Last night I was reminded that I haven’t been giving my ‘if you’re struggling, the basic things you should be looking for are…’ speech to the solo jazz class lately. It’s the speech where I point out the key parts of jazz dance: clapping, facing the right direction (occasionally), bouncing along to the beat, possibly shouting out at the best parts. It’s a joke speech (though I mean it completely), and I’ve noticed that after I give it, almost all the students suddenly work nine times harder. It’s as though permission to find this challenging suddenly convinces people they rock.

I gave the speech last night in class, and saw an immediate relaxing of a tension that I hadn’t even realised was there. It wasn’t that all the students were struggling and unhappy, but that suddenly we all remembered we had permission not to be perfect. PERMISSION to enjoy what we were doing, and to PERMISSION to do things incorrectly.

For the last few weeks we’ve been pounding through the Frankie Do, really teaching-via-drilling, standing at the front of the room and just pounding information into the students’ brains. They’ve worked very hard, we’ve worked very hard, we’ve all learnt a difficult routine. But I haven’t found it particularly satisfying teaching. And while I’m seeing lots of good quality dancing (people are getting fitter and learning lots of good steps), I’ve not had those moments of inspiration that I teach for.

I want to repeat, though: I’m seeing really good, hard work and great dancing from the students. And I think my teaching partner is both inspiring and challenging as a teacher and dancer – the best combination of motivation, encouragement and role model. But I do feel as though we’ve drawn a route across this territory, and then stuck to it, regardless of landscape.

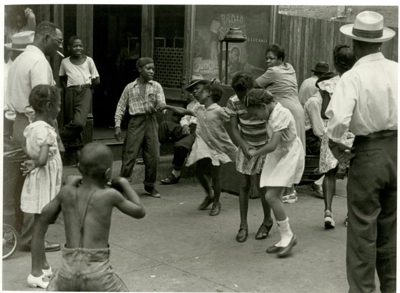

This worries me, as a teacher and dancer. Yes, we do have a duty (I think) as teachers, preservers and revivalists of historic dance to try to pass on a particular vocabulary of dance. We don’t want to lose those historic steps. But I think we miss the point when we insist on word-perfect recreations and performances which demonstrate perfect recall. Vernacular jazz dance is not about uniformity and repeatability. It is about improvisation, innovation and utility.

Simply put, if it doesn’t have a social or cultural or creative function, a step is reworked, or abandoned. If it’s not doing something new (to impress a lover, to win a dance competition, to make a friend laugh), then it’s not useful. And if it’s not reflecting who we are, responding to and articulating how we feel at any one moment through musical play, then it’s not jazz dance. More than syncopation or polyrythms or a swung timing, real vernacular jazz dance has to be alive and socially relevant to who dancers are in that moment.

And when I see our students reproducing that routine, pitch-perfect, with beautifully extended lines, synchronised timing and not a single step mistook or forgotten, something in me gets a bit worried. I’m not sure this is what Frankie would have liked. I’m not sure he would have been happy to see the Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers in that Keep Punchin’ video so perfectly alike. I know Dawn Hampton would SHOUT at us.

But this is the challenge. Students – and teachers – like goals. We like clear measuring sticks. It’s good business sense (it’s easier to sell a block of progressive classes with clear, achievable goals). It’s actually good for the physical standard of dance in a community (dancers who drill get fitter and stronger and have better memories). And it gives everyone involved a sense of satisfaction and pride. As a team, we’ve conquered this routine. We’ve committed it to memory. We’ve ticked that box.

However, classes with clear lists of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’, and this emphasis on perfect memorising and reproduction as ‘right’ and anything else as ‘wrong’ aren’t terribly good for the self esteem. They create not only an emphasis on correctness, but also an air of anxiety or pressure to get it right. Which doesn’t make for a fun learning environment. The idea of ‘making perfect mistakes’ or ‘being enthusiastically, wonderfully incorrect’ is much more liberating, much more exciting. We don’t want to ‘get it right’ in jazz dance, we want to enjoy ourselves. The hard work can be a by-product of this.

And then I think about that little spark of humour in the way that student used to drop their shoulders and tilt their head. Sure, it wasn’t the best posture, and it did impede their range of movement. But it was utterly unique. Instead of having that student explore just what might happen if that shoulder drop was exaggerated to the point of immobility, we straightened them up. Instead of encouraging them to find a way to get the same look, but with extended arms or a lifted chin, we ‘tidied them up’. In itself, this tidying isn’t a bad thing. It’s important for dancers – for moving humans – to learn to use their muscles and bodies efficiently and safely. And good quality muscle use does lend a sameness to dancers’ movements. But we deliberately – or unconsciously – sought out a sameness and uniformity.

That’s all very well for me to say here. How else were we to teach a routine?

Firstly, I think we could have taken time for each person in the room to explore many different ways of performing a particular move. A shorty george and a boogie forward and a broken leg and a fall off the log are all just different ways of walking. They’re all just individual variations on a walk. And how did we develop all these different ways of walking if we didn’t experiment with walking in the first place, until we’d pushed it so far out of shape that it’d become a strange, knock-kneed hip-hitching stagger? A super-cool, finger-tip swinging swagger? A clunking, drop-to-the-ground parody?

It takes much longer to learn a routine if you take all this time to experiment, but then, we often don’t retain a routine anyway if we don’t constantly practice. So why not focus on learning to move, rather than learning to move ‘correctly’ in the class?

I think that good teaching should be about good learning. And good learning is really best achieved through play. And nothing is better for play than dance. Vernacular jazz dance is extra perfect because it embodies delight, joy, laughter and satire, derision and parody. It’s about competition and one-up-manship and pushing yourself just a little bit further, til you’re really just a bit uncomfortable. And it’s also about laughing and laughing and laughing.

One of the most useful things I’ve learnt about teaching is that reminding students that ‘perfect mistakes’ are an essential part of learning to learn. If you don’t take risks, and don’t commit your weight properly to a step, you don’t realise that uh-oh, you can’t do that kick with that foot because you’re standing on it. You end up hovering in place, failing to commit to anything, not making any mistakes, and not really learning anything either.

So I tell the students “Make the best mistakes you can. Be confident in them”. We haven’t said that to our students in a while.

Working with routines has also meant that the students spend all their time watching us at the front. There’s an anxiety in the room, an anxiety about making a mistake or forgetting a move. Students won’t look away, just in case they get it wrong. They get really worried if we stop demonstrating and they have to do it on their own. As soon as I saw that, I thought ‘we are doing something very wrong here’. After all, what’s social dancing, if not creative play, where the goal is to metaphorically take your eyes off the teacher and explore the limits of your own awesomeness?

Somehow we’ve shifted from our earlier ethos of ‘just do your mistakes with confidence and people will assume you’re doing a variation’ to ‘get it right.’ This doesn’t make for particularly happy classes. And I’ve started to feel less happy in my own dancing as well, as I inhale this unspoken emphasis on ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. I can’t remember the last time I spent time working on just one step in front of a mirror, trying to find the strangest, most unusual way of moving. Now I spend a lot of time worrying that I’m not ‘doing it right’ and that somehow my not-right-ness will ruin the student’s learning.

When what I should be doing is reminding myself that teachers don’t just pour the knowledge into students like tea into a cup. They’re guides to learning, where the students – not the teachers – are the most important people in the room. At the end of the day, the teacher doesn’t even need to be a better dancer than the student. They need to be good facilitators and class planners, and they need to be observant and helpful, encouraging students to figure out how best to move their own bodies. It helps if the teacher has a lot of experience, and is continually expanding their own learning and experimentation with ideas, but we should expect – hope! – that the student will surpass the teacher! Or if not surpass, then take a completely different and unique path to happiness on the dance floor.

I think, though, it’s a difficult balance to negotiate. If you do want to become a ‘good’ dancer, a certain amount of drilling and repetition and precision is necessary. You really do have to learn those historic routines. But I think that if this is all there is in a class or personal practice regime, this is all there will be in your dancing: repetition. Yes, we will be perfect, but we will be perfectly dull.

So how _do_ you teach in a way that at once involves this sort of strength and fitness training through repetition and innovation and inspiration and individuality?

Firstly, I like to think about learning-through-experimentation. What does happen if I lift my arm from the hand? What if I lift the arm from the elbow? The shoulder? How do these differences change the look, the feel of the movement? What happens to the angle of my leg if I rotate from the hip rather than the knee? What happens if I perform the move once with the rotation from the hip, and the next time from the foot?

I think it’s important to learn certain fundamentals of biomechanics and efficient movement, but it’s just as important to experiment with the range of movement and strength we have available to us at any one time.

Secondly, I think we need to periodically return to the ‘fundamentals’ of dance – the triple step, the rock step, the knee bend – in a mindful way, to see if what we’re doing habitually is actually productive or innovative or useful.

Teaching by rote or drilling discourages mindfulness and self-awareness. Progressive learning discourages returning to fundamentals because there’s a sense that the ‘beginner parts’ are ‘for beginners’ and to be ticked off and then moved on from, to other, more important/challenging/interesting things.

Thirdly, I think we have to be continually reminding ourselves that dance should be about joy and creativity. We should enjoy what we are doing. If it doesn’t interest us, or if it causes us anxiety or unhappiness, then we should move on. Frustration can be useful, but unrelenting obstruction can be disheartening and ultimately discourage.

Yes yes, this is all very well. But how do you fit this into a one hour class each and every week? It’s much harder to accommodate diversity in learning styles, and it’s really, really hard to encourage diversity in practice.

Some things I might I will do in class to achieve these sorts of learning and teaching goals:

- Move away from just teaching routines (even historic ones) and teach ‘fundamental jazz repertoire’ classes. Instead of teaching one correct way of doing each move, though, I’ll coordinate a class where students explore the movement, to its and their limitations. We don’t have mirrors, so we’ll have to use the next best thing – our peers. Some group work where students watch and observe each other, and then demonstrate in turn (or seek to reproduce what they see) and teach each other will be helpful.

- Reinterpreting iconic routines. We tend to think of iconic choreography as dinosaur blood in amber, to be preserved and then reproduced perfectly and minutely, without variation. But even in the ‘olden days’, the ‘key choreographies’ were interpreted and revised on the social, competition and performance dance floors. That’s why we have so many versions of the shim sham, the tranky do and the big apple. While I’d like to encourage the idea that each interpretation is equally important, the olden days dancers would have been fiercely competitive. The status of being ‘best’ motivated innovation as much as – if not more than – anything else.

In practice, we’d begin with an iconic routine (the shim sham is always nice), and then we’d work on our individual interpretations. The challenge, though, would be on producing interpretations that were actually good, solid dancing, and not just a series of excuses for not learning the steps. It would have to be mindful interpretation, where the students push the limits of a shape or rhythm and take it to new places deliberately.

- Spend more time looking at how to develop an ’emotion’ or ‘vibe’ or ‘style’ for a routine. I’ve joked about the fact that most solo charleston competitions we see have the same emotional ‘feel’ – kind of manic cheerfulness. We don’t see ‘angry charleston’ or ‘vain charleston’ or ‘indolent buffoonery’ charleston. But how do we create these personas or performances in a set choreography? How do we actually use our bodies to communicate these things? A slumped shoulder can mean dejection. But the contrast between lifted shoulders and a suddenly dropped gaze, shoulders and head can really communicate dejection. And how do we communicate the difference between parody and sincerity?

Again, all this takes experimentation, mirrors and team work.

- Changing the layout of the room, and the use of space in class. Rows is an effective way of drilling, but it’s terrible for team work and non-teacher-centred camaraderie and learning in class.

I think, most importantly, I have to remind myself that dancing is fun. It’s wonderful, clever and challenging stuff, but it has to be fun. Or what’s the point?