God I write long posts. I just sit down, write ’em, then give them a quick edit. Sorry about that. It’s how I wrote my thesis. But with my thesis, I edited the thing. I don’t edit blog posts because WHO CARES. So, brace for impact, yo.

Some friends of mine have started getting together to practice solo dance. This isn’t unusual. A very large slice of my dancing friends are working on solo dance at the moment. You know why: you don’t need to find a partner, you can practice on your own, solo dance is an excellent way to improve your dancing across the board… and so on. I see quite a lot of groups of people getting together in their own time to do some of this work. The groups change and rarely last in exactly the same combination of people for more than one or two sessions. The point is not to forge a single ‘practice group’, but for a group of friends to get together on a particular day to work on something in particular, at that moment. This mutability is partly what makes the process so powerful: the structure survives as long as it is useful, and then it changes to meet its participants needs. Or it quietly fades away.

I think this self-directed learning is a very good thing. And I think, in my city, at this moment, these sorts of casual (yet quite focussed and determined) temporary creative sessions are the product of a scene which lost direction there for a minute. We didn’t have any higher level dance classes, and dancers really felt the classes they were going to weren’t focussed enough, the content wasn’t what they wanted to work on. So they made their own. I think that if our dancers’ needs had been met by classes and workshops and formal organisations, they wouldn’t have developed solutions on their own, and we would be the poorer for it.

Again, I have to say that I think this is a very, very good thing. Planning our classes for the new year (which include a new more challenging class), I was absolutely determined not to try to replace or conflict or compete with those independent projects. We really need that self-directed learning, and that sort of innovative, independent response to a challenge is a sign of a healthy community. I’m making this point because I know some teachers in some scenes perceive other classes and other learning spaces as threats, as though dancers working outside their influence were challenging their own authority or value and status as teachers and dancers. Me, I find these sorts of projects inspiring. And they remind me that I have to keep working on my own dancing and teaching if I’m going to keep up. I also think that I need to keep tinkering with my class formats if I’m to stay relevant to my students. More simply: someone else being super awesome doesn’t make you less awesome. It should inspire you to become as awesome as you can be.

So now, let me just sketch out the learning spaces in my city’s dance scene. Firstly, we have formal, weekly classes run by dance schools. Schools dominate almost every learning space in Australian lindy hop. Institutions: we have them. There are good and bad things about this. Then we have formal workshop weekends run by those schools, and featuring visiting international and occasionally interstate teachers. We also have the occasional workshop taught by visiting teachers and run by dancers in our scene. These workshops have lots in common with weekly classes: clear hierarchies of knowledge (oh boy, do lindy hoppers luuurve clear hierarchies); formal start and finish times and dates; fixed prices.

Then we have private classes, where local and visiting teachers work with dancers individually, for a much higher price than regular classes or even workshops.

We also have troupe training sessions, where members of a troupe get together to work on routines or skills. These troupes are managed schools or individuals, and are gated: they are closed to anyone not in that troupe, and troupe membership is also gated.

And then (most relevantly for this post) we have informal practice sessions run by individuals, couples or small groups to work on their own dancing. They might be working on competition material, performances, or just getting together to explore ideas or cement material from a class. This last style is the most informal, but it still requires some organisation: studios need to be booked, times need to be set, participants need to be contacted. And then the sessions themselves need to be organised, if the group is planning to work on a single project in the session.

As you can see, these practice sessions are great for developing dance skills, but they are also GREAT for developing organisational skills, professional and personal networks, and for inspiring self-reliance and creative, personalised solutions to problems. They can also be great for teaching dancers how to deal with conflict and ‘failure’. Sometimes private sessions explode in interpersonal conflict or incompetency. Learning to come back from a heinous mess is a real craft. But knowing how to prevent them is even better.

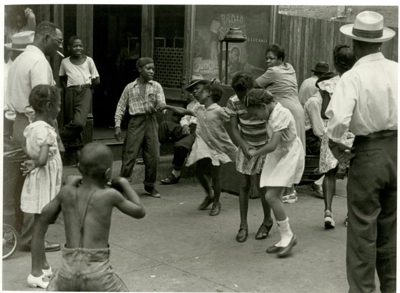

The social dance floor is another important learning space. The social dance floor allows for the informal, ‘casual’ transmission of moves between friends and dance partners. And there’s less talking, more dancing, which is solid gold for learning dance skills. When we have a large number of follows without partners (and these are always all women), we also see these groups of women getting together on the social floor to play with moves or share ideas or practice.

I want to distinguish between this type of dancing on the social floor and ‘solo dance’ on the social floor, where people move out into the dance floor to dance. In contrast, those groups on the side of the dance floor usually involve women who are open to being interrupted, whether by dance invitations or other things.

Right here I have to note: if you’re asking yourself ‘how do I tell the difference, when I want to ask someone to dance and I’m not sure whether they’d welcome the interruption?’ you need to open your eyes. If you spend a bit of time watching and learning, you’ll figure out the difference. And, of course, the most sensible solution is to wait til the end of the song, then ask the person you have your eye on: “Would you like to dance with me, or are you rocking the solo stuff instead?” If someone asks you to dance with them, and you don’t want to, it’s totally ok to say “Hey, thanks for asking, but I’m rocking this solo stuff instead.” Or even “Thanks for asking, but not right now!” That’s right, friends, it really is that simple.*

All of these learning spaces exist in a complex web of relationships and interactions. Most people are participating in more than one of these at a time, and their engagement with a single space ebbs and flows and their needs change. So, for example, I was part of a small group of women that got together to learn a solo routine, and then performed it last year at a large dance. We got together a few more times after that to work on things, but we didn’t perform together again. But that period of working and performing together galvanised our interests, and I think was an important precursor for the weekly solo class two of us teach, and for the competition entry two others put together this year. It certainly helped us develop skills (performance, choreography, practice session management, communicating ideas, developing professional relationships) and raised our profile as solo dancers. For other dancers outside the group it put solo dance into a public forum. Got it on the radar, so to speak.

The point here, is that these learning spaces and networks change. They’re not preserved for their own sake; they have to have function and use-value. Much like the dances we do, really. If they don’t have value and functional appeal, we don’t get into them. Until they do meet our needs and appeal to us.

[Digression]

This factor proves most difficult for institutions, which aren’t always so good at accommodating or enacting change. I think that a dance school (which runs social events, workshop weekends, provides professional networks, stimulates economic development and teaches dance) needs to be agile in its practices. It needs to be able to change.

This means that class curricula need to be adapted and developed to respond to local scene fads, interests and needs. Teachers need to be continually updating and refining their teaching skills. Economic and promotional strategies need to respond to the broader economic climate. And I think a dance school’s brand needs to be resilient and to slowly change in order to expand or focus the market. All this is really quite challenging for most dance schools, mostly because they’re run by people who are dancers first and business people second. It also takes a heap of thinking and planning and some pretty serious resources. And, most importantly, I’d argue, it demands teachers and administrators stay in close contact with the needs and interests of the dancers in the scene. Running surveys doesn’t cut it. You’ve got to be out there on the social dance floor, at competitions and performances, out at dinner and generally keeping in contact with people. And it can’t just be one person all this, as that one person’s experiences will shape their perceptions of the community. It needs to be a network of different types of people. Argh! The work! And yet – the opportunities!

[/]

Rightio, now we have an idea of (some of) the learning landscape of my city’s dance scene. There are plenty more gradations and variations, but these are the ones I want to touch on. And, of course, the ones I see and am aware of. I’m sure there are plenty more I haven’t thought of, or just don’t see, because I’m not moving in the right social circles. Dang it.

Here’s where I get to the point of this post. I have a group of male friends who are involved in what they call ‘man troupe’. The name is really a bit of a joke, but the idea is pretty cool. Male friends get together to work on dance, and women aren’t allowed. Though the ‘rule’ is that a woman can come, if she brings four men with her. Of course, occasionally a woman will go along. But seeing as how those same men are also involved in other casual practice sessions that do include women, you could argue that the difference between ‘man troupe’ and other sessions is just who turns up.

But a friend made a really interesting point the other night: man troupe is about encouraging men to do solo dance, and more importantly, to get their own skills up to the level of the women dancers in our scene. This point was made in conversation, by a couple of men involved with the group, and I realised that the goal wasn’t necessarily competition with women dancers or excluding women dancers. The goal really was to work on their own dancing, in a space where the participants have similar goals and ideas about dancing, can support and encourage each other, and push themselves and their dancing to ‘keep up’ with other dancers in our scene. Which is of course the reasoning behind most informal dance practices.

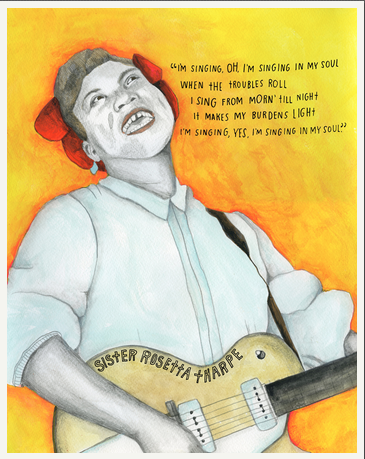

But these guys also made the point that most of the solo dancing in our scene (and in many other scenes, I’d argue), is taught and danced by women. This is true. My (female) teaching partner and I teach solo dance weekly. Previous local solo workshops have been taught by women. Even our visiting teachers teaching solo workshops have been mostly women. And when we look onto the social dance floor, there are more women than men solo dancing.

This, of course, fascinates me. Women tend to gravitate to solo dancing because they’re waiting on the side of dance floor for a partner, because their scene has too few leads. It’s also quite common for a lindy hop class to default to a ‘solo class’ if there are far too few leads in the class. And then, in a more general sense, women in our culture (the mainstream, predominantly Anglo urban Australian culture), women tend to dance more, and with a greater range of moves and steps, than men. I’ve written about the discursive and social power of women solo dancing plenty of times before, so I don’t need to go into this again. But all this means that women are more likely to be exposed to, and to take part in, solo dancing.

[Digression]

The gendering of this is a direct result of the way we gender leading and following. In the small block of more advanced classes this month we built solo work’ into our classes: students had to dance the basic rhythm on their own over and over. If they were standing out in the rotation because they didn’t have a partner, they had to dance through the rhythm and work on the material anyway. If they found something getting messy with their partner, they were encouraged to stop and do it on their own for a second.

I was really surprised to see just how frightening many of the leads found this. So confronted that a handful simply couldn’t do it. They just felt too self-conscious. And some simply couldn’t stay focussed, because they weren’t used to having to work on their own dancing in the focussed way that solo dance requires. They were simply too used to the familiarity and crutch of another partner.

This worried me a bit: I see this as a serious problem in our dance community. It’s bad news for gender politics (men and women can’t function independently), and for the standard of dancing in our scene (we have to be able to dance alone if we want to dance together). More specifically, it was made very clear that many of the men in the room were seriously disadvantaged by some of the prevalent teaching practices in our scene. This silly heteronormative, conventionally gendered partnership model is bad news for men and women. And their dancing.

[/]

I think the theme of this post today was crystallised by blue milk’s post ‘Boys and masculinity in young adult fiction’. There, the discussion centred on the importance of positive role models for boys in fiction. Or, to make my thinking clear, in creative practice. There’s also been some talk about the national HSC results this year, where girls topped maths and sciences for the first time. A fair proportion of the media coverage saw this as a dire tragedy, a sign of the hopeless feminisation of education and Decline Of Man. More sensible observers pointed out that boys were still over-represented in maths and sciences, and that perhaps the problem is not perceived declines in results, but in the pedagogic practices at work in our communities.

What’s this got to do with dance? Dancers need inspiration (things to aim for) and role models (who demonstrate how to do and be something). Dancers need a range of learning spaces to achieve a range of learning goals.

I’ve been quite concerned about male solo dancing role models in my scene for a while. I deliberately chose a young, athletic, ‘cool’, highly skilled male teacher for a workshop weekend a few months ago, because I wanted to provide a positive role model for the male dancers in our scene. I wanted our local male dancers to see just how cool solo dancing can be for men. I also wanted to them to see how this solo dancing informs a male lindy hopper’s dancing. And I wanted female dancers to see how this then improved their dancing experiences. And most importantly, I wanted dancers of both sexes to see how good dancing partnerships require two happy, healthy and enthusiastic partners.

Sure, I had some ideological goals (deconstructing patriarchy is important for men as well as women), but I also had some fairly mercenary ones as well. Our solo class has solid numbers, but we don’t see many men there. Probably because both of teaching are women. And because the class is dominated by women, and many men find an all-women class quite intimidating. In more general terms, I wanted to provoke our male dancers into critiquing their own dancing, and realising they can’t just rely on being one of a small group of male leads to assure their status. I wanted them to realise that if women dancers discover that solo dancing or leading is more fun than following complacent leads, they’ll do those things instead. And this would shake up the power dynamics in the scene. ‘Orsm’ is determined by dancing skills and funfactor rather than the possession of a dick.

This last point is a tricky one, because I don’t think the way to social change is through tearing people down. I think that feminism is about making things better for all of us, men and women. I didn’t want our male dancers to get down on themselves. I wanted them to feel so inspired by what they saw they decided they had to challenge themselves to become even more awesome.

I’m also very, very sure that to achieve broader cultural change within a community (ie to undo rubbish gender shit, to revitalise a scene, and to encourage exciting creative work), we need diversity in cultural practice. Lots of people have to be working in lots of different ways. And that they shouldn’t all be agreeing with each other. We need (friendly) conflict, critical engagement and even competition (physical as well as ideological) as well concerted effort to provoke people’s efforts.

I also think that this work has to be happening in different spaces and discourses. It has to be both self-directed, independent, tactical (in de Certeau’s sense) and institutional or strategic. I know we’re supposed to be sceptical of institutions in socialist feminist discourse, but I’m also a pragmatist. Institutions, with their centralised discourse, are very powerful tools for communicating ideas and initiating change.

[Digression]

Lots of people have asked me why I began teaching with a big dance school, particularly a school with a less than savory reputation. And my answer is that I’ve done all that independent, non-profit work in volunteer committees, and they’re sure as fuck not bastions of egalitarianism and equality. I also felt that I could be more productive and do what I need to do with the resources of a well-organised, fairly formally structured group. I’m also a bit tired of working for free. Dance projects need to be socially sustainable, but being socially sustainable also means be financially sustainable. Losing money or having no money is stressful, and a stressed out worker eventually gives up. I’m also fairly impatient with the bullshit idea that people should work for free in dance scenes ‘for the good of the community’ or as an act of historical preservation. Fuck that shit. Those exploited workers are the community, goddamnit.

[/]

Finally, my feeling is, as always, that if something shits you, you have a few options: bitch about it, then get over it; bitch about it, then walk away; bitch about it, then DO SOMETHING ABOUT IT. That last one is usually the option I take. I don’t have a lot of patience for dancers who complain and complain and complain about the terrible DJing, the lack of quality classes, the awful social dances, the terrible pay rates, etcetera, etcetera and then DON’T do anything about it. If we all just bitch and bitch and then just stew in our own shittiness, we’ll just get miserable and useless. For women dealing with bullshit gender politics, if we concentrate on bitching about things and then don’t follow up with action, we are participating in our own disempowerment.

What do I mean by ‘do something’? I don’t mean that you then have to go out and run your own dance events to fix the problem. Most of us don’t have the resources to do that. There are plenty of other, more achievable and more satisfying ways to be a power for good in your local community. I’ve found that it’s far more productive to back up all my rants about gender politics in the dance scene by learning to lead and then getting out there and leading. Every time people see me – a woman! – leading, I change things. Particularly if I’m having fun and it shows. It’s even easier for me to back up my opinions by encouraging other people who’re doing interesting things.

Don’t like the music? Learn to DJ. Tired of DJed music at dances? Find good bands, then tell people about them, take your friends to see and dance to them. Shitty about that lead who continually throws new women dancers into the air? Call him on his bullshit! Or, much more usefully (because those fuckwits never get the message), get in there and dance with those women dancers yourself! That way they’re less likely to tolerate fucked up bullshit from those leads that hurts and frightens and embarrasses them. And those idiot fuckwit leads will see some good role modeling and won’t have a chance to exploit their position as ‘an accessible lead’ with awful behaviour.

One of my favourite – and perhaps the most powerful – forces for change in a dance scene is the social lubricant. Walking up to people and saying ‘hi’, asking your students to dance, organising pre-dancing dinners, inviting people to work on dance stuff with you, thanking the band at the end of their set, sending a quick email to tell an organiser you loved their work, responding to general email requests for help (even if you just say ‘sorry but I can’t’), throwing yourself into a competition, planning a performance…. all that stuff is super powerful. It’s the sort of tactical, on-the-ground, grassroots force for change that really makes a difference.

And do things like man troupe. Man troupe is an exciting, practical tactic for enacting social and cultural change.

To sum all this up, then…

I think dance communities need diversity to be truly creative and dynamic. If there’s one thing evolutionary theory can teach us, its that robust communities require randomness (the mutation that provides that characteristic that helps us survive environmental change) and ‘genetic’ diversity. If we all look and think and dance the same, we’re not creative. We should all just give up and go do aerobics.

Someone else’s success does not diminish your own. Just because person X is a brilliant dancer, don’t mean that you’re less a dancer. Stop comparing yourself to other people and start celebrating other people’s successes. Take their achievement as inspiration and motivation. Work to achieve good outcomes for everyone.

Try something yourself, rather than waiting for a solution to be sold to you. This is where capitalism in dance sucks arse. You don’t need to wait for your teacher/school to give/sell you a solution to your problems. You can totally fix this yourself. Complain and bitch if you’re cranky, but then step up and get shit done yourself.

One of my favourite things about the international lindy hop scene is that learning is absolutely central. Whether you’re doing classes or figuring out how your body works.

Learning: it’s good. As we say in my house, “Don’t deny knowledge!”

*I don’t like to sexualise partner dancing, but there are parallels between sexual consent and asking someone to dance respectfully, and than accepting a polite ‘no thankyou’ gracefully. If we condition women in our scene to never say no, and we condition men in our scene to assume a woman will never say no, we’re setting up some pretty horrible power dynamics.

Basically, expecting someone to just say yes to your dance invite, whether they want to dance with you or not, is a lack of respect for that person. You don’t respect their right to make decisions about their own body. In our culture, this is gendered. Women are expected to be grateful for a man’s attention. We’re expected to drop everything when a man asks us to dance, and be grateful for the attention. Men are encouraged to assume a woman will say yes to a dance invite, even if they don’t want to dance with them. This is why I hate the ‘never say no to a dance invite’ bullshit that circulates in the lindy hop world. Damn right you can say no! And you know what? Some people just don’t want to dance with you, and you need to respect that. But you have to keep asking. Because being asked to dance is really good for the ego. As blue milk writes asking for consent is sexy. And while people say no sometimes, they also say YES sometimes.

This is also why I’m a big fan of solo dance, women learning to lead, and women being exposed to respectful, talented male dancers. Women need to know that the most important thing in lindy hop is not dancing with a man/leads. The most important thing in lindy hop is fun and pleasure and creativity and all that wonderful stuff. And all this is why I goddamn hate that mime-invitation-to-dance. USE YOUR WORDS, DAMMIT!

(Unless you don’t speak the local language or you’re asking someone to dance and don’t speak their language. Then it’s ok.)