(John Lee Hooker, 1951, photo by Clemens Kalischer, found on Chasing Light)

[I’m DJing at the Jook Joint on Thursday. It won’t be like this. Bedlam Bar, 2 Glebe Point Rd, social dancing starts 8.30.]

(John Lee Hooker, 1951, photo by Clemens Kalischer, found on Chasing Light)

[I’m DJing at the Jook Joint on Thursday. It won’t be like this. Bedlam Bar, 2 Glebe Point Rd, social dancing starts 8.30.]

In a post on FB, Chris asks

Charm’s Question of the 1st of June:

Blues dance draws from a rich cultural well, a constant evolution of the dance and rapid socio-economic changes.What elements of vintage Blues dance culture (sordid and scandalous though they may be) need to be incorporated into the modern dance form while coupled with more professional dance training?

Disappointingly, I think I’m more interested in children’s rhyming songs, skipping ropes and household chores.

I read this as I was writing that last post The Rules of Connection: I think about pedagogy, lindy hop and ideology, so I ended up replying to Chris with this fairly off-topic and annoyingly preachy comment:

I have some troubles with the way ‘professional dance training’ is often defined or practiced.

I don’t accept the premise of this question: that ‘professional dance training’ (as it is defined and practiced in most of the modern swing/blues/whatevs world) is an integral part of blues dancing or learning to dance. I’d probably ask ‘how might dance pedagogy and learning dance (the two are not necessarily codependent) today draw on the history of blues dance (and music)?’ or, in SamTalk: “What can I use from the history of blues dance to become a moar orsm dancer?”I’m actually very interested in dance as a point on continuum of everyday rhythmic movement, rooted in history and culture (which I think dance is often separated from by ‘professional dance training’).

So I like to chase down ideas about moving your body in rhythmic ways which aren’t necessarily dancing. It’s about training your brain and training your body.

eg I think this video is a good tool for thinking about and physically learning about rhythm, swing, delay, etc: http://youtu.be/2vy0dMXhlWI

This one for thinking about rhythm, timing and performance: http://vimeo.com/20853149

Or this one for ideas about rhythm, partnership and athleticism: http://youtu.be/bDOBcBKRENw

It’s an interesting question, because it’s actually asking (I think):

How can we use history (of blues dance and music) in modern teaching practice?

Which is almost exactly the question I ended up asking in that last post (The Rules of Connection: I think about pedagogy, lindy hop and ideology). How do we use history in modern dance teaching? This is something I’ve written heaps about. Heaps and heaps. I’ve gotten angry about the way some dancers and teachers insist on male/female partnerships because ‘that’s how it was in the old days’ (yes, there were male/female partnerships in the old days, but ALSO LOTS OF SAME SEX PARTNERSHIPS). I’ve gotten angry about dancers and teachers insisting that we should wear vintage clothing (shoes, dresses, suits, whatEver) because ‘that’s how it was in the olden days’ and ‘it makes you dance more better’. My standard response, at a higher level is ‘I can dig historical stuff, but I don’t want to recreate all of the history. I like having access to a good doctor, a dentist, clean drinking water, the right to own property and fucking awesome running shoes.

So I reckon we can assume that ‘just recreating’ the past isn’t really what we want to do. Well, it’s not what I want to do. That last post began to explore how I think about using history in teaching actual dance movements: I am unsure and still figuring things out.

As a dancer myself, I use historic photos, stories, footage and music to help me think about how to move my body, and what my body looks like.

In all these examples, historical footage, photos and stories are really important to how I think about learning to dance, how I think about choreography, how I think about music and how I think about getting DOWN on the dance floor. I can borrow from history (textual poaching, yo!), but I don’t have to seek to recreate it exactly.

So in that response to Chris’s question on FB, I wanted to side-step a discussion of formal teaching processes by referring to LeeEllen Friedland’s discussion of a continuum of cultural practice.

I can’t find a copy of her article online, so I had to look it up in my thesis notes. This is what I wrote about learning to dance in vernacular dance cultures:

In vernacular dance culture, acquiring dance knowledge and learning to dance, developing “new steps” and becoming conversant with dance floor politics is not a formal process conducted in dance studios, but a matter of acquiring life skills particular to a community. Sheenagh Pietrobruno argues that vernacular dance is created in a “lived context”, and is:

not formally learned but…passed on from generation to generation. Most people who grow up with the dance acquire it in childhood, its movements often taught indirectly through the corporeal language of the body, so that those raised with the dance may not have a sense that they have learned it. Dancing usually is done to music: there is no separation between the rhythm of the music and the steps of the dance (1).

Pietrobruno’s discussion of salsa is equally relevant to a discussion of African American vernacular dance, particularly as salsa – as a Cuban-identified dance – has strong cultural links with African American dance, as do many other vernacular dances of the Americas.

Pietrobruno introduces her discussion of teaching and learning salsa in Montreal by emphasising the position of vernacular dance within the everyday, and learning to dance as an everyday activity, rather than a ‘special’ event bracketed off into designated dance spaces. In this way vernacular dance across cultures is bound to live music and other vernacular cultural practice, it is communicated across generations and it is an extension of ‘wider cultural expression’:

The salsa that develops in a lived context involves more than a series of steps and turns: dancers execute movements with their entire bodies. The subtle, but essential elements of the dance, such as how dancers hold their bodies, move their heads, position their hands and isolate various body parts are rooted in motor control and movements that are extensions of wider cultural expression…A child may be formally taught specific footwork and turn patterns of salsa, but picks up body isolations by experiencing the family dance culture, similar to acquiring everyday gestures. Although these subtle separations of parts of the body may seem effortless to the outside viewer, their performance involves a great deal of skill and dexterity. Individuals of Latin descent, who are dispersed throughout the Americas, often learn the dance as an extension of their heritage (1).

Learning to dance in a vernacular dance culture is a process akin to learning to speak. Children acquire ‘vocabulary’ – dance moves – through imitating adults, through play, and everyday activities. The process of gaining discursive proficiency requires constant and everyday experiments with communication. Families, peers, and other groups and individuals in day to day life contribute to a child’s acquisition of dance skills.

Friedland explores the acquisition of dance skills in vernacular dance culture in greater depth in her article “Social Commentary in African-American Movement Performance”, where she discusses the role of dance in urban black children’s lives in Philadelphia. Though researched in the 1970s and 80s, Friedland’s work is as applicable to communities of dancers in the 1930s in Harlem as it is to black dance culture in Los Angeles today. Friedland makes several key points in her work. Firstly, and most importantly, she states that dance in African American communities is not segregated from everyday activity. Dance movement itself is part of a “complex of interrelated communicative and expressive systems that constitute a whole world of artistic performance” (138). These systems include body movement, sound (including music), visual forms (including drawing and wall art, costume and hair style), language (including slang, rap and poetry) and ‘attitude’ (including ethics, creativity, aesthetics and social behaviour). Participating in all these systems is central to black children’s lives, Friedland argues, and is, it is implied, equally as important to black adults.

This continuum of creative cultural practice, and the continuity of themes and interpretive and creative practices across media and practices is reflected in the cultural practices of contemporary swing dance communities. Study of contemporary swing dance culture suggests that the older a community, the more varied its inter-community networks, the more diverse its borrowing from other cultures, the more sophisticated its own cultural practices and shared systems of meaning. This point has directed my attention towards DJing, audio-visual media and dance pedagogy in contemporary swing dance culture, as an exploration of the ideological relationships between cultural practices and media use in a particular community. As Friedland suggests, systems of meaning in dance are not discrete. They are constructed intertextually, echoing broader ideological and discursive structures within that community.

It is therefore unsurprising to find vernacular dance, as part of a system of cultural practices connected by ideology and social networks, is not only ‘performed’ on stages, but also in competitions or even on the dance floors of balls or social dances. Friedland makes her second, and perhaps most important point, that dance and dance movement are part of everyday life and movement in vernacular dance, and that dance carries with it social and cultural meanings and relationships. Both Friedland and Pietrobruno therefore argue that ways of dancing are extensions of cultural ways of being. Friedland in particular extends Pietrobruno’s point that dance “movements …are extensions of wider cultural expression” (Pietrobruno 1). The discussion of dance movement as a subclass or an extension of the notion of ‘dancing’ in Friedland’s work encourages us to expand our conception of ‘dance’. Movement – ‘body language’ – is not simply a visual illustration of spoken language. Dance and rhythmic movement are part of a wider system of cultural production and communication as viable discourse and communication in themselves.

Dance and rhythmic movement are therefore as important in the African American culture Friedland describes as spoken and written language is in mainstream Australian culture. She discusses a range of categories of dance movement, from ‘being rhythmic’, to ‘dancing’ and ‘movement play’. These categories are seen as testing grounds for children’s developing ‘dance’ or ‘movement’ repertoire, and concurrently, their social and cultural repertoires. Friedland discusses black children’s ‘learning to dance’ as a process of enculturation, where children are not only taught formal steps from older children and adults, but also encouraged to move in particular ways, and to read the movements of others on particular terms. This approach encourages us to think of dance and movement not as innate or essential abilities, but as learned cultural expressions.

The mythic association of African Americans with ‘natural rhythm’ and expressions like ‘white men can’t jump’ (as discussed in Jade Boyd’s article “Dance, Culture, and Popular Film: Considering Representations in Save the Last Dance”) are reframed by Friedland’s work as racialised, essentialist statements about ethnic identity and culture. Dance discourse and ways of moving are learnt rather than innate. They are culturally determined. With this in mind, we can draw on a range of dance studies literature to make observations about how dance movement and dance culture cross-culturally function as discourse.

So, with all that in mind, I figure that to really understand blues and lindy hop and all those historical dances, you really have to think about everyday cultural context. As a white, middle class woman living in Sydney in the 21st century, I’m never going to be able to truly recreate those original cultural conditions. And it’s a bit silly to try, as I don’t want to, not even if it meant becoming a brilliant dancer. But it does mean that I’m very interested in childrens’ games and videos like Stop Clap Go:

I’m also interested in adaptations of children’s games like doubledutch in a postcolonial/multicultural/disapora context:

And I think we can learn useful things about rhythm from everyday movements and activities:

(linky)

References

Friedland, LeeEllen. “Social Commentary in African-American Movement Performance.” Human Action Signs in Cultural Context: The Visible and the Invisible in Movement and Dance. Ed. Brenda Farnell. London: Scarecrow Press, 1995. 136 – 57.

Pietrobruno, Sheenagh. “Embodying Canadian Multiculturalism: The Case of Salsa Dancing in Montreal.” Revista mexicana de estudios canadienses, Vol. verano, No. 3, Jan. 2002, pp. 23-56.

John Lomax

Alan Lomax

Library of Congress’ Archive of Folk Culture

The American folk music revival (NB the blues revival, and the American musicians touring Europe)

the Jelly Roll Morton Library of Congress recordings

The Smithsonian folkways label

I have some things I want to say about the intersection of dance and audio-visual media, but I don’t have time to make a whole, proper argument. Fuck, I took 100 000 words to talk about these issues in my phd dissertation, so I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to write about this succinctly.

But let me note the ideas that happened to me today. Firstly, someone else made a very interesting observation.

Jerry linked up an interesting video on Facebook.

MOTION #04 – Ledru Rollin by motionparis

And he wrote:

Via BrotherSwing. This is a pretty slick video featuring Melanie Ohl. However this does highlight an interesting conundrum with these kinds of videos in that the editing is so quick that it’s hard to get a sense of how well the dancer is actually moving. I’ve seen other videos of Melanie, and she is pretty good, but the camera doesn’t stay on her for more than a few beats at a time. On one hand it does keep the casual viewer engaged, but it makes it difficult for someone trying to enjoy just the dance itself.

I’m starting to pay attention to more of this stuff as I’m making my own foray into the netherworld videography with my new camera. Plus a lot of Lindy Hoppers are now getting the opportunity to be filmed all fancy like, I’m actually working on a short video which I may post very soon.

Also, this seems to be a part of a series of videos focusing on different dancers doing different dances, so if you enjoy this, check out the user’s main page for more.

I’ve been paying (some) attention to the way dancers’ve been getting into vlogging lately (eg Mike Pedroza is using youtube and Jerry is making interviews and other fun things (again via youtube, but with his blog and FB page as the key delivery tools)) and I’m always interested in dance-musician video projects.

This is partly because I’m a dance nerd, but much more because I spent a really long time learning and reading and thinking and writing and teaching about media and audiences at uni. I’m really, really, really interested in audiences and modes of participant-consumption (no, I am not ok with the term ‘produceage’). That’s really how my phd began: how do dancers use digital media in everyday dance practice? I wrote about AV media, DJing, email lists and discussion boards, and I can’t seem to stop thinking about this stuff. I guess I just can’t get away from the idea that dancers are all about the body – the face to face interaction – and yet swing dancers are very into digital media. There are all sorts of interesting class, culture and ethnicity issues at work here.

In my own work I carefully avoided talk about Cartesian splits, because I don’t think it’s a terribly useful model. Dancers don’t divide their brains and their bodies, and to insist that dancing is always and forever a thing of the senses and the body, is to devalue the work of choreography and the social labour of production and consumption surrounding the dance floor… or those three minutes on the dance floor. Just as I feel that it does musicians a disservice to dismiss the best jazz as ‘creative magic’, I think it is a mistake to talk about dance only as creative magic happening in the body.

I think that the dancers who achieve the greatest things do spend a lot of time thinking about dance, and how dance works, but they spend even more time on the dance floor, moving, and finally (and always?) they are thinking with their bodies. So I don’t like that idea of a mind/body dichotomy. And we do need to consider the idea that thinking about dance can happen via digital media as well.

I know I’m not the only one who can’t watch dance videos before bed because they keep me awake. I’d always joked about ‘Pavlov’s lindy hopper‘, but then I came across an article by Beatriz Calvo-Merino, Julie Gre`zes, Daniel E. Glaser, Richard E. Passingham, and Patrick Haggard called ‘Seeing or Doing? Influence of Visual and Motor Familiarity in Action Observation’. Basically, if you wire up a dancer’s brain and then observe them watching a particular dance choreography, the same bits of their brain fire as they would when that dancer was themselves dancing that choreography. CRAZY. So – and I extrapolate wildly and without substantiation here – when I’m watching solo charleston videos before bed, my brain starts firing, and it’s as though I’m dancing that charleston. And then we all know how long it takes to calm down after a bit of crazy charleston. I’m also beginning to suspect that a DJ (who is also a dancer) experiences the same brain-work while they’re DJing and watching the floor. So a DJ who watches the floor should – boy, this is getting precarious – should be a better DJ for this doppelgängering effect. Yes, I know doppelgänger probably isn’t the right word or term to describe this. Mirroring – the term Calvo-Merino et al use – is far more useful.

So, yes, let’s talk about this in terms of ‘thinking with the body’. That idea is useful when we think about choreography – and probably even teaching dance – because it gives the observer a way to feel what is going on in the body of the dancer who is being observed.

Yes, yes, but what has this to do with Jerry’s original post?

This is what I wrote in response to Jerry’s facebook post above:

Oh Jerry, I think I love you. This is so totally up my (media studies) alley!

There’s quite a bit of literature in cinema studies about filming dance. I guess the tension lies in filming dance-as-spectacle in itself (where you basically just set up the camera to film dancers’ whole bodies from a fixed position) _or_ filming dance-as-narrative, where you cut, pan, edit, etc to tell a more complex story about dance and through dance.

I saw a very interesting conference paper by Tommy DeFrantz a few years ago, where he talked about Hype Williams and a “black visual intonation” in music video (Believe the Hype: Hype Williams and Afrofuturist Filmmaking’, ‘Refractory’, Thomas F. DeFrantz, Published Aug 27th 2003). This was basically looking at how we might make music video (featuring black music and dance) in a way that reflects the rhythms and intonations of black music and dance itself. In the simplest terms, that might mean cutting and editing film in a particular rhythm. This immediately makes me wonder what a film cut in a ‘step step triple-step’ rhythm might look like.

Another fascinating example of this sort of thing is the Two Cousins video:

On one level the choreography has been put together as a response to the song. The first ‘scene’ gives us Ryan dancing ‘in time’ to the song ‘Two Cousins’. The film then cuts immediately to a slow-mo pulled-back shot of Ryan dancing, with a busier, more exciting part of the song overlaid. There’s an interesting tension between the more exciting music, the exciting dance steps and the effect of slow motion itself.

I think two of the reasons so many people were irritated by the Slow Club video was that it cut and edited the choreography ‘out of sync’, and it also messed with the speed of the choreography – slowing things down and speeding them up. So our dancer’s eye was continually frustrated by an inability to follow the patterns of the choreography ‘in real time’. Lindy hoppers are pattern matchers, and it’s very frustrating to not get to see the entire pattern of the choreography laid out in real time, so we can comprehend the ‘story’ of the choreography itself – the repeating patterns and rhythms. Refusing to let us see the pattern builds tension (and frustration); we never get the release of closure or pattern-repeating.

In contrast, lindy hoppers tend to really love films like the original Al and Leon videos:

(Charleston — Original Al & Leon Style!!)In these videos there are no cuts, just a few very slow pans. With no cuts, we don’t get that feeling of anxiety about ‘missing’ something that’s been ‘cut out’ of the film: we see the whole thing, in real time. We get to see the patterns and rhythms.

I’m totally fascinated by all this. I’ve written an article about how dancers’ use of AV media changed the way the original films worked as texts. We cut out the ‘dancing bits’ and watch them in isolation from the broader film narrative (which films like Hellzapoppin actually were designed for – censors cutting out the bits that broke race laws). But then we also do things like watch and rewatch, and then watch and rewatch _parts_ of that original scene, out of order. Dancers: we’re all about imposing our own narrative flow. Just like all audiences, really.

Now, to tie all this together. I think, when I wrote about this frustration that dancers feel watching the Two Cousins video, I was referring to a sort of tension (yes, I do overuse that word, but it’s a good one to describe this feeling) that you might feel if you watched this video as a dancer. The Pavlov’s lindy hopper effect kicks in, but then it’s not taken to completion; we don’t get that good old adrenaline contact high from watching this video. Mo frustration!

But this is of course all just speculation on my part. And even I’m highly skeptical. It seems far more likely that the negative comments about the Two Cousins video stemmed mostly from an intellectual and creative frustration with the cutting and ‘obscuring’ of these two gifted dancers. Finally – a high quality video of two of the most difficult-to-catch-on-film, most talented male dancers of our era – and we can’t even SEE THEM! And I’m sure we don’t even need to go into the aesthetic and creative frustrations we feel watching the Two Cousins clip.

Here is where I might insert a bit of talk about the perils of narrative cinema, Laura Mulvey, the male gaze and avant garde cinema. I could go on about how we should be deeply suspicious of submerging ourselves into narrative cinema, and how it is the opiate for our active, interrogative minds. But I can’t support that argument, because I am – unashamedly – a fan of the good story well told. And as someone getting interested in choreography, I’m extra interested in how story structure can work with music and dance to convince audiences they like what they see. I could quite happily go on and on about repetitive structures and just how useful they are for telling stories in dance, but that is way too far OFF THE TRACK even for me. So it’s back to dancers bitching.

So, really, there were lots of reasons for dancers to find the Two Cousins video frustrating. As audiences with shared values (which I guess is how non-corporeal audiences are determined – individuals become audience through shared viewing and shared viewing practices and values), it’s not surprising so many dancers were narked.

But then, it’s also possible to write about the Two Cousins video with some degree of joy as a dancer. I wrote about some of my good feelings about the video in my Two Cousins post.

But even I can’t maintain that blissed out lindy love feeling. I tried to discuss some of the issues of race and discursive and mediated power at work in this and other video performances in ‘Historical Recreation’: Fat Suits, Blackface and Dance. And I went over the details in Another look at appropriation in dance.

That last post about cultural appropriation draws on Tommy Defrantz‘ work, implicitly if not explicitly. Tommy’s work has had a profound effect on my thinking about gender, class, race, dance and power. He is one of the few academic scholars whose work on black dance history can be trusted absolutely. And he’s a dancer himself.

This whole post is leading me to the point where I link you up with this lovely video, Thomas F. DeFrantz: Buck, Wing and Jig:

Which you should then follow up with Thomas F. DeFrantz: Dance and African American Culture:

I especially like the part where he says:

Social dances are hugely important to help us understand how people live their lives. Because in the social dances we see the transformation of physical gesture that people do every day into creative practice, but we also see the fantasy life of social gesture that people don’t get to do in their everyday. …we might see social dances that let people… release all that energy in really unexpected ways.

So Defrantz at once describes social dance as a place where everyday movement is transformed into dance (this is something that gets talked about a lot in other discussions of vernacular dance – especially in LeeEllen Friedland’s work), but also as a place where fantasy lives can be lived out. So we put our ordinary everday into our social dance, but we can also make social dance a place where we live out our fantasies.

This makes lots of sense when you think about gender and dance, and I’ve written before about how social dance might give young women in particular a place to play with gender: femininity, sexuality, desire, and public displays and enactions thereof. But I have always really liked Paris is Burning as an example of shared, public, social, collaborative, creative – fantasy – play in dance. In that film, a ballroom becomes the place where any fantasy about sex, gender, power, beauty, desire, grace, creativity and artistry can be played out.

In an extension of that final point, then, when dancers get to see films like the ‘My Baby Can’t Dance’ video (which I describe in New Chic in Jass), you can see how the camera’s longer, lingering ‘gaze’ upon those dancing bodies (those talented, well-lit, well-dressed, well-known dancing bodies) provides a sort of visual and physical pleasure. I’m not talking sex, here. I’m talking about that Pavlov’s lindy hopper effect. We get the pleasure of seeing someone talented doing a choreography we really like, and we also get the physical/mental pleasure of our observing brain firing and delivering up a good dose of adrenaline.

Now, I’m treading dangerously (frighteningly) close to phenomenology here, and I have to say: do NOT want. I also think that the arguments or ideas I’ve set out here are HIGHLY spurious. You should be very, VERY skeptical of the things I am saying.

But at the same time, aren’t these very tempting, very delicious ideas? Isn’t the thought of getting a ‘contact high’ from watching a dance video a little like an unwrapped block of best Swiss chocolate? Don’t you just want to get all up in its grill?

YES.

So you might have noticed a lack of WHM posts lately. Here is my litany of excuses:

– Hayfever has put me down for the last few days. Big time.

– We discovered a leak into the concrete slab of our flat last week, and have spent a week moving our ONE HUNDRED BOXES OF BOOKS and associated bookcases UPSTAIRS so we can then rip up the carpet in smaller sections to expose the slab. It is now ‘drying’. Sydney has had a spectacularly damp and mild summer, so this ‘drying’ is not happening. We will not discuss leaks, mould and allergy connections.

– I have some other projects on the go which have sucked up my spare brain time. I have, however, quite sore shoulders from so much computer work, so that’s a good thing. I guess. Writing: I did it. Websites: they are maintained!

– The theme I set myself just didn’t inspire me the way the month of women dancers did last year. It seems I am a dancer first and a music nerd second.

– I have a limited block of time set aside for dancing during my day/week, and that block has been filling up with teaching, admin for the classes, various DJing gigs, getting rid of some dance commitments (why is that harder than actually doing the jobs in the first place?), a workshop thing I’m running in May (which will be SQUEE), thinking about promotions and advertising in a long term way (rather than just responding to things), trying to sort out new sound gear for one venue (gee, that task has totally not been done), and then I take on ANOTHER DJing project, which will be super fun, but is perhaps overly ambitious for someone who is supposed to be giving up ocd impulses.

I told you it was a litany.

I had some ideas for posts:

– the role of all-women bands in the first fifty years of the 20th Century, and the contribution they made to jazz (big);

– women in the early days of the recording industry (in which vocal blues and blues queens played a big part, and in which race records are really important, because they marketed those blues queens to black audiences so effectively the white labels started trying to screw them over and steal their ideas and artists), most especially the women working for record labels;

– other stuff.

A couple of books have just arrived from teh interkittens, so I will read some of those and then forget to write anything down. But first, I’m going to ramble on with a long, poorly-referenced bundle of ideas which really need some proper thought. I should really have written about women in jazz history, shouldn’t I? But this is an interesting topic, and one I keep coming back to in my own reading. When I get done with two of my new books, I’ll have some more cleverly thought out things to say. But for now, here’s a big ramble.

I’ve also wanted to comment on Peter’s Jazz and the Italian connection post because it touches on some issues that I’ve thought about for a while. And that are bizarrely relevant to Australian mainstream politics at the moment.

To sum that one up, I’m not suggesting that this is what Peter is doing (because the man knows his shit), but I do think it’s misleading to argue that the exclusion of the ODJB was a consequence of ‘reverse racism’ or ‘political correctness’ favouring black artists. Which is what is argued by a number of truly dodgy scholars in jazz studies (I’m going to have to check my notes more thoroughly for those references – bare with me, k?)

From what I can tell, however, Peter is arguing something slightly different: that it is important to discuss the ODJB in a history of jazz. For all sorts of reasons. I’d certainly agree.

My interest would be in how the ODJB presented a more palatable ‘white’ jazz to mainstream audiences at the same time as race records (labels targeting black audiences) were selling ‘black’ jazz to ‘black audiences’ and live music venues were also presenting jazz in quite racialised terms (the Cotton Club itself is a good example – black musicians presented for white audiences). As Peter also implies, the ‘white’ and ‘black’ dichotomy isn’t all that useful. The Italian musicians (and French and… everyone else) were definitely ‘othered’ at the time – they weren’t ‘white’ (ie Anglo celtic), but they read or looked white, and that was important when the look of an artist was being established as a key marketing tool. So my question would perhaps be ‘What was to be gained by, and what were the consequences of making the ‘otherness’ of non-anglo celtic musicians invisible in jazz histories?’

What I think happened is that the favouring of black artists was a consequence of racism in the 1930s and 40s. In those moments when ‘the origination of jazz’ was first being written (by white authors) the ‘popular jazz press’ (ie newsletters, magazines, etc) and other writing about jazz favoured black musicians because this approach favoured myths about race and creativity.

Just like the Ken Burns ‘Jazz’ doco, this approach follows particular individual musicians, positioning them as unusual, almost magical figures who overcame poverty/geography/BEING BLACK because they were somehow touched with a magical gift. In reality, these few figures were hard working people who worked within black communities, and then the wider American culture, experiencing racism every day. Their skills weren’t ‘god given gifts’ but the fruits of hard labour as well as talent and community support, and the advantages of being male musicians in an industry that made it very difficult for women to get gigs. This is something George Lipsitz discusses in his work “Songs of the Unsung: The Darby Hicks History of Jazz.”

This approach to jazz history – telling stories of miraculous black achievement as an aberration from the norm – reinforces racist archetypes. If the stories were told as stories of hard work, the musicians positioned within communities which fostered and encouraged their creativity – the authors would have to revise their ideas about black and white creative practice. They’d have to accept the idea that musical genius happens in all communities, regardless of race or class or gender. But that the factors which make it possible to realise this genius are absolutely defined by class and privilege and power and opportunity. Here’s a long quote from Lipsitz discussing these things:

The story of jazz artists as heroic individualists also overlooks the gender relations structuring entry into the world of plying jazz for a living. Women musicians Melba Liston, Clora Bryant, and Mary Lou Williams can only be minor supporting players in this drama of heroic male artistry. Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday are revered as interpreters and icons but not acknowledged for their expressly musical contributions. Although [Ken Burns’] Jazz acknowledges the roles played by supportive wives and partners in the success of individual male musicians, the broader structures of power that segregated women into ‘girl’ bands, that relegated women players to local rather than national exposure, that defined the music of Nina Simone or Dinah Washington as somehow outside the world of jazz are never systematically addressed in the film, although they have been investigated, analyzed, and critiqued in recent book…” (15)

The ODJB was one of a number of white bands working at the time, and they were well positioned to take advantage of a new recording industry and the possibilities of clever promotion. I think that they are/were glossed over by many music historians not because they weren’t black, but because they didn’t shore up racist archetypes.

The other interesting part of Peter’s post discusses the role of Italians in the early days of recorded jazz (and jazz history). This is much more interesting. There’s a chunk of scholarship about discussing the role of jewish musicians in early jazz and radio, which I think can be helpful. And cities like New Orleans (and New York for that matter) had large migrant populations: jazz is (as Winton Marsalis goes on about, ad nauseum), a gumbo. It is a mix of cultures and musical traditions. So it makes perfect sense to explore the Italian contribution.

Lipsitz, George. “Songs of the Unsung: The Darby Hicks History of Jazz,” Uptown Conversation: the new Jazz studies, ed. Robert O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, Farah Jasmin Griffin. Columbia U Press, NY: 2004: 9-26.

Oh, argh. My life is making it difficult for me to find time to do proper service to these posts. And I’m a little tired of just defaulting to women singers. I’d really like to post some women record company administrators, or composers or other people in the music industry. But I guess that’s the point of this whole project: women in music have always found it hard to get into roles other than ‘songbird’ or, at the most, ‘songbird with piano’. A recent Riverwalk Jazz story ‘Not Just Another Pretty Face: ‘Girl Singers’ of the Swing Era’ almost does some solid gender talk in its discussion of women singers in the jazz age.

Incidentally, I’m sorely disappointed by Riverwalk’s only managing to do TWO shows about women in women’s history month. And after those, it’s back to the dick stuff. PLEASE, if I can manage to come up with around sixteen women musicians, surely one of the most famous, most prestigious jazz media can come up with more than two measly stories?

In researching jazz history I’ve come across some really interesting discussions of how particular instruments have been gendered. Krin Gabbard published an article in 1995 called “Signifyin(g) the Phallus: Mo’ Better Blues and Representations of the Jazz Trumpet,” (Representing Jazz, ed. Krin Gabbard. Duke U Press: Durham and London, p 104-130) which discusses the way trumpets functioned, discursively, as phallic imagery. Well, duh. This is partly why Clora Bryant is such an interesting example: woman with trumpet! OMG WIMMINZ HAS THE FALLUS!!! JAZZ IS RUINED!11

Linda Dahl goes into the gendering of musical instruments in Stormy Weather: the Music and Lives of a Century of Jazz Women (Limelight: NY, 1992). I don’t have the book right here in front of me (must buy!), but my notes remind me that she discussed the way music was ubiquitous in domestic life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and that this music was ‘home made’. Playing the piano and singing were considered essential parts of a young woman’s development, and were also often positioned in faith contexts – women played the piano or organ in church. Dahl also discusses the way the music industry was very difficult for women to get into, particularly for white women instrumentalists, how the musicians’ union was obstructionist in women’s careers, and the way territory bands were more accessible than mainstream bands. None of these things should surprise us. Indy rock has seen more women musicians than the mainstream (though they seem to be relegated to drums and bass rather than having access to the ultra-phallic lead guitar), and I’m still chasing down ideas about unionism and social power.

So Sister Rosetta Tharpe is an interesting figure. She played the guitar. She mixed church music and blues (shock!), she was a composer, a singer, a solo artist, a musician in a big band (Lucky Millinder’s, most notably), she pwnd all.

I’ve talked about Rosetta Tharpe before. Once as a Thursday cat blogging post, another as a discussion of how the way her guitar tuning was marked by race, class, geography and (implicitly) gender, in Retuning for white audiences – more sister rosetta tharpe.

It’s cool to compare this pretty explicitly sexualised image of the female form (Lonesome Road, with Tharpe singing with the Lucky Millinder band in 1941):

with this video of Sister Rosetta Tharpe singing ‘Up Above My Head’ with a gospel choir, 1960s). Dang – sister is workin’ that power. Safely contained by religion? I don’t think.

(via flopearedmule)

Eve Rees and her Merrymakers were an all-female dance band from Australia. They were very popular, touring extensively in rural and city Australia in the 1920s and to a lesser extent in the 1930s. Despite their popularity, it’s hard to discover much about them. A dodgy Trove search gives only three hits, and much of what I’ve found comes from books. I know! Today is World Book Day, so it’s appropriate It is not actually world book day, but that’s ok – we shouldn’t wait for WBD to read books :D . In fact, this image (of Eve Rees and her Merrymakers, including Grace Funston, Alice Dolphin, Marion de Saxe, Eve Rees (middle aged woman in centre), Stella Funston, Alma Quon, Gwen Mitchell and Lorna Quon) is taken from the book I’m about to discuss.

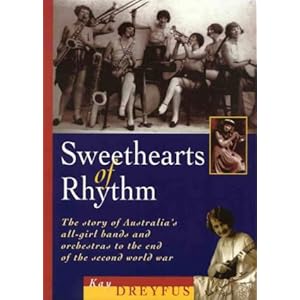

I totally forgot to do a post yesterday (yeah, yeah, whatever), so today is something special. A dear friend of mine, Corinne, gave me this book a few years ago:

(Sweethearts of Rhythm: the story of Australia’s all-girl bands and orchestras to the end of the second world war by Kay Dreyfus (Currency Press, Sydney, 1999))

It’s all about Australian all-women bands during the wars. The most famous of these sorts of bands is of course the American International Sweethearts of Rhythm. But there were actually heaps and heaps of these all-women bands in Australia and other countries. Mostly because so many men left for war there simply weren’t enough left behind to fill all the bands playing for the hundreds and hundreds of live music venues all over Australia. Remember, dancing was one of the most important popular entertainments during this period.

But all-women bands also served as titillation for male audience members, and initially as novelty acts for the broader community. Despite these issues, there is no doubting the competency of many of the all-women bands during the jazz and swing eras. After all, the mainstream jazz industry neglected 50% of the musicians on the basis of their sex, so 50% of that population were available for work when the labour pool shrunk.

Eve Rees and Merrymakers were one of the better known Australian all-women bands, managed by Rees, a capable and energetic business woman. Dreyfus quotes Alice Dolphin (who went on to lead her own bands):

The Merrymakers’ dance band at that time was extremely popular and I was invited to join them. The leader of the band was Mrs Evelyn Rees, a charming middle-aged woman who was well-liked everywhere we went. She was just ideal for the job.

What a tremendous amount of work we got! Every night, Mayoral balls, Country Women’s Association dances and balls (this of course meant travelling to country towns), Cafes, Lodges, Clubs, Weddings, Birthday parties, Jewish Greek and Chinese dances, Bar Mitzvahs, twenty first birthday parties and just parties, Military and Air Force dances and receptions of all kinds.

There’s more to be read about the Merrymakers in Dreyfus’ book, and I recommend picking it up.

References

You can read about the popularity of cinema and dancing in: Matthews, JJ, Dance Hall & Picture Palace : Sydney’s Romance with Modernity, (Sydney: Currency Press, 2005).

The Jeannie On Jazz blog proved useful in putting together this post.

Dreyfus has also written ‘The Foreigner, the Musicians’ Union, and the State in 1920s Australia: A Nexus of Conflict’ an interesting article about the role of the musicians’ union in the banning/boycotting of ‘foreign’ (ie non-British, ie non-white) musicians. This of course is relevant to recent talk about the Sonny Clay band and its role in provoking the ban on black musicians. And the Sonny Clay band was mentioned in the latest (third) episode of the Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries’ abc tv series set in the 1920s.

(image lifted from wikipedia)

I’d never heard of pianist, composer, bandleader Billy Tipton before I was sent an email recommending him for this series of posts (I’ll leave that kind correspondent to out themselves in the comments if they like.) Everything I know, I’ve scrounged online.

Basically, Billy Tipton was born Dorothy Lucille Tipton in 1911, and was a keen pianist interested in a life in jazz. By 1940 he was living as a man, binding his breasts and otherwise dressing and identifying as male. It wasn’t until he died in 1989 that Tipton’s family discovered he was assigned female at birth.

I don’t know the exact reasons for Tipton’s living as a man, but I want to include him in these Women’s History Month posts because he draws attention to the limits of single definitions of masculine and feminine. And one of the clearest points to be made about Tipton’s story is that living as a woman musician limited (and limits today) your profesional opportunities.

It’s women’s history month again, and I’m listing a different woman musician from the first half of the century every day (as I explain here). Last year I did a different woman dancer every day, and that was super great fun. I’m enjoying the women musicians, but I haven’t really had a chance to research or push myself, as I’ve been away at a dance event for most of this month. And today, I’m still feeling a little tired and rough, so I’m not really ready to push myself. Tomorrow. Tomorrow.

I did decide in that first post of the month that I’d only dance as a lead this month, as a way of exploring International Women’s Day and Women’s History Month and what it means to be a woman dancing. Well, actually, I just decided that on a whim, without much thinking at all. I don’t follow much these days as I’m really trying to get my leading up to snuff, and the best way to get better at dancing is to dance. And as every lead knows, the real challenge comes on the social dance floor, when you need to come up with a series of moves, connect with your partner and attempt some sort of creativity all at the same time.

We won’t even mention the battle to maintain the fitness and aerobic capacity lindy hop demands.

I have to say, it hasn’t been hard, because I get to dance with amazing dancers, most of whom are my friends. And I’ve learnt so much in the past month or two it’s kind of scary – I suddenly find myself stretching and expanding my skills, pushing myself to try things that I’d never have tried before. But it’s certainly meant a bit of rethinking the way I operate socially at exchanges and dance weekends. My weekend pretty much felt like this:

I mean, the biggest change for me this past weekend in Melbourne was simply spending very little time with men. I have lots of lovely male friends, but I only danced with two of them this weekends, and I discovered that I just didn’t end up spending as much time catching up with blokes as I usually do. :( I think that’s mostly because I’d be chatting to some chicks, and then a song would start and one of them, or I would say “let’s dance!” and then we would, and then afterwards I’d end up mixing with chicks and chatting. Rinse repeat. This of course means that the men in the dancing scene need to man up and start with the following, because I refuse to miss out on their dancing wonderfulness! Good thing Keith and I got to DJ together, or I’d hardly have spent any quality time with a bloke at all this weekend. And that is UNACCEPTABLE.

Workshops on Sunday were fun. I learnt a LOT. And I did a private class with Ramona on Friday, which kind of broke my dancing for a bit, and then suddenly it all came back together and I was a dancing machine on Saturday night. Blues dancing: still a bit too dull for me atm. But then, only boring people are bored, and that’s doubly true of dancers – only a boring lead is bored. I need to woman up.

The DJ Dual with Keith went really well. In fact, I had the most fun DJing I’ve had in ages and ages. We ended up trading three songs until the last moment when we played alternative songs. I think we would have liked to continue for another hour or so, trading single songs, as we got more confident and figured out the skills and tactics we needed. But we’d been DJing for an hour and a half by then, so we might’ve gotten a bit tired. And I had to go in the jack and jill, and I’m not sure it would have been ok for me to DJ the competition I was in. Overall, it was nice to have a bit of a challenge, and it was nice to work with a friend I like and have lots in common with musically. But he is a bit of a sly dog, and wouldn’t tell me what he was playing next, most of the time, so I had to keep on my toes. But that was actually even more fun. DJ Dual: LIKE.

NB There were THREE women leads in the jack and jill competition, and one got through to the finals (in a group of six leads)!!11!1 That photo above is one I lifted from Faceplant – sorry I can’t remember whose it was. It’s of the J&J, I’m in there, and so is at least one of the other female leads.

Now: NEED MORE MALE FOLLOWS!!!

I ended up catching up with lots of internet friends over the weekend as well. Which is always a bit of a push, but well worth it. The best part was walking into a cafe, saying “Hello, I’m Sam, nice to meet you!” and then barrelling into an hour of solid, hardcore talking as though we’d known each other for years. Which we have, really. Just not in person. This trip I went for smaller catch ups, rather than bigger groups, because I wanted to get a chance to actually connect with everyone and I often don’t get that at bigger meet ups. But that also meant I didn’t get to see everyone I wanted to. Oh well, good thing I go to Melbourne regularly! I’m planning another trip in May for the Frankie Manning birthday celebrations, so I’ll see if I can fit in the people I missed this time. But that sucks, because you’re still missing people! And then there are all the dance people I want to see off the dance floor! This is, of course, why exchanges are so much fun and so challenging – so many friends descend on one city for just one weekend you really need an enormous dance floor to connect with them all!

Righto, I’d better write up today’s jazz woman!

I’m a bit pushed for time today, as I’m in the middle of a dance weekend, but, well, I’m also hardcore. I’ll look up some less well known women later in the month when I have more time. :D

Blanche Calloway was Cab Calloway’s older sister, and was a musician, bandleader and composer in her own right.

This is a song she composed and recorded in 1934 with her male band the Joy Boys: