Damon Stone, a high profile black male blues dancer recently made this post on facebook:

Blues dance post following –

Asking for consent before dancing in close embrace. If you are at a blues dance and someone asks you to dance, the expectation is that you are going to do blues, be it freestyle or a specific idiom…if they say yes, that *is* consent for you to dance in close embrace.

Like all other activities and aspects of consent, such consent can be withdrawn at *any* time, but if you do not want to dance in close embrace with someone politely refuse the dance. If you don’t want to dance in close embrace with anyone, then, respectfully, find a different dance.

EDIT: This is assuming two things, 1) that the person is dancing correctly, 2) that not every single blues idiom dance is a close embrace dance, but blues idiom dances use close embrace as their starting position.

I read this post in light of the recent (and most excellent) comments by black women about white blues dancers (which I note in my post ‘Stop Dancing’), and ongoing about how to negotiate consent and avoid sexual assault and harassment in the contemporary blues, balboa, and lindy hop scenes.

My response was as follows.

I think there are a few issues here for me as a dancer and observer:

– One is the history of blues (and we are talking about a dance that includes a very close embrace – just as tango does),

– One is the different current cultural contexts of blues music and dance around the world today,

– And one is the different notions of consent and negotiated physical contact in different cultures today and then.

I think this statement is problematic:

If you are at a blues dance and someone asks you to dance, the expectation is that you are going to do blues, be it freestyle or a specific idiom…if they say yes, that *is* consent for you to dance in close embrace

Why?

Because people take this statement and this concept at face value. As a relatively experienced dancer, I know what it means: if I go to a blues party at Damon’s house, I should expect some pretty close physical contact. I’ll be able to tell a bro or a woman to back off if I’m not ok with what they do, but I should expect a close embrace (vs no physical contact at all, as at a tap jam).

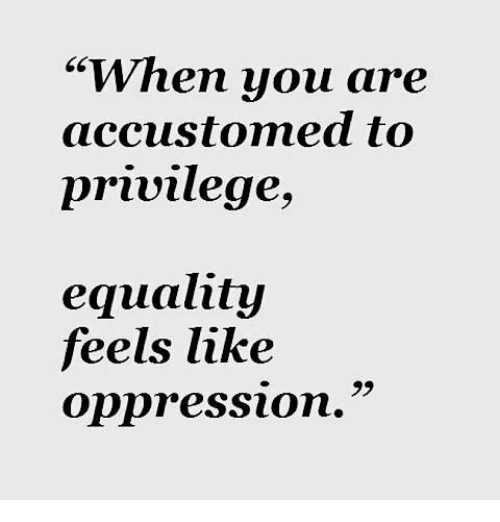

But an awful lot of people take this sort of dance etiquette and map it onto their relationships throughout the dance world. An awful lot of men and women are trained to expect this: that a woman or man must say yes to a dance invite, a close embrace, a partner doing as they like with our body. Because an awful lot of people don’t know how to touch other humans with respect.

In my world (fuck, in Trump’s world), men expect to touch women as they like, women expect that men will try to touch them without permission, and learn to avoid that in a non-confrontational way. Men learn to exploit this and exploit women.

So when we go to a blues dance, some people need to be told, explicitly: you don’t get to do what you like to your partner’s body. You have to ask permission.

I’m rolling my eyes too. For fuck’s sake.

Blues as a historically-rooted dance comes from black communities, where notions of how to touch and when to touch and who to touch were something black kids learnt growing up, engaged with as teens, and then continued to negotiate and renegotiate as adults.

These ideas of ‘appropriate’ touch, how to ask for permission to touch, how to reject touch and so on weren’t monolithic across black communities in the US. I mean, there’s that iconic story that Frankie Manning told about imitating his mother dancing by dancing with a broom and getting into big trouble. The implication here is that dancing that way was something adults (sexually mature people) did. And they certainly didn’t do it across generations (part of his mother’s reaction was no doubt to do with the fact that Frankie was watching his mother, not some random woman, in an intimate embrace).

So we have generational differences then. We also have generational differences now. And young women regularly police the boundaries of when old is ‘too old’ to dance intimately (and sensuously) with (“eee gross! He is too OLD for you!”)

Then of course, we have different regional differences (country v city, city v city, etc), and different class differences (eg the super close intimate dancing has long been associated with ‘low’ culture, and wasn’t appropriate for huge, cross-generational dances in ‘polite’ company).

In all those spaces, people figured out what was appropriate and what wasn’t. A good slap would tell a man if he’d crossed a boundary. From that woman, or her brother or father. And then a series of stern frowns, lectures, and ‘punishments’ from a world of aunties and grandmas and mothers.

But, for many dancers today, blues dancing isn’t situated in that close community network. Their aunty is never going to know what they did at that party and come after them with a broom. There isn’t that inter-generational education about how to touch and be touched on the dance floor.

Blues dancing today also exists in lots of different cultural and social contexts, with all sorts of attendant social mores and modes of behaviour. We are at this moment having very public discussions about the role of race, cultural heritage and who gets to police these values. Who gets to speak in these discussions, who gets listened to, and whose words last are subject to broader socio-political forces.

I’m saying this not to be patronising (I know you all know all this), I’m saying it to signal that I’m aware of these issues. I need to talk context, and I am aware of the bigger issues, and the intensely personal issues at hand.

But I think that one of the voices I’m not hearing in many discussions about blues dance (and how to touch a partner on the dance floor) is black women’s. I think that Cierra’s Obsidian Tea piece about dating is really useful here, for me (as a white woman in another country). It says, ‘Hey, mate, your rules of physical intimacy may not apply here. Pay attention.’ So I’m paying attention.

BUT there is also an ongoing contribution from black women talking about their rights to decide how and when they give consent, and to whom. As a full-on example, a queer black woman at a blues dance not automatically give consent for a man to hold her in a closed embrace. Nor does a straight black woman. They might not need to give and receive verbal consent, but they certainly have a right to set boundaries about their bodies.

So I figure: in this moment, when we are renegotiating blues and lindy hop, we don’t assume anything about how we touch other people’s bodies. I might go to a tango practica expecting to be held and to hold in a very close embrace. But each dance that I have in that session will involve some degree of negotiation. I might invite a close embrace, but I might also reject it. I might end a dance early. I have a right to do all these things with no notice, both on and off the dance floor. How I do this depends on the traditions of that scene, and my own social skills (or lack thereof).

In my culture (white woman in urban Australia), women are strongly discouraged from publicly embarrassing men. To protect their own bodies, but more to protect the reputations and status of that man. So we are trained not to slap a handsy man on the dance floor (though goddess knows I’d like to). We’re trained not to say “STOP THAT” to that handsy man on the dance floor. We’re trained not to move away from that handsy man on the dance floor.

And I don’t know what a black woman my age at a party in Chicago would do in those situations either. I’d probably watch and learn, and ask my female friends questions, and figure it out. But I’m in Australia, and I’m white. So I’m figuring it out long distance. And this is why I really really want to see black women talking about how they do this stuff.

We might sensibly assume that if we go to a blues dance or event that is advertised (or described) as a party in the sense of the historic blues idiom, that we might be doing some close embracing on the dance floor.

(which I think is your original point, Damon?)

BUT I think that we should never assume that we can embrace someone or touch someone without asking for and receiving consent to do so. And to continue to check in and to see that our partner is ok with this. And being prepared to end the dance ourselves if our partner isn’t into it, or if our partner wants to end this.