Nathan Sentance’s piece Diversity means Disruption (November 28, 2018) is important. It addresses the experiences of people of colour (specifically first nations people) within arts and information institutions – libraries, museums, galleries. My own background is in universities and libraries, with my information management postgrad work focussing on the management of first nations’ collections and access to collections.

In this piece Sentance makes it clear that diversity in itself is not useful. Just having people of colour on the team does not provoke institutional change. Representation is not enough; we need structural, institutional change to disrupt the flow of power and privilege.

In this post I’ve taken some lines from Sentance’s article (in green italics), and I’ve responded to them with specific reference to the lindy hop and swing dance world.

Why a diverse teaching line up will change the culture of lindy hop. And a lot of white people will find that uncomfortable.

Or

Having black women teach at your event is radical.

Why hire First Nations people into your mostly white structure and expect/want/demand everything to remain basically the same?

Why hire people of colour to teach at your dance event within your mostly white structure and expect/want/demand everything to remain basically the same?

Why don’t libraries, archives and museums challenge whiteness more?

Why don’t dance events and dance classes challenge white, middle class modes of learning and learning spaces more?

As result of the invisibility of whiteness, diversity initiatives are often about including diverse bodies into the mainstream without critically examining what that mainstream is

As a result of the invisibility of whiteness within lindy hop, diversity initiatives are often about just hiring black teachers at big events, without critically examining the way the classes and performances at these events construct a white ‘norm’ that reinforces the mainstream.

Kyra describes this “When we talk about diversity and inclusion, we necessarily position marginalized groups as naturally needing to assimilate into dominant ones, rather than to undermine said structures of domination”

White lindy hoppers ask ‘why aren’t there any black dancers in my local lindy hop scene?

I have seen a high turnover of staff from marginalized communities, especially First Nations people, as well as general feelings of disenfranchisement.

Black dancers get tired of being the only person of colour, asked to ‘give [themselves, their time, their energy] a talk about black dance and black culture’ to white audiences, to give, to work, to be visible, to represent blackness. Tokenism is tiring. Tiring.

1.Don’t let white fragility get in the way of change.

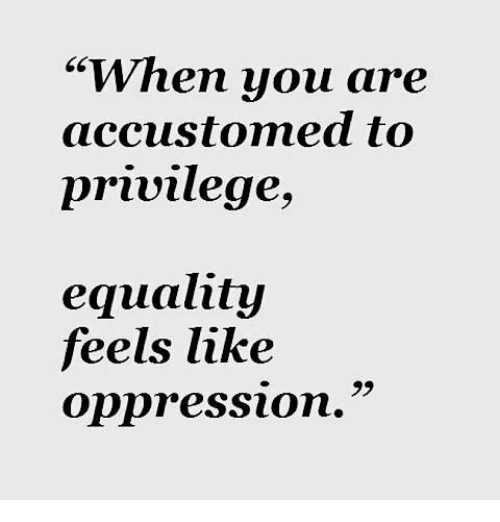

….[white people] need to understand that [their] discomfort is temporary, oppression is not and as organisations we need to create more accountability.

It is difficult to be told you are racist, when you are pretty sure you aren’t. It’s difficult to be criticised, as a dancer, as a person, by someone you feel you are including as a charitable act of ‘diversity’.

Ruby Hamad wrote about this and how the legitimate grievances of brown and black women were instead flipped into narratives of white women getting attacked which helped white people avoid accountability and also makes people of color seem unreasonable and aggressive.

If you feel attacked, perhaps it is only that you are being disagreed with?

3. Support us.

…Being First Nations person in a majority white organisation means a lot is asked of you that is not in your role description. This needs to be acknowledged.

Being a black teacher at a majority white events means a lot is asked of you that is not in your role description. This needs to be acknowledged.

Your extensive planning and carefully structured workshop weekend might seem very good and progressive to you. But it might be alienating, discomforting, and marginalising for people of colour. You might feel your black guests are ‘helping white people learn’, but they may feel set up as a ‘great black hope’ on an inaccessible stage. When what they might prefer is to spend time with other dancers as a new friend, as a peer, and to teach using other models.

If all you’ve changed in your program is the colour of the skin of the people presenting, then you haven’t changed anywhere near enough.

Additionally, support should include providing First Nations only spaces when necessary as well as supporting staff with time and resources to connect with other First Nations staff in other organisations and to connect with different community members as part of our professional development.

Support should include providing black teachers and performers with black only spaces. …and the time and resources to connect with other black teachers and performers.

Hire more than one black person at a time.

Give black women time with other black women; ‘black girl talk’ is important.

Hire black dancers from different styles, black singers and musicians, black artists and writers, and give them time to talk and make friends.

4. Remember it ain’t 9-5 for us

Dance teachers at events are ‘on’ all the time they are in front of other people. Black dancers are black all the time. Their experiences of race shape their whole lives.

Black dancers often consider themselves part of a bigger black community, to whom they owe loyalty and responsibilities. They don’t owe you a complete and full history of everything black about lindy hop. Some things are private, and some things should remain secret. They don’t owe you all their time and energy to ‘help white people learn’. They have and need time in their own communities and families.

A useful analogy:

The Savoy ballroom was an integrated space. That means that white people had access to black spaces*.

Some spaces need to remain black spaces, where white people cannot go.

Some dance history and dance knowledge needs to remain black culture; white people aren’t owed all of black dance.

This is what it means to decolonise black dance: to take back physical and cultural space. To say “No” to white bodies and voices. And for white people to accept that.

Nevertheless we cannot have change or meaningful diversity without disruption.

Having a black teacher at your event will not change the status quo.

You will need to change the way you structure your event. The way you speak. The pictures you show. The language you use.

Having a nursing mother teach at your event will not change the status quo.

You will need to change the way you structure your event. The clothes they wear. The way you speak. The start and finish times of your classes. Their bed times.

Representation is not just about black bodies or female bodies being present. It is about disrupting the status quo – making structural change – to accommodate change.

To have more women teach at big events, to have black women teach at events mean something, you will need to change the way you run events. You cannot simply slot a black or female body into a space a built for a white man and expect to change your culture. You will need to change that space completely.

A lot of your usual (white) students and attendees will feel uncomfortable with a space that privileges black culture and black people. This won’t make these students and attendees happy. They may not have a ‘nice’ time. They may find classes challenging or upsetting. They may not like the way black teachers talk to them, or that they don’t have 24/7 access to black teachers’ time and energy. They may be angry that their previous knowledge and skills weren’t valued as highly as other (black cultural) skills and knowledge are at this event.

This will be difficult for many white organisers to deal with, both in the moment, and in feedback after the event.

Are you prepared to deal with that?

No?

Then it is time you started taking classes with teachers who ask you to learn in new ways. It is time for you to humble yourself. To do things that are difficult and confronting. To be ok with feeling uncomfortable. Practice. Because you need to be ok with this. You are going to have to give up ownership of some of your most valued possessions.

Lindy hop wasn’t dead, white people. It wasn’t dead and waiting for you to revive it. It was alive, it was in the bodies and music and dance of a nation of black people. Modern lindy hop culture is marked by white culture and race, by class and power.

This is why black lindy hop matters.

*Marie N’diaye, LaTasha Barnes, and I were in conversation one night at a bar. Marie made this point. It made a profound impact on me, to have a black woman say this to me, at a white-dominated event that purported to be all about African American vernacular dance. “The Savoy ballroom was an integrated space. That means that white people had access to black spaces.”

It made me realise: I do not deserve or am owed access to all black dance spaces and culture. I do not have a right to learn all the black dances, to acquire all the black cultural knowledge. It is not mine. And it is important for me to remember that a desegregated Savoy in the 1930s gave white people an even greater degree of access to and ownership of black culture and black bodies in motion. A key part of decolonising lindy hop, is for me – a white woman – sit down, and accept that I don’t get everything I want. And in that particular moment, I needed to know when to get up and leave the conversation.

Because black girl talk is important. Black vernacular is important. And I shouldn’t assume I have an automatic right to participate in it, even if it’s happening in desegregated places.

This is made explicit in Kyra’s post, How to Uphold White Supremacy by Focusing on Diversity and Inclusion:

Closed spaces for marginalized identities are essential, especially ones for multiply marginalized identities, as we know from intersectionality (not to be confused with the idea that all oppression is interconnected, as many white women who have appropriated the term as self-proclaimed “intersectional feminists” seem to understand it). Any group, whether organized around a shared marginalized identity or not, will by-default be centered around the most powerful within that group. For example, cisgender white women will dominate women’s groups that aren’t run by or consciously centering trans women and women of color. A requirement for all groups to be fully open and inclusive invites the derailment and silencing of marginalized voices already pervasive in public spaces, preventing alternative spaces of relative safety from that to form. Hegemony trickles down through layers of identity, but liberation surges upwards from those who experience the most compounded layers of oppression.