…and the last of my Big Binge CDs arrived today, along with a lovely needlepoint pack. It was just like christmas.

Let’s start with the needlepoint. I bought it from this slightly dodgy looking site. I’ve recently gotten returned to needlepoint, c/o a christmas present Margarate Preseton job, and have gotten a bit obsessive about it. Had to have another to do, though I’ve managed to sate some of that obsession with a nice blue patchworked crocheted blanket for The Squeeze – I can’t bear large crochet projects in summer, but the smaller squares are easier – remind me to post pics of my fabulous red flowered job. Note the price – $55 for printed canvas + all wool. That’s not bad at all. And it’s an Australian company, so there’s less postage to pay.

Jimmy Witherspoon with Jay McShann Goin’ to Kansas City Blues from Mosaic. I’m a big fan of Jay McShann, and while I don’t like Witherspoon’s politics, he can sing like a mofo. I’m still keen on that big, fat 50s sound. This one has lovely quality recording, and the band is so freakin’ good (Emmett Berry, J. C. Higginbotham, Hilton Jefferson, Seldon Powell, Al Sears, Kenny Burrell, Gene Ramey and Mousey Alexander). Some of it veers off into post-swing (this is a 1957 recording after all).

Jimmy Witherspoon with Jay McShann Goin’ to Kansas City Blues from Mosaic. I’m a big fan of Jay McShann, and while I don’t like Witherspoon’s politics, he can sing like a mofo. I’m still keen on that big, fat 50s sound. This one has lovely quality recording, and the band is so freakin’ good (Emmett Berry, J. C. Higginbotham, Hilton Jefferson, Seldon Powell, Al Sears, Kenny Burrell, Gene Ramey and Mousey Alexander). Some of it veers off into post-swing (this is a 1957 recording after all).

Most of my Jay McShann is earlier – nice, dirty Kansas City stuff. Though I do have this album Hootie!, a live job by his trio in… damnit, I haven’t entered the date! [EDIT: just checked it – it’s 1997] And the CD is far away… Anyhow, that’s a great album, but it’s supergroove. Lots of long, tinkly songs with tinkly piano, often at supersonic speeds. Not really the best dancing (except for the odd blues track), but really good listening music. I really like McShann’s piano style – it’s so different to people like Basie and Ellington and Junior Mance and Oscar Peterson.

So, anyhow, this new CD is really fun. Lots of great, upenergy songs. As I said, though, it’s a bit post-swing, in that it stops swinging quite so much. The slower ones are better, but the uptempo ones are kind of staccato or abrupt. Don’t swing so much. What this means for dancers is that it feels like you’re rushing from beat to beat, and that songs feel faster generally. This can be good for lifting the energy in the room every now and then (especially if it’s a more recent recording), but ultimately, it does bad things to your lindy hop. We need that gushy, delayed timing to really make us swing, to keep us hanging back and soaking every last moment out of each beat.

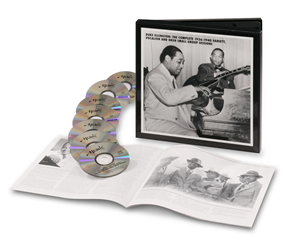

My other lovely present is Duke Ellington: 1936-40 Small Group Sessions, another Mosaic set I’ve had my eye on for ages. Cost a freakin’ bomb, but oh-baby, I have a serious thing for Ellington that’s just not going away. I have quite a few Ellington CDs and collections, but I couldn’t resist some lovely Mosaic remastering goodness (that’s what makes these expensive things worth it – good remastering, not to mention fab liner notes and packaging and great service).

My other lovely present is Duke Ellington: 1936-40 Small Group Sessions, another Mosaic set I’ve had my eye on for ages. Cost a freakin’ bomb, but oh-baby, I have a serious thing for Ellington that’s just not going away. I have quite a few Ellington CDs and collections, but I couldn’t resist some lovely Mosaic remastering goodness (that’s what makes these expensive things worth it – good remastering, not to mention fab liner notes and packaging and great service).

This is completely different stuff to the Witherspoon CD – 20-odd years earlier, different approach to the rhythm section, very different approach to composition/arrangement. Really, this is a nice comparison between classic 30s swinging jazz and the ‘next generation’. While I adore the Witherspoon/McShann CD, this is where my heart truly lies. I love Ellington for the complexity and sophistication of the arrangements and plain old management of the band. Each musician has a very particular job, and they do it just wonderfully. I also prefer this bouncy old school sound – makes me want to lindy hop. None of that shuffle-rhythm going on in the drum kit area. Nice shouty choruses at the end of songs. Yes, please.

I also like these big ‘complete, collected works’ sets because they include multiple takes of the one song. This means you get to hear the band make minute variations in the way they play, and you really begin to understand how the band work together as a team, and how a slightly shorter solo can change the whole song. I also like hearing the people in the studio talking – it’s like we’re just that little bit closer to a world that feels imaginary, most of the time. They way they talk, the things they talk about – are all so far away from us. But when you hear them swearing about fucked up takes or laughing at jokes, it becomes a bit more real.

So, sitting up in bed looking through all these goodies this morning (it was an early delivery), it felt like my birthday. And it was lovely.

Now I just have to score a few more DJing gigs to cover these extravagances.

Category Archives: music

slim gaillard’s Laughing in Rhythm and Fats Waller and his Rhythm, the Last Years 1940-1943

Two new arrivals:

Slim Gaillard’s Laughing in Rhythm. Can’t believe I’ve only just bought this. I am so the slowest, uncoolest DJ on the block. I mean, I’ve bought bits and pieces from places like itunes, but still. It’s a bit late. I’d still like the giant Gaillard Proper set, but I just can’t bring myself to buy all that nonsense singing…

Slim Gaillard’s Laughing in Rhythm. Can’t believe I’ve only just bought this. I am so the slowest, uncoolest DJ on the block. I mean, I’ve bought bits and pieces from places like itunes, but still. It’s a bit late. I’d still like the giant Gaillard Proper set, but I just can’t bring myself to buy all that nonsense singing…

Fats Waller and his Rhythm, the Last Years 1940-1943. I now own about 60 million Waller CDs. And I’m not quite sure that’s enough.

retuning for white audiences – more sister rosetta tharpe

Helen has asked for specific details about the tuning of Tharpe’s guitar in her comment here. Below is a big fat quote from an article called ‘From Spirituals to Swing: Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Gospel Crossover’ by Gayle Wald (published in ‘American Quarterly’, vol 55, no.3 September 2003), pgs 389-399. This is where I read that note about Tharpe’s tuning – hope it’s useful, Helen.

Wald’s article is mostly about Tharpe’s movement from black gospel music to the white jazz/blues/pop mainstream. Tharpe is taken as an example illustrating wider points about culture and music during this period. It’s a really interesting read.

Although Tharpe arrived in New York already highly credentialed in Pentecostal terms, Sammy Price, Decca’s house pianist and recording supervisor at the time Tharpe recorded “Rock Me,” apparently wasn’t feeling any of this joy. Tharpe, he recalled in his 1990 autobiography, “tuned her guitar funny and sang in the wrong key.” In all likelihood Price was referring to Tharpe’s use of vestapol (sometimes called ‘open D’) tuning popular among blues musicians in the Mississippi Delta region. (Muddy Waters is among the many blues guitarists, for example, who learned vestapol technique in the 1930s, when he was growing up in Clarksdale, Mississippi.) As common as it was in the South, however, vestapol tuning could sound distinctly crude and out-of-place in the context of northern jazz bands. By his own account, Price, who later went on to record several hits with Tharpe, refused to play with her until she used a capo, the bar that sits across the fingerboard and changes the pitch of the instrument. “With a capo on the fret,” he explained, “it would be a better key to play along with, a normal jazz key.”

Price’s brief story of the carpo as a normalizing technology is rich with implications for the discussion of what ‘crossing over’ to the realm of popular entertainment might have meant for Tharpe. Resonant of southern black communities and of musicians who honed their craft in churches as well as on back porches – musicians Hammond quite unself-consciously called ‘unlettered’ – Tharpe’s ‘funny’ guitar playing introduced, to Price’s ear, an apparently unassimilable element into the prevailing sounds of urban jazz. It’s also possible that Price was demanding that Tharpe sing at a higher pitch, to conform with popular as well as commercial expectations that high pitch evidences a correspondingly ‘higher’ degree of femininity. In any case, and as Price suggests, Tharpe quite literally had to adjust her guitar and singing techniques to make commercially popular, ‘secular’ records that would earn her an audience beyond the relatively small market of consumers of ‘religious music.’ The ‘makeover’ of Tharpe’s sound also has important gender and class implications less obvious from Price’s comment. In bringing her sound more into line with the sounds of commercial jazz, Tharpe would not only have to change her tuning, but ‘change her tune’ as far as her performance of femininity was concerned.

The ‘Hammond’ referred to in the article is John Hammond, an important figure in the promotion and management of a number of big jazz musicians. Gunther Schuller’s book ‘The Swing Era’ reads almost as a history of Hammond’s career. I think it’s important to note that this one white man was important for his influence on the developing jazz and swing music industry. His selection and then promotion of specific artists shaped the recording industry, popular tastes and the white mainstream’s understanding of and access to black music during this period. As the race records and black-run radio stations were forced out of the industry by white competitors and blatantly racist media regulation, black artists had less and less control of their own representation in mass media, and black musical culture was mediated by white corporate and cultural interests.

All of this makes for fabulous, fascinating reading. It is, though, all about America. I’m not sure how much (if any of it) can be translated to the Australian context. But that would make for interesting research in itself, particularly when you keep in mind that jazz in Australia is necessarily the product of cultural transmission – black music filtered through mainstream American recording and sheet music industries to white mainstream audiences and musicians and white Australian musicians and audiences. Sure, there were musicians making jazz in Australia (people like Graeme Bell of course), but I’ve been thinking about ‘authenticity’ and jazz in such a transplanted context… particularly as I’ve read recently somewhere (goddess knows where – I’d have to retrace my steps) that music tends to reflect the vocal patterns and intonations and rhythms of the culture in which it develops. So, we could draw from this the conclusion that we Australians would play jazz with an Australian accent. It wouldn’t sound like American – or black American – jazz. I’m hesitant to make comments about the relative value of localised jazz, but it’s an issue hanging in the background there…

But back to Hammond. John Hammond of course organised the concert ‘From Spirituals to swing’ at Carnegie Hall in New York in 1938 (you can see the artists here, in a recording of the concert) . This concert featured a bunch of super big artists (Jimmy Rusher, Joe Turner, Mitchell’s Christian Singers, Albert Ammons, Sidney Bechet, Count Basie, Benny Goodman). It’s goal was a combination of musical ‘education’ for the white mainstream and – indubitably, considering Hammond’s impressive business sense – promotion of black music to new white audiences/consumers.

I’m interested in this concert and in Tharpe’s cross-promotion to the mainstream as an example of cultural transmission – I’m fascinated by the way music and dance move between cultures. I’m also really interested in the uses of power in this process. Is it appropration? Stealing? Poaching? To quote (ad nauseum), Hazzard Gordon, we have to ask “who has the power to steal from whom?” when we’re looking at this process.

I”ve been writing about the way different cultures not only ‘take’ dance steps or songs from other cultures or traditions, but also the way they then adapt these ‘found’ texts to suit their own cultural/social needs, values, etc.

I’ve argued all through my work that we can see the social heirarchy of the US in the reworking of dances and songs. What did they need to do to make these texts palatable for white audiences? With Tharpe it was ‘retuning’ her guitar and voice. With lindy hop, it was ‘desexualising’ and ‘tidying’ up the basic steps. Or at least presenting a different type of sexual performance.

Some interesting references

There’s a really great page discussing race records that includes audio files, images and written text here on the NPR site.

There’s also a pbs (US) site attached to the Ken Burns Jazz doco discussing race records.

For a (very nice) academic discussion, see David Suisman’s article called ‘Co-workers in the kingdom of culture: Black Swan Records and the political economy of African American music’ (The Journal of American History vol 90, no.4, March 2004, p 1295-1324) which discusses the ‘race records’ of the period and the racialised nature of the American recording industry.

You can also walk through this article via the JAH’s fantastic site (complete with images, sound files and other wonderful things). This is one site that really ROCKS.

Derek W. Vaillant has written a really interesting article about black radio in Chicago in the 20s and 30s which discusses these issues in greater detail (‘Sounds of Whiteness: Local radio, racial formation and public culture in Chicago 1921-1935’, American Quarterly vol 54 no. 1, March 2002 p25-66).

Katrina Hazzard Gordon has written quite a bit about African American dance culture. Here are a couple of references:

Hazzard-Gordon, Katrina. “African-American Vernacular Dance: Core Culture and Meaning Operatives.” Journal of Black Studies 15.4 (1985): 427-45.

—. Jookin’: The Rise of Social Dance Formations in African-American Culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990.

Read more about John Hammond, look at photos and listen to music here on this Jerry Jazz Musician page.

Wald, Gayle. “From Spirituals to Swing: Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Gospel Crossover” American Quarterly vol 55, no.3 (September 2003): 389-399.

thursday cat blogging

A little bit out of my sphere of interest, but it’s Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and that’s gotta be good.

I should really be putting this post under jeeeezus as well, as Tharpe is one of those big voice chicks who got it going on in revivalist shows originally.

Dancers know her for the stuff she did with Lucky Millinder (especially ‘Shout Sister Shout’), but she had a big rep as a stage performer.

I think I remember reading somewhere about her having to retune her guitar for white audiences in the north – apparently the distinctive southern tuning she used didn’t go down so well with the honkies. But this is a nice clip because it’s not all that often we see a black woman with a jazz/blues rep playing guitar on stage… Yes, yes, I know this is a 60s clip, and she’s playing gospel, but you know what I mean.

…I’m listening to a version of this song by Mahalia Jackson as I type… these chicks had freakin’ BIG voices.

when the metal is hot and the engine is hungry

Bunk Johnson’s Bunk and the New Orleans Revival 1942-1947

Bunk and the New Orleans Revival 1942-1947. Not something you’d like if Sidney Bechet gives you the shits. I’m not really the hugest fan of revivalist stuff any more. I did go through a massive phase, but I’m kind of coming out the other side… I mean, I like it, but I have limited tolerance for it. It can go badly when DJing, and I know I’ve had moments when I’ve really not liked dancing to it. I think you have to pick your songs and artists carefully, otherwise it can just be a bit too annoying.

Bunk and the New Orleans Revival 1942-1947. Not something you’d like if Sidney Bechet gives you the shits. I’m not really the hugest fan of revivalist stuff any more. I did go through a massive phase, but I’m kind of coming out the other side… I mean, I like it, but I have limited tolerance for it. It can go badly when DJing, and I know I’ve had moments when I’ve really not liked dancing to it. I think you have to pick your songs and artists carefully, otherwise it can just be a bit too annoying.

But this was an interesting CD (another from the Tasmanian jazz shop guy – gotta keep supporting him as they’ve just opened a JB in Hobart. Argh!), and I’m kind of interested in the parallels between the revivalists in Australia and the US. In fact, jazz in Australia is kind of interesting, when you consider the fact that there weren’t any African American artists in Australia to keep things fresh…. I’m sure you could make all sorts of provocative arguments about white Australian jazz… but I won’t.

The Jimmie Noone Collection

I’m especially liking The Jimmy Noone Collection from Collectors’ Classics.

I’m especially liking The Jimmy Noone Collection from Collectors’ Classics.

Favourite tracks? Very scratchy versions of familiar songs like:

After You’ve Gone by Jimmie Noone’s Apex Club Orchestra (1929)

Love Me or Leave Me by Jimmie Noone’s Apex Club Orchestra (1929)

My Melancholy Baby by Jimmie Noone’s Apex Club Orchestra (1929)

Ain’t Misbehaving’ by Jimmie Noone’s Apex Club Orchestra (1929)

And a few others, including

Wake Up! Chill’un, Wake Up! (as above)

My Daddy Rocks me (as above, with female vocals)

The vocals aren’t all ok for dancing – they can be a bit cheesy, but there are some goodies. Love Me or Leave Me is really fab. As is My Daddy Rocks Me. I’m not sure any of it’s really of a high enough quality for DJing, though it’s better than a lot of the really old recordings I have. Once you get into the 1920s, unless it’s a super Mosaic set, you really can’t be sure the quality will rock.

But I’m quite keen on Jimmie Noone atm. And Wingy Manone. It’s all pretty olden days, and not necessarily something I’d DJ for lindy hoppers, but it’s definitely stuff I like to listen to.

mahalia jackson live at new port

Talk about quick service – desires satisfied. I’m enjoying Mahalia Jackson Live at Newport.

want

- Any of these CDs from the Boilermaker Jazz Band.

- this CD from the Firecracker Jazz Band (listen – most especially to ‘Digga Digga Doo’ here)

And, because it’s not all want, I’m quite enjoying the Loose Marbles CD the lovely D sent me. Check out their version of ‘When I get low I get high’ (yes, a drug reference, yes one of the bestest songs evah). You can hear and watch them here, playing one of my favourite songs, ‘Four or Five Times’, heading towards the version I most prefer (a la the McKinney’s Cotton Pickers). The lyrics?

Four or Five times – McKinney’s Cotton Pickers, 1928

[scat]

I’m never about,

??

Just keep a-strolling,

Keep the ball a-rolling,

This isn’t a boast

But what i like most

Is to have someone true

Who will love me too,

four or five times.

Four or five times

Four or five times

there is delight in doing things right

four or five times

[four or five times]

Maybe I’ll sigh,

Maybe I’ll cry,

And if I die,

I’m gonna try…

four or five times.

We like to play

We like to sing

We like to go scedadilah do

Four or five times.

Bibop one

Bibop two

bibop three

Didahdiladee

Four or five times

[scat]

Yes, sure, ok!

What?

Yes. ! !

Four or five times,

Four or five times,

There is delight,

In doing things right,

Four or five times.

There’s a bunch of scatting in there I couldn’t transcribe, but you get the point.

Oh, and yes, it’s all about double entendre, yet again.

I love this song a whole lot, especially this version, though I never get to play it (too old, too fast, to obscure for mainstream lindy hoppers). I do play a pretty fabulous 1930s version by Woody Herman and his Orchestra which always really rocks the dancers. It’s a lot straighter and safer and very lindy hoppable, but still lots of fun.

There’s a version by Jimmie Lunceford (c 1935) which gets a fair bit of play in Melbourne, and I do prefer it, musically, though it’s lower energy than the Herman version. I play the Herman far more often than the Lunceford version. I also have a fully sick version by Lionel Hampton, which I never seem to play. I have no idea why not – it’s freakin’ awesome.

monday jazzblogging (because everyday’s caturday when you likes jass)

I wish I could shimmy like my sister Kate ~ Mugsy Spanier and His Ragtime Band 1939

Oh, wish I could shimmy,

like my sister Kate,

Now she shakes it like jelly,

On a plate.

My momma wanted,

To know last night,

Why the boys think Kate’s so nice,

Every boy in my neighbourhood

Now knew she could shimmy

And it’s understood,

I might be late,

But I’ll be up to date,

When I can shimmy like my sister Kate

I’m shoutin’

shimmy like my sister Kate,

Oh boy.

Just one verse, really, but it’s worth it, just for that line – she shakes it like jelly, on a plate. I like that sort of talk.

And the saucy trumpet (or is it a cornet?) solo makes it all work. But really, we’re all just waiting for the big old shouting chorus at the end.

(That’s not Kid’s Ragtime Band there in the image, it’s his other band – the Original Creole Jazz Band).

[PS – I just found this ‘collection of New Orleans greats by Mahalia Jackson’ and nearly weed with excitement. Apparently it’s a misprint. Wracked with disappointment. Trying to get over it]

[PPS my favourite Kid Ory song is ‘Creole Bo Bo’ – a French nursery rhyme done with a seriously swinging New Orleans rhythm which makes me HAPPY! It also defies DJing. At 203bpm, with French lyrics, an obviously nursery rhyme melody and too much swing for charleston, it’s just not a song you’ll play every day. For anyone other than yourself.]