fair bit of slack. But eventually, even the most tolerant teachers and peers lose patience with social ineptitude and rudeness in a public forum.

Interestingly, the dancers at this studio encourage new dancers to enter battles almost from the very beginning. I’ve sat in on a casual battle, and a lot of leeway is granted for new dancers. In contrast, there’s a real sense in Australian lindy hop that only the ‘best’ dancers enter competitions, unless the competitions are for ‘up and comers’ or ‘amateurs’. Of course, definitions of ‘best’ vary between cities, and don’t match up comparatively. And, really, the most successful dancers have a very strong sense of self worth and faith in their own abilities. They really believe they are – if not the best dancers – in with a shot at becoming the best. That’s just how competition works. If you don’t really believe you have a chance, you won’t work hard in preparation, you won’t devote time and effort to the project, and you won’t bring your A-game in the final moment.

So this means that we don’t see lindy hoppers developing performance and competition skills in a relaxed, welcoming and informal setting as very new dancers. I’ve noticed the dancers at Crossover develop a real sense of self-awareness and understanding of lines and visual presentation far earlier than most lindy hoppers. They work with mirrors right from the get-go. They spend a lot more time looking up and making eye contact (particularly in battles). In brief, ‘their movements go right to the end of their finger tips’, whereas a lot of lindy hoppers don’t even really know they have hands.

So, when you go to a battle with these guys, there’s rarely an explanation of the ‘rules’, beyond the very basics. This confused me when I first saw them in action. How was judging decided? How long did dancers have to perform? How did they decide who danced in what order? You’ll find rules for competitions on websites before the event, but mostly you just have to figure them out. And of course you won’t be in the competition if you haven’t at least acquired even that much cultural knowledge.

The same sort of thing happens with lindy hop competitions. Though most of the more popular recent comps have far more implied than stated rules. In fact, there was a conscious movement away from prescriptive rules in the US at some point in the early 2000s (I can’t really remember the details, sorry). Most Australian competitions followed this American trend largely as following a trend (rather than as a critical engagement with existing competition culture) a few years later. The exception is Hellzapoppin’, which was deliberately developed as a lindy hopper-run and regulated competition advertised as having ‘no rules’. Though of course it does have rules, and these are listed quite clearly.

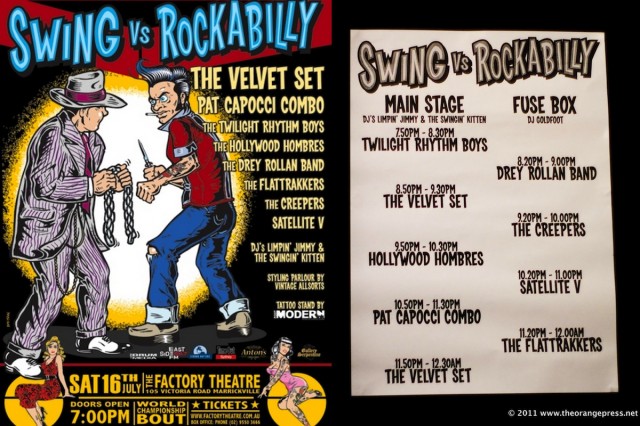

These rules are just a little different to other more prescriptive events like the ASDC and rock n roll or ballroom competitions. The inaugural Western Sydney Swing Dance Competition had quite strict, ballroom/rock r roll type rules, but I found it really difficult to discover much about the competition beyond this flyer. I ended up messaging the organisers on faceplant to find out more, then had a fairly long list of rules emailed to me as a pdf (which you can have a look at here). I found these rules really difficult to understand, in part because I’ve done very little competition, but also because I’m not a part of the rock n roll or ballroom dance scenes, which are far more tightly structured and formally organised than the lindy hop scene. I simply don’t have the language tools or cultural knowledge to navigate this sort of text.

The Crossover competition, though, is far more familiar. Rules for larger battles are often discussed in an informal way on faceplant, but more usually discussed in person. But learning the rules of competitions is more a matter of enculturation. The competitive space is as highly regulated as the WSDC, it’s just that the regulation is managed in a different way.

I’ve spent quite a bit of time in the past analysing lindy hop competition footage in close detail (‘lindy hop followers bring themSELVES to the dance; lindy hop leaders value this’ is probably the best example of how I approach this). It’s a very common practice for most lindy hoppers, and learning how to read dance (whether in footage or in person) is an ongoing process. Dancers are also on the lookout for different things. Leaders and followers often read a dance clip in quite different ways. I look for gender stuff. Someone else might be looking at shoe types. A DJ might be listening for new songs.

I’m going to get completely off-track here with a reference to a very famous dance clip.

This is a still from the Big Apple scene from Keep Punchin, featuring the Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers:

I’ve heard (second-hand, unfortunately), that Frankie Manning described this scene as a dance competition. In fact, the MC in the film introduces it as “The Big Apple contest”. Frankie explained that not only were couples competing against each other, but that individual partners were competing against each other. I’m not sure whether I’ve gotten that story right – it does come to be second-hand. But it’s an interesting idea. Competitors are working in pairs, focussing their performance on each other, as well as on those around them.

This is a bit like the Crossover battles (as far as I can tell – I’m not 100% sure about this next bit). In these battles competitors may enter as teams of two, but they dance alone, focussing their attentions on a particular member of the opposing team. There’s lots to say about focussed competition, and about how dancers in these battles turn their aggressive (yet never violent) competition on when they begin dancing, and then off when they move off the floor. I’m particularly fascinated by the way the non-dancing team member stands in a decidedly ‘I’m not dancing’ pose; they turn off their competitive dance energy, often by not making eye contact with their opponents. That’s some pretty basic non-threatening body language right there.

Right, back on-track, now…

It was quite interesting to see the new competition format for the Harlem 2011. Solo Jazz Contest held in Lithuania. It looks a lot more like the Crossover popping battle than other solo jazz comps in the lindy hop scene. How?

Firstly, here are some screenshots from those clips to illustrate my points:

(Harlem 2011, one of the rounds)

(Crossover popping battle, final)

- The three people sitting in the middle at the back are the three judges. We see this in the Crossover battle. They don’t write things down or discuss the competitors in detail, they just point to the dancer they think should win (or cross their arms to indicate indecision). In every other lindy hop competition the judges walk around the floor with clipboards, staring intently at competitors and writing things down before going out to another room to discuss the competition and arrive at a collaborative (or comparative) decision. Sometimes there’s an audience appreciation component. ULHS has a very strong audience appreciation component.

- Competitors can dance as long as they like to the song before ceding the floor to their competitor. This is very unlike most other competitions in the lindy hop scene. The ASDC gives each couple one minute from the beginning of a recorded song to do their thing, followed (or preceded) by an ‘all-skate’ where they share the floor with other dancers. The more organic ‘jam format’ gives dancers a phrase (or two) of music each, and each couple or dancer must enter and leave the floor at the beginning/end of that phrase. Failing to do so is read as a failure in basic musicality. The Crossover format assumes that a dancer will dance for as long as they need to bring their best shit. Failing to cede the floor is perceived as a failure to judge their audience, the tone of the competition, and a display of egotism. This is where my understanding of the format ends – I don’t know how dancers know when they should bow out, or when everyone knows too much is too much. This format was also used by the Harlem 2011 competition, and it’s interesting to watch all the clips and see how competitors, audiences, judges and MC negotiate an understanding of these rules. Collaborative meaning making or what?!

- Audiences cheer and yell out and otherwise engage with competitors, indicating their approval, admiration, disappointment, awe and so on. This participation is often very important for a dancer making a joke, referencing an historic or iconic move or dancer, or engaging in a little derision, mockery or impersonation. Dancers are focussed on their opponents, but they rely on the audience audibly signaling their engagement with the performance. This all means that the best audiences for these sorts of competitions are also dancers.

There’s so much more to say about this. I’d like to go through and carefully analyse what’s going on in the Crossover clip, and to compare it with various lindy hop and solo clips. There are interesting things to say about the placement of DJs in the competitive space. Or how competitors in a pro or invited jack and jill comp sit in a line at the back of the competition space (they are often actually formally judging each other). This demands comparison with the way lindy hop couples line up in order along the back of the competition space waiting to enter the jam, and are far more actively engaged with the dancers currently on display. And of course, I want to talk about the way the competition space is delineated by these lines of competitors, by the audience, by lighting, by the dance floor itself.

All of these things relate to how the physical competition space is regulated and negotiated by the community, and also by official forces. The ultimate authority is the individual or organisation running the competition. Yet one of the greatest delights in watching street dance (or vernacular dance) competitions is waiting for the moments where rules and authority are deliberately contravened, or at least stretched. When judges request a rematch. When competitors physically touch each other (forbidden!) When competitors touch the audience (doubly forbidden!)

I’d also like to talk about how conversation is managed, both formally and informally. There’s lots of lovely stuff written about all-male and all-female conversation and how formal turn taking dominates all-male talk and interrupting and collaborative meaning making (eg women saying ‘oh no!’ and nodding or saying ‘yes’ regularly interrupt but do not disrupt the speaker) characterises informal all-women talk. I think of dance as discourse, and occasionally use this idea of dance as conversation to explore dance as discourse. It’s not a unique idea – dance teachers use this idea all the time. But while I might have begun thinking of dance partnership in particular as conversation with formal turn taking, I’m now a lot more interested in a model of high level partner dancing as more like collaborative, overlapping conversation. And of course, I extend this idea to include jazz music, with its sections of structured unison, its layers of individual, interrupting parts, and its moments of solo improvisation. I probably like New Orleans stuff because it favours layers of improvisation instead of carefully choreographed unison and demarcated solos.

But enough! I must swim!

![[Portrait of Billie Holiday, Downbeat, New York, N.Y., ca. Feb. 1947] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4085/4843765564_00902754bd_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Henry Allen, Onyx, New York, N.Y., ca. May 1946] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4106/4843118971_3cd0b3c99c_s.jpg)

![[View of the Apollo Theatre marquee, New York, N.Y., between 1946 and 1948] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4105/4843733870_60fd250c2c_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Louis Armstrong, Carnegie Hall, New York, N.Y., ca. Apr. 1947] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4091/4843734010_f330d5fc6b_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Louis Armstrong, Aquarium, New York, N.Y., ca. July 1946] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4084/4843734212_5008ac7ed2_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Louis Armstrong, Carnegie Hall, New York, N.Y., ca. Feb. 1947] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4092/4843734486_f870e539be_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Jack Teagarden, Dick Carey, Louis Armstrong, Bobby Hackett, Peanuts Hucko, Bob Haggart, and Sid Catlett, Town Hall, New York, N.Y., ca. July 1947] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4090/4843734594_42658e040a_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Louis Armstrong, Aquarium, New York, N.Y., ca. July 1946] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4105/4843120181_da34af6c7d_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Ralph Burns, Edwin A. Finckel, George Handy, Neal Hefti, Johnny Richards, and Eddie Sauter, Museum of Modern Art, New York, N.Y., ca. Mar. 1947] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4109/4843120275_3cc87fae99_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Serge Chaloff, Georgie Auld, Red Rodney, and Tiny Kahn, New York, N.Y., ca. Aug. 1947] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4111/4843120413_b4aa6dee62_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Mildred Bailey, Carnegie Hall(?), New York, N.Y., ca. Apr. 1947] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4088/4843120523_209811298d_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Charlie Barnet, WOR broadcast, Aquarium, New York, N.Y., ca. Aug. 1946] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4103/4843735206_53b520518f_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Count Basie, Aquarium, New York, N.Y., between 1946 and 1948] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4149/4843735328_cd47b1e0af_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Count Basie, Ray Bauduc, Herschel Evans, and Bob Haggart, Howard Theater, Washington, D.C., ca. 1941] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4125/4843735472_04c440bcba_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Ray Bauduc, Herschel Evans, Bob Haggart, Eddie Miller, Lester Young, and Matty Matlock, Howard Theater, Washington, D.C., ca. 1941] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4127/4843735608_1e210cb91d_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Sidney Bechet, Freddie Moore, and Lloyd Phillips, Jimmy Ryan's (Club), New York, N.Y., ca. June 1947] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4103/4843735718_6753e3cff0_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Leonard Bernstein in his apartment, New York, N.Y., between 1946 and 1948] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4148/4843735826_c56c908e38_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Leonard Bernstein, Benny Goodman, and Max Hollander, Carnegie Hall, New York, N.Y., between 1946 and 1948] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4132/4843121315_e82ecc5064_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Eddie Bert, 1947 or 1948] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4106/4843736096_2449418f1e_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Lawrence Brown, Aquarium, New York, N.Y., ca. Nov. 1946] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4127/4843121695_6166d65a4f_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of George Brunis and Tony Parenti, Jimmy Ryan's (Club), New York, N.Y., ca. Aug. 1946] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4105/4843736496_de640e6e21_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Billy Butterfield, Columbia studio(?), New York, N.Y., ca. Mar. 1947] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4084/4843736638_433e95d910_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Cab Calloway, New York, N.Y.(?), ca. Jan. 1947] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4091/4843122063_bd787cfd39_s.jpg)

![[Portrait of Harry Carney and Russell Procope, Aquarium, New York, N.Y., ca. Nov. 1946] (LOC)](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4107/4843736970_30ca4177b6_s.jpg)