I think it’s worth copying this discussion from fb to here. Not too long ago I got into a ‘discussion’ on fb about why codes of conduct are important. One of the things that struck me was how aggressively one woman rejected the idea of structural change to reduce attacks on women (ie codes of conduct), and also tried to get me to moderate my tone. A bit of ‘tone policing‘.

I often have people (especially men) say they won’t read what I write, or don’t think what I’m saying is important because I swear too much, or because I’m ‘too aggressive’. In the case of this woman, somehow a discussion about whether codes of conduct are important became a bit of a ‘pity party’ for her. It was interesting, because I see this sort of tactic from women quite often. They’re disagreed with, so they respond by playing the martyr so people will ‘stop being mean’ (read: stop disagreeing with them). This is interesting in this case, because she’d said earlier in that thread that she didn’t think we needed codes of conduct because she feels confident enough to speak up for herself.

The tone policing is important, because the very point of the discussion was to change conditions so that women had more room to speak up for themselves, to accuse an attacker, to prevent harassment of other women, to agitate for social change, to be disagreeable.

I find that whenever I’m particularly confident or fierce in my language (even without swearing! :D ), I’m described as being ‘aggressive’ or ‘bullying’. When I reread what I’ve written, I’m really not being aggressive or bullying. I’m being confident. What I suspect is that the cliche of people seeing a woman who speaks at all in public as ‘aggressive’ applies here. And, more importantly, this idea of an ‘aggressive’ woman is deeply unsettling. For men, and for women who identify with a conventional gender identity.

There’s a lot going on in this exchange, but the bits that caught my interest were:

- this woman used her personal experience to justify resisting a policy which would protect people who had other experiences;

- the combination of ‘I’m strong enough to speak up for myself’ and the ‘stop being mean!’ in her language. It was conflicting logic which unsettled the discussion, and established her as a little ‘unstable’ and conventionally feminine (hence justifying the idea that we should be kind to her);

- I was actually rather moderate in my responses to her – I didn’t swear at her (I rarely do that; I swear near people all the time, but very, very rarely swear at people – that’s not cool), but I very clearly engaged with her points individually. This was the point at which she switched tactics from ‘oh, but I don’t think we need that’ to ‘don’t be mean!’ She positioned herself as being ‘attacked’, rather than being engaged in discussion;

- somehow we ended up a long way from a discussion of actual, physical attacks on women, instead having one woman positioning herself as ‘under attack’ when she was really just being disagreed with.

This is something that women often do. They manage a conversation that isn’t going their way through a combination of performing a defenceless victim role, and quite selfish arguments against working to safeguard other women. To me, this is the most disturbing part of patriarchy. It recruits women in their own disempowerment.

One of the consequences it had for me, was to doubt my own thinking. Was I ‘being mean’? I went through and reread the discussion. No, I wasn’t. I didn’t add any personal attacks (where I attacked her, rather than her argument), I didn’t get nasty with her. I just engaged each of her points, outlining how they were inaccurate. I think this was the issue: she saw a sustained disagreement as an ‘attack’.

I know there comes a point where we should abandon arguments online, or face to face. For all sorts of reasons. And usually I do, because GOD TIRED. But at that point I decided I’d see this through and untangle each of the points she presented.

What I was left thinking, was that when a woman does engage in public disagreements, using consistent, persistent logic or resistance, she’s perceived as ‘aggressive’. This is so in conflict with my training as a Phd and MA candidate, that I can’t quite accept it. I am trained to think through a point to it’s logical conclusion. I’m trained to hang onto an idea, working it over and over, to see where it leads.

I know that women are trained to avoid conflict, to use other methods for disagreeing or disapproving. But I think that it is important to be persistent in discussions sometimes, particularly as a woman. I deliberately chose not to adopt that preferred feminine mode of response where I would have apologised or reframed my points to make her feel comfortable. I wanted to discomfort her logic. Just that one time.

Because I get so tired of being sensible and calm and gentle. I’m tired of hearing the ‘you catch more flies with honey’ line. Being angry is important. And in this instance, where we are talking about sexual assault, physical attacks on women, I think it essential that we get angry. We need to persist. Being angry and loud and disagreeable is powerful. It’s feminist. It should unsettle and disturb. Those men who harass women rely on their not speaking up. They rely on women keeping quiet to avoid drama, violence, or being accused of being ‘aggressive’. So we should practice speaking up.

Anyhoo, moving on. This exchange was an example of how one woman argued that her personal experience was justification for not adopting systemic change.

I’ve also heard this argument against adopting codes of conduct: ‘we deal with these issues on a case by case basis’. This argument is a way of insisting that individualism is more important than collectivism. Or, more clearly, it makes it impossible to see the forrest for the trees. If we respond to each assault as a ‘single case’, we are so busy dealing with ‘cases’, we don’t see patterns. I think that the case by case approach is an explicit tool for resisting change, and enabling sexual assault. Because it responds to sexual assault, rather than preventing it. Assaults will still happen; women will still be attacked. The power of the authority ‘dealing’ with incidences is maintained; women are kept powerless. They’re not given tools to prevent assault. Men aren’t taught that assaulting women is not ok. I discussed this in my previous post, ‘yes all men, and all women. all of us.’.

Societies and cultures and communities are groups of individuals. But we are also people with shared experiences, and there are patterns of behaviour and experience. Collectivism is an important concept if we are to prevent sexual assault, not just respond to it.

Anyways, this brings me to my next point. That post ‘yes all men, and all women. all of us.’ was a post on fb. And one of the comments was quite interesting. A man asked:

What’s an example of a systemic barrier in organisations? I’m not being difficult, it’s just sometimes easier to see things once they’re pointed out that’s all

This was the perfect question. If we aren’t dealing with sexual assault on a case-by-case basis, if there are ‘systemic barriers’ (or broader cultural patterns of disempowerment), how do we identify them? This is a tricky one. And such a good question.

I replied:

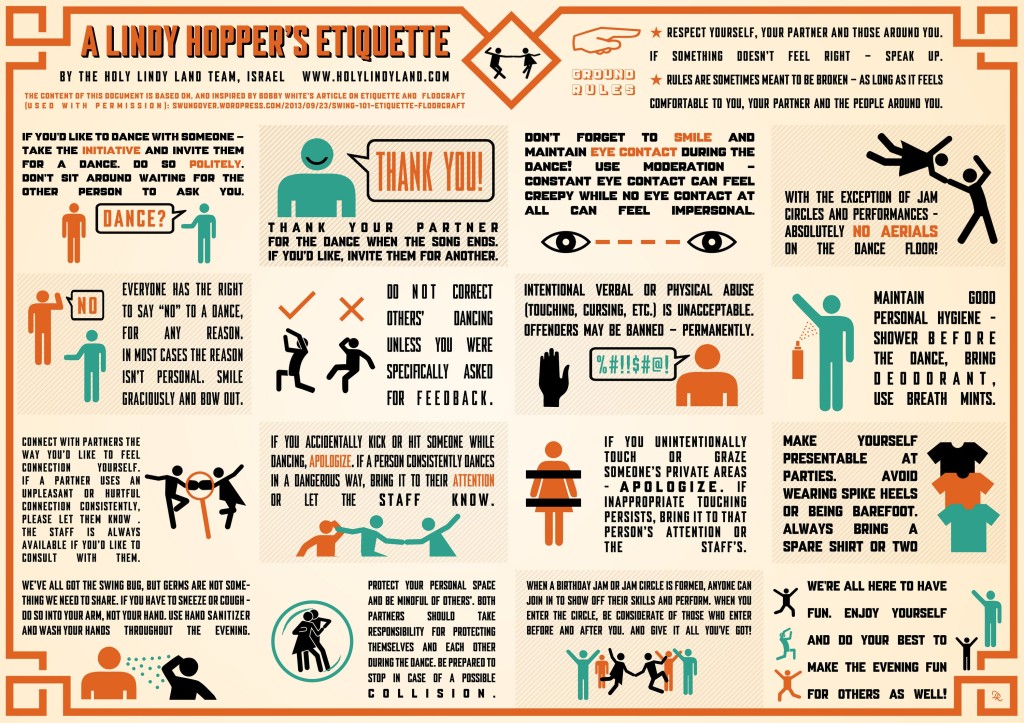

In a lindy hop context, not paying women teachers as much as male teachers, or only offering dances classes at the times babbies need the most care (ie 6.30pm). Both are examples of how an organisation or system makes it harder for women to continue teaching or learning, and favour men or people who don’t have child-caring responsibilities.

Still a systemic barrier, but more about discursive barriers: always referring to follows as ‘she’ or ‘ladies’.

Learning to see barriers is harder if you tend to benefit from barriers that affect others inversely. I keep my radar out, and the things that usually ping that radar are, for example, structural things that are divided by gender, or only affect women. So, for example, ‘wearing high heels in lindy hop’. If only women wear heels, or are encouraged to wear heels, I’m immediately suspicious. Similarly, if beginner dance classes divide students into leads and follows, but use gendered language to do so (eg ‘ladies over here, men over here’).

Context is important, of course. So because we live in the context of patriarchy, I tend to be suspicious of things that are related to gender. But you might also be looking for things like ethnicity: are all the teachers in a school white/anglo? Are all the performers in a troupe white/anglo? Are all the students in a class white/anglo? If that’s the case, then the next step is to ask ‘why?’ If you see broader patterns, then it’s probably structural or systemic barriers at work, preventing or discouraging certain people from entering the group.

The next step is then to start investigating. You can ask people of colour (POC) why they aren’t taking dance classes, but it’s more useful to start by observing things like language, social settings, clothing and other cultural stuff, etc etc.

Luckily, we have a few generations of feminists and other activists and thinkers to give us an idea of what to look for, and how to look for it.

Probably the most important tool for you, as hooman, is critical thinking. If you see something (eg no women on a DJing team), ask ‘why’, rather than just accepting it, or accepting an excuse like ‘there just aren’t any women DJs’. Similarly, if we see it’s only women, or mostly women being sexually harassed in a dance scene, ask ‘why?’ Because there are patterns (ie it’s women, not women and men being harassed in large numbers), then there are probably broader factors at play, beyond individual people – eg systemic, structural, discursive, cultural factors.

Once you’ve observed those systemic barriers, you can set about dismantling them. If you are in a position of relative privilege, then you are in a great place to do this sort of work.

I feel, as someone who benefits from systemic barriers (because I am a white, middle class women living in a big city in a developed country), I feel I have a responsibility to ask questions, and to be curious or suspicious. The nice thing about jazz dance, is that as a vernacular dance (ie a street dance, or ordinary social dance), it really works well as a tool for changing things, or asking questions, or being curious and creative.

I think, then, to summarise, addressing systemic change is about empathy. Thinking beyond your own personal experience. And I think that this is where my real problem with that woman at the beginning of this post lies. I believe in using empathy, imagining what it’s like to be someone else, to address patriarchy. That woman made an explicit call for empathy: ‘don’t be mean’. But I persisted, even though it caused her discomfort. Was this unfeminist? If sisterhood is at the heart of feminism (for me), then should I have stopped ‘being mean’?

It’s a tricky one. When I write on fb or here on this blog, I always remember that there are far, far more people reading along than commenting. So when I continued in that discussion, not heeding her ‘don’t be mean’ response, I risked alienating readers. Particularly female readers.

But I know that demonstrating how different ways of being a woman is important. Just as the best way to get more women leading in lindy hop is to have more women leading in lindy hop, having women speaking up and being disagreeable – and coming out of it unscathed – is a way to model speaking up for yourself when you’re sexually harassed.

The irony, of course, is that many conservative peeps find it difficult to empathise with women who aren’t conventionally feminine, who aren’t quiet and meek victims. Who are confident and vocal and disagreeable.

But as we all know, bitches get shit done.

In that setting, I figure I can be that outlier – the bitch at the far end of the spectrum. And hopefully someone else can fly under the radar, being sneakily subversive, rather than loud and stroppy. Me, I don’t have the patience. I’m femmo stroppo because my friends are being assaulted – attacked, raped, hurt – by men. And there’s no time to waste.