Grey recently asked on fb ‘Ok, Feelings on bell hooks?’

And I got caught up in my response.

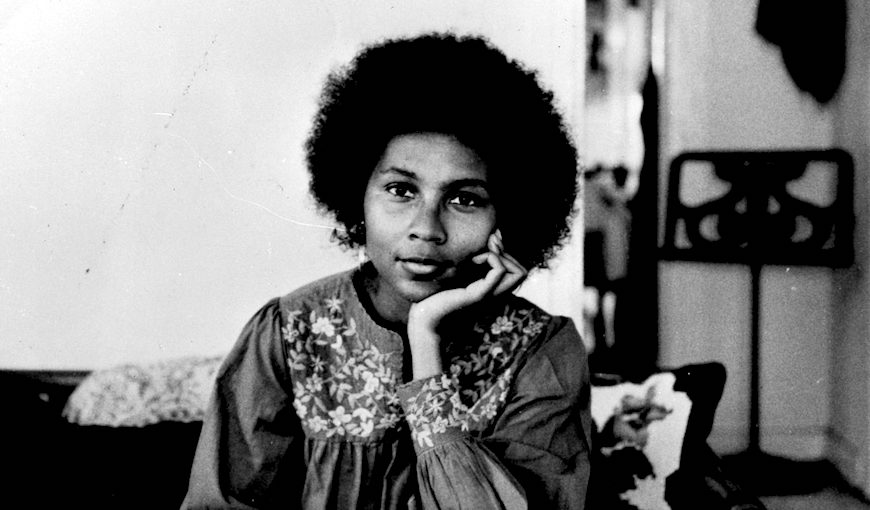

bell hooks was really important for me as a young feminist in the early 90s. At that stage, most of published women’s studies literature was by white women, and the women of colour who were getting published (primarily in journals, then in books), really shook up my thinking about class and identity. At the time, it really made me understand the intersection of class, race, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, etc, though at the time it wasn’t called ‘intersectionality’. I was a young, white woman in a working class suburb of a politically corrupt state. People like hooks just blew my brain. It was thrilling.

I remember reading her work, and the work of Ruby Langford Gibni (Aboriginal Australian woman), Audre Lorde (black american feminist), Rita Mae Brown (American lesbian), and then Stuart Hall (queer black British cultural studies king). They were essential to my understanding of identity politics. Because I was a cultural studies person, I was also really influenced by film makers like Laura Mulvey (white British feminist), Lizzie Borden (black American radical), Tracey Moffatt (Aboriginal Australian artist), and by a bunch of authors.

I was lucky enough to be doing my BA in a huge english department (before media studies and cultural studies existed as disciplines), and that department included a lot of politically active feminists, poc, queer peeps, etc etc. So I was able to do subjects across a range of thinking within my BA. Goddess bless Gough Whitlam and the 1980s Australian university arts degree. I remember doing a lot of multiculturalism reading (in a postcolonial context), queer reading (a library full of books about sex!), and getting access to first nations activism. We had brilliant lecturers who were also activists in a lot of cases, and were culturally diverse. Nothing gets you fired up like a koori woman pointing at you and asking you what you’re bloody doing sitting there when there’s a rally to get to?!

All these people in the 80s and early 90, and their critiques of university-based white women’s studies (which was distinct from a lot of the feminist activism of the day), helped me understand that feminism can’t just be about gender. It has to address class, race, sexuality, etc, and it has to engage with institutional patriarchy. I was also influenced by Nancy Fraser (white American feminist) and her concept of ‘pragmatic feminism’. She argued that women’s studies had to have a practical, activist component (feminism) or it was just shoring up the academy.

But that was 20 years ago, and feminism has moved on. The lack of trans voices in the ‘feminist canon’ of that second wave is particularly telling. Even queer voices were marginalised at that moment. I personally think that the rise of trans politics within feminism has been the most radical change of this wave. And that’s no doubt why TERFs have so much trouble with it.

I think that these writers are important for understanding the history of feminism and gender studies, and for understanding women and activists of that generation (who are in their 60s an 70s now). But there are problems with them as well. And the nice thing about modern feminism is that it has moved on, adding new voices and thoughts to the discussion.

As a side note, I’m getting quite interested in Hannah Arendt and Seyla Benhabib at the moment. Old school feminists, but powerful thinkers.

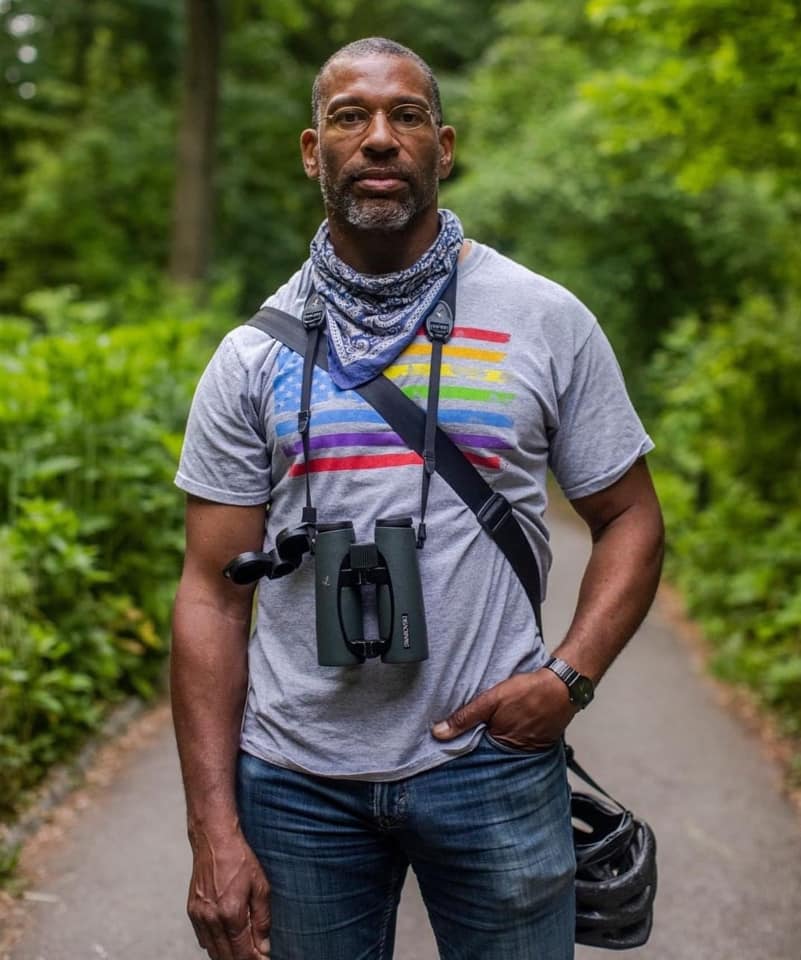

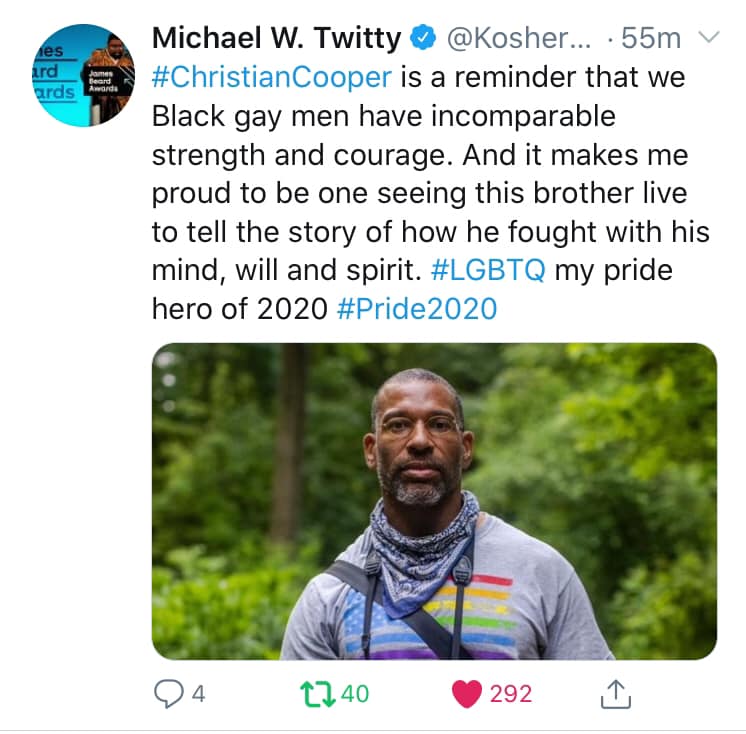

Black activist men:

Straight up, my most favourite thinker is Stuart Hall (queer, black, British man). His work on class, race, gender, and sexuality in culture was the most influential work I read when I was doing my MA and PhD. I love the way he wrote, and his ideas really resonated with me.

I was also influenced by Paul Gilroy (another black British thinker) for his radical black politics.

And I’m a big fan of Tommy DeFrantz (queer black American dance history scholar), who I met while I was doing my PhD. He’s a dancer and scholar, and the way he talked about black dance and media culture, as well as being a dancer himself, part of a dance community, shook me. Plus he is a kind man, and just the right influence I needed at that stage in my own work on race and dance.

I came across Raúl H. Villa and his work on the latina public sphere in LA in the late 19th and early 20th century and was fascinated (partly because it overlaps with the zoot suit riots stuff). I also got into Michael Warner (white American queer)’s work on the queer public sphere.

This then led me to another thought…

Academic journals and magazines were really important in that 70s/80s/90s moment, because they were often published by collectives, or by groups of scholars who had shared interests (and politics). They’d publish special issues, or articles with the latest thinking, and then in following issues authors would respond to those articles or issues. That meant you could see the thinking happening at the time in a particular journal.

So, for example, ‘Screen’ published Laura Mulvey’s article “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (Autumn 1975) in vol 16, issue 3 (pg 6–18), but people got so worked up about it (it was influential) that the next issue was themed, and all in response to her article.

There were also some really great magazines and journals published outside universities that gave marginalised writers a voice. eg On Our Backs (a sex positive lesbian erotica magazine) was a response to Off Our Backs (a feminist mag that was often anti-porn). For more.

When I first got to uni, I remember being kind of crazed by access to so many huge libraries. I would just sit in there reading everything. So. Many. Journals. I’d never even heard of things like feminist magazines or journals.

I know there are special collections of these things here in Australia eg Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives.

The language was exciting: very RISE UP! and radical activist.

And of course, at this point, it’s important to point out that Grey’s research and thinking can be read in Obsidian Tea, one of the most important publications in the modern lindy hop and blues dance world.