Someone posted a photo of a man ‘manspreading’ on the tram to facebook, and there was a good discussion about it. For me, manspreading is a physical version of mansplaining, or of patriarchy. A (male) friend made this comment about the original post:

I sit like that..but i would 100% sit less comfortably so that i dont put others out like that. I find both men and women go about thier day unmaliciously unaware about how inconsiderate they are towards other people across a range of general day to day activities. I think if everyone made an effort to be empathetic in general things like this wouldnt happen..

This is a very sensible and reasonable response. It’s what I tend to think of as a humanist or individualist response to a feminist critique. On one level, I’m in agreement. But on another, I don’t think this approach actually captures the nuance of human relationships. Feminism begins with the assumption that men and women experience the social world in different ways. And these experiences are shaped by social forces and institutions which favour men.

I like to add detail to this, by adding the notion of ‘patriarchy’. Patriarchy is an organising force or ideology that organises institutions (schools, business, markets, hospitals), discourses (discussion, media, the exchange of ideas, things), and lived reality (our physical experiences). One of the key features of patriarchy is that people are organised not just by hierarchies of gender (where men have more power than women). They’re also organised by class (rich men have more power than poor men), by race (white men have more power than men of colour), by sexuality (straight men have more power than queer men), by age (middle aged men have more power than teenaged men) and so on. The ‘most powerful’ man, then, is rich, white, straight, and middle aged. We describe this type of ‘most powerful’ man as hegemonic masculinity.

It’s important to note the difference between ‘man’ and ‘masculinity’. ‘Man’ is about biological sex. Masculinity is a social construct. That means masculinity is a product of the way boys are taught and learn to act as men through formal institutions like schools, churches, and armies, and informal relations like families and peer groups.

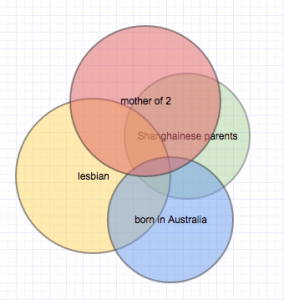

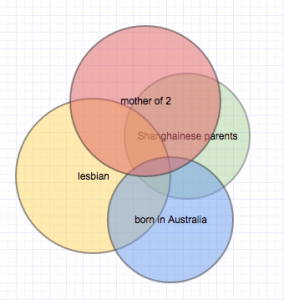

Most recent feminist talk has approached this issue in terms of ‘intersectionality’. In the late 80s the more common term was ‘diversity politics’ or even postmodern feminism. But that thinking has been refined and developed to become intersectionality. The word gives us the image of a number of sphere or lines ‘intersecting’ at a particular point. Here’s an example. Let’s imagine a woman called May who has Shanghainese parents, is a lesbian, was born in Australia, and is the mother of two children.

All of these things make her the person she is. Let’s also imagine May identifies as a Chinese-Australian lesbian mum. This identity is the intersection of the traits that May considers most relevant (to this conversation at this time).

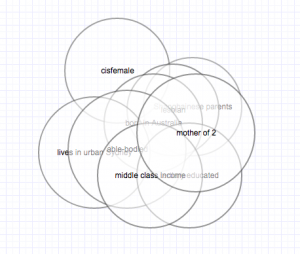

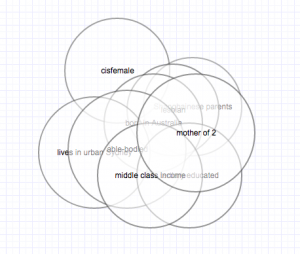

Of course, May’s person is the intersection of many more characteristics.

She’s also tertiary educated, cisfemale, middle class, lives in urban Sydney, and is able-bodied. At any time she may identify as one or a combination of these characteristics. This is important: choosing how to identify, is a mark of social power.

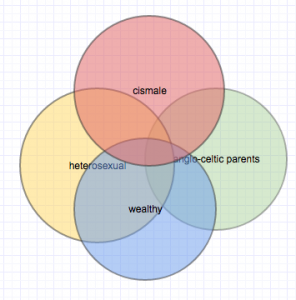

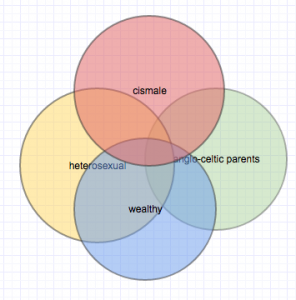

If we return to our hegemonic masculinity, we can see that this identity also exists at the intersection of a number of characteristics:

The important point here, is that the power of this hegemonic masculinity lies in not recognising the different elements that contribute to this status. A man like this, occupying a position of power and influence, a businessman for example, might describe himself as a ‘hardworking, self-made man.’ He may attribute his position of power to working hard all his life. Which may be true. But his gender, class, ethnicity, and sexual identity mean that he is allowed to marry the person he wants, has access to better housing and health care, and has not faced racial discrimination.

Not acknowledging these advantages is an important part of patriarchy. The myth that power and success comes from hard work (rather than privilege) is an important part of capitalism as well.

So let’s go back to manspreading.

How is this an example of patriarchy at work?

I replied to that comment above with this

It’s partly about how men and women feel about occupying public space. Women are trained to take up as little space as possible – to be smaller, to talk softer, to be less confident, to avoid conflict by becoming invisible. Whereas men are trained to sit wider, stand wider, talk louder, disagree, to ‘stake their claim’ on space and ideas, to ward off conflict with a show of strength, take up more physical and audible space.

If a woman does break these rules – is louder, bigger, more confident, more visible – we have lots of ways to shut her down. Slut shaming, comments about being ‘strident’ or ‘shrill’, etc etc.

So manspreading enrages women because it’s about men being so comfortable with occupying space they don’t even to stop to consider their behaviour.

NB this is culturally specific.

When I talk about ‘public space’, I’m placing it in opposition to ‘private space’. Public space includes inside public transport like a tram, on the street, in shops (though these are technically private spaces, they function as publics), in the media, online, in parks, and so on. Private space includes the home, family, inside a car, personal email.

When I say ‘men and women’, I am talking about the men and women of urban Australia, a post-colonial, space in the modern, white-dominated developed world. The photo of a white man manspreading was taken on a Melbourne tram, where he is occupying more than half a seat he shares with a white woman:

Using textual analysis and an understanding of discursive context, we can identify them both as white, probably white-collar workers in urban Australia. We could make some guesses about age, and we could probably extrapolate about sexual preference. But the most important features here are gender and posture. He occupies more space with his wide legs, his relaxed, open shoulders, his joined hands, extended elbows, forward-facing posture, raised chin. She takes up less space with her closed legs, drawn-in elbows, compressed pecs, biceps and shoulders, her bag across her shoulder and in her lap. And so on. She also ‘closes’ herself to him by turning away and speaking on the phone. His ‘open’ posture suggests confidence and almost challenge (considering the context).

This sort of posture is not something that you see on peak hour trains in Seoul. Because Seoul commuters (the same class and age as these two) are taught culturally and socially to share space in a more communitarian way. There are certainly hierarchies of age and gender in the Seoul underground, but they operate in different ways.

Why is this the case?

If we follow the individualist reading, we could argue that the man has ‘won’ more space by being more confident, and by simply ‘stepping up’. But there is extensive research and observation proving otherwise.

Women in our culture are trained to think of public space as ‘dangerous’. They’re taught to be wary of rapists and physical assault, to preserve their ‘modesty’ and avoid unwelcome sexual attention by covering skin and literally keeping their legs together. They’re taught to avoid interaction and conflict by not ‘challenging’ others by using more than their ‘fare share’ of public space on a seat or in a tram. This includes speaking softly, not making eye contact, keeping their body ‘contained’ and ‘covered’, not speaking to or challenging men, not expressing their opinions, not laughing loudly, not swearing, not moving in a free way.

Women who don’t follow these ‘rules’ are disciplined with a range of strategies: men may ogle them, comment on their appearance, touch them, or interact with them despite being told to stop. These women are seen as having forfeited their ‘right to autonomy’ by being in public in particular way. Other women may be less overt, more effectively censorious: they may sneer at a woman’s body (she’s too fat!), eye her clothing (it’s too revealing!), mutter about her (she’s too loud!), draw away to avoid touching her (she’s contagious!)

The most important thing that I can say about this process, is that it is impossible for a woman to every behave or dress or be in a way that keeps her ‘safe’ from male attention and female policing. Because, despite the insistent slutshaming mythology of our culture, she is not responsible for men’s behaviour. Men are responsible for the way they disrespect women, though they are rarely held accountable. This is a very important point, because it makes women complicit in their own oppression. It makes women feel guilty for and accountable for men’s behaviour. It treats men’s behaviour as ‘natural’ and ‘inevitable’.

Even more importantly: if women are busy feeling guilty and vulnerable and taking responsibility for men’s behaviour, it stops them being confident and capable and asserting themselves. And this is how patriarchy polices women: we are convinced that we don’t deserve equal space on the seat, equal time in the conversation, safety in our homes, safety in public spaces.

Of course, power and privilege are largely invisible to those who have it. That white man on the tram probably has no idea he’s pushing that woman off the seat, or that the observing photographer is judging him. He might move over if you ask him to. Or he may be just as likely to huff and make a fuss about being inconvenienced by having to share. Because ‘when you’re accustomed to privilege, equality feels Like oppression‘.

Women, though, are far more likely to be aware of this inequity. Women are hyper-vigilant about their safety and bodies in public space. They sit in a particular part of the tram in a particular way to avoid conflict (note that woman’s almost apologetic use of the seat, her attention diverted by her phone to avoid a challenge). They avoid eye contact with strangers. They won’t tell an intrusive man to fuck off if he hassles her. Women wear coats over a skimpy dress in public, they don’t laugh loudly, they don’t ask these manspreaders to move over and share the seat. Because that manspreader is likely to see this request for equity as an injustice or challenge.

And here, of course, is the clincher. Women are trained to see themselves as vulnerable. Women are trained not to confront men about seat sharing, because they are afraid that man will hit them, shout at them, or humiliate them. Or – not impossibly – wait for them when they get off the train, then punish them verbally or physically. Women are taught to carry their bodies as though they were weak and vulnerable. To not ‘challenge’ male dominance with open, strong posture or direct eye contact.

This is where mansplaining comes in.

This dominance of physical space extends to verbal or intellectual space. Men are taught that their ideas are more valid, more important, more urgent than anyone else’s. More importantly, they are taught not to notice this, and to see this as normal. So when they do have to ‘share the floor’, they perceive an equal distribution of speaking time as inequity. And they respond to this as a challenge to their…status? Virility? Power? Who knows.

There’s a vast body of literature (primarily in linguistics and spoken discourse analysis – an area I did some work in during my MA work, and later employed in my analysis of online talk in my Phd) studying exactly how men and women talk in same-sex and mixed-sex groups in different settings. This somewhat dodgy post gives some interesting links (do make sure you read to the end.) Men and women use language in different ways, and they talk in different ways. I think it’s absolutely fascinating.

I have extended this model to my analyses of dance. Because I approach social dance as a public discourse: a place for the exchange of ideas and discussion and articular of identity. Through dance. So I see manspreading and mansplaining as two examples of male dominance of public space/discourse. Verbal/audio space and physical/visible space.

How does this relate to dance specifically? Well, we can look at the way some leads perceive the idea of ‘sharing improvisation time’. They may feel they are giving the follow equal time, but they do not see the power dynamic at work. Firstly, they do not understand that ‘giving a follow space’ is an articulation of the idea that the lead is the ‘boss’, rationing out ‘space’. This policing of improvisational space actually ensures that the lead is always in control of the whole dance. And of the follow’s body and creative voice. Secondly, their notion of ‘sharing fairly’ is skewed; it is not an equal division of time and space at all. In this situation I’d argue that this whole paradigm is poop.

This is partly why I really dislike the ‘dance is a conversation’ analogy. Because the type of conversation many men imagine they are having with their partner has more in common with mansplaining and manspreading: there is formal turn taking, but men interrupt more, take more time, and are more defensive and more aggressive, discouraging women from doing or ‘saying’ anything that could potentially embarrass or challenge a male partner. Deborah Tannen (linked to in the post linked above) points out that women and men use interruption in a different way. Women are more about collaborative meaning making (interrupting to exclaim “Oh my god, no way!” vs interrupting to mansplain and paraphrase a woman).

I would like to remind you that we need to think about intersectionally, here. While I’m saying ‘men’ and ‘women’, I should be saying hegemonic masculinity and talking about whiteness and class. The lead-follow relationships in modern Australian and American lindy hop are marked by class and race and gender and power. Much as people may like to pretend they are recreating the Savoy, they are in fact continuing the thinking and behaviour and relationships of their wider lives in the current moment.

As an example, listen to Frankie Manning’s discussion of leading and following as challenge in this video. He makes it clear that he enjoys being challenged by female partners. He also relies on women partners to help him get through improvisation. And he listens to his women partners’ improvisation and timing. It’s not exactly feminist talk, but Manning is articulating (and embodying) a masculinity that is an intersection of other identity markers: heterosexual working class masculinity of early 20th century urban Harlem New York jazz dance culture.

I’d like to add an addendum here:

In my experience, women who speak up about injustice – who question men’s behaviour or ask for equity – are attacked. Verbally. Physically. Legally. Financially.

I very rarely attack specific men personally for their behaviour, and if and when I do, it is always with bountiful evidence and with the express purpose of protecting women from his actions. Yet I am continually bombarded with emails, facebook messages, blog comments, letters, shouting down and interruption in public. I’m not particularly rude and I’m not aggressive. But I am perceived as such, because I’m not actually sitting down and being quiet.

It can be scary, but now that it’s happened so many times, it’s not scary any more. It’s just irritating. And I’ve also discovered that women are just much better at this public talk and action than men. Bitches get shit done.