(image: “Ultracrepidarian: A person who gives opinions and advice on matters outside of one’s knowledge” from The Project Twins’ A-Z of Unusual Words)

I reckon this post about dancesplaining is good stuff. I like the way Jason expands the idea of mansplaining. Mansplaining is about power, and dancesplaining is about power. I like the way Jason has expanded the idea of explaining-as-power. He’s making the point that this act of power isn’t about biological sex, it’s about social power. This seems to be something that a bunch of commentary on sex and gender in dance getting about at the moment doesn’t seem to grasp.

In other words, while we might associate particular characteristics or qualities with masculinity or femininity (eg violence or aggression or technical know-how might be associated with masculinity in anglo-celtic discourse), they aren’t actually biologically determined. Men aren’t naturally aggressive or violent or good with tools (lol) because they have a bunch of testosterone or a dick or a brain wired in a certain way. Men often demonstrate violence or aggression or are the first to have a go with a tool because the society they grew up in encouraged them to be that way.

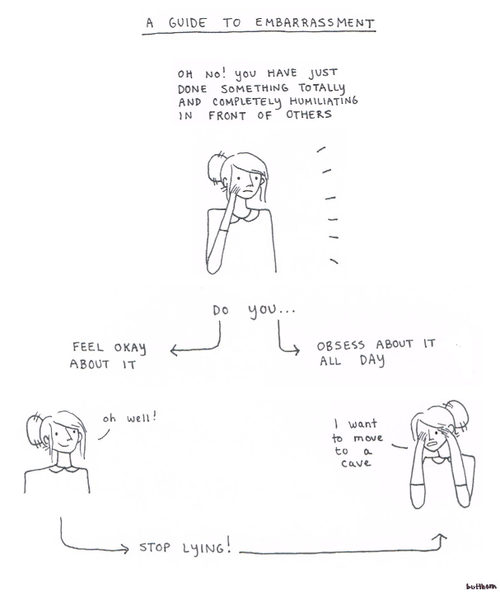

So mansplaining isn’t biologically determined, it’s an act of power, where the person explaining assumes they know more, and assume they have the right to speak/explain. When this explaining person is a man, explaining something to a woman, they’re often taking advantage of the fact that women in this same cultural context are brought up to be ‘polite’ and to avoid confrontation. That means avoiding interruption or telling an explainer that they already know this stuff. Avoiding conflict can also be about helping other people save face (and avoid embarrassment or loss of face/status). Many women help men save face to avoid conflict because in their experience conflict can often involve physical conflict: an angry, embarrassed man can be a violent man.

Danceplaining and mansplaining isn’t often malicious or deliberately dictatorial. It’s usually an unconscious demonstration of discursive power. Just as a man mightn’t stop to worry about whether that guy who just got on the train is about to sit next to them and make suggestive comments, a man who explains mightn’t stop to think about whether he should shoosh. In both examples, men have lived with the experience and idea that they will be safe on public transport, that they won’t be harassed, and that it’s ok to explore or explain their thinking out loud. Both of these public behaviours are about status, power and confidence in public space. They’re both also about the power of feeling safe enough to explore a new idea in front of other people.

If you want to have a bit of a read about the ‘mansplain’ concept, I suggest starting with Rebecca Solnit’s piece ‘Men Explain Things to Me: Facts Didn’t Get in Their Way’.

I like Jason’s piece because makes it clear that explaining – dancesplaining – isn’t necessarily about gender. While men might do it it women a lot in class, women quite often return the favour and explain to men why they’re doing things wrong. But I do think it’s about power, and I’d argue that certain types of power can be gendered (or associated with a particular gender identity) in certain contexts. So dancesplaining is often perpetrated more by men, and as most dance classes have more men leading than women, we see more leads/men dancesplaining to follows/women than vice versa. I’d probably add that a male lead teacher should be particularly careful not to paraphrase and repeat a point his female follow teaching partner has just made in class settings. That’s a type of mansplaining too.

Jason extends this thinking to explore how this type of behaviour in class affects the way we might think about leading and following generally.

I’d argue that dancesplaining (as a gendered behaviour) works with other gendered behaviour to create a continuum of gender and patriarchy. This is how discourse and ideology work: if it was just one little thing that bothered us (and we could fix with a quick solution), then feminism would be redundant within a couple of hours. But patriarchy is complicated. This is why I have troubles with the recent posts about ‘sexism’ on Dance World Takeover: the thinking is too simple, and the solutions are too simple. A reshuffling of ideas about connection isn’t going to magically solve sexism in a community. It might be one point at which we can engage with particular ideas about gender and power, but tackling that one thing this time will not quickly or easily ‘solve’ patriarchy.

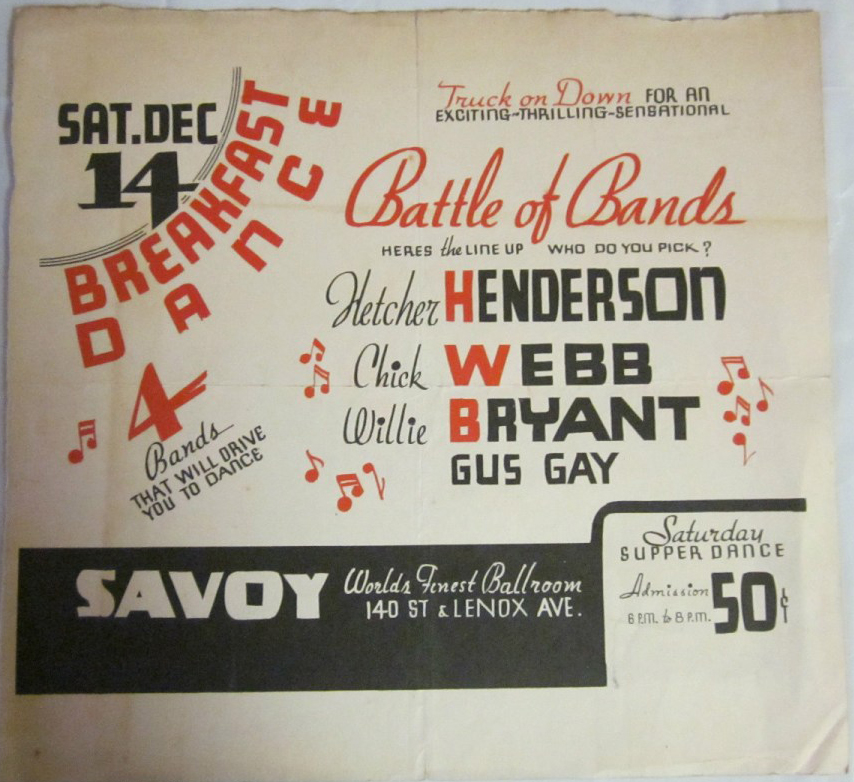

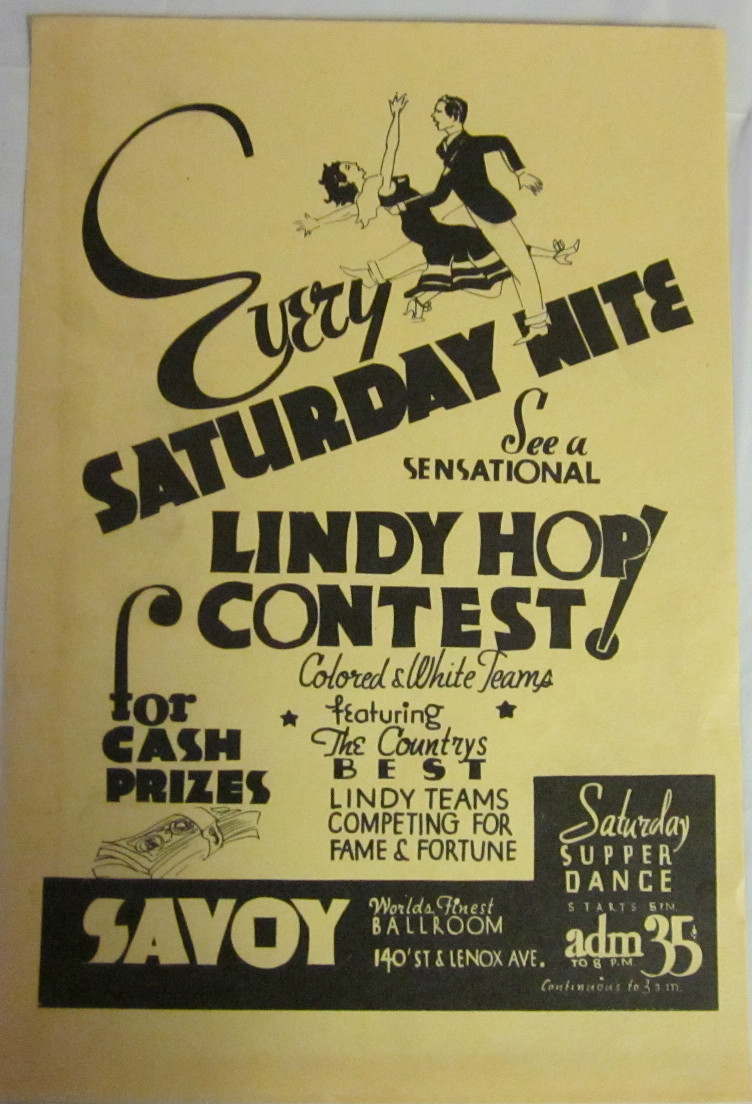

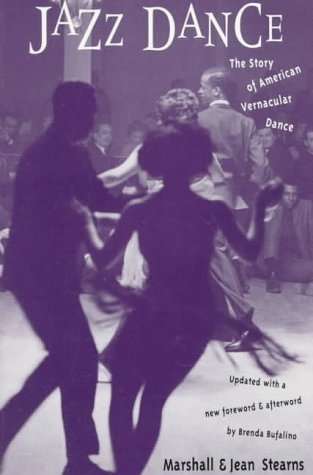

If we are to engage with gender in the lindy hop world in a constructive way, we need to think about all sorts of stuff: clothes, notions of ‘beauty’ and ‘strength’, discussions about food and ‘health’, teaching practices, competition formats (eg how is a jack and jill competition judged, and how does this process articulate ideas about gender?), the role of solo dance, the place of aerials, how we manage and think about injuries and pain, ethnicity and race and how we think and talk about it in dance, talk about sex and sexuality in dance partnerships, labour relations and the role of ‘volunteers’ and unpaid labour, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera. Gender: it’s complicated.

This is why, though, I’m quite pleased by Jason’s piece. He takes one behaviour (or use of language and power), and then draws out the effects and related behaviours and thinking within a culture (and cultural practice). I’m especially delighted by the way he presents his own thinking and behaviour. This really is what I would call being a feminist ally. Doing feminist work. I am also very pleased by the way this thinking makes clear that feminist work can also be socialist work, and also be the work of pacifists and human rights activists. Feminism might be centred on gender, but we can’t talk about gender without also talking about economics, ethnicity, sexuality, violence, and so on.

I was especially delighted by this paragraph in the ‘establish permission’ section:

Both as a teacher and as a student, I have found it is often really helpful to approach first with a question along the lines of “Can I make a suggestion?” If he or she says “yes,” then we can proceed to having a discussion about it. If he or she says “no,” then I keep my opinion to myself unless that person is causing serious harm (in which case I might have led with something more direct like “I need to talk to you”). The act of asking for permission can feel a tad cumbersome but it respects the other person’s boundaries and gives them a moment to adjust to a state of readiness to hear feedback. It is the dance class equivalent of inviting someone to a performance evaluation rather than barging into their office and telling them they need to shape up or ship out.

I think this is a gorgeous illustration of how undoing the power dynamics (and hierarchies) of pedagogic discourse in dance can work to undo other dodgy power dynamics in a dance community. The class is, of course, where we socialise new dancers – where we teach them not only how to dance, but how to be in a dance community. It’s something I need to remind myself: though I might be a teacher, I don’t automatically have the right to correct someone’s dancing in class. And how I should correct them needs to be carefully thought about, to promote and encourage mutual respect.

If you’re curious, I’ve written other posts where I’m pretty much annotating the development of my ideas about teaching. I’m only new to teaching dance and boy am I making a lot of mistakes.

– Dealing with problem guys in dance classes: where I write a huge, long, rambly post exploring my ideas about this, and nut out some strategies.

– Self Directed Learning: where I look at alternatives to the formal dance class, and how this might destabilise hierarchies, and also complement traditional learning models.

– teaching challenges: routines, structure and improvisation in class: where I remind myself that rote-learning is about power and hierarchy, and not in the spirit of lindy hop.

– Teaching challenges 2: drilling and memorising: kind of like that previous post, but with some dodgy referencing of pedagogic lit.

– Valuing the process rather than the product: where I talk about a bunch of things, but most importantly, about the importance of being wrong and making mistakes.