In this post I’m going to talk about how I organise my collection for DJing, as the topic came up in the DJ session at Herräng. I’m also going to talk about how I use this organisation and search tools to actually DJ ‘on the fly’, choosing and combining songs for particular effects. In that Herräng session some DJs said they don’t organise their collections at all, some micro-manage their collection, and some are in between. From what I’ve seen, how and whether you organise your collection really depends on your personality, how you think about music and approach DJing, how good your memory is, and how large your collection is.

I use a system that works for me, because I have a really, really bad memory (I need to preview), and because my collection is getting quite big these days. I don’t listen to music during the day when I’m working, so I’m not on top of my music the way someone like Peter Loggins is. He has a phenomenal memory of his music, with a good ear for style and artist, as well as speed and energy. I’m the opposite, so I need a system. But I’m not a crazy micro-manager, because I like to leave something to chance and creative accident.

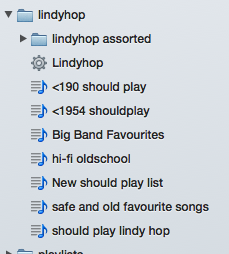

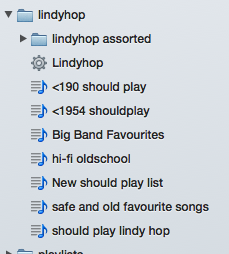

I have a list of songs in my collection that I’ve actually titled ‘safe and old favourite songs’, and this is in my ‘lindy hop’ folder (I also have a ‘blues’ folder’ and an ‘assorted folder’ – for when I DJ blues and random soul gigs, respectively).

This ‘lindyhop’ folder also includes a smart playlist called ‘lindyhop’, which selects songs by rating, genre, and a couple of other things. This helps me weed out my Fleetwood Mac when I’m DJing. :D

But I often consult my whole collection when I’m DJing, as it gives me access to all my songs when I’m trying to find a particular artist or song I can’t quite remember.

The ‘lindyhop’ folder also includes some hand-picked playlists of songs called ‘<190 should play', '<1954 should play', 'Big Band Favourites', 'hi-fi oldschool', 'new should play list', 'safe and old favourite songs', and 'should play lindy hop'. Two of these are lists of songs that I think I 'should play'. These are songs that have caught my eye recently, and which I'd like to put into a set. They're essentially short lists of my current favourites or things I'm digging. '<190 should play' is a list of my songs under 190bpm, which I don't actually use that often when I'm DJing. '<1954 should play' is a playlist I use a lot in preparing for DJing, and in DJing in the moment - it's a list of my 'old testament' music, which is what I really think most of my lindy hop DJing draws on.

The other important list is the 'hi -fi oldschool' list, which includes all the recordings by modern bands who do recreationist stuff that I own. I'm beginning to think I need a third key list, called something like 'new testament swing' for 1950s big and small bands. But that'd be pretty much just the same as my 'kansas small/big' list :D

At a lower level, I divide my music into a few key groups which use a controlled vocabulary (a term I used in my info management course - I use only a few select terms to identify song/band types). These groups include:

2000s hi-fi small female vocal

2000s hi-fi small female male vocal

2000s hi-fi new orleans small male vocal live

2000s hi-fi new orleans small male vocal

2000s hi-fi new orleans small female vocal

1990s hi-fi small female vocal live

1990s hi-fi small female vocal

1990s hi-fi big female male vocal

...and then similar variations with the decades. The key terms are vocal, small or big, instrumental and hi-fi in these groupings. The years are less important than the hi-fi term - because the modern stuff is almost always hi-fi. You can see how I have some redundancies happening here. But redoing my whole collection's groups would kill me.

Things get more specific when I get to the 1960s.

1960s hi-fi kansas small male shouter vocal

1960s hi-fi kansas big instrumental

1960s hi-fi kansas big instrumental live

1960s hi-fi kansas big female vocal live

And there's a lot of this stuff for the 1950s stuff. This stuff is pretty much my new testament Basie collection, and my Witherspoon/Big Joe Turner stuff. Band size is also important: small, large. And instrumental, vocal, male, female are also important.

You can see that city is important. I use these city terms more when I get into the 40s, 30s and 10s: kansas, new orleans, chicago, new york. I also use the term 'new orleans revival' when I'm talking about people like Bechet in the 30s and 40s, though that's a bit of a redundancy too. These city terms are more about musical style than city of origin - so you get some Louis Armstrong with the new york term attached, even though the man was 100% NOLA.

1940s small western swing male vocal (Bob Wills, anyone?)

1940s small western swing instrumental

1940s small male vocal jump blues (Louis Jordan?)

1940s small male vocal group (that's Cats and the Fiddle Right there)

1940s small male vocal

'1940s small male vocal' is a small group with a male vocalist, recording in the 1940s. It can include Slim and Slam, Milt Hinton, Skeets Tolbert, etc - a very varied group). The '1930s small male vocal' is very similar.

I'm using these terms to aid my searching when I'm DJing, not to help me catalogue my music. So short, simple, useful search terms are important. I'm also pre-selecting for rating (eg that lindy hop folder has only songs I've rated 3 stars or higher - excluding stuff where the quality is shithouse, or songs I haven't sorted through yet, etc etc) and tempo.

It's also very important to know something about the history of jazz - I know that 'kansas male shouter' will give me Jimmy Witherspoon, Big Joe Turner, etc, because I know those blokes were singers from Kansas who sang in that 'shouter' style. I also know the difference between 'chicago' and 'new orleans' is to do with decade as well as style - NOLA musicians who moved to Chicago in the late 20s/early 30s have a particular style. And this is related to musicians like the Chicago high school blokes. I know that if I'm searching for 'instrumental' and 'big', it will mean something different in the 1940s and 1920s - 'big' bands were really big in the later decades (a dozen or more musicians), and not so big earlier on (you'd be looking at around 8-11 musicians rather than 15). The extra terms help me deal with the exceptions to these rules.

I don't think I need to list any more of my groupings - you get the idea. This grouping field in itunes is autocomplete, which makes this work much easier. It also makes it important to use a fixed term order, and a fixed vocabulary.

Beyond this, I also organise my collection by bpm, year, rating (using stars - DJable lindy hop needs 3 stars to get into the list, all the safety songs have 5 stars), using the itunes fields. You can see, here, how I'm painting myself into a corner by using itunes. It means that all this data isn't necessarily stored in the song file in a useable way - I'm quite dependent on itunes to help me manage my collection. And as every librarian knows, it's a bad idea to keep your metadata in just one form, dependent on software that has a limited lifespan. ARGH!

I often use the 'date added' field to help me keep track of my newer music. If I've just bought a bunch of new CDs, I want to be able to access them quickly when I'm DJing. I usually search by key word (eg artist or song title), then manage the results by date added. This will help me find that Ellington song I bought last week, when I have >1000 Ellington tracks in m lindy hop folder.

Song title is often the field I search by term, or the way I narrow down my selection when I’m DJing. For example, I’ll be playing song X, checking out the vibe in the room, and think “Hm, I reckon a bit of Basie would go down well now.” Then I search for Basie in my lindy hop. If I’m looking for a particular Basie track – eg 1950s vocal stuff by Big Joe Turner – I’ll narrow the search by adding ‘vocal’. That’ll give me a list of songs that I’ll then look through manually for the right tempo or song title.

You’ll note that I list female before male in the ‘female male vocal’ listings. This is my small attempt to undo the ingrained gender bias in controlled vocabularies. Data ain’t neutral, yo.

All this search term use and collection management is really about my managing my collection before I start DJing, and in my DJing prep before a set. When I’m actually DJing, I tend to go by nose, responding to what I feel in the room. I do find I have particular habits, and tend to overplay some songs. This is when the search terms and tools help me break habits: instead of playing ‘Sent For you Yesterday’ by Basie in the 50s, I might hunt down something with a similarly high energy and rhythm section, but by a different artist.

I find that DJing on shitty sound systems also affects my DJing habits – I lean on more recent recordings these days because the place I DJ at most has the WORST sound system and acoustics ever. A pretty awful result of this is that I neglect my older music, and have, ultimately, lost interest in DJing because that older stuff is what inspires me most.

Once I’ve found a song, I drag it to my previewing app, and listen to it through the headphones. I find it really important to keep one ear ‘in the room’ while I’m previewing – I want to hear how this new song feels and sounds next to the one in the room. I also need to keep my eyes on the dancers while I’m previewing. I watch how they’re dancing and responding emotionally to the current song that’s actually in the room, and I gauge where they’re likely to go, emotionally, in the next song. If they’re kind of tired, physically, I might keep the energy up in the next song, but drop the tempo a bit. If they’re physically fine, but kind of manic and sort of emotionally battered, i might drop the energy but keep the tempo up.

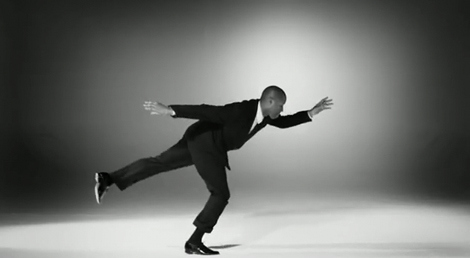

To do this sort of crowd reading, you need to be able to understand what people are feeling by observing their bodies. This is where I think it takes a fair bit of dancing experience. If you have a degree of empathy, you can judge the emotions people are feeling, whether you’re doing it consciously or not. At a simple level, happy people smile. But happy, excited, engaged dancers ‘in the zone’ also turn their muscles on in a different way – the energy reaches their finger tips, they lift their head at a particular angle, they don’t notice anyone around them except their partner, they laugh or show expression unguardedly, and without inhibition. I like DJing for beginners particularly because they are the most free with their emotions in these moments – they don’t have the physical control to be particular graceful or technically precise, but they’re so new to dancing their responses are utterly honest and quite wonderful. And because they don’t have as much stamina, these moments are fleeting.

Ironically, I’ve found that the most creative sets I’ve done recently have been ones where I’ve forgotten my headphones, and haven’t been able to preview – I take more risks, and use my search tools more efficiently. I also use my memory of songs, and how they feel to actually dance to.

I also make selective use of the silence between songs. Sometimes a little bit of extra silence is a good way to give people’s ears and emotions a break. I actually had a moment in Herräng on the last Friday night at the party (where people are peaking, emotionally, and kind of crazy), where the crowd liked the song I’d played so much that they stopped dancing and looked at me and applauded and shouted and stamped so much that I felt I had to acknowledge them in return. That’s never happened to me before, and I felt a bit embarrassed, but I also felt it was only polite to do a sort of smile/wave, and leave a bit of a pause before I played the next song. People needed time to respond to me, and then they needed the usual time to thank their partner and comment on the dance before they left the floor and found someone else, or re-set before the next dance.

There was also a moment in one night (at the previous week’s Friday night party – again the night where people go nuts) where I had to ‘kill’ a jam. There’s an unofficial policy at Herräng where you don’t let a jam go on too long, because it tends to kill the vibe a bit. You end up with song after song of jam, where dancers just keep going into the circle, bringing the shit. That’s totally fine, but you do end up with most of the room standing about watching, and gradually getting physically colder and slipping down the crazy scale til they figure out they’re tired and go get a drink instead of dancing. So the deal is that you let a jam happen for one song, perhaps two at most, and then you kill it.

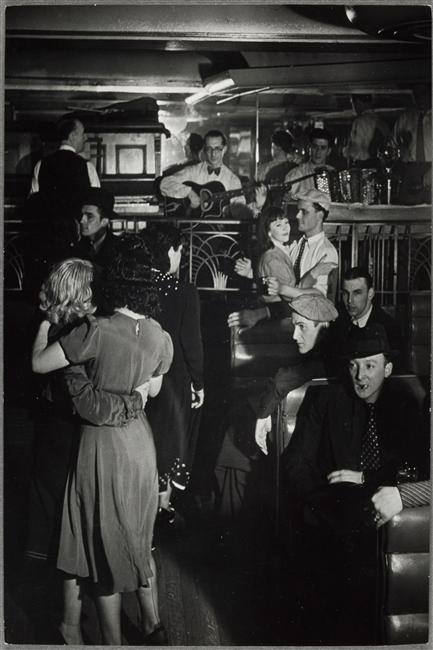

Killing a jam is a challenge in an environment like the Friday party at Herräng. That night I was actually really worried about the dancers. They were absolutely insane. This is what it looked like:

There was a sort of soul circle (a really tiny one – like a jam circle) in one part of the room, a lindy jam circle in another part of the room, and the rest of the room was just packed solid. There’d just been a twist competition, and the room was physically shaking, and I noticed that people in the jam were actually getting physically hurt, throwing themselves about. Usually I work to build the energy in the room, but this time I decided it was time to kill things a bit. I just didn’t really know how to do it. The lindy jam had started at a low tempo, so I couldn’t just drop the tempo. I wasn’t sure what to do. So I decided to just use a longer gap between songs, so people had to physically stop dancing for a moment. But the tricky bit was deciding just how long to let the silence run. I didn’t want them to turn on me. It was just a matter of seconds, but I did manage to kill the jam without killing the vibe. And a fair few people suddenly realised they were bleeding (seriously – bleeding) and crazed, so they left the dance floor and things got a bit more sensible.

It was a hard decision, and this really was an example of micro-managing the dancing through DJing, something the speakers in the DJ session had decided was a bit uncool. But I think it was the right decision. I do consciously manipulate the energy and emotions of the dancers in the room when I’m DJing. I aim to build the energy, to warm the room, and to work people into a frenzy. I want to see the crazy, uninhibited dancing, and I want to see the dancers reach that state of ecstasy that just feels SO good. And because I’m right there with them, I get a contact high too. You can make this work by combining songs in the right way. But it also helps if you’re DJing the right night in the event. Friday night at Herräng is pretty much the right time and place to make people crazy. I also like 2am on Saturday night at weekend exchange. People are relaxed enough to just let go and enjoy themselves, but not so tired that they can’t dance for hours.

There’s also critical mass: a crowd of people is easier to work into a frenzy than a smaller group.

This photo was taken at about 5am, and this group of people had been dancing for hours and hours and hours. They were physically ragged, but quite emotionally happy and relaxed. But there was no way I was going to pull of crazed euphoric mass with these guys. There just wasn’t enough of them. And they weren’t in that place, emotionally:

This approach to DJing lindy hop is what makes me a fairly rubbish blues DJ. I just can’t figure out the right emotional patterns in blues. My instinct to push the energy and excitement up is all wrong. Blues dancers want to push the emotional intensity up, and the tempos down. But I just can’t read the crowd right to pull that off. Mostly because I just don’t blues dance enough to know how to recognise the right feels in the crowd. Same goes with balboa – they don’t aim for crazed, uninhibited flailing about either. They like something a bit more cerebral. But buggered if I can figure out how that works. They just look all uptight and bored to me. Because I just don’t know how to read what I’m seeing, because I don’t dance balboa.

I think I need to end this post here, but I’d like to do so with a note to the effect of longer sets on DJing this way. When you’re DJing for an hour or an hour and a half, you have to come in hard and fast, and hit that peak quite quickly. But when you’re DJing for three hours or more, you have to manage people’s stamina. They just can’t stay that high for three hours – they get exhausted. So you have to work a series of peaks and troughs, over the course of the night. And you have a much greater scope to work with, in terms of emotions.

I think I learnt a lot about working with the other emotions in lindy hop when I DJed at Herräng. Those long sets at later hours (3-6am, for example), are where people are physically exhausted, emotionally open, but also interested in feeling things other than frenzy. You can play the musically complex stuff that stretches their brains and partner connection, but the wall of sound new testament Basie stuff seems a bit blunt and simple for people at this moment. I found that this was where I really needed the original 30s and 40s recordings most – where the musicians were best, the arrangements were inspired, and the performances were nuanced. A greater range of feels for the dancers.

Anyways, this is where I’ll end. Hopefully I’ll get onto another post soonish.