I used to be a huge proponent (zealot?) of ‘bouncing’ in lindy hop. I was sure it had to always be present while lindy hopping. The word ‘pulse’ has largely replaced ‘bounce’ in the vernacular, in part through the influence of American blues dance and west coast swing. It’s a great concept, and ‘pulse’ is useful because it implies an engagement of the core (the guts, etc) before/to initiate movement. More to the point, swinging jazz music has a very clear pulse or bounce, so it’s a good place to start in making friends with the music.

In the past year, I’ve changed my position. I was very resistant in a class with Toddy Yannacone a few years ago (2008? 2009?) when he suggested that we might sometimes not pulse. That sometimes we could be flat. To my Swede-drenched mind, this was totally not ok. But I had had increasing problems with calf muscle tears and strain, and simply working too hard.

Then I did a class with Kieran Yee at some point a few years later (2012?), where he talked about pulse at higher tempos. He basically made the point that you don’t have time to do a really deep pulse, so it has to be shallower, and faster. He explained this as the bounce sitting higher in his body (ie at the middle of his rib cage, rather than down in his hips). Once I heard and saw this, I realised that I had a ‘default bounce’ that was quite deep. Fine for slow songs with a deep pocket/super swing. Not so good for hotter, faster music.

[a note on gender: a lot of peeps talk about women as having a ‘lower centre’ than men, and women leads as leading from this lower point. I feel that this isn’t strictly accurate. As a decent dancer, and as a woman, I have to learn to engage and ‘lead’ from different points in my body, not just one static ‘centre’ down there over my womb. Because active muscle engagement, yo, and my womb is actually a rubbish lead. The very point of this discussion is that we can choose where to initiate movement, not just default to one option]

Listening to a lot of very early jazz and pre-swing, I realised that the ‘bounce’ in this music is jumping about much higher in the body, rather than planting four solid feet on the floor. So I needed to adjust my sense of time to account for this. To be clear: this ‘bounce’ is not necessarily a ‘jumping up’ bounce. It can still bounce ‘down’. But the depth of this bounce, and being able to choose whether I was bouncing up or down was very, very important. It meant a rethinking and examination of the fundamentals of my movement in lindy hop. It was really brought home to me in my first tap classes with Daniel Larsson, where he made it clear that a very swinging, broad ‘bounce’ to keep time was going to make a lot of tap movements very difficult. I had to get more efficient and more controlled in how I used my body to keep time.

Let me show you some videos.

In this one, Sakarias and Isabella are dancing to a faster, hotter jazz song with a very shallow pocket. Watch Saki’s body. He’s holding himself higher in his body (though he’s still very ‘grounded’). No, that’s not his dick, it’s the zip in his trousers sitting at an odd angle. So stop looking at that. Look at the way his arms remain loose and relaxed (yet engaged), he has lovely rhythm emanating from his core, and his feet take smaller steps (except at a couple of points for emphasis). His kicks are a product of his body on his standing leg contracting or bouncing a little in place, not a KICK from the leg.

Now, look at this other video of Saki. Yes, I do like his dancing. What of it?

He doesn’t sink down into the ground as a blues dancer would, but he’s definitely moving in a very different way, with a deeper swing to his timing, and a different relationship to the ground.

[As an aside, note at 1.08 how Mimmi uses Saki’s body to move around him with greater energy and space than he has suggested. They are working together to make this work, as he engages to keep balance and help her through this crazy movement, but she is definitely not ‘just following’ or ‘making a variation’. She is fundamentally changing the energy, size, timing, and feel of this one shape (a swing out). And it feels good with the music.]

In these two videos, you can see how one dancer adjusts his ‘groove’ to suit different music and different partners, in a crowded or a more empty dance floor. Yes one is a performance (and so a bit more exaggerated), but the fundamentals of his movement are consistent: he makes choices about how to groove with the music, in ways that reflect the feel of the music. It’s no surprise that Saki is a tap dancer and drummer, right?

What I’m doing now.

Now, though, with my renewed focus on music-first teaching, and my own deepening understanding of jazz and of rhythm (through tap), I understand that an ‘always bouncing’ lindy hop isn’t really listening to the music. More importantly, a single type of ‘bounce’ is severely limiting. Our teaching group realised that insisting on a consistent uppy downy ‘bounce’ gave us little robot dancers with identical uppy downy movement. Regardless of the music.

So we copied our street dancer (hip hop, house etc) friends and started calling it ‘groove’. Now we see beautiful dancing and a much better connection to the music in our students, and I feel a lot better in myself as a dancer.

…as I type this, I feel ridiculous. But having ‘bounce’ was very important to me in a city where no one had any type of bounce or groove in the early 2000s. So moving on with my own development as a dancer was thwarted by my own determination to hang onto this one particular understanding of keeping time.

Well, we all have little jumps and leaps to make in our learning, right? :D

Hanging out with more street dancers (ie people who dance house, hip hop, locking, vogue, etc etc), I’ve learnt a lot more about ‘keeping time’ with my body. It’s been important for me to be teaching with friends who do regular street dance classes, including Jess‘s very good ‘grooves class.’ In her teaching bio Jess writes:

A baby must learn to stand, in order to walk and in order to run. Same sort of concept where I will show you the basics of getting to know the music, in order to dance with the music, and then style your dancing with the music. Hip Hop has its history and I will share its story with you. Relax, Have Fun and Be a better you.

These guys are also really connected to the roots of their dances, and do work with hip hop OGs. At a class with one man in particular, he demonstrated keeping one groove in your body, then adding another. Or moving it around inside your body.

We have taken this idea and started experimenting with it on our own. Taking part in classes with drummers and dancers from Guinea (Ousmane Camara) and Mozambique (Carlos Machava) this year in Herrang (back to back with my tap classes with Josette Wiggan and Daniel Larsson), I understood that the very nature of polyrhythms means that you can hold a number of ‘grooves’ in your body. Where previously I’d understood this concept as meaning you lay down your basic ‘bounce’ and then just layer rhythms on top of it, now I think of it more that your body contains a whole range of grooves, and the more control and the better ear you have, the more you can experiment with this. As a wee babby, I’m still working on one or two grooves at a time :D

The wonderful thing about beginning with African dance (as lindy hop did), is that you realise that you do all this on your own and then you DANCE WITH SOMEONE ELSE DOING THE SAME!!! So a partnership allows you to carry more rhythms and beats with you! Of course, a non-touching dance in a circle allows far more partnerships and layers of rhythm, but I guess that’s why african dance pwns all, right?

Defining groove for teaching purposes

To simplify things for teaching, I think you can think about a groove as ‘the basic rhythm of this song as you hear it.’ So we can have different grooves depending on who we are. This can include a nice bouncy pulse. Or it can be a flattened slide. But just as in tap, you have to keep the time internally, no matter what you’re doing, and to be really listening to the music, you have to be able to show this time in different ways. Not just one regimented uppy-downy pulse.

Importantly, the fewer words you use to describe or explain something in class, the greater the scope of your students’ imagining of that concept. You don’t need to explain ‘music’ to a human; they can hear it. If you can see (after ages) that they don’t have the beat, you can demonstrate with your body where that beat is. You don’t have to explain it. I think that a lot of modern lindy hop teachers in the western world like to capture and pin down the meaning of a concept. Stop it from changing or being ‘misunderstood’. If you talk less in class, and have students learn about movement and music through trying it first (rather than answering their questions with words, or giving long explanations), you let them experience that concept first. They don’t really need to understand it with their brains. I mean, look at the concept of ‘swing’. We have a million ways to describe what it is and how it works, but at the end of the day, to misquote Armstrong, “Man, if you have to ask what jazz is, you’ll never know.”

Remind me to write up my new ideas about questions in class, will you?

I recommend ditching ‘pulse’ as a buzzword, and going with groove. Or something else that suits your language and vibe. Or just a demonstration. You get the same effect (activated cores, engaged muscles, good prep for movement), but they’re dancing not jerking up and down.

As a teaching tool, the concept of ‘groove’ is very nice, because you’re never telling students they’re doing it wrong (by saying ‘bounce down, not up!’ or ‘deeper!’ or whatevs). You’re just saying “Find the groove,” or “Make friends with music,” or “Put the beat in your body and hold it there,” and they just do it in their own way. I have found it really inspiring, because I see a room full of people really dancing on their own, even before they do any ‘moves’ or ‘steps’ or figures. And they feel really good. Once they get over feeling shy or silly :D

I also say to students “Can you keep the time for me while I demonstrate this, please?” And get very good results. You don’t have to say how they do this, just ask them to show you with their bodies. Or, really just saying “Can you keep the time for me, please?” is really enough. People get it. Especially if you’ve been teaching by showing all class. You just can’t get this wrong.

They feel that responsibility to keep the time for the people demonstrating, and as a circle of people effectively watching and participating in a jam, they feel that shared sense of time that makes a tap jam or cypher or battle or drum circle so exciting and fulfilling. It also makes it clear that they are responsible for keeping their own time, and that this isn’t a ‘basic’ thing, but a fundamental part of dancing. Something we trust new dancers with right from the very first moment. We don’t need to drill them on it or micromanage it.

And if we free ourselves up from this very regimented idea of ‘bounce’ or ‘pulse’, we allow ourselves and our students to grow and develop as dancers and as musicians.

From a biomechanics point of view, the ‘groove’ approach allows dancers to shift their weight around from foot to foot, from the front to the back of their feet, to move their arms, their hips, their bodies however they like. A sort of ‘testing’ of balance and engagement which is relaxed, cushioned, and fluid. In this process we can experiment with turning on and off muscles, with seeing how the angle of our bodies affects our balance and ability to move.

This makes a great deal of sense for follows who are already used to the idea that they have to be ‘ready for anything’ a lead my suggest. But it’s also very good for leaders, who are forced (encouraged?) to stop thinking about leading as a ‘I ask, you do’ relationship with a follow. The range of movement encouraged by a groove (vs a pulse) allows the lead to experiment with the effect of their own weight change, and the way it frees up their body to feel and respond to a follow’s movements. And of course, it’s just more interesting and fun. Standing on the spot in closed position, grooving, suddenly feels really satisfying and wonderful – like DANCING – instead of just waiting for the dancing to begin.

Sore Knees and ‘technique’.

Another consequence of a pulse-focussed approach to keeping time is that you often see a lot of sore knees.

I have had a lot of trouble with knees in the past (because lindy hopper who didn’t do any pre-dance training), and had to get my shit together with squat technique.

Why do the knees get so sore? Now, I’m NOT a medical professional! But my physio made it clear that my issues were:

- too much repetitive movement with poor technique

- too deep a downward push

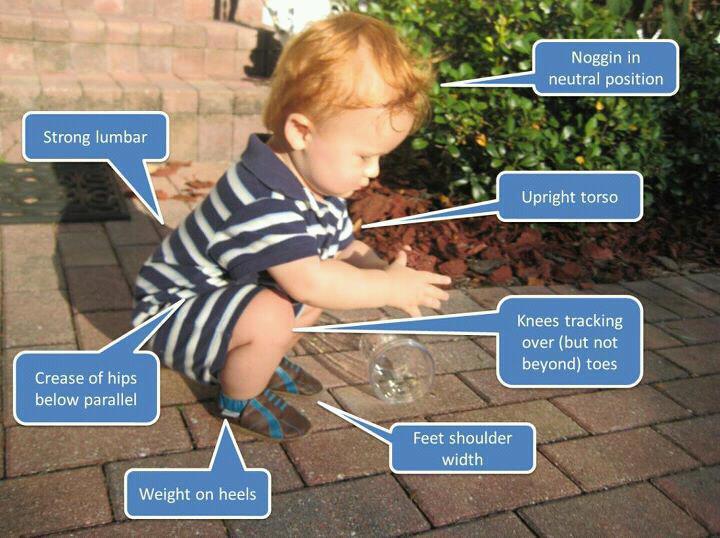

- knees too far forward over toes. Knees should not go further forward than toes. So the butt needs to go back to achieve the depth. ie literally the good squatting technique you learn in pilates.

We don’t tend to squat as deep as this wee kiddy in lindy hop, but the techniques apply.

I actually don’t think a dance class is the place to work on this technical stuff; as people (mis)quote Frankie Manning: “Don’t do lindy hop to get in shape, get in shape to do lindy hop.”

Anyhoo, this is why ‘out with the butts’ is not just a problematic exoticising of the african american body, but good biomechanics. Similarly, ‘look at your partner’ keeps the upper body open across the chest, and the chin up.

Where does this sit in regards to my developing sense of lindy hop ‘pedagogy’?

Firstly: my goal has always been to help students become individuals. To express themselves. If I end up with a bunch of people who move and dance exactly like each other, and like me, then I have failed in my job.

I had thought this was a common goal in lindy hop teaching. But my recent experiences have led to me believe that this is definitely not the case. A lot of high profile international teachers are determined to create uniformity. I’m sure this isn’t their explicit goal. But it is a consequence of teaching to ‘get rid of bad habits’ or to ‘fix people’ or to ‘stop people doing X.’

It’s a hard thing to accept, but as a dancer and teacher, I have to accept that we are all different human beings, and even though that lack of triple steps in a lead’s swing out ENRAGES me, that is their choice. And not mine. I have no right, NO RIGHT to try to ‘fix’ that.

The Frankie Track in Herrang in 2014 really brought home to me, with the multi-level class, and focus on rhythm not shapes, that if we focus on rhythm not the perfect execution of figures, we open our brains up. Suddenly everyone is potentially a fantastic dance partner, and they don’t need eleventy years of experience and perfect ‘technique’ to be a wonderful dancer. It was very exciting for me as a dancer, and I think it really made me a better person to approach dance this way. I really did get over myself.

Secondly, I have (as I’m sure I’ve made clear in my previous posts about jazz dance skills and followers’ skills), been working on revising how I approach teaching lindy hop. As Anders put it in class the other week in Herrang, we can teach our students using a road map to get to a specific destination, or we can go with them on an exploration. That road map is essentially a specific ideology about dance and about teaching. Whether it is ‘rhythm first!’, ‘learn-by-drilling’, teacher-centred, student-centred, or purely through experimentation. As Anders made clear, as teachers we have a whole range of teaching skills and tools available to us, and we want to be active in our selections from these options. So sometimes we might drill people, but other times we might encourage them to come to a movement through experimenting.

I do find this very exciting. And I like that it gives me permission to use a very conventional class structure sometimes, as well as lovely hippy dippy gentle teaching tools. As a teacher, and as a student, I like that this philosophy encourages me to ask questions, and to engage with the ideas and practice actively. Not necessarily actually verbally ask questions, but to approach a new move or concept with an inquiring mind, to try and take it apart and see how it works. Not just accept the concept as given.

And this is, of course, very much in keeping with many of the approaches advocated by the earlier cultural studies and women studies scholars. So I find this approach to teaching and learning very much in keeping with my broader feminist projects: do good in the world.