I’m working on a new project at the moment. Or rather, I started working on this project years ago. It’s still not finished, as you’ll see. But I figure: get it up now, or it’ll never see the light of day.

It began with my Women’s History Month posts in 2011 and has been sloooowly, sloooowly proceeding from there. Eek. Now I look at it, this is three years’ worth of work. Not consistent work, by any means, though. But work, none the less.

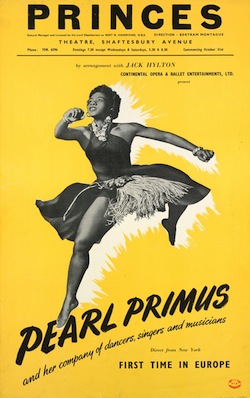

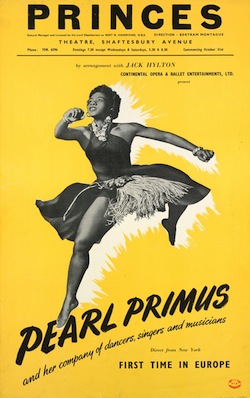

In March 2011 I started posting a different woman jazz dancer every day on facebook, and then cross-posted them to my blog each day as well. People dug them, and I found I was learning a LOT about jazz dancers.

The next year, I decided to do the same for the 2012 Women’s History Month. Except this time I posted a different woman jazz musician every day of the month.

In 2013 I went back to women jazz dancers, posting a different woman every day for Women’s History Month in March 2013, some repeats from 2011, some new.

All these women jazz dancers posts took quite a bit of research. I started with the obvious ones, but as the month progressed, I needed more. So I hassled my jazz researcher friends (people like Peter Loggins), and I started hunting down women in film clips.

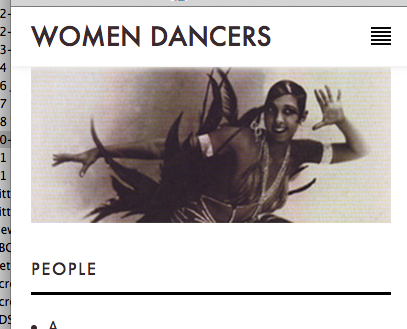

Well, I built a website to showcase all my Women’s History Month posts, but it was a bit rubbish. For a start, it wasn’t using responsive design, so you couldn’t look at it on a mobile. But that wasn’t really my fault – it predated my experimentation with responsive design.

This past month (December 2014), I decided to update the website, make it properly responsive. This overhaul was inspired by workshops and conversations with Marie N’Diaye over the Jazz BANG weekend. Marie’s chorus line project in Stockholm is really exciting. She really opened my mind about women chorus line dancers, and I decided I needed to share the research I’d put into this project.

And I had put a lot of research into this. It seemed a shame to let it go to waste.

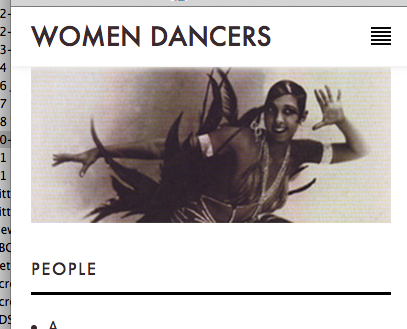

Women Dancers From Jazz to Bebop is a reference tool. It’s not an exhaustive biographical tool. It really just provides the names, birth dates, and any film and stage show appearances I could confirm. If I could find a photo, I’d include that too. I cross-checked all the details as thoroughly as I could, and if I couldn’t confirm something by double-checking it, I made that clear.

I found quite a few errors in references like the internet Movie Database, and found new uses for my music discographies. Fully nerd. But I wasn’t alone – I really did irritate all my dance historian friends, chasing down names and asking them who such and such is blah blah film was. I couldn’t have pulled this off without their help. You can read all my thank yous on the ‘About’ page of the website, but once again, I have to give Peter Loggins mad props: he has endless patience, and just gives and gives and gives.

The updated Women Dancers website has a better colour scheme, and you can actually read it on a mobile. Or a desktop. Or an ipad.

Why doesn’t this site host film footage itself?

One basic reason: too resource hungry. It takes too much room and time to host footage. And it’s a copyright nightmare. I’ve crossed some lines using photos, but it’s hard to make this site useful without pictures of the dancers – you have to know who you’re looking for when you start looking at archival footage.

How could you use this site?

Take a name from the index page, see what films she appeared in, then do a search for it on youtube. Then watch her dance, and teach yourself the steps she’s doing. You will probably suck a bit, but everybody sucks at first. Don’t stop there – practice, practice, practice. Get your learn on.

How will I use this site?

If you have a look through the index page, you’ll see that quite a small proportion of the dancers actually have live pages in their name.

This is because it takes aaaages to

a) research each woman, and then

b) code up a page for each woman.

I know, I know, I should have used a blogging tool for this bit, but I didn’t. I fail.

I’d like to use the sources in this site to do more research on good solo dancing. I’d like to get a bit more involved in some sort of chorus line project, and I’d like to put the research to practical use in our weekly solo jazz classes.

I had planned to build the database myself, as I was learning how to make databases in the postgraduate diploma of information management that I was enrolled in at the time (yes, another postgraduate degree – a grad dip in info mgmt, completed December 2011 or 2010 – I can’t remember which.) But I didn’t. The site itself really reflects the sort of site and reference tool design that dominated that course. A bit too much under-funded, ugly public service website design.

I’ll probably continue to tinker with the site, adding names and pages as I get time and inspiration. Do feel free – please do! – to send me new names and details. But I’ll need some sort of references or sources to cite before I add them to the site, I’m afraid.

In the mean time, I hope you find this site useful – get dancing, you women!

But I’m more interested in it as an aspect of the everyday lived spaces, in the way they’re talked about by people like William H. Whyte in The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. Whyte is kind of old hat these days, and has been superseded by more recent, more nuanced work, but this little film ‘The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces (1988)/ is pretty interesting if you’ve not come across this sort of work before:

But I’m more interested in it as an aspect of the everyday lived spaces, in the way they’re talked about by people like William H. Whyte in The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. Whyte is kind of old hat these days, and has been superseded by more recent, more nuanced work, but this little film ‘The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces (1988)/ is pretty interesting if you’ve not come across this sort of work before: