Neutral tones and natural fibres are de rigueur for the chic in Seoul this season. Straw hats and bags, leather sandals. Loose smock dresses, wide-legged cotton trousers. This most urban of urban cities is embracing a pastoral aesthetic, and they won’t let a little rain (and the threat of transparency!) dissuade them.

Seoul Fashion Report

The Sport Sandal. One of our favourites, because nothing says athleticism like exposed toes. Soles are thick and bouncy, colours are bright and diachromatic, straps are fat and ready for action. Ready, steady, go!

Seoul Fashion Report

Summer is for sandals, and this season Seoul is saying Hola! to the huarache. Complex braids or simple straps, leather to suit the natural fibre trend, or black and manmade fibres for an urban edge. However you choose to style this look, hurry, because they are flying off the shelves!

Seoul Fashion Report

Couples in matching ensembles is one of our favourite trends. Most usually the purview of the younger set, attention to detail is key. Matching shorts, heavy sandals, and wide-striped tshirts are trending, and after all, when one has a chic look, why not double it?

Seoul fashion report

Linen linen linen.

Summer is hot and humid in Seoul, and nothing’s quite as nice as an open weave on overheated skin. Wear it loose and relaxed; drifting open silhouettes for dresses, untucked and open-necked for shirts. And if you can’t find a neutral shade to suit, go wild with colourful jungle prints.

Gendered language in class

I’m ok with talking about gender and using gendered pronouns in class. I just like to be sure I’m not just using the same two boring pronouns all the time, and that I’m using people’s preferred pronouns.

I’m not ok with gendering leading and following, or skills related to leading and following.

This is partly why I’m not ok with some elements of the ambidance movement: I don’t want to do away with all gender.

But I do want to do away with the essentialist coupling of skills and ideas with two gender ‘norms’.

How then do I work to deconstruct gender in lindy hop when I’m teaching?

1. Use the words ‘leads’ and ‘follows’ (or the role name, and I’m with Dan when it comes to avoiding leader/follower) rather than ‘ladies and gentlemen’, ‘men and women’, ‘she/her/he/him’ etc etc.

2. Use people’s actual names rather than the role. It’s nicer generally, but it also encourages us to think of people as individuals, not roles. I try to use my teaching partner’s name.

3. Rather than talking about or around your teaching partner (eg “The follow will do this,”) speak to your teaching partner, asking them to describe what they’re doing (eg “How do you know I’m asking you to move forward, Alice?”).

Then there are trickier, less obvious things.

1. Always ask permission before you touch someone. It’s quite common for leaders to simply ‘grab’ a follow in class/their partner to demonstrate on them as though they were an object. I always try to ask them if I can touch/demonstrate. And I always apologise if I’ve just thoughtlessly grabbed them.

I started doing this after we started asking students to always introduce themselves and ask someone to dance before touching a new partner. It rubbed off on me :D

This stops us treating our partners like objects/just ‘the follower’. And this issue happens more with leaders grabbing follows than vice versa.

2. Conceptualising lindy hop as something other than ‘leader says, follow does’.

We are currently using ‘call and response’ and both partners can do it. We also use ‘leader invites follow to do X, follow decides whether to do X, how fast to do X,’ etc etc etc.

3. Don’t use words that position follows as objects.

eg never using words like ‘push’ to describe what leads do: ‘the leader pushes the follow’. No. This a) not technically accurate, and b) disrespectful.

4. Always try to talk about and think about your partner as a human with feelings and emotions.

When we get really technical, it’s easy to reduce our partner to an object force/momentum happens to, or a subject who generates force/momentum. We are real people with real feelings. So while physics is at work, our feelings and emotions are much more important. So we use language that describes what’s happening from that POV first. In nerd terms, this means using ‘external cues’ rather than ‘internal cues’.

eg. I ask Alice if she’d like to go to the snack table, then I take her hand and go with her to the snack table. vs ‘I hold her hand with my fingers in X position, then I engage my core, prepare, and then lift my left foot, swing it back 20*, place it back behind me, and then she engages her core and activates her frame…..’

The technical jargon encourages us to talk about our bodies and partners as technical objects, not as real live humans. It also slows down learning :D

5. Speak and act as though your partner and other dancers have opinions, and that these opinions may differ from yours.

We often try to hide the way we ‘make the sausages’, but it’s more useful for learners to see us discuss things, perhaps disagree, share different ideas. So ask your partner and students what they think and feel. Allow yourself to learn from your students and be surprised and delighted by this new information.

-> all this stuff is about deconstructing not just a gender binary, but a hierarchy of gendered power with straight white bro at the top.

And what of historical accuracy in all this?

I think it’s important to talk about gender in a historical context when we talk about lindy hop. So while a gender neutral pronoun is very much something white, middle class Australian teachers are experimenting with, that’s not how black dancers might have spoken of each other in the 30s.

Again, though, I like to take care about generalising. While some dancers today would have us believe that the 30s were a time of rigid gender norms, that’s not entirely true:

– There were women leads and men follows (and every gender ID ever) in the olden days,

– There were queer dancers and musicians (I’m currently reading about queer culture in NY in the 20s-40s… helllooooo genderflex ID and jazz dance!) and genderflex lindy hoppers fucking up the patriarchy then. Lester Young, anyone?

– Some of the most supportive teachers I’ve had have been black OGs, who’ve used gender neutral language and openly said they support women leads/male follows/genderflex dance IDs.

So when we talk about ‘ungendering’ lindy hop, that’s perhaps not helpful. It’s more that I want to widen my understanding of gender (and sexuality) in dance to more than just straight men leading and straight women following. The world is huge, and jazz asks us to improvise and innovate.

I have written about this many times before:

Selling dance products by promoting self-doubt

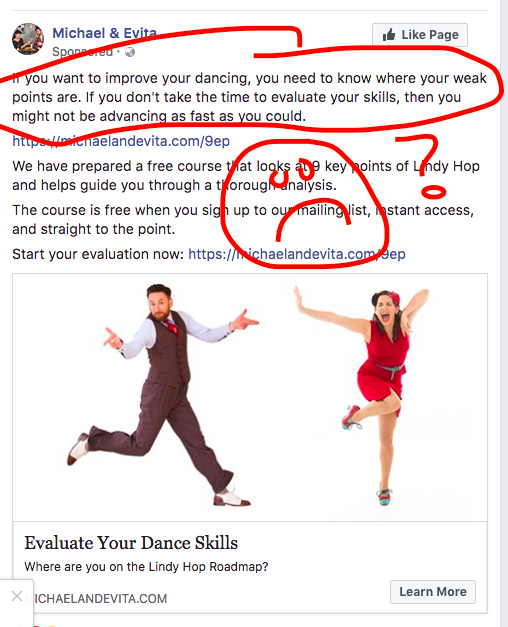

I see this ad about a bit on fb, and it makes me so sad.

“If you want to improve your dancing, you need to know where your weak points are. If you don’t take the time to evaluate your skills, then you might not be advancing as fast as you could.”

This is classic provoking anxiety to stimulate consumption advertising. Make people doubt themselves, feel bad, then offer them a solution.

This is everything I don’t want to be as a teacher.

Why not take the time to remind yourself that you enjoy dancing, that you have strength and skills and abilities? We know that happy, confident students learn faster and more thoroughly. But we also know that anxious, self-doubting consumers spend more money on luxury items to boost their self esteem.

Boo to this. Boo.

Moving away from gender essentialism in teaching talk

In a recent facebook talk about teaching and gender in lindy hop we took the next few steps past not using gendered pronouns to describe leading and following. We then went on to look at how people gender particular dance styles or movements in essentialist ways.

Here are some comments from that discussion.

I’ve had teachers ostensibly ok with non-binary/non-bro peeps leading, then unable to even look at me when we split into lead/follow groups in class.

But there are definitely teachers around who are good at dealing with their own errors and then fixing them. eg Georgia and Kieran.

I am definitely on board with the goals of uncoupling leading and following from gendered archetypes. I’m personally not interested in switching roles mid-dance, but I do lead and follow, and think of the two roles as functioning in very different ways.

I was interested at a recent weekend workshop to hear/see Kieran talking about ‘attacking’ a rhythm to make the lead/follow element work. This is often a word associated with masculine archetypes. But he was asking leads _and_ follows to try this. Which effectively asks all peeps to try on this masculinised characteristic, ‘even’ while following. Which then reconstructs following as involving stuff outside archetypal femininity.

Even more interestingly, Georgia asked us at later point while we were playing a game where you copy your partner’smovements/rhythms without touching, to ‘not hesitate’. She asked not to pause and worry about being right, but to continue through.

Same concept as with Kieran’s comments, but different language: confidence, continuing despite lacking certainty. This is particularly important for women, who are trained to self-doubt or try desperately to ‘please’ their partner.

I think this approach – describing one skill in a range of ways – helps deconstruct the gender norms at work in our ideas about leading and following.

And I think ethnicity and class are key in this. Eg white, m/c, younger women are trained to self-doubt and not ‘attack’ movements. So we might also look at the dancing of Anne whatsit from Whitey’s as an example of a woman who really attacked rhythms.

Alex asked:

Have you seen the opposite? Teachers asking all students to try on feminized characteristics? With anything like the same frequency? I’m not sure I’ve ever considered this topic in this context, but I’m aware of the phenomenon of attempting to address gender inequity simply by offering masculinity to women and girls but not doing the same with femininity and men and boys.

And I replied:

yerp, marie n’diaye talked sbout it explicitly in the chirus line stream at herrang last year: asking people try ‘masc’ and ‘fem’ styling.

Other than Marie, nope. I know lots of men/non-woman-IDing peeps who dance femme, but no teachers asking all students to try.

Ask men to dance femme? Their penises would fall off, right?

Alex then made some more really good points:

And I guess that wasn’t quite what I was asking. If I understand correctly, the teacher you referenced above didn’t ask students explicitly to try something masculine, but he asked students to attack the rhythm and you picked up on the gender association. My guess is that it’s more common for teachers to ask students to so things or adopt characteristics associated with masculinity (attack the rhythm, be assertive, take over) than it is to ask them explicitly to “do this masc.” So I’m wondering about the presence and frequency of calls for students to take on feminine characteristics or engage in feminine activities, rather than being asked to “do this femme.”

Now that I’m thinking of it (and talking with Samantha) we do this a little. Telling our students to pretend that their partner is a terrified newbie and to take care of them is an example. I’d like to think about this more and see where else we can do this. For instance, I see plenty of people attack the rhythm. I’d like to see them treat it gentle more. Nurture the rhythm.

And like… How far can we take this? Gestate the dance. We’re just out of the intro, if you try to birth it now it won’t make it. And don’t feel like it needs to be big. You’ll tear.

Then Magnus chimed in with a good comment:

Yes, Marie N’diaye showed us examples of dancing “feminine” and “masculine”, and we tried dancing the different styles. She also talked about how some famous dancers back in the day would dance feminine or masculine opposite of gender, although they wouldn’t call it that (Cab Calloway for instance).

To me, I don’t connect these styles with feminine or masculine, these words are just cultural constructs. But it feels good to dance in a style that some people may deem feminine.

I think this is what’s key for me: these characteristics are just characteristics or qualities. They only become ‘masculinised’ or ‘feminised’ in a wester cultural setting that uses gender binaries.

I keep thinking about other cultures where there are more than two gender roles, and how these variations offer us so much more creative room than a boring old gender binary.

I also agree, Alex, that we tend to see masculinised qualities prioritised/valued in an anglo-celtic western culture. That’s pretty much the definition of patriarchy right there.

Other ways of describing stuff that isn’t masculinised that I’ve heard teachers used:

- Lennart has described having clear rhythm as ‘eating the rhythm’. With our students, we say “eat the rhythm, swallow it down, and now it is in your belly, right in your belly.” It’s a very useful image, because it also encourages groundedness, a physical vs cerebral understanding of rhythm, an idea that the core/our pelvis is the birthplace of rhythm (how’s that for gynocentrism? :D ) and is just nice.

- Rikard and Jenny and peeps like Ramona talk about it as ‘taking care of the rhythm’, and Lennart talks about ‘taking care of the music’. I like to say ‘make friends with the music’ and ‘take care of the rhythm’. This idea of ‘taking care’ and congeniality is really nice because it’s a nice contrast to that ‘attack the rhythm’ model. _But_ the attack the rhythm image does give you an impetus and energy that ‘take care’ does not.

- I like to talk about dancing every rhythm or every step as though I’m teaching it to my partner, or demonstrating it so well that they can pick it up and then dance/steal it too. This of course grew from my own teaching guiding my dance practice, but we found games like i-go, you-go reinforced this model. If you are dancing as clearly as you can, as though you are showing someone, you dance really clearly, _and_ you connect with a partner. This makes dancing a way of connecting with a human (reciprocity) rather than just artistic self-expression (individualism).

I’d be super curious and really excited to see how people from different cultures describe and imagine dancing clear rhythms. I mean, the whole shift from ‘doing footwork’ or ‘good technique’ or ‘clarity of movement’ TO talk about rhythm, call-and-response, etc etc, in American/Anglo/Australian/Canadian lindy hop discourse is evidence of a clear ideological shift. A shift away from a very antiseptic lindy-as-science, towards lindy-as-art, lindy-as-social-connection. I know that it’s very tempting to see this shift as proof of a shift towards positioning lindy hop as vernacular dance (again), but I’m not convinced. All this _talk_ about dancing in class is simply another way of doing what middle class, white capitalism has been doing with dance for a century or more: commodifying dance with particular words and discourse.

what even is 32 bar chorus v blues phrasing?

Swinging jazz is really formulaic and predictable. This is mostly because of the constraints of the recording industry: the 3 minute pop song is all that fitted on one side of a record. Which makes it great for improvising with. Live music is very different, and was very different.

This is partly why dancers should dance to live music: it’s less predictable, and you really have to pay attention, in case someone adds something.

This predictable formula is also why peeps get so shitty with DJs who play awkwardly phrased songs in comps: you have to really work hard to ignore the structure of a standard swing song.

I actually like to sit down and draw out the structure of a song if I’m thinking about choreographing or using it for a routine. It really helps me understand to see a ’32 bar chorus’ written out – that’s 16 lots of 8. Which is 4 phrases. You can teach that in an hour. My ‘thinking brain’ likes me to do this to help me become conscious of some things in a song. Especially with tap. But my ‘dancing brain’ gets confused and flustered if I try to count or think about the markers of phrases and choruses consciously, so when I’m dancing (esp social dancing), I don’t think ‘here comes the phrase!’ I listen to the music, and let the musicians tell me when a phrase is over or a chorus is beginning. eg a solo might go for a phrase, or a particular musical theme might go for a chorus.

The shim sham is 4 phrases (3 basic phrases + an added phrase), and that helps me think about the relationship between dancers and bands in the olden days. A dancer would get up and do a chorus, then bow out.

You can also hear it in a standard swing ‘pop’ song: the main ‘story’ of the song is in that chorus.

A really standard pop song will play 4 choruses, with some intro or outro stuff or perhaps a bridge or something somewhere.

If you’re listening to a nola type song, or something like Fats Waller’s Moppin And Boppin, you can clearly hear the choruses, with a final shout chorus:

– there’s an intro-type bit with drums (Fats shouts out “You want some more of that mess? Well here tis, Zutty take over – pour it on ’em!”) and then Zutty plays about 3 phrases (2.5 really).

– then the band kicks in with the main ‘theme’ of the song for a chorus, with everyone playing together sensibly.

– then there’s a chorus with lots of solos

– round about halfway Slam Stewart does 16 phrases (a chorus) on the bass with some humming.

– Then Zutty Singleton does a chorus on the drums.

– Then there’s a final chorus where everyone joins in, which ends up feeling a lot like a ‘shout chorus’. A shout chorus is a big, exciting end part, where all the musicians get crazy. If I’m DJing, I know that if I hear that shout chorus, I need to get my next song sorted.

Because it’s Fats Waller, that ‘starting sensibly then getting crazy’ vibe is a clever play on the predictable 32 bar chorus structure: he takes you on a journey.

All of this feels really nice and balanced:

– 4 choruses plus a shout chorus at the end and an intro at the beginning.

This is the structure that makes swinging jazz so nice to lindy hop to: it’s predictable. It means a dancer can step up with a band and take a chorus and know when/where to come in.

I’ve been doing some work with a band lately where I have to MC/narrate stuff during a song, and while I know all this with my brain, in the moment I get a bit flustered, so I watch the band leader who cues me with a nod. A band that plays head arrangements (vs using sheet music) develops a nonverbal language of nods and so on that cues each other in. There was actually a whole language of nonverbal cues that big bands used to use, but of this language isn’t used any more and is lost :(

Ways to learn this stuff:

– with paper and pen;

And, much more usefully, with your body, so you can turn off your counting brain and let it work on choreography or being creative:

– Dancing the shim sham to different songs. You figure out which songs are blues phrased pretty quickly :D And you realise why Ellington was so wiggedy wacked.

– Calling the freezes, slow motions, and dance! in a shim sham. It feels really natural do to it on the phrase, but a whole phrase at 120bpm is boring, so you do it at half way points.

fashion docos

I’m nuts about fashion docos, and this week I saw First Monday in May, about the Met’s gala, and specifically, about the China Through The Looking Glass gala. It’s a clever bit of documentary making. I was really digging the way it set up the discussion of orientalism/racism at work in the exhibition… or was it all a clever sensationalist PR tool?

I’ve also watched Bill Cunningham New York, September Issue, Diana Vreeland: the Eye Has To Travel, Iris*, Advanced Style*, Unzipped, Fresh Dressed… I love them all. And Harold Koda is in all of them.

I love the marriage of documentary film and the little diatribes about fashion as art/fashion as truth/fashion as sociology/fashion as real life. But I don’t have time for whole television series or reality television. Just films. I’m also fascinated by the same few figures turning up in each of them – Anna Wintour, Bill Cunningham…