Why do I want to hang onto class when discussing race and ethnicity in dance?

A friend, Superheidi, noted recently that she’s not entirely ok with the way some white dancers use the word ‘race’. She made the point that ‘race’ isn’t accurate; we are not different races because we have different skin colour. We are all one species.

But the social or cultural concept of ‘race’ is still important. I actually use ‘ethnicity’ more than ‘race’. ‘Racism’ is often about skin colour and appearance.

But ethnocentrism is about more than skin colour: it’s about culture and identity.

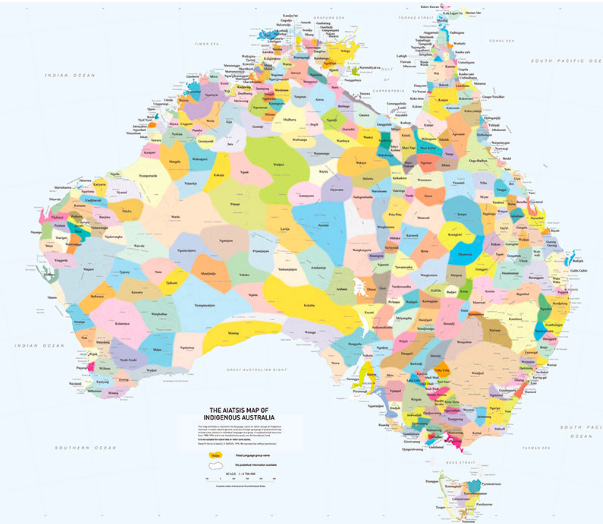

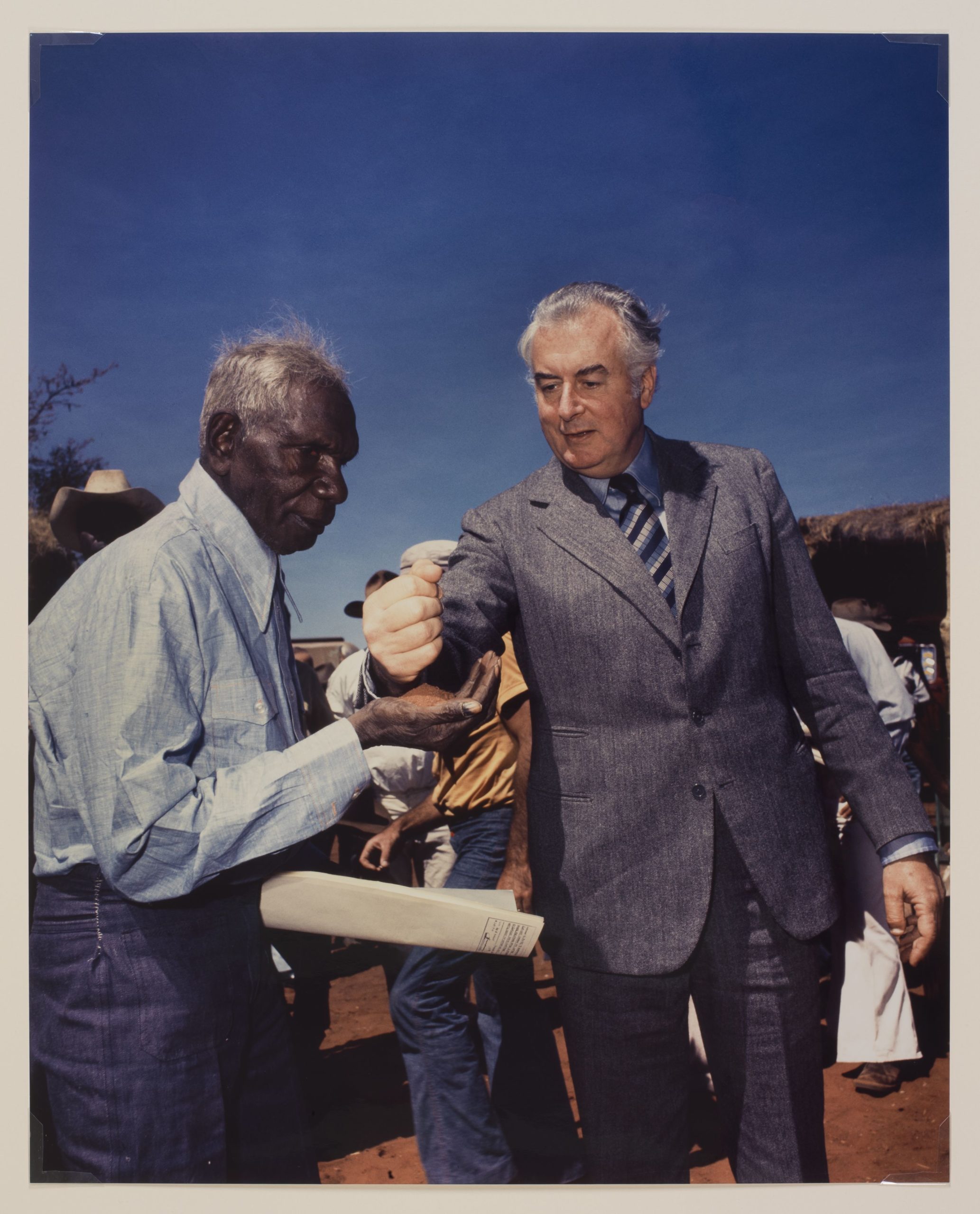

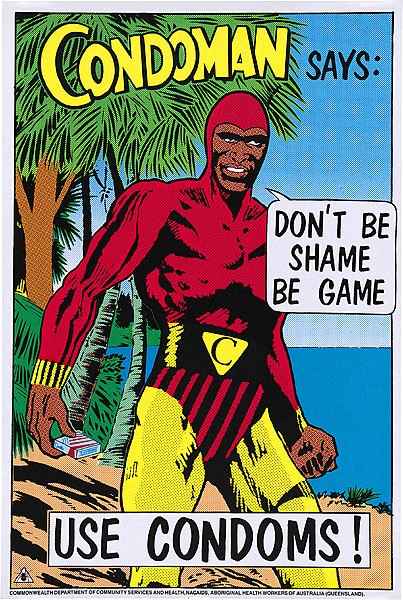

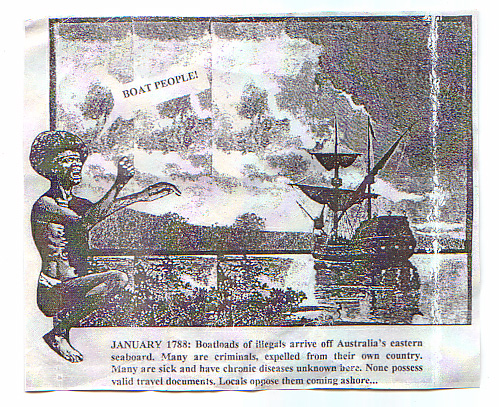

If we talk about ethnicity, we can distinguish between west africans and east africans, african americans and africans. And so on. The important points become cultural and social: who a people are rather than just what they look like. This becomes super important for first nations people who have been displaced from their homelands, especially in Australia after the stolen generation.

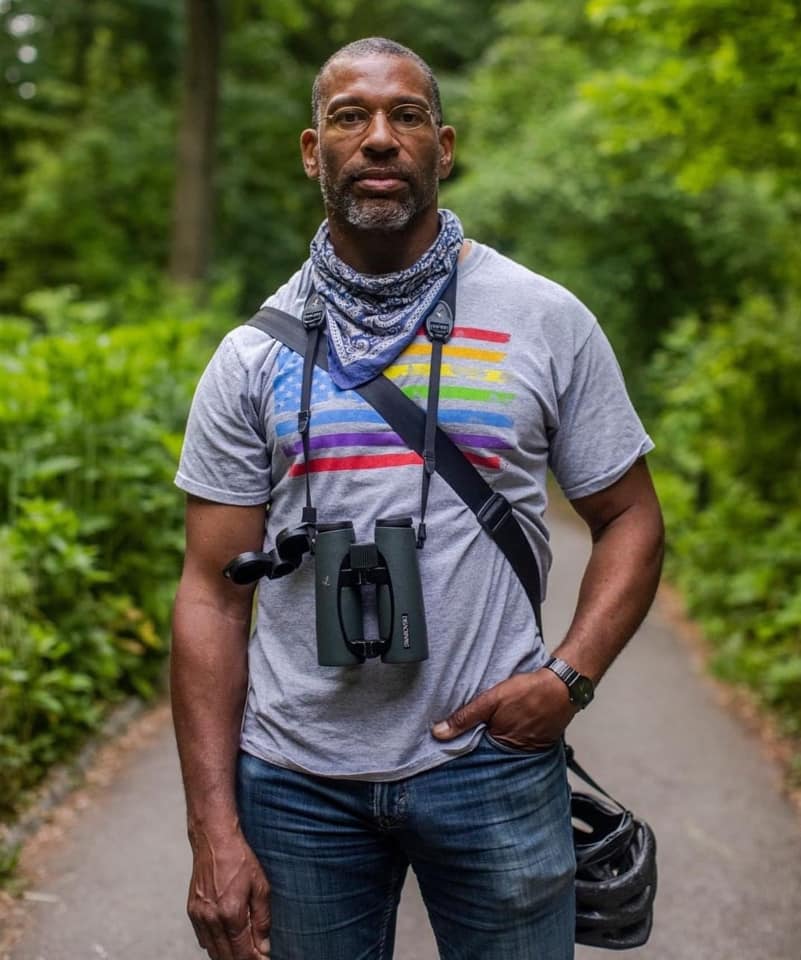

‘Being Black’ is about identity, culture, who we are inside.

This approach also gives us a hook for talking about whiteness, and presenting different types of whiteness as ethnicity. eg white australian = largely anglo celtic; vs white dutch. Same colour skin, different culture. Different ethnic identities.

It’s a standard distinction to make in feminist studies.

And the concept of ethnicity helps us talk about things like ways of moving your body or talking, which are learnt not biological.

For me the word ‘race’ is highly problematic. I really don’t like to use it.

Unless we are talking about racism specifically, and then I need that word. Racism is a specific issue: the hatred of a particular group of people for irrational reasons (eg simply because they look different or act differently). Ethnocentrism is a more complex concept. It’s about prioritising and privileging your own ethnicity and own lived experience. It can allow us to talk about anti-semitism, where a person might not look physically different, but be culturally distinct.

If we aren’t different races (or species) at at genetic level, how do we account for tropes in particular populations? For example, the overrepresentation of indigenous Australian youth in prisons? Or higher instances of diabetes in some African American communities?

This is where intersectionality gets really useful: class is the bigger factor in black women’s high infant mortality rates. Clearly, gender is also important, as it’s women’s bodies which are regulated by anti-abortion laws or subsidising abortion under public health care acts.

And there is some interesting work on the way trauma has a physical effect on bodies (with potential genetic damage). I remember reading about something to do with aboriginal women’s experiences with malnutrition + trauma = ill health for future generations. Starvation can cause genetic or inheritable damage too. And while these symptoms might be prevalent in black women, it’s not because these women are black, but because being black in modern American or Australian society means you’re more likely to experience violence (including sexual violence), poor educational outcomes, and other economic disadvantages, not to mention poor health care services.

In Australia, these latter symptoms are a direct result of racist government policies which reduce community-centred health care services and support services.

All of these points make it clear that while ‘being black’ or ‘being white’ has clear physical effects that are inheritable, these biological elements are the product of social, environmental factors. To be clear, then: we are the sum of our biology and our culture. Who we are is the result of nature and nurture. Ethnicity, then, is a more useful word than ‘race’, because it allows for variance, for the role of environment and culture.

When I say ‘class’ I’m also referring implicitly to education: women with a lower education level are more likely to have more pregnancies, to have higher infant mortality rates, to be in lower paid work, and to die younger. No matter what their ethnicity. But when you combine class markers with ethnicity and gender, you see a more severely disadvantaged group. Why do we see particular ethnic groups caught in these intersectional binds? Well, this is where the concept of patriarchy comes in handy: it helps us see how ideology (ideas about the world) and discourse (the way these ideas are communicated) shape institutions (like schools, hospitals, governments) and society.

So ‘class’ isn’t just about how much money you earn, it’s also about other economic advantages – the suburb you live in (and the services it has), the type and length of education you get, the health services available to you in the public system (which again are often worse, and over-stretched in black areas), the food available to you (see discussions about ‘food deserts’ in urban america), broken family networks (which leads to children leaving school to care for younger siblings, etc) and so on.

This is why capitalism is a key part of patriarchy, why Cierra’s point about vintage wear being ‘expensive’ is so important, and why I think it’s essential to hang onto intersectionality when we talk about race in lindy hop.