Jonathan Doyle Swingtet – Too Hot For Socks

and

Michael Gamble and the Rhythm Serenaders – Michael Gamble and the Rhythm Serenaders

Disclaimer: Books Primo approached me to review the Doyle album, offering me a free download. I chose to pay for it (to support the band), but i took him up on the invitation to review. I saw it as an invitation to engage with his music, to share my opinions. The Gamble review, however, is unsolicited.

Both of these albums landed in my collection on the same day, both prompted by updates and dancers’ chatter on facebook. That in itself is an indication of how closely these two bands are connected to the lindy hop scene. And the importance of digital technology in securing the success of a modern jazz band. You have to have a) a good online vendor for download sales, and b) good social networks in the international lindy hop scene to promote your album by word of mouth.

Both of these bands are American, and both play for dancers, and that’s the other side of the securing-success equation. If dancers see and hear you playing live, and if they feel your feels, and if you’re looking up, at them, engaging with them, and doing that creative, collaborative improvisation that makes jazz jazz, then you’re going to develop a reputation that will help you sell albums and book gigs.

Right now I’m a zillion kilometres above the ground (still over my own continent, though), so I don’t have access to any other information either band. So stick with me, k?

These are dance bands, peopled by, and designed for dancers. Michael Gamble is a dancer and DJ, and his band includes dancers. He also manages the DJed and live music for Lindy Focus, an event fast becoming known for its live music – both in the ballrooms and in the informal jams. Jonathan Doyle is also closely connected with dancers, his band including Brooks Primo and others. Doyle, in fact, has recorded with Tuba Skinny, the Fat Babies, and most recently with Naomi Uyama’s Handsome Devils. All big names in the jazz dance world.

Both bands play regularly for dancers, and are prominent on the american dance event calendar. I’ve never seen either live, though I’m familiar with their recordings, know band members, and have DJed their work before. While they exist as real live people and musicians in American dancers’ lives, they are online people for me. Online friends. I won’t hear them play live unless I travel to America, something I’m not likely to do in the immediate future (guns, Trump, scary arse customs processes, etc). So I consume them as recordings.

For many American dancers, though, they are living, breathing people, friends they see on the stage from the dance floor. Friends they dance with on the dance floor. I think that this relationship is very important, and we all know that live music is now, more than ever, at the core of what we do as dancers today. There was that moment where bigger scenes focussed on DJs, while smaller scenes always maintained relationships with bands, when they had them. But now we are all about live music. And customising bands for our consumption.

Peter Loggins recently noted in a talk at Swing Castle Camp that DJs have both shaped and been shaped by dancers’ preferences, playing 3 minute songs in the 120-180bpm, swing-only, comfort zone. And this has shaped dancers’ expectations of live music. I’m not entirely on board with this argument, as there are plenty of scenes where DJs are playing more varied sets, and plenty of scenes where dancers gather at live music gigs because that is all they have for social dancing.

I’m also more interested in how a contemporary ‘dance band’ might have been shaped by these experiences with DJs. Do modern lindy hop and balboa bands consciously play in ways which reflect this ‘perfect’ dancing storm? If Loggins is right, and DJs have shaped modern lindy hopping practices, have these practices in turn then shaped the way ‘dance bands’ created by and for modern dancers, put together live and recorded sets?

Hm. If this is the case in the States (and I’m not entirely convinced it is), are the European, Japanese, and other regional jazz bands working with dancers reflecting this pattern? Is it the case in Japan, where jazz flourishes, but contemporary lindy hop culture lags a little? And what of bands like the Hot Sugar Band in France, who play for dancers, know dancers, but have a kind of take-no-prisoners approach to live music (and hotel rooms)? Even within America, it’s not an entirely accurate observation about New Orleans, where bands are engaged so actively with a diverse local live music culture.

I know that here in Sydney we have a rich and vibrant live jazz scene, and because bands are playing their gigs, for mixed crowds, they play a range of styles and tempos, and different songs lengths. Even when booked for dancers, and working with dancers to develop ‘dancer-friendly’ sets, they are still holding onto these jazz traditions: playing latin rhythms, playing a range of tempos, and songs of all lengths.

For the most part, dancers are happy with these arrangements. We’ve learnt to enjoy figuring out what to do with something latin rhythmed, or how to handle a super long song. And the strategies we use are similar to the ones Peter outlines in his talk, the sort of strategies that OGs used in the swing and jazz eras.

Interestingly, Sydney is home to the oldest lindy hop scene in Australia, local dancers travel extensively overseas, and we have flourishing balboa, lindy hop, blues, and solo jazz cultures. We aren’t a small, isolated scene with inexperienced dancers. We’re a large, diverse scene with fairly particular musical tastes.

Though we are an older scene, and we do have some exceptional dancers, our overall standard of dancing is a bit patchy, and we don’t have a huge DJing culture. We have some very good DJs, but we don’t have the pervasive ‘hard core DJing culture’ of the States. The organisers and DJs our bands do work with are often firmly rooted in live jazz history, and have a solid understanding of how to work with bands to encourage good dancing and satisfy musicians’ creative drives. Having said that, there are some truly terrible events in Sydney, with awful DJs, and poorly developed visions and guidance for live music. No one wins when the organiser doesn’t have a clue about music, or doesn’t have a passion for 20s, 30s, or 40s jazz.

Many of the better, more experienced Sydney musicians publicly question dancers’ insistence on shorter songs and ‘moderate tempos’. They’re a little more obstreperous, risking gigs because they aren’t as prepared to compromise. Though of course, that’s changing, as recent funding cuts to the arts in Australia (50%!) have sent a significant proportion of our musicians overseas seeking work. If you’re in Paris or the UK, you can catch some of Melbourne’s finest, and if you’re in the Asia-Pacific region, you can often catch a Sydney band touring.

I’m actually very interested in the way local Sydney bands have begun working with dancers for mutual pleasure and creative satisfaction. The Squeezebox Trio have a long standing relationship with balboa dancers at a Wednesday night bar gig, Andrew Dickeson’s Blue Rhythm Band is pursuing Basie’s dance band legacy, working with people like me in Sydney, but also playing at all the major Australian events in 2016. Swing Rocket has played for dancers here in Sydney, but has also played a number of shows in Guadalupe with French musician Tricia Evy and Stockholm based lindy hoppers Marie N’diaye and Anders Sihlberg.

All these bands are staffed by musicians who then go on to work with other local bands, spreading their experience and inspiration from working with dancers. Musicians have been enthusiastically involved with projects like my Little Big Weekend event, where we built tap dancers, singing dancers, and musician-dancers into the program. In my events, I am determined for the music to be more than a ‘background beat’ for dancers. I want musicians engaged with dancers (and vice versa), and I want to use live music in a lot of different ways. For example, earlier this year we had Georgia Brooks arrange a sung ‘word from our sponsor’ to perform with the band during our competition. I’ve also had the band do a ‘practice competition’ with our students at a local gig, so they could all learn how to do a competition with live music. The last was especially fun as we were all trying new things,from seasoned musicians to beginner dancers and organisers. And we went into the enterprise with a spirit of curiosity and determination. And a love of jazz.

I’m not sure how to get to my original point (I did get up at 5.30 this morning), but I wonder if all this means that Gamble’s band and Doyle’s band are perhaps too perfect for dancing? Has the close association with dancers moved them away from a jazz tradition and towards a contemporary lindy hop tradition? But a lindy hop tradition that is a little too carefully curated for the ‘perfect dancing experience’? It’s a tricky issue.

Michael Gamble has been heavily involved with promoting historical swing arrangements and recordings, as well as recreating those with the musical program of events like Lindy Focus, so we know his work is rooted in the past. Which I suppose is my point: is a hardcore recreationist project at odds with the spirit of jazz? If vernacular jazz is about change and growth, innovation and improvisation, does it lose its impetus when we focus on recreating a specific moment in time?

It’s all quite interesting and challenging. And the issue puts us at odds with the function of a dance band (make people dance; make it easy for people to have fun). Can a modern jazz band support that goal while also pursuing musical creativity and innovation which might make for awkward dancing? Can a band honour the past, while also moving forward?

I think it can. But as I’ve ranted in other posts about rhythm-first approaches to dancing, we can’t approach a ‘good dance’ as a series of moves perfectly executed. A ‘good dance’ should have two rules: look after the music, look after your partner. A good dance to a live band should involve an interruption of the sequence of ‘perfect moves’ to pause and just jockey in place, digging the band. Or simpler shapes which allow partners to turn and smile and cheer at musician for an especially excellent solo. Or joke. Just as a good DJ needs to look up from their computer, a good musician look up from their score, a good dancer should look up from their partner and engage with the band, and everyone else in the room.

This is an extension of my question: is it possible for a band to be too perfect for dancing? I’ve lately become a little tired of Gordon Webster’s band for just this sort of reason. The songs he plays are predictable in structure and emotional progression, and just a bit too ‘easy’ or ‘perfect’ for dancing. You can hit every break. You can hear all your favourite songs.

Really, though, this is a silly question. These musicians are working on projects they find satisfying and challenging, interesting and fun. And it gets them work, which is the point of jazz, really, isn’t it? Being socially and creatively sustainable. Earning a living wage and playing music. And the nicest part of swinging jazz is that this playing of music is social. It asks artists to play for and with audiences, rather than locking themselves away in a garret creating ‘art’ that no one ever listens to or engages with. Swing jazz, as dance music, asks musicians to work with dancers, and it asks dancers to engage with music actively, as dancers. Whether they are up on the floor dancing, or turning their ears to the music, breathing it in as people who dance, or feel rhythm in their feet and heart.

That whole issue aside, what’s to be said about these two albums?

Bluntly, Gamble’s album is accessible, and makes for good foot-stomping dancing.

Doyle’s album is more cerebral, more of a toe-tapper than a foot stomper.

Other than that, they’re very similar. Small, swinging bands playing fun swing music.

If I was writing from my gut, I’d say that the Doyle band is a bit squarer than Gamble’s. Which is a feeling I had about their previous recordings. I enjoyed the Doyle, but it doesn’t quite let loose. There’s something in the brass, and wind instruments which says square to me. I’m not a musician, and sadly too slack to educate myself on this point, but it sounds like there’s a lot of very controlled synchronised work there. I feel like things are a bit too safe, a bit too carefully planned out. To me, this sounds like they’re used to playing for each other, more than for dancers. Or if I picture them in my mind, they’re sitting in a circle, facing each other, making it a bit harder for the audience to get in. or they’re reading sheet music, eyes down. This could of course be a matter of the mix or recording technology, with something in Gamble’s recordings lending a warmth or accessablity to the album.

They actually remind me a bit of a band I saw at Herrang, Kinda Dukish. Fantastic musicians, but as a Swedish sound engineer described them, ‘very German’. In other words, very precise. Very good.

My favourite song from this album is ‘Good News, Bad News’. Probably for the muted trombone. ‘You can’t Take These Kisses With Ya’ feels a bit sprightlier, and funner. There are parts of ‘Comfort Zone’ which are especially good. The album does open with a bit of a bang with ‘Sugar Glider’, but even this song is a bit too polite. Though I begin to feel like all the musicians are politely ‘taking turns’, rather than clumping in to give us those layers of sound and aural colour that makes for good dancing.

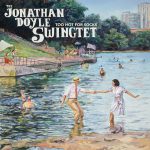

One of the nice parts of this album is that the cover art features dancers I know (via the internet), drawn by dancers: what a lovely combination. And an example of how ‘swing’ isn’t just about dancing, but a cultural nexus, with dancing just one point on a continuum of cultural practice. A little as Lee Ellen Friedland describes hip hop. I really enjoy this little example of how the band is bedded down into its local dance community.

Gamble’s album, in contrast, comes in like they’re playing for dancers. I know it’s a cliche, but dancers do like vocals, and it provides a point of connection. It’s a bit of an overplayed favourite, but ‘I Left My Baby’ is a good opening song. It provides a point of familiar contact for newer dancers, and it makes experienced ears ask, “Ok, what’re you going to do with this old chestnut to keep my interest?”

‘Disorder at the Border’ comes in the way I like it, with a definitely Basie feel in the rhythm section. I think it has something to do with the sense of relative timing in that rhythm section. Where Doyle’s band feels very neat and in unison almost, here, the Gamble band has the guitar, piano, bass, and drums sitting in slightly different places.

You know what, I don’t know what I’m talking about. I can’t find the words to explain what I’m hearing.

One of the clever parts of this album, is the way it moves from that Basie-esque feel to a smaller, more uptight Goodman small group feel with ‘Airmail Special’, and then on to say hello to Andy Kirk with A Mellow Bit Of Rhythm. I love the version of ‘Seven Come Eleven’, one of my most favourite songs. I really dig that ‘Slidin’ and Glidin’’; I’ve DJed it a few times, and it goes down a treat.

I have to make special mention of Laura Windley’s vocals. I’ve enjoyed her work with her own band, the Mint Julep Jazz Band, and I’ve heard she’s grand live. But I really liked her version of ‘Fine and Mellow’ on this album. It’s hard to sing a song like this, which is so indelibly stamped by Mz Holiday’s voice. When you read the title, you think of that incredible live recording, and Lester Young and Holiday passing the feels back and forth. So to come to this song and give it new feels is a real challenge.

But I think this is my favourite song on the album. The one I’ve listened to quite a few times. Laura changes the vibe, gives it something interesting, and a little more energy, but keeps the clarity and brightness Laura’s band and style are known for.

Yes, it’s all really good dance music. It makes for great dancing. I saw John Tigert drop songs from it at Herrang, and people loved it. But that’s part of my issue with this album. I feel like I’m listening to a good DJ set. The songs are picked from different bands, with different feels, and it’s all great. But I don’t quite feel like the band is taking any risks. I know I’d almost certainly have a good time dancing to this band live. I’d enjoy the performances. I’d hear favourites, plus a few of the ‘currently cool’ ‘newer finds’. But I’d be left wondering exactly what the _point_ of it is. Yes, I do like eating potato chips (a lot). But occasionally I like something a little more challenging to the palate.

In sum, then, this is a very good album. Buy it if you want some easy ‘DJing wins’. Buy it if you want something simple and easy to eat/dance to. As I did, buy it if you want to support bands who play fun music for dancers. But it doesn’t take any risks.

Too Hot For Socks – 2016 – Jonathan Doyle Swingtet

and

Michael Gamble and the Rhythm Serenaders – Michael Gamble and the Rhythm Serenaders – 2016