I’ve seen this image being circulated a bit on facebook this week.

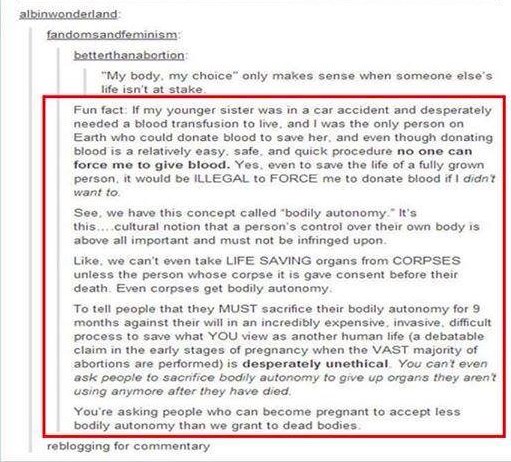

[Text reads:]

“My body, my choice” only makes sense when someone else’s life isn’t at stake.”

reply:

Fun fact: If my younger sister was in a car accident and desperately needed a blood transfusion to live, and I was the only person on Earth who could donate blood to save her, and even though donating blood is a relatively easy, safe, and quick procedure, no one can force me to give blood. Yes, even to save the life of a fully grown person, it would be ILLEGAL to FORCE me to donate blood if I didn’t want to.

See, we have this concept called ‘bodily autonomy’. It’s this…cultural notion that a person’s control over their own body is above all important and must not be infringed upon.

Like, we can’t even take LIFE SAVING organs from CORPSES unless the person whose corpse it is gave consent before their death. Even corpses get bodily autonomy.

To tell people that they MUST sacrifice their bodily autonomy for months against their will in an incredibly expensive, invasive, difficult process to save what YOU view as another human life (a debatable claim in the early stages of pregnancy when the VAST majority of abortions are performed) is desperately unethical. You can’t even ask people to sacrifice bodily autonomy to give up organs they aren’t using anymore after they have died.

You’re asking people who can become pregnant to accept less autonomy than we grant to dead bodies.

[/]

I have a few problems with this chunk of text.

The first is that it’s based on a false premise: that ‘we’ all have the same bodily rights, and that these rights are applied to us equally. I’m going to assume that the author was writing in, and about the US. And I want to state, very clearly, that even beyond the world of childbirth and reproductive medicine, we do not all have the same bodily autonomy. Women of colour, people of colour, first nations people, women, children, gay men living with AIDS… basically everyone other than straight, white, wealthy men have their right to bodily autonomy curtailed by the law, by the state, by medical institutions.

The history of the US is based upon slavery, the clear legal fact that some people can be owned by other people. First nations people were not (are not?) considered people at all by invading colonisers. People of colour are more likely to be incarcerated. Women’s accounts of their own physical pain or illness are less likely to be taken seriously by doctors than men’s accounts. Children are legally not capable of bodily autonomy.

..and so on.

We cannot talk about abortion without also talking about social context. Women and girls are not considered capable human adults or citizens in the way that white men are. We are not considered capable of making sensible, logical decisions. About anything. Let alone our bodies.

I feel that a debate about abortion is a misdirect.

Access to free, safe contraception and good sex education are the demonstrably better way to reduce abortion rates. And incidentally increase women and girls’ autonomy and social power.

By focussing on abortion, rather than sexual health, the discussion is framed as one of individualism, rather than collective responsibility. If we focus on women’s choices, we can avoid a discussion about the state’s role in health care. If we suggest that women’s bodies and their choices are the problem, the we don’t have to talk about the importance of the welfare state in caring for children. Because there, of course, we are reminded that women were once girls, and girls’ education and bodily autonomy is the real issue here.

The abortion debate is about legislating women’s bodies, but more importantly, it’s also about restricting women and girls’ knowledge of their own bodies. I want to expand from this to tie contraceptive rights to access to education generally in a more direct way.

We know that access to education – going to school – generally reduces birth rates (ie girls are less likely to have babies, and fewer babies). For a range of reasons including (but expanding far beyond) knowledge and tools for preventing pregnancy.

The thing I’m often struck by in this sort of debate is the implication that the only reason women and girls have lots of babies is that they don’t know how to stop themselves getting pregnant. Or that they don’t know penetrative vaginal sex with a man leads to pregnancy.

But we know that choosing when and how to have a baby is about more than knowing how to stop sperms get into eggs. It’s also about having a range of choices and options for employment, education, community participation, etc etc etc.

Good education isn’t just about ‘not getting pregnant’ it’s about being able to choose when and how we do have children.

An educated girl is a mighty person. She knows how to access all sorts of resources. She’s not confined to a domestic space and domestic isolation. She’s a _citizen_. This is far more frightening for fundamentalist christians and other patriarchal institutions.

As an addendum, I’ll also note that good sex ed isn’t just about how not to get pregnant or STDs. As that story about the young Swedish men who intervened in a rape in America shows, good sex ed also teaches men and boys about how to communicate with and empathise with their partners’ needs and desires. I think that this is the other thing that terrifies the patriarchy: that men and boys might begin to think of us as humans.