I believe that our dance community is generally well behaved, and I am not sure we need a codified response. Just be respectful to everyone, respect their space, dont abuse your position, much the same as in everyday life. Dancing gives no extra rights to misbehave. But we are all adults, right?

I get people like the thought of a code of conduct because it makes people feel better but all i see is another paper in a system that should be a far more simple system of either make that person leave, call the police that’s against the law common sense.

I feel that as a bunch of adults we as a community should not need a code of conduct to dictate that we obey the law.

These are a few quotes from recent online discussions about sexual harassment policies. They are taken out of context. My aim here is to show the language that’s used to defend these positions. These are actual examples of quite common phrases used in these discussions.

The number of people publicly saying ‘we don’t need codes of conduct’ or sexual harassment policies in lindy hop is increasing, the further we get in time from the stories about Stephen Mitchell. I’m not entirely sure what their motivations are. But we can read these statements as suggesting, ‘I don’t think rape and attacks are important enough to change the status quo.’ I wonder if their opinions would be the same if people were being knifed or bashed or kicked. I don’t think they realise that rape involves physical pain and violence, as well as intimidation and threats. Sexual harassment or grooming of girls and women by predators involves systematic intimidation, threats, isolation, and manipulation over a long period of time. Or perhaps they simply don’t think violent attacks on women are important.

There have been a number of high profile rape and assault cases in the international lindy hop scene over the years, and sexual harassment is an ongoing issue. The consequences (besides horrible stuff happening to our friends) include drops in class numbers and event attendees (ie financial consequences), and a loss of community knowledge (ie social sustainability declines as people with experience leave). And yet many dancers are still reluctant to take clear, positive action to improve the safety of their friends and peers.

We need to be more proactive in preventing and responding to this issue, because men in our dance community don’t seem to grasp the fact that raping women and girls is not ok. Offenders know that their actions are illegal, immoral, and disrespectful. Offenders also know that no one will call them on their behaviour. They do these things with no real-world consequences. They know that other men will not challenge their behaviour. They know that women feel alone and vulnerable.

Me, I’m done with that bullshit. Reading all those accounts of girls and women assaulted by Steven Mitchell and other men, I was galvanised. I am an organiser. But I am also a human being, who cares about her friends. I simply can’t look away or pretend this isn’t happening. Does this make me braver than the men who don’t speak up? Probably. But I can’t do this on my own. Codes of conduct are about collective responses: we work together to look after each other.

My focus now is on the way men don’t call other men on their behaviour. Calling out offenders is left to organisers, and to women. As the comments I’ve quoted above suggest, there is an assumption that sexual harassment is a problem for organisers and women, and no one else. Me, I think it’s a problem we should all be looking at. Most particularly men, because it is men who commit most of these offences. Interestingly it is when I call out men for not stepping up that people get angriest with me. Because, I think, this is the matter that most destabilises the status quo. Or as we femmostroppos like to say, this is the point at which we address patriarchy in the most explicit way.

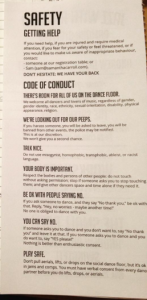

Why are codes of conduct important?

You may choose to have a ‘statement of intent’ or a ‘manifesto’ or a set of ‘rules’. This document or blob of words is not implied or hinted at or common sense. It is a clear and explicit statement of your values, and your limits.

Codes of conduct are important because they:

a) Are a public symbol telling people that your organisation is not ok with sexual assault and will act on reports;

b) Make explicit implicit or implied ‘common sense’ standards and rules. So that we can actually be sure we all have ‘common’ (or shared) values and ‘rules’.

c) This then gives teachers/employees/contractors within the organisation a set of clear guidelines: what are our ‘goals’? What is our position on this? This then guides future policies and actions;

d) It gives students and punters a clear outline of what the organisation’s policy is;

e) Give you an ideological guide for developing policy;

f) Give you a clear list of ‘rules’ to set in your agreements with contractors like musicians, DJs, and teachers. Basically, I say “by working for me, you agree to read and abide by this code. If you can’t agree with it, then you do not work with me or attend my event.”

b is especially important, because the vague or implied ‘common sense’ rules (instead of explicit rules) are used by offenders as an excuse – eg “I didn’t know it wasn’t ok.” It’s also increasingly clear that some men and women simply don’t know what constitutes sexual harassment. So women don’t know that they can trust their instincts, and men don’t know that what they’re doing is sexual harassment.

My code of conducts make it very clear: if you can’t agree to not rape people, you are not welcome at my dance or in my community.

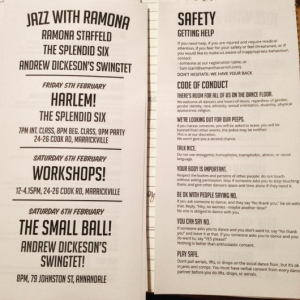

Since our organisation Swing Dance Sydney instituted a code of conduct and clear oh&s policies, dancers who identify as queer or trans, young women, decent men, have said that they feel welcome at our events, or at the least the idea of our events makes them feel welcome. Basically, we are making our events openly hostile and uncomfortable for male sexual offenders, and much friendlier and more welcoming for everyone else.

Our events are also much better as a result of all this work. We’ve just put on better events because we’ve had to think through how we look after people, how we develop and design guidelines and practices, and then we implement and communicate them to workers. This means that there are fewer fuck ups in the program, fewer technical errors, and less general bullshit. Because we’ve gone over these bloody things so many times we’ve caught most of the common problems and fixed most of the crap.

I don’t think codes are enough on their own, but they are important. I have adopted them for all my events, in both paper and digital forms.

But I have also developed:

1) Practical strategies for responding to complaints (eg banning offenders, then training staff to respond when those banned offenders turn up at events).

2) In-class teaching strategies to effect cultural change (ie making it clear that sexual harassment is not ok; skilling and powering up women to give them confidence; teaching men how to touch women with respect).

3) In-person strategies for talking about our code (eg I do speeches at our events that are both funny and important).

4) Skills for dealing with offenders myself.

5) Policies and training that skill up our volunteers and staff so they can step up.

I have already has SERIOUS and marked responses to these policies. I have banned serial offenders. I have responded to women’s complaints/requests for help. I have skilled myself up in confronting frightening, aggressive men. I have dealt with musicians, DJs, and dancers who sexually harass.

Our classes are much better, and we’ve seen students developing good lindy hop, the confidence to improvise (and not micromanage their partners), and we see great social dancing.

I have learnt how to address and teach follows in ways that actually articulate what following is. None of this ‘just follow’ crap for me. This has helped me and my students see how follows (and implicitly, women) are not just objects to be moved about by leads.

Our door staff are more confident and capable. Our musicians are more engaged with us as people (not just punters). And the parties are heaps more fun.

Our events are better. I think that this is the most important part: by taking greater care with one particular issue, and for one particular group, all our punters are better taken care of. Our events and projects are simply better, because we have had to think through these issues and implement strategies. It’s pushed us to become better at what we do; we don’t just continue to do things as they’ve always been done. I actually think this last point is the marker of working with an ambitious, motivated group of people. And they put this sort of energy and focus into their dancing too, which makes the dancing so much better as well.

Relatedly, the ‘common sense’, or ‘we’re all just decent people’ discourses that inform labour relationships (DJing, teaching, volunteering) within the lindy hop world often facilitate exploitation. The implicit hierarchies of power enable exploitation (and sexual harassment), but do not necessitate the reciprocal duty of care and responsibility that goes with formal declarations in other hierarchical social systems.

Basically, the ‘we’re all decent people’ and ‘common sense’ approaches haven’t stopped sexual assault and harassment in lindy hop. They’ve enabled it. So either we change it to help people, or we let things stay the same and accept that we are enabling rape.