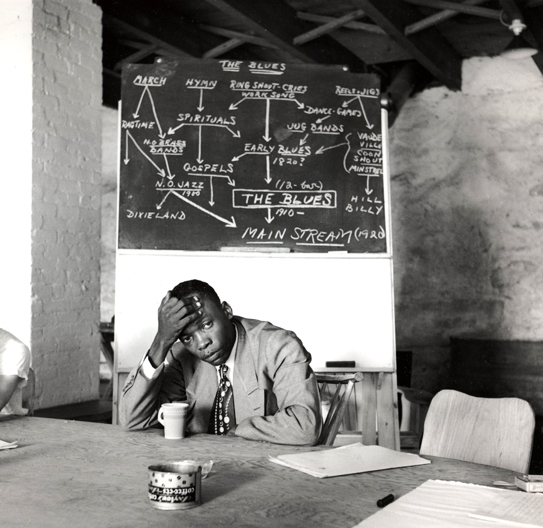

I’m very interested in discussions about history and historical research. I’ve written about a million billion times before (this post ‘Try To Write About Jazz’ sums up some of my thinking). One of the things I’m most interested in is the way dancers use history. We do a lot of things with historical narrative and historical texts. People use it to justify sexist behaviour (a friend of mine uses the excellent term ‘retrosexists’), they use it to present their dancing as more important (because it is more historically accurate), they use it as content for dance classes (eg we teach particular historical routines), they use historical photos and art work in their own PR activities, they use old magazines as guides to historically ‘accurate’ fashion…. The idea of ‘history’ as a resource is a very powerful one in the modern swing dancing world.

Before the internet (when? yes, in the olden days), a lot of this historical knowledge was shared face to face, by phone, on video and film and in letters and books. I’ve talked about this in terms of ‘cultural transmission‘ – the movement of ideas and practices between cultures (and generations and communities and….). Then the internet happened, and then youtube happened. I wrote about this in a journal article a few years ago, and my favourite part was the concept of ‘stealing’ in jazz dance.

Which is why I tend to take the position that if you want to be awesome, you’ve got to keep ahead of the curve. You have to be the person who’s getting stuff stolen from. You have to be the DJ who presents that new song, which every other DJ then plays – so you gotta keep looking for new music, and improving your skills so you know when to pay that new great song. You have to be the dancer who first does that step in a comp, which every other dancer then uses in comps and teaches in classes. This sort of competitive copying pushes us further, and makes us more creative.

But to be really creative, when you’re stealing that step/song/idea, you’ve got to present it back to the community in a new and improved form: you gotta make it better when you do it your way. Or else that crowd of fierce hoofers in the balcony seats are gonna drown you out with enraged tappeta tappetas.

I’m absolutely enamoured with the idea that we can steal a dance step. I’m fascinated by the way power (cultural, class, social, economic, etc) informs how and when and if we steal ideas and dance steps. In that article I argued that African American dance, in the early days (ie the slave days) was about subversive, underground power. I talked about the idea of appropriating dance steps as resistance, and I’ve used the cake walk as an example.

I’m not hugely interested in whether or not something is ‘historical accurate.’ But I am interested in how people use the idea of ‘historical accuracy’ to justify their dancing or thinking: “You must wear garters, because women did in the 1930s” or “You must play 1930s big band swing because that’s what dancers heard in the Savoy ballroom” or “You must learn to dance on the social dance floor only, because that’s how people learnt in the 1920s.” I am certain that in reading those statements you immediately thought of a dozen counter arguments: “Not every woman wore garters in the ’30s” or “I’m not living in the 1930s, so why should I wear garters?”, “People listened and danced to small bands at house parties in the 1930s, so why can’t I listen and dance to small band recordings?”, “Dance classes were a huge industry in the 1920s!”

I don’t really think it’s worth pursuing these sorts of arguments. But I do think it’s absolutely fascinating to look at the way uses of history (and historical ‘evidence’) can help us map patterns of power and influence. But then, I’m not a historian, nor have I ever claimed to be. If I had to mark my place in a discipline, it’d be feminist media studies, or feminist cultural studies. And we lack data, donchaknow. But then, that sort of demarkation of discipline (and defensiveness) really only makes sense in a university context. And I am not writing or working in a university.

I’ve just read this post, Google-historians, as linked up by Follower Variations. That’s the blog where I find most of the interesting bits and pieces about dance in the wider online swing discourse. I rely on blogs like this for linkies because I’m generally not all that interested in reading a lot of blogs about dance. Most of my online reading is in more hardcore feminist and lefty territory.

But my interest was caught by Harri’s post about ‘Google-historians’. It has a decidedly combative tone, which of course provides the reader with a ‘hook’ – a way into the text. Which is why I think people luuurve to get all up in my blog posts that use all caps, rather than my (much more interesting) posts about jazz discographies or vegetarian cooking. I can’t imagine why people don’t want to read all about which musicians played in which sessions of which bands on a particular date. People love history, right? Right?!

I’m not entirely sure what overall point this ‘Google historians’ post is trying to make: is it ‘stop using google!’, or ‘go to dance classes!’ or ‘cite your sources!’ or ‘don’t simplify history!’ ? I started writing a comment asking the author which of these it was. And then I realised that perhaps all of these are the point. Below is a comment I wrote there. I shouldn’t have written such a long comment on someone’s blog post, but, well, fuck. I write a lot when I’m interested. If I’m not interested, I’ve got nothing to say. But I figured I’d reproduce the comment here, in the spirit of not-thread-hogging.

—————————————————————-

I think I need some clarification of your thinking, Harri.

Are you arguing that any researcher who uses just digital sources is going to be full of rubbish?

I can’t agree with that. There’s lots of important stuff to be gained from a little super-powered googling. I’d argue that the important part is not the tools you use, but the way you read the material you find. It’s important to be critical (in the sense of critical thinking, where you ask questions about veracity, accuracy, ideology, context and so on), to be self-reflexive (how is who I am and my ideas about the world affecting the way I read this text?), and to seek out substantiating and corroborating sources.

I’d argue that any historian worth their salt should use a range of sources (primary, secondary, tertiary, etc -> speaking to people who were there; reading newspaper and first person accounts of people who were there; reading informed accounts of events by insightful observers). There are a whole host of digital sources (which you can search using google, which is after all just a powerful search engine – just a particularly clever index), and they can be very useful.

For example, if I wanted to find out about Australian/British responses to a certain dance hall, I might find this Trove search quite helpful. Trove is a very reliable tool, aggregating metadata from a host of reputable Australian digital collections. The most exciting of these (I’ve found) is the series of digitised Australian newspaper and magazine articles.

If I wanted to know what sort of film footage was available, so I could see what those newspaper stories were all about, I might search the catalogue of the National Film and Sound archive, the most reputable source of audio-visual material in the country.

I could use Pandora (a website archiving service run by the National Library) to access a history of the Trocadero in Sydney which includes first person accounts from people who were there.

I could use Youtube to search for some footage from the events described in those pieces, and then I could use google to find a ‘legit’ source for this film (in this case the NFSA).*

But as we all know, this isn’t going to be enough for a really comprehensive historical survey. We’d need some first-person interviews. But all these digital sources are useful for finding out who we should be talking to. Who are the dancers mentioned in the newspaper reports? What do the dancers in the films look like? And so on and so on… Even if we do find a real person to talk to, there are going to be challenges. I remember Peter had written a really good how-to for interviewing older people about dancing on DanceHistory.org, touching on things like not rushing, being polite, being careful with emotive topics, etc etc.

Secondly, though, I think it’s impossible to get an ‘objective’ or final, authoritative history of a topic. So, for example, there’re a number of competing and equally authoritative stories about things like what it was actually like in the Savoy ballroom. Some of these stories are just completely made up (and I do like the idea that Al and Leon might have told Marshall Stearns a heap of lies – lol!), some are inaccurate because the person telling the story was mistaken, and some conflict simply because the story tellers had different experiences in the Savoy (eg a young white woman might have a different experience than an older black man). So if I do manage to chase down dancers from the Trocadero, using all those digital sources, there’s no guarantee that any single story will be enough to gain a bigger idea of what it was like.

I’m guessing this is your point? That we need to treat history as a complex, changing, moving story, rather than a simple one-off meta-narrative?

The next challenge, though, is how you actually go about stuffing history into your dance classes. When I teach, I like to reference the people who told me the story (eg “Norma tells a story in a clip filmed at Herrang in year X where she said…” or “Lennart pointed out that such-and-such was very young when they heard this story”). That seems important, and I think it encourages students to learn from a whole range of teachers (Norma and Lennart and…), which is a good thing for me to do, as a person who invites those teachers out to teach workshops and then needs to promote them** :D I think a lot of dance teachers are reluctant to encourage their students to do their own research and thinking, or to learn from other people. For the usual reasons.

But if you’re telling these historical stories in class, you have to keep them really short – the less talking, the more dancing in a dance class, the better (ie the more viable) they’ll be. You can’t just list a whole heap of facts and hope they’ll stick. You have to use story-telling carefully, integrating it with the physical movements and pacing of the class. This takes preparation, skill and experience. There was an interesting discussion on Jive Junction, years ago, where someone pointed out how Frankie’s story-telling skills improved over the years. He became a better story teller. And not every dance teacher is that good at telling a story.

I guess, what I’m trying to say, is that using history in dance culture is hard. You’ve got to have good research skills, you’ve got to have good story telling skills, and you’ve got to have the time to do all this. Here in Australia, we rarely see old time dancers – maybe one a year, if we’re lucky. And bad luck if you can’t make it to that event. So we’re necessarily restricted to using secondary and tertiary sources. And the internet.

Most dance classes are a labour of love, with very little financial return, and a whole heap of political complexity. We shouldn’t be surprised that some people are just crap at it. They might instead be very good at teaching people how to use their bodies. I think we should be kinder to dancers who’re actually talking about history (many don’t!), cut them some slack. And possibly point them in the direction of some useful research.

*NB I used lindy penguin‘s blog post for these search results.

**In fact, I have a ‘how to include history in your classes’ class planned for the next Little Big Weekend teacher-development session (11-12 May 2013, with Lennart and Georgia, yo. SYDNEY). HOW EVEN DOES IT WORK?

NB Laura gives an example of how people tend to do research in the dance world in her post Pitch a Boogie Woogie and Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers: it’s a combination of archival work and making contact with other historians who have access to other sources. As with any interesting work in the modern lindy hop world, the best projects are collaborative, and rely on personal contacts, networks of peers, and the generosity of dance scholars (in the dance scene).

I’ve recently discovered the 1951/52 stuff by the Johnny Hodges band on this dodgy digital download album

I’ve recently discovered the 1951/52 stuff by the Johnny Hodges band on this dodgy digital download album  The Never No Lament: the Blanton Webster Band 3CD set was one of the first serious Ellington CDs I ever bought (though it was a lot cheaper then than it is now), and I bought it because dancers and DJs I admire recommended it on the

The Never No Lament: the Blanton Webster Band 3CD set was one of the first serious Ellington CDs I ever bought (though it was a lot cheaper then than it is now), and I bought it because dancers and DJs I admire recommended it on the  I used to have a long bus commute to uni which I’d spend reading my way through Gunther Schuller’s book The Swing Era: the Development of Jazz 1930-1945 and listening along with my whole Ellington collection on my ipod. I read music (haltingly), and Schuller spends quite a bit of his time examining scores in detail. I’m not entirely convinced by everything Schuller says, but Schuller’s is an interestingly scholarly approach to a musician who was as comfortable with concert halls as dance floors.

I used to have a long bus commute to uni which I’d spend reading my way through Gunther Schuller’s book The Swing Era: the Development of Jazz 1930-1945 and listening along with my whole Ellington collection on my ipod. I read music (haltingly), and Schuller spends quite a bit of his time examining scores in detail. I’m not entirely convinced by everything Schuller says, but Schuller’s is an interestingly scholarly approach to a musician who was as comfortable with concert halls as dance floors. Most of my love for Ellington is centred on his earlier stuff and on those small group recordings. My interest tends to wane at about 1950, to be honest, but that’s not a strict rule. There’s a song called ‘B Sharp Boston’ which Ellington recorded in 1949 and which used to get around on those dodgy ripped compilation CDs as ‘Sharp B Boston’. I picked up the Chronological Classics Duke Ellington Orchestra 1949-1950 CD in about 2006, and discovered it was actually called ‘B Sharp Boston’, and that there was a bunch of other great stuff on that CD that makes for top DJing (I’ve written about this before in

Most of my love for Ellington is centred on his earlier stuff and on those small group recordings. My interest tends to wane at about 1950, to be honest, but that’s not a strict rule. There’s a song called ‘B Sharp Boston’ which Ellington recorded in 1949 and which used to get around on those dodgy ripped compilation CDs as ‘Sharp B Boston’. I picked up the Chronological Classics Duke Ellington Orchestra 1949-1950 CD in about 2006, and discovered it was actually called ‘B Sharp Boston’, and that there was a bunch of other great stuff on that CD that makes for top DJing (I’ve written about this before in