Why do I go back to Herrang?

I’m going to assume that you know what Herrang dance camp is, and that you have some passing familiarity with concerns about the enterprise. People who know me are surprised that I keep returning to an event that seems to break all my personal and professional rules. Why do I keep going back, trying to be useful and to contribute to constructive political work at this huge, rambling pile of a dance event?

Why do I go back each year?

It’s a huge enterprise. 300 odd paid staff + volunteers + 20-odd DJ + dozens of musicians + dozens of teachers, over 5 weeks of camp programming, and two additional weeks of set up and bump out in a small village in rural Sweden.

There is no other event like it in the world.

Buildings need to be cleaned, food cooked, classes taught, music played, bills paid, cars driven, sound gear fixed, dance courses administered, classrooms booked, dance floors built and repaired, sets built. For 7 weeks. Each week a new group of staff needs to be inducted. A huge, volunteer and largely untrained staff. Managers start from scratch, with staff of varying ability and inclination.

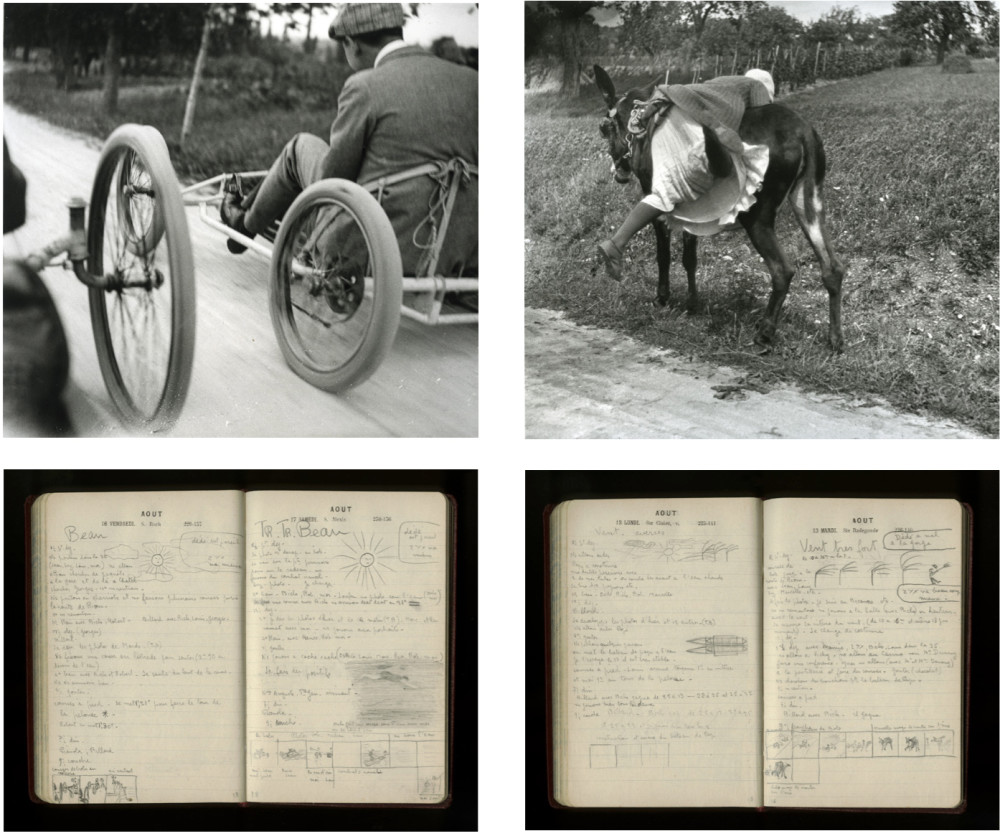

Because it’s the only long term event in the world, we get to see processes and ideologies play out in real time, in a durational sense. We see the usual tensions of late nights and high adrenaline play out over a longer time. Which means that we see things that we don’t at other events. We see how humans from a range of cultures and language groups interact with each other in a pressure cooker environment. Structures or systems that might be stable over a weekend or a just a week might not remain stable over 5 weeks. Ideas or processes that work for 3 days with a staff working to the brink of exhaustion show cracks over longer periods, where staff must begin thinking about care, rest, recuperation, down time. All elements that don’t come into play at other dance events.

Sexual harassment and assault are symptoms of power relationships and dynamics between individuals and within groups of humans. They aren’t inevitable, but they are characteristic of patriarchy. They can be managed and eradicated, but only through concentrated, strategic planning and policy. And most of this work is conducted by inexperienced ordinary people. This work is increasingly professional and sophisticated. I often wonder, though, if the codes of conduct and safety policies of American events, for example, would stand the test of a five (or seven) week time frame. They are, essentially, experiments in social politics, and working largely against the broader patriarchal culture of their home societies. Would Lindy Focus’s exceptional approach to sexual violence remain steady over five weeks? I think that it could, perhaps, but it would require a lot of on-the-ground, real time adjustment and tinkering. Because shit changes over time.

While Herrang does not have an over-arching code of conduct or safety policy, each of its many departments _does_ have a particular set of rules and guidelines for determining how staff and volunteers should treat each other and the general campers. As DJs, for example, we were reminded again in week 3 that drinking to excess while DJing is not ok. That we have to treat fellow DJs with respect and professionalism, by turning up on time for our sets, checking in with our DJ peers, and being supportive of their work. We were reminded of emergency procedures and shown how to use the emergency phones placed around the camp.

Each of Herrang’s departments change staff each week, so the managers and more permanent staff have the opportunity to edit, change, and adjust processes to respond to their participants’ changing needs. And the work of training and enculturating an entirely new group of people each week.

This agile people management is the most fascinating part of Herrang. Shane and Spela are juggling hundreds and hundreds of staff members across hundreds of roles. They are dealing with changing and unpredictable conditions (too many campers! a water shortage! disease! excessive heat!) within a framework that has to be reflexive and responsive. It’s a truly impressive thing to see in action.

These staff coordinators manage a base of general staff and volunteers, but work through and with a group of department managers. Each of those managers juggles a 24 hour schedule and a shifting group of workers of various skill, ability, and inclination. If you thought it was difficult managing entitled middle class white men on the dance floor, imagine trying to get them to work hard in an industrial kitchen for a black woman manager.

One of the primary concerns of the staff coordinators and managers is morale. How do you keep so many people feeling good over a long period of time under difficult circumstances? They don’t sleep enough, they don’t eat properly, they’re saturated in endorphines and adrenaline, and they’re doing unfamiliar work. How do you keep the whole machine running?

Herrang has a broad system of processes for handling these issues, from staff appreciation parties to balanced shift lengths and times, and a fairly efficient process for handling complaints, concerns, and questions. It is certainly not perfect, and it has flaws. But not because no one is trying. The staff managers and coordinators are caring people, and they work hard to improve processes every year. They’re also clever and inventive. Because they are also jazz dancers :D

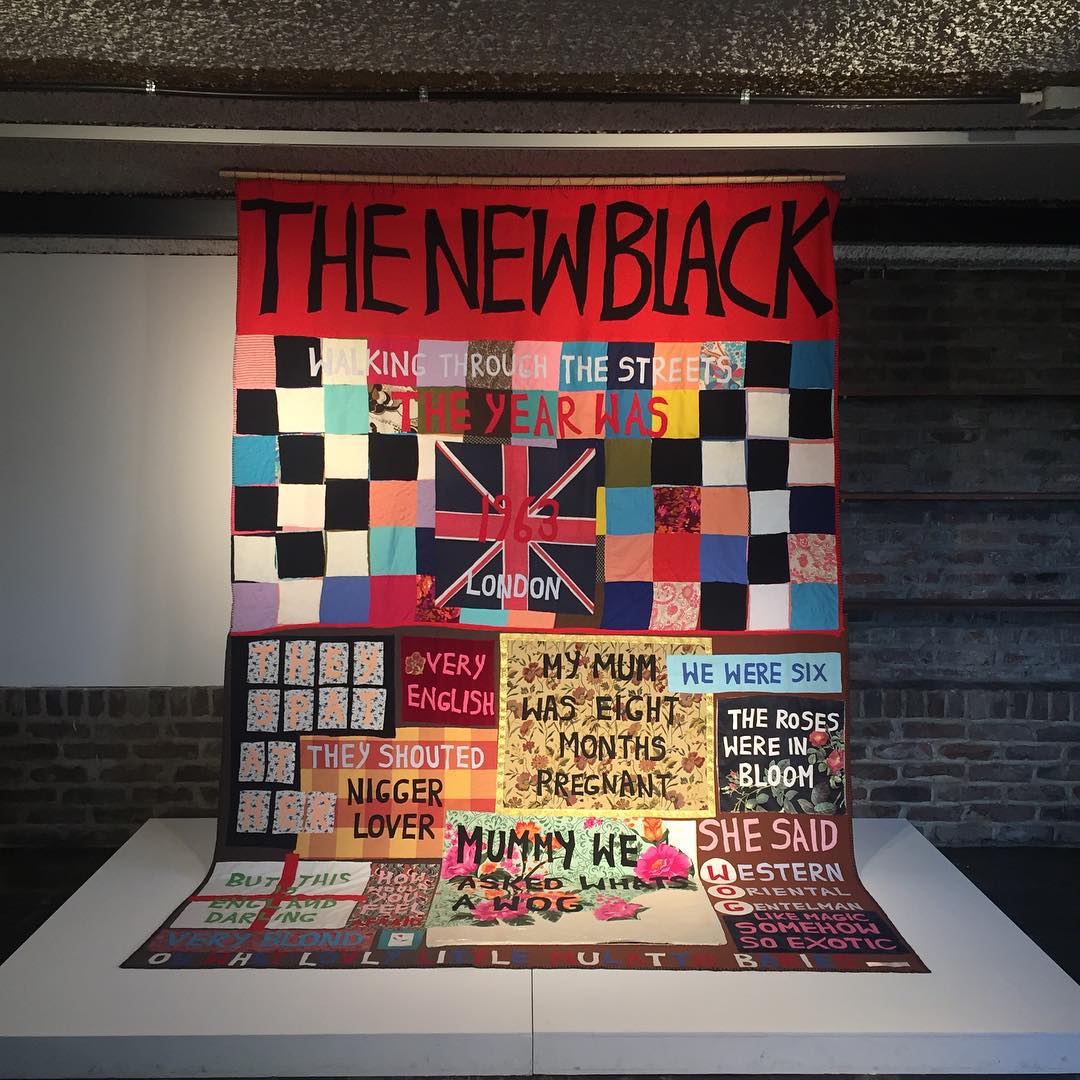

What I’ve noticed about Herrang, is that the more permanent staff (people who are there for more than two weeks) tend to be curious, inventive, industrious, cooperative people. To the point of obsessive. Living in the countryside for 7 weeks, they start making things. Inventing things. Experimenting with things. While a conventional office workplace might foster pranks, Herrang staff move beyond your random ‘wrap a car in toilet paper’ prank to ‘wrap every item in the camp in toilet paper’. They come up with brilliant ideas, but then they truly relish figuring out how to execute these plans, and then do so within a contracted time span and limited resources. Someone might decide that the theme for this party is ‘Savoy’, and by the end of the day, staff have build an entire New York neighbourhood out of cardboard, wood, and fabric. A woman might have lost her phone, and by the end of afternoon, staff have built a human sized phone, put a jazz band on a truck (including a piano) and moved the whole thing across the village to her dinner table where she’s serenaded by her friends and peers. And giant phone. Someone else finds a giant glowing model moon, and by the end of the week she’s not only suspended above the square, she’s lit from within with a suspended table and chairs beneath her to be enjoyed by dining lovers.

This is the part of Herrang I like most. It’s exciting. It’s stimulating. Over-stimulating. I really enjoy real-time problem solving at the best of times, but on this scale it’s invigorating. Thrilling. Dangerously addictive.

I really like working with such a clever, creative group of people from all over the world. They manage language differences, tiredness, negative budgets, and sexual tension with enthusiasm and professionalism. And good will. Yes, people crack the shits and get overtired. But they also laugh a lot every day, and seek out ways to delight each other.

They’re also some of the kindest, most generous-hearted people I’ve ever met. One of the most common things I see and hear in the camp is a person going to great lengths to find out what their colleague likes best, hunting it down (even going driving hours to find it), then surprising them with it. Just because they looked tired or a bit sad. Or because they love them. Yes, there are pranks, but they aren’t cruel pranks. They’re loving, affectionate pranks. Filling a new teacher’s classroom with balloons for their first class. Swapping wardrobes with another dancer for a day. Learning an entire, complex jazz routine in a day, then recruiting a jazz band to surprise someone with it in their office at lunch time. Organising a parade of children and adults playing musical instruments and wearing costumes to tramp through the camp, just to entertain the participants and audience. Leaving a punnet of perfect strawberries on a colleague’s desk, because you know they are lovely.

And on top of all that, they love to dance and sing. To eat and cook and make love. To work hard and sleep deeply. To argue and talk and laugh.

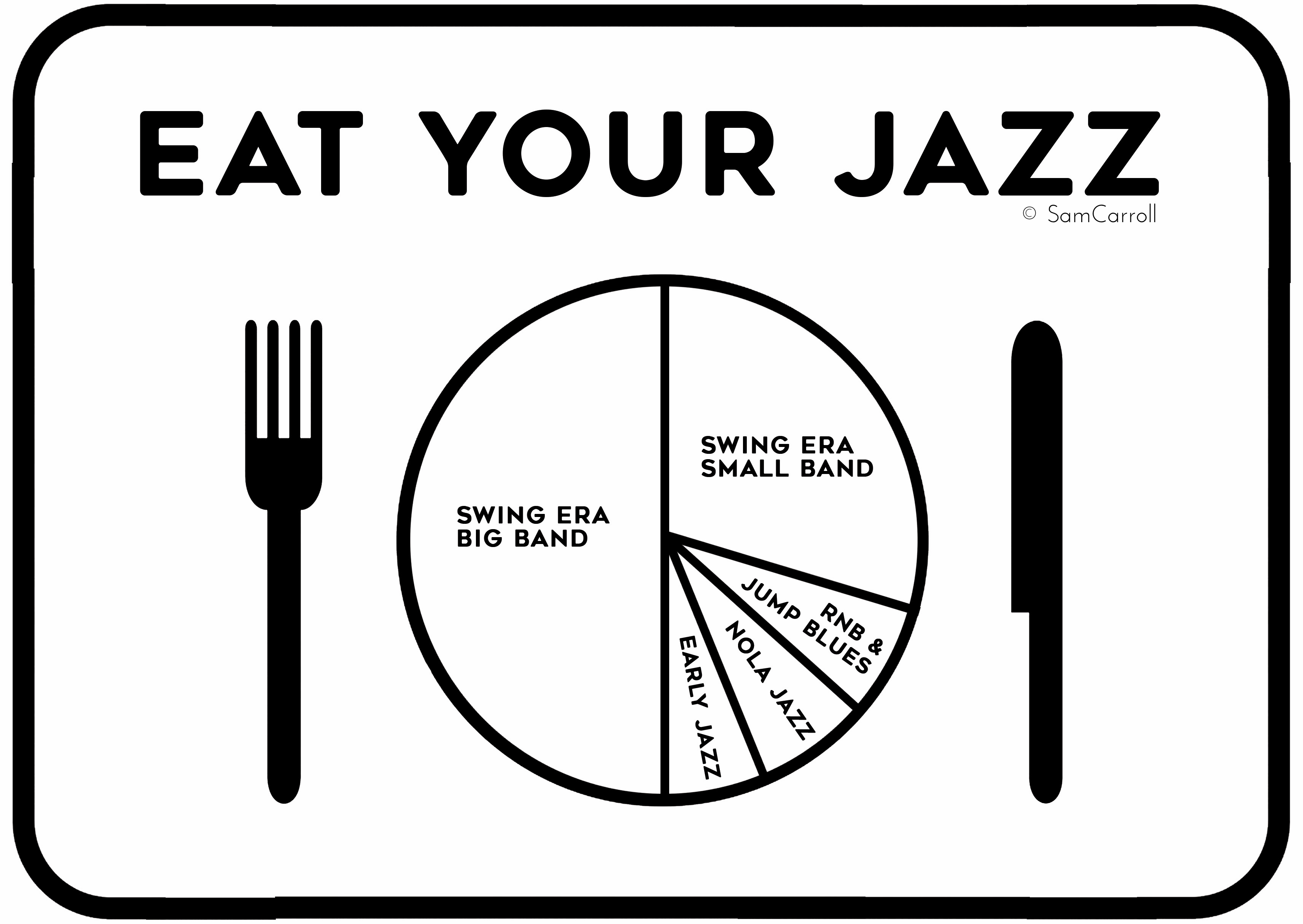

These are the reasons I, personally, go back to Herrang. I like to spend my days visiting people’s offices, learning about their work, seeing how they do things. Watching people be kind and generous. Laughing til I can’t breathe.