[edit: I wrote this almost a month ago but have been sitting on it.]

I’m not going to rave and shout about this album Chasing Shadows by Melbourne band Ultrafox, because this is not that type of album. It’s more thoughtful. While the tempos get quite quick, the energy feels more complex and intricate. It feels very much like the difference between lindy hop and balboa: it’s hot and fast, but you wouldn’t sweat, because you are too cool. This is a jackets-on, nice-dress type of album.

Having said that, ‘Vette’ opens the album with a supersweet bass intro that makes me want to leap up and dance. And I’m not one for nice-dress, jackets-on, cool and sophisticated dancing.

I should stop for a second here, to say, once again, that I was offered a copy of this album by Peter Baylor, in return for writing a review. You know I can’t say no to free CDs, and it’s a genuine pleasure to listen to Australian music and talk about it online. It’s even nicer to develop relationships with the musicians I get to dance to (dance with – we are together, in these moments, musicians and dancers) at events around the country.

So, to be clear, this is a solicited review. And, again, I had a moment of worry when I agreed to this deal. What if the CD sucked? And then I gave myself a talking-to. Look at the people on this album: Peter Baylor, Jon Delaney, Kain Borlase, Julie O’Hara, Andy Baylor, Michael McQuaid. Do you think it’s likely it’ll suck? No. It won’t suck. It doesn’t suck.

Peter Baylor leads Ultrafox, and even here in Sydney I’ve had a bit of a big Baylor week. My copy of Chasing Shadows arrived this week, and I saw Andy Baylor launching his CD Down Where the Banksias Grow at the Petersham Bowling Club last night. The Baylors are pretty important doods in the Melbourne (hells, Australian) jazz and acoustic music scene. When I say acoustic music, I mean the sort of music that doesn’t use a lot of amplification. Not that I’m against amplification, but this stuff has its roots in the days when a band had to shout real loud to be heard in a crowded bar rather than just twiddle a dial. Anyways, if you’re into jazz, blues, old timey, western swing… all that sort of stuff (as I am), then you’ll probably have heard of the Baylors.

Dancers who’re into Australian jazz will also have heard of Michael McQuaid, saxophonist, clarinetist, leader of The Red Hot Rhythmakers, The Late Hour Boys…etcetera, etcetera. Boy got chops.

If you’ve been dancing in Melbourne to a live band ever you’ll indubitably have heard Julie O’Hara sing. I remember talking to Julie at the 2006 Melbourne Lindy Exchange the day after Anita O’Day passed away and suddenly realising ‘Anita O’Day! Of course!’

And even I recognise more of the musicians in this band, though I’ve not been in Melbourne for four years now. Ultrafox: good, well-seasoned, skilled musicians. This is going to be good.

Ok, enough of that. Let’s get back to the music. And I’m going to talk about this as music for dancers and dancing. Because, for most dancers, the music is the thing. They’re unlikely to run up to the DJ and ask who was playing guitar on that last track. They’re more likely to let you know they dig a song by running about like crazed adrenaline junkies. Unless they’re balboa dancers. Balboa dancers never look like they’re in a hurry.

Even though Balboa developed in ballrooms with big bands (if you’re interested in this, you need to watch Peter’s great talk about balboa history), there’s something about the complexity of manouche which really suits this tiny, intricate, complicated dance. While lindy hoppers tend to be a little on the meat and potato side of things, balboa dancers are more discerning. They can dance super fast, they can handle the fact that manouche rarely (if ever) features a drummer, and they’re all up in Django’s business.

I’m going to keep returning to the balboa dancer as audience for this band because there’s a long association between balboa and gypsy or manouche jazz in Australia and overseas. There aren’t a lot of Balboa events in Australia (just one at the moment) and that one has hosted Mystery Pacific more than once. Duck Musique from Melbourne also have cred with balboa dancers.

There are, however, about a million second rate gypsy jazz bands around the world. So I’m always a little sceptical when faced with yet another Hot Club of Blahtown recording. But Chasing Shadows is solid stuff. Here, let’s get into the nitty gritty: dancers really just want to know which songs to buy from a particular album.

Firstly, Chasing Shadows covers a range of styles. Totally right-on when you consider the history of manouche, the importance of a waltz and what I’d (clumsily) call ‘Latin rhythms’. But lindy hoppers and balboa dancers aren’t really into that action. Having said that, ‘The Ruby and the Pearl’ on this CD is probably my favourite track. Couldn’t DJ it, do play it regularly for my own non-dancing pleasure. So if you’re flicking through song samples, don’t stop at just one song – the breadth of styles is one of this album’s strengths.

I would totally DJ ‘Vette’ for dancers. I was charmed by the clarinet, lighting up all that strummy-strum-strum string action which makes for such solid dancing. The balance of grounding rhythm (which dancers really do need), lighter melody and instrumental flourishes makes this super nice. Listening to Andy Baylor last night, with this CD in mind, I thought to myself “Really good musicians really do make a difference.” Manouche isn’t for babbies; if it’s good, it’s hard. I see a lot of very ordinary… shitty musicians at dance gigs, but I would pay extra for these guys. I would hire them for a gig. I would DJ this album.

I also really like ‘High Flyer Stomp’. It has that lighter edge, but with a really solid rhythm – the stuff dancers need. I’m also a total fool for a bit of fiddle. I think it’s the way it joins up all the spaces between the beats to really flesh out the swing that makes what we do jazz dancing. Or swing dancing :D

I guess what I’m saying here is that the instrumentals on this CD are really really good. This is where these guys truly shine. I think they have the best cross-over value for non-Australian DJs and dancers. But that’s mostly because I still stumble when I come across Australian vocals in jazz. I think this is parochialism on my part, and I need to get over it. Think of Eamon McNellis. Think of Hetty Kate. Heather Stewart. Australian voices, marked by the intonations and rhythm of Australian English, but very fine Australian voices. And I think Andy Baylor makes very powerful arguments when he talks about the vernacular in jazz. Or about looking for Australian folk music. I’ll get over this. With the help of artists like these.

What else would I play for dancers?

There’s a version of ‘Minor Swing’ here too. Yeah, yeah, I know, most of us are totally over this staple of the balboa/gypsy jazz repertoire. But I’d have a listen to this one – the vocals are interesting, and make for more stimulating dancing than you’d expect. I’d definitely DJ this one. The intro catches the ear, the rhythm is nice and clear enough for even the newest dancer, and Julie does some of her best work on this song.

‘Swing 39’. Another staple. Would DJ.

…look, it seems I’d DJ quite a lot from this CD. Especially the uptempo stuff. But there are other, really pretty songs like ‘Royal Blue’, which I’d play for lindy hoppers or at a quieter moment in a dance.

To sum all this up, I’m very glad I have a copy of this CD. It’s lovely. And I will DJ from it, and I’m pretty sure I’ll score big time with dancers. Oh yeah, giggedy piggedy. Hoorah for bands making good music and recording it so we can share it with our friends. Hoorah.

The only problem with this album is that you can only buy it in person from Peter Baylor at gigs at the moment. So if you’re in Melbourne, keep an eye out for him. If you’re elsewhere, drop Peter a line stringbuster@pacific.net.au and hassle him for a copy. It’s definitely worth the effort.

I’ve recently discovered the 1951/52 stuff by the Johnny Hodges band on this dodgy digital download album

I’ve recently discovered the 1951/52 stuff by the Johnny Hodges band on this dodgy digital download album  The Never No Lament: the Blanton Webster Band 3CD set was one of the first serious Ellington CDs I ever bought (though it was a lot cheaper then than it is now), and I bought it because dancers and DJs I admire recommended it on the

The Never No Lament: the Blanton Webster Band 3CD set was one of the first serious Ellington CDs I ever bought (though it was a lot cheaper then than it is now), and I bought it because dancers and DJs I admire recommended it on the  I used to have a long bus commute to uni which I’d spend reading my way through Gunther Schuller’s book The Swing Era: the Development of Jazz 1930-1945 and listening along with my whole Ellington collection on my ipod. I read music (haltingly), and Schuller spends quite a bit of his time examining scores in detail. I’m not entirely convinced by everything Schuller says, but Schuller’s is an interestingly scholarly approach to a musician who was as comfortable with concert halls as dance floors.

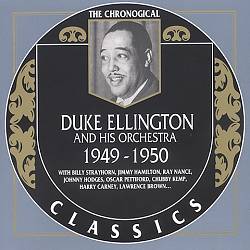

I used to have a long bus commute to uni which I’d spend reading my way through Gunther Schuller’s book The Swing Era: the Development of Jazz 1930-1945 and listening along with my whole Ellington collection on my ipod. I read music (haltingly), and Schuller spends quite a bit of his time examining scores in detail. I’m not entirely convinced by everything Schuller says, but Schuller’s is an interestingly scholarly approach to a musician who was as comfortable with concert halls as dance floors. Most of my love for Ellington is centred on his earlier stuff and on those small group recordings. My interest tends to wane at about 1950, to be honest, but that’s not a strict rule. There’s a song called ‘B Sharp Boston’ which Ellington recorded in 1949 and which used to get around on those dodgy ripped compilation CDs as ‘Sharp B Boston’. I picked up the Chronological Classics Duke Ellington Orchestra 1949-1950 CD in about 2006, and discovered it was actually called ‘B Sharp Boston’, and that there was a bunch of other great stuff on that CD that makes for top DJing (I’ve written about this before in

Most of my love for Ellington is centred on his earlier stuff and on those small group recordings. My interest tends to wane at about 1950, to be honest, but that’s not a strict rule. There’s a song called ‘B Sharp Boston’ which Ellington recorded in 1949 and which used to get around on those dodgy ripped compilation CDs as ‘Sharp B Boston’. I picked up the Chronological Classics Duke Ellington Orchestra 1949-1950 CD in about 2006, and discovered it was actually called ‘B Sharp Boston’, and that there was a bunch of other great stuff on that CD that makes for top DJing (I’ve written about this before in