scary cycling safety posters

musicians’ local

to a top scientist

Radfahrer – Achtung

YAH

that stupid bra colour thing

Ok, so there’s thing on faceplant where you’re (as in you, women) are encouraged to post the colour of your bra in your facebook update, but not to explain what you’re doing. I’d dismissed this as just one of those fb games and not really worth thinking about. As it’s progressed, colours began popping up in people’s fb updates, and men began asking about it. As this snowballed, I started hearing a mild alarm bell tinkle.

I’m not sure I’m ok with public games that ask women (only women, mind you) to discuss their underwear in a privately owned public forum. I’ve also been feeling a bit strange about the edge of titillation here. As you might expect, the more purile male faceplanters immediately sexualised the game. The ‘keep it secret’ element seemed to fuel the sexy element. This really emphasised the fact that women’s underwear – bras, specifically – are sexualised objects.

I know this kind of sounds a bit durh to type out loud, but sudden association of this fairly silly but minor bit of fluff with breast cancer really made me stop and think.

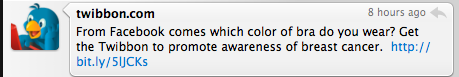

The tweet that caught my eye:

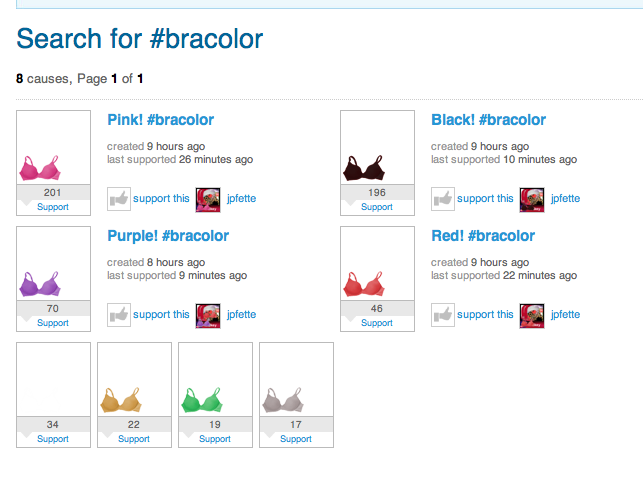

The page at the end of the tweeted link:

Lauredhel’s Hoyden discussion of similar issues is probably a lot better researched and thought out than my little post.

When a friend essentially called the faceplant bluff, revealing her bra strap in a photo accompanied by characteristically dry commentary, the sexualisation was undone…. to a certain extent. I think that the important elements in this entire non-event are/were the idea that: a) women’s bras are inherently sexy; b) bras are sexy because they are/should be hidden; c) women’s bras are sexy because they have something to do with breasts; d) women’s breasts (and women) are _always_ objects for male sexual desire. My unease lies with the effects of this association on/in breast cancer awareness campaigns and on public perceptions of breast feeding.

To return to faceplant, though… The most concerning The fucking irritating part of this is the gradual seeping-in of comments from men on women’s updates on faceplant which read as sexual harassment. The majority of these have been from your standardly socially inept swing dancers, but I think an attendant unwillingness to call men on this type of commentary indicates the pervasive tolerance of chauvinism in swing dance culture. The online world simply allows us to point to specific, recorded examples of this behaviour.

More interestingly, it’s worth thinking about the consequences of sexual harassment in this context. In basic terms, sexual harassment works to keep women feeling unsure of themselves, powerless to control the terms upon which they – and their bodies – are considered in public dance/online discourse. This is significant with dance, as women’s bodies are necessarily open to the public gaze, and there is a continuing negotiation of the sexuality/isation of women’s bodies on the dance floor. Don’t get me started about fucking high fucking heel fucking shoes!

Let’s talk context. There are usually more women social dancing than men, hence the term ‘follow heavy’ and the explicit suggestion that too many women is a bad thing. For other women. Having uneven numbers of follows and leads at a dance (where following and leading is clearly gendered) results in one group (almost always the follows, almost always women) competing – either explicitly or implicitly – for the attention of men, in order to secure a dance.

This results in tensions and competitiveness between women in swing dance culture, and, rather than working together to achieve positive outcomes, women tend to work to secure their _own_ dances/happiness, etc. This situation is exascerbated by the large number of younger women (the teens to twenties) and the emphasis on physical appearance (both in terms of conventional beauty but also performances of physical dancing ability) in social swing dance. It also serves to secure the confidence of male dancers. Simply put, it feels good to be competed for. It also improves your dancing to be on the floor, dancing all the time. And when you’re on the floor all the time, dancing and feeling and looking confident, your status rises and, well, you get a feedback loop which recreate the same old boring gender dynamics.

Booooring.

As you can imagine, this shits me TO TEARS. Tears of rage and FURY.

But rather than sit about being angry and resentful and generally furious, I’d rather get proactive. After all, one of the side effects of this bullshit – patriarchy – is to reduce women in confidence, to keep us sitting idly, frustratedly, powerlessly by. These are things that I do to get around this bullshit:

- I lead

- I dance alone

Simple, and effective. In both scenarios I dance with women and I side step the broader challenges of men-leading-women on the social dance floor. It makes me feel good to develop new skills, and it makes me feel good to simply step out of that unhealthy cycle of self-blame (aren’t I a good enough dancer/pretty enough/young enough/cool enough) and rage (wtf is wrong with you?!). I’ve also found that setting an example to other women is important. Because I’m not the only one standing there, bored, I find that other women are just as keen to get dancing – with me, alone, with each other. And I’m also very willing and keen to follow the example of other women leading or dancing alone.

One of the most important parts of this process is stepping out of the silent to-ing and fro-ing of unspoken competition between women. I think the unspokenness is significant, just as with the bra colour thing. As soon as you simply stop participating in a silent cycle that disadvantages women, you break it.

a new 8track: 9 songs I might play for flappers tonight

I’m putting together some music for tonight’s set at Swingpit in Newtown. A discussion about ‘fast’ music on twitter + some low-level interest in 20s charleston and solo jazz encouraged me to revisit some appropriate music in my collection.

I put together an 8track of things I’m thinking about.

(clicky).

There isn’t as much solo charleston in Sydney as there was in Melbourne when I left, though there is a bit of solo dancing generally. Very little hot 20s or 20s-style music is played here at social events. I think we might need a rash of workshops on 20s dances generally to stimulate interest and skills… actually, there’s definitely interest, it just feels as though people don’t really feel confident or know what to do out there to this stuff.

Personally, I’d really like to learn some eccentric 20s partner dances.

At any rate, this 8track is a list of songs that I am considering playing tonight. The sound set up at this venue is very shit, so I’m avoiding the lofi action. Which is a crying shame. But there you go. I had to add the Armstrong version of Oriental Strut, though, as I LOVE it. It also makes me think about Woody Allen films as he plays it quite often in his films (especially Bullets Over Broadway) and I’m trying to get a copy of Sweet and Lowdown.

I’m also a bit hot for Jabbo Smith atm, so I had to add Jazz Battle as well. Same with Johnny Dodds.

I stole the image for the 8track from here.

Track details:

Rhythm Spasm Rhythm Rascals Washboard Band 315 1995 Futuristic Jungleism 2:33

San Les Red Hot Reedwarmers 285 2007 Apex Blues 4:45

Jubilee Stomp David Ostwald’s Gully Low Jazz Band (Howard Alden, Mark Shane, Herlin Riley, David Ostwald, Ken Peplowski, Randy Sandke, Wycliffe Gordon) 278 2006 Blues In Our Heart 3:22

Stampede Randy Sandke and The New York Allstars 260 2000 The Rediscovered Louis And Bix 2:47

Jazz Battle Jabbo Smith’s Rhythm Aces (Omer Simeon, Cassino Simpson, Ikey Robinson) 259 1929 All Star Jazz Quartets (disc 1) 2:41

Hop Head Charlestown Chasers 250 1995 Pleasure Mad 2:57

New Orleans Stomp Johnny Dodds’ Black Bottom Stompers 244 1927 Golden Greats: Greatest Dixieland Jazz Disc 2 2:47

Oriental Strut Firecracker Jazz Band 228 2005 The Firecracker Jazz Band 2:36

Oriental Strut Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five (Kid Ory, Johnny Dodds, Lil Armstrong, Johnny St Cyr) 191 1926 Hot Fives and Sevens – Volume 1 3:03

vegie lasagne

layers:

– paneer (yes, again)

– baby spinach

– red slop: canned brown lentils, canned tomato, onions, garlic, fresh basil, olive oil. Would usually include mushrooms, but they were skanky

– very think slices of butternut pumpkin

– top layer of sliced basic and tomatoes.

It was finally topped with a layer of ordinary yellow cheese (some sort of cheddar situation).

horror trifle

Looking over the CSIRO trifle recipe, I’m grossed out. What a pale, stupid arse version of a very nice dish. Berries are in SEASON in a southern hemisphere christmas! What about those lovely stone fruit?! Jelly is WRONG in a trifle!

The ONLY trifle to have is pavlov’s cat trifle!

ya supernatural romance

Remind me to write about Lili St Crow‘s Strange Angels series.