In this post I ramble on about Sydney’s DJing culture at the moment, particularly in reference to its social dancing culture and basic demographics. It began as a huge post, but has split into two. The second one (NEEDS MOAR DJS ? (part 2)) spends a bit of time talking about why DJing sucks and why I like DJing. At some point in the future I’ll try to write about how we might (despite all our better instincts) go about encouraging new DJs in the swing dance scene. I’ll begin this discussion with a blanket statement: Sydney’s swing dancers like live music. I’ve written quite a bit about it in this post ‘Swing Dancing’ and Lindy Hop in Sydney: an Exercise in Speculative Fiction. But we also quite like DJed social dancing nights as well.

I think there’s a link between a scene’s age and its use of DJs. New scenes rely on bands for social dancing, and only use DJs to fill in after class or in informal contexts. Yes? Hm. That seems a long bow to draw. But let’s leave it for now, and move on to another spurious declaration. Older scenes develop fairly complicated and professionalised DJing cultures and DJs. They also produce better DJs, usually people who’ve been dancing for a while, but not always. In recent moments, though, some of the older scenes in America have returned to live music in a big way (Seattle), and scenes in cities like New York and New Orleans are seeing increasing attention to their live music cultures from local and visiting dancers. In these scenes DJing has taken a more supportive (though still essential) role. Sydney dancers traveling overseas to scenes like these are bringing this idea back to our city: live music is good. Their online discussion and interaction with dancers from those overseas scenes reinforces the radical ideas traveling dancers bring home to Sydney. The idea that ‘live music is good’ (and ‘cool’) is also circulating in other Australian scenes, and reinforced when Australian dancers meet up at events or talk online.

For an awful lot of dancers, the idea of what they should like (as propagated by teachers, influential individuals (teachers, etc), the programs of high profile events, etc) is more important than what they might actually like. For example, most people find themselves, mid-dance liking dancing to LCJO’s ‘C Jam Blues’. But most dancers who’ve been around for a while don’t like the idea of dancing to it. Because it’s too overplayed/slow/bigband/whatevs. This fascinates the part of my brain that likes to think about taste and cultures of taste and the influence of various digital media. It can really frustrate the other part of my brain that likes to DJ stuff I like, which doesn’t always coincide with popular trends (enough goddamn tuba-shouting-banjo for Ceiling Cat’s sake! For pity’s sake, give me a little classic big band swing for my lindy hop!) But, for the most part, it’s difficult to argue with this fad. Live music: it is good. It really is.

So there’s something of a tension between DJed and live music social dancing in Sydney. They often attract different crowds and are managed by different ideological, financial and political forces.

Let’s talk numbers.

Sydney lindy hop demographics. There are about 4.5 million people living in Sydney (and about 4 million in Melbourne). Sydney is the largest city in Australia, though not the fastest growing. DJing isn’t one of the largest pools of labour in the Sydney lindy hop community – there are only about thirteen of us. There are about fourteen teachers working regularly and occasionally with the two larger inner city schools, and many teachers are also DJs. There are a bunch of other teachers with the other schools in the outer suburbs, but I don’t know them at all really (I’d put them, conservatively, at about ten teachers). Unpaid volunteers number anywhere between fifty and one hundred across the two larger schools (this is a difficult one to quantify). I have no idea how many people take swing dance classes in Sydney. Sydney has hosted two or three larger annual events in the past (dropping to one this year) and a number of smaller workshop weekends. There is a great deal of cross-pollination with the Canberra scene, which is only a three hour drive away. No other Australian scenes are so close together – most are at least eight hours drive apart (I am blurring Geelong into the outer suburbs of Melbourne).

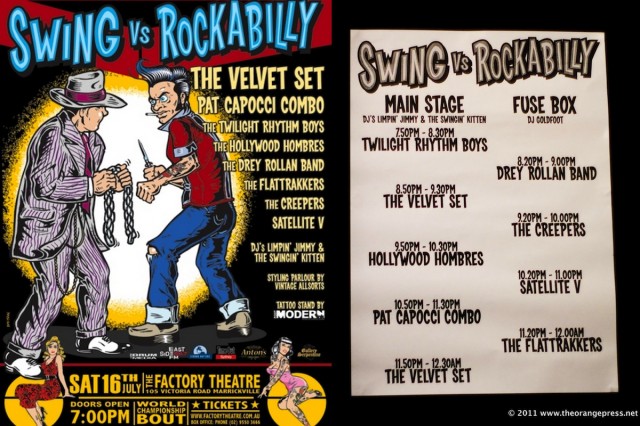

Sydney has lots of social dancing. Because we have lots of DJed social nights. We have three regular dancer-run DJed events: Swingpit, Roxbury, Jump Jive n Wail. JJW is mostly rock n roll, jump blues and neo swing, and it’s a gig managed by one professional DJing couple. It’s a majorly popular cross-over point between the rock n roll, rockabilly,’swing’ and lindy hop scenes. Roxbury and Swingpit are run by two different dance schoosl and are on fortnightly, on alternating weekends. Swingpit uses four DJs per month, Roxbury between four and six per month. They tend to draw on different DJing pools. Then there’s the new and irregular North Sydney after-class social dancing, which has one or two sets per month, give or take. DJs are also used for other occasional social dances – the (irregular) late night Speakeasy, band breaks for live music gigs run by dancers, and larger social dances run every now and then.

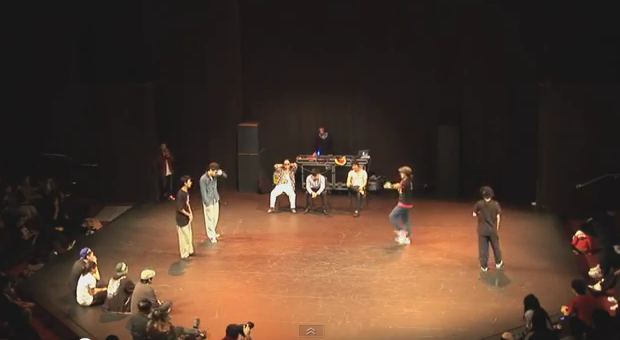

(Me, Ben and Kat, DJs for the SP performance ball this year. Not the most thrilling DJing gig; we may have been distracted by our own fun.)

Sydney’s complicated cultural architecture leaves us in a fairly tricky position when it comes to running DJed social dancing nights. Basically, we don’t have enough DJs to fill all our DJed social dancing spots. Our current venues use between ten and twelve DJ sets per month. That’s at least two sets per week. Of the ~thirteen DJs in our town, five DJ regularly and have solid skills. Only three of those DJ interstate, and only two or three would I hire for a big interstate event. We also have five DJs who DJ irregularly, but who would really rather dance. Two of the thirteen very rarely DJ any more (and haven’t in literally years). We have one or two or perhaps three or four who are really green. And then there are assorted blues DJs who don’t get to DJ anywhere any more at the moment, as our blues scene has pretty much collapsed.

When you look at the number of sets to be filled, those thirteen DJs don’t go too far. Some (like me) will do quite a few sets, but cap at about three per month. Most would rather DJ no more than once a month. Some are on complete hiatus.

At this point I simply can’t get enough DJs to fill the slots at Swingpit alone. This is partly because it’s November, and November is a busy month. Sure, people go nuts in December with parties and stuff, but in November people are really working their guts out at work. And Sydney can be an expensive town, requiring jobs that can be quite demanding. We’re also at the tail end of exchange season in Australia – there are about six large events in October and November, plus a round of christmas dances and festivals. So most of the DJs (and teachers and dancers) are kind of tired and burnt out. They just can’t manage DJing on top of everything else.

So we have lots of healthy social dancing nights, quite a lot of keen social dancers, but not enough DJs to do the DJed gigs. The obvious solution would be to put on bands instead of DJs. Bands pull numbers, and Sydney is busy proving there’s a clear market for live music events catering to dancers. So why don’t we just swap bands for DJs?

There are some financial issues at work. Neither Swingpit nor Roxbury could afford to put on a live band every fortnight. Both events are run on quite a tight budget, in part because they only charge $6 and $5 respectively for social dancing entry. That’s nothing. It’s hard to find a decent lunch for $5 these days, let alone a good night of fun dancing. An obvious solution would be to charge more for the social dancing nights, and to put on a band with the extra money. Two years ago I think you’d have had an outraged chorus of tightarsedness from dancers. But these days we pay anywhere from $10 to $40 for live music at venues with good dance floors.

Despite these brilliant(ly unthought out) arguments, there are a range of factors affecting the finances of these events which need to be taken into account. And even I know not to discuss these sorts of things in detail in public. :D

A shift to live music at our regular, dancer-run core social dancing events would mean a larger shift in the way social dancing events are run. Coordinating a band involves different skills and contacts than coordinating DJs. Bands need proper pay, and DJs are largely regarded as ‘hobbyists’ or volunteer labour. DJs are usually dancers and (preferably) know how dancers use music. Bands know music, but aren’t (in Sydney anyway) serious dancers, so they don’t know how dancers use music. More importantly, one gig for dancers a fortnight is not the most important thing in a band’s working life. They have other, more lucrative (corporate) gigs in their schedule. I think, however, the biggest and most difficult challenge in shifting from DJs to bands would involve prioritising music and social dancing, which organisations who make their money from teaching are not willing to do.

What if we did drop DJs completely and use bands instead? I’m not sure how things would go. I don’t think class-centred institutions like dance ‘schools’ could accommodate such hardcore ideological shifts. That’s a whole different way of thinking about dance and about profitable dance projects. An entire reshuffling of the social hierarchies and (commodified) knowledge values of a community. I think the modern Sydney lindy hop scene needs DJs, if only because it means that it doesn’t then need to reassess the value it gives music, and the knowledge and financial economy of the scene as a whole. Such a major change would involve a lot of ground-level effort, which Sydney isn’t really built for. Not at the moment. But even with an increased emphasis on live music for dancer-run events, there’d still be a place for DJed social dancing, if only on a smaller scale.

Let’s pause for a moment, and think about me.

What would I like? In a perfect world there’d be social dancing every week. Twice a week. At least. By social dancing, I mean spaces and events that are perfect for dancing. A decent floor that’s not covered in drunks and broken glass. They could be with live bands. That’d be cool. But I’d be ok with a really good DJed event as as well. So long as they were really good DJs. To be honest, in my perfect world, we’d have a DJed dance once a month that featured only really top notch DJing, was held in a dance-centred space (like a not-too-big dance studio) with an excellent, appropriate sound system, with a bar next door or attached or something so we could get drinks or noms. But the dancing would be the most important activity. And by good DJing, I mean mad crowd working skills and excellent solid swinging jazz. No neo. No rock n roll. No fucking novelty songs. Just 1920s-1950s classic swing and modern recreationist bands. Combined cleverely by a DJ who’s watching the floor. Four hours of that once a month, and I’d be happy. I’d complement that with lots of dancing to live bands each week. Unity Hall on Sundays. A Friday night band in a fun venue like the Camelot Lounge. Saturdays at different one-off events with different bands. A different band (or two) each week.

I’d be quite happy retiring some of our DJed social dancing sets. My DJ skills would slide a bit, but I do DJ interstate quite a bit, so I’m not really all that sad about it. And, by gum, I’d much prefer dancing to DJing myself! Right, now I’ve almost convinced myself that crying “DJ drought” is really my missing the point. Perhaps it might be more useful to rethink a (short sighted, isolationist) DJ-centred approach to social swing dancing culture. It seems a better idea to integrate live music more thoroughly into our everyday dance activities, to reduce our DJed dancer-run events and present entirely new types of dancer-run DJed events.

So, really, is it so sad to lose DJed social dancing? Hmmmm…..

I’m going to continue this discussion in another post, as this one is way too big already. The second part (NEEDS MOAR DJS ? (part 2)) will talk about the frustrating parts of DJing and this ‘DJ drought’.

[EDIT: This is one of a number of loosely-associated posts about music in Sydney lindy hop today. This list includes:

- ‘Swing dancing’ and lindy hop in Sydney: an exercise in speculative fiction (Thursday, November 10th, 2011)

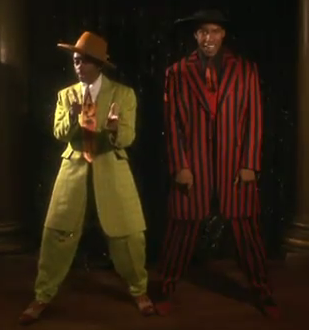

- zoot suit riot (riot) (Thursday, November 10th, 2011)

- NEEDS MOAR DJS ? (part 1) (Thursday, November 17th, 2011)

- NEEDS MOAR DJS ? (part 2) (Thursday, November 17th, 2011)

]