This is a very great article. It reminds me of many of my own experiences in universities. Though I tend not to be the object of sexual harassment – I tend to kick heads and take names (which is probably why I’m finding it so difficult to get a full time job now). But I have had a couple of male academics try it on with me. Once was a fellow postgrad who couldn’t seem to raise his eyes from my breasts when we were ‘talking’ (I use scare quotes because I’m not sure it’s communication when one is having trouble thinking of the other as anything other than sexualised). Another was a male academic who told a particularly offensive anecdote at a staff/postgrad party. I responded with some verbal arse kicking. And never could get a leg up in the department after that.

But recently, I haven’t had any of these experiences. In fact, it’s been about six years. I think it’s because I don’t spend so much time on campus any more. And because I’m not 21 and I’ve pretty much given up giving a fuck what pants size I wear. And because I really do kick arse and take names now, and most male academics who’d pull that sort of stunt are afraid of me. And I like that. Even if it means no one ever gives me a proper job, I like the thought of having frightened those bastards so much they avoid me and won’t make eye contact with me in the hall. And I have been known to strut upon occasion.

But I also think it has something to do with the fact that most of the academics I deal with now are women. They’re the ones running the overcrowded, underfunded, understaffed subjects I teach. They’re the ones who drop my name to people looking for tutors or lecturers or research assistants. They’re the ones who pass my name along and then introduce me and make sure people know I’m Good Enough. I think that’s half the thing – we female academics spend so much time second guessing ourselves and downplaying our abilities we forget to tell other people just how good we are. Just how skilled we are. And we hardly ever remind ourselves of our own achievements. So it’s a good thing we have each other’s backs. For the most part.

But that is a good essay. Read it, if you haven’t.

fyi, it was written by our pav.

Category Archives: academia

more rocking on

It’s no secret that I think the F-bomb is the fushiz, and browsing the internet today (mostly looking for answers for students who’ve asked me “are there any other easy things we can read about media?” – they’re sick of hearing me talk about the Media Report and so am I) I came across this article “Literature, Culture, Mirrors:John Frow responds to Simon During” in the Australian Humanities Review by the Man.

I’ve been thinking about the role of literature – or books – in cultural studies lately. Mostly, I try not to think about the ‘boundaries’ between media studies, cultural studies, book studies and (now) communications studies. They seem to be set down, for the most part, by the funding structures and course requirements of university departments and faculties and otherwise really don’t seem very useful for most of us who are actually in there getting jiggy with kultchah.

But I’d been wondering how to talk about books in a cultural studies context. One of the clearest differences in the way I think about books when I’m wearing my cultural/media studies hat(s) as opposed to the way I thought about books when I was enrolled in an English department doing ‘literature’ subjects,* is to do with audiences. I know there’ve probably been some changes in English departments since I got all into the Screen Studies (that’s what we called it in the olden days), but I’ve noticed that I think about books in terms of the relationship between audiences and textual structure rather than thinking about books as little boxes of words, standing alone there between their covers on the shelf. So while I can get all “oh, I just love blahblah author”, I’m actually far more interested in what people do with blahblah author’s work once they get ahold of the words.

So, for example, I’ve been thinking about writing a paper for a symposium being held as part of swancon. I’d like to write about watching HBO’s Big Love‘s representation of patriarchal polygamy while reading about Karen Traviss‘s matriarchal polygamies in the City of Pearl books. For me, it’s interesting to think about the way we SF fans aren’t just consuming a solid diet of SF – we read across the genre lines. And the way I think about polygamy, humanity, gender and society have been inflected by both these texts while I’m reading them both….which of course makes me want to talk about TV programming, book publishing seasons and structures of consumption, but that would be (yet another example of) digression…

This point was brought home to me the other day listening to a colleague’s very interesting paper on Scifi.com. She noted that there’d been some resentment from hardcore SF fan Scifi.com audiences about the introduction of ‘un-SF’ in the Scifi.com programming. Apparently they weren’t impressed by the wrestling shows**. Now, I’m interested in the gender implications at work there (particularly as a fair old swag – if not the vast bulk – of SF telly involves fighting, violence, warfare and plain old fisticuffs), but I’m more interested in the insistence that hardcore SF fans want only to watch SF on telly. Of course, if I were paying for an SF channel, I think I’d be after a fulfilment of my expectations – SF 24/7 YES! – but at the same time…

So I was wondering how I would go about thinking and writing about literature in a cultural studies context. I don’t particularly want to go down the fan studies track again. Yes, yes, we all know SF fans read SF books, watch SF films and telly, play SF games and party in online SF communities. But what happens when we talk about women reading those interesting romance/SF hybrid books? That’s my other pet interest at the moment – is anyone else writing about these books at the moment (not counting my posts)? And I’m definitely not interested in getting bogged down in discussions about ‘quality’ lit – if it’s a book, it’s literature to me, mate.

But anyway, back to JF. My interest was caught by this bit:

Let me offer two reasons why cultural studies has the potential to change departments of literary studies for the better. The first is that it forces students to come to terms with different regimes of value, different and perhaps incommensurate valuing processes and their relation to social forces and social positions. It shifts the interpretive gaze from a self-contained text to its discursive and social framings, within which students are themselves implicated; while at the same time it opens a potentially fruitful methodological exchange between the distinct protocols of interpretation that apply in the social sciences and the textual disciplines. The second reason has to do with process. Cultural studies supposes a pedagogy in which students are at least as fully in control of much of the subject matter as are the teachers. This isn’t the end of teacherly authority, but it does transform the learning process by challenging teachers to redefine what it is that they do in a classroom, and by involving students – in a quite orthodox Socratic manner – in the understanding and analysis of what they already know. In neither of these respects is cultural studies the enemy of literary studies; the two perhaps work best when they coexist in tension and exchange; but literary studies will not survive if it is taught as a form of religion.

That second bit is the bit I’m most interested in:

Cultural studies supposes a pedagogy in which students are at least as fully in control of much of the subject matter as are the teachers.

It’s the sort of argument that makes a great deal of sense to me when I think about teaching magazines/tabloids this semester. I never read magazines, but for the occasional copy of Nature (the glossy one), or the odd gardening or cooking mag. I don’t watch enough commercial telly to recognise the TV stars and I have absolutely no idea about mainstream, popular music. I was largely teaching this unit in reference to academic reading and a few weeks’ panicky hunter-gathering online and at the supermarket checkout (the latter proving most challenging for a hippy who likes indy grocery shops).

So while I could present the ideas to the students as academic concepts, drawing largely on my own enthusiasm for news values and news papers (hell, it’s all print media to me), we were largely relying on their specialist knowledge of and familiarity with magazines. This offered interesting moments in the tutorials, which are (of course) ten quarters female. Female students who hadn’t said a word all semester were suddenly contributing with enthusiasm. And these chicks really are magazine gurus – they read anywhere from one a week to a dozen a week. And they’re intimately familiar with the complex relationship networks which are the stock in trade of these publications.

At first we had to deal with the (mostly male) students’ disparagement of ‘trash media’. I made the point that reading these things – and making any sense of them whatsoever – required an intimate and extensive knowledge of the personalities, events and mode of discourse. We’d already talked about why tabloids are more popular than broadsheet media the week before, and they’d mentioned that ‘it’s too hard to understand what they’re talking about – the middle east is too complicated for just half an hour of news’. And I pointed out that while they mightn’t be prepared to unravel the middle east, they were prepared to wade into Britney’s social network – equally complex and foreign. Which of course led us them to the idea that personalisation is a really effective way of creating news value – making a story marketable for a wide audience.

But it was mostly an interesting exercise in the sort of stuff JF is talking about in that bit of the essay. For me, as a bub teacher, it can be both absolutely thrilling and exciting, but also terrifying. I spend most of my time worrying that I’m telling the stoods a big line of bullshit – one day someone’s going to figure out that I’m full of shit. I learnt in the very first tutorial that if you lie and pretend you know the answer to something – if you really do try and make up a bullshit answer – they’ll figure it out and you’ll look like a dickhead. So I’m all for admitting ignorance: “I dunno. I haven’t read that stuff. I’m into blahblah. But I do know blahblah writes about it. What do you guys know? What do you think?” I’ve found they’re actually far more willing to speculate and expore ideas when they’ve heard me admitting complete ignorance, but still being prepared to have a bash at figuring out an answer.

But I really like this approach to teaching – the postioning of students as specialists. And then working with them to apply the ideas from readings or lectures to explore (as JF puts it) “involving students …in the understanding and analysis of what they already know”. This was a truly fabulous approach in a media audiences subject I taught last year.

The first piece of assessment was a lit review, where the stoods chose a media audience (ie an audience of a particular media text or form) and then figured out who’d already written about it, or which bits of research could help them research their audience. The second bit of assessment involved planning a media audience research project (each week of lectures explored a different research method). It was fabulous to teach because the assessment worked cumulatively – you were building on their knowledge. The stoods dug it because they began to feel like proper media researchers – specialists with a body of knowledge and skills under their belt.

I also used tutorials to discuss media and their media interests. I encouraged them to think about the media they were into, and then as we began working on the assessment, to talk through their ideas about the research. Because we were all reading the same literature and most of us knew the media they were discussing, we could all comment and discuss the topic knowledgeably. I’ve found that this is the most important part of teaching stoods – encouraging a confidence in their own skills and knowledge. Encouraging them to trust their ideas and instincts. I mean, why not? They really, truly know things that we old sticks don’t – they haven’t read the academic literature, but they’re hard core media consumers. And they are engaged in really complex and interesting media – cross-media – consumption and use. So why not get them using those skills and ideas?

But this approach was really nice for the students – they really felt a sense of ‘ownership’ of their projects (and I used that term – our projects) and a confidence in their ideas. And they did produce some really interesting work. And man, it rocked to teach because they gave a shit and actually got excited about the assessment and readings.

I’m not sure how I got to this point, and I know this is a confusing post, but I guess this is meant to be a story about disciplinarity, about teaching practices, about methodology cross-discipline, and just another fan-atic post about your hero and mine, the Frowstah:

*I’m really sorry about this terrible sentence. I have been marking essays full of this rubbish and really can’t remember how to write any more. Perhaps I need to read more bewks?

** Frankly, it makes perfect sense to me – what could be more fantasy, speculative ficationesque than WWF?

what about this one?

Does it make a difference that Canada’s wielding a sword and not flashing her boobs?

Does it make a difference that Canada’s wielding a sword and not flashing her boobs?

I kind of have trouble with the whole judging people for grammar thing.

Yes, I like the joke, but I often think of grammar in the same way I think of manners – a class thing. So it’s really not all that cool to judge people for either…

is this wrong?

ladies making stuff: keynote=go

DFE logged this story about pecha kucha (pronounced peh-chak-cha) on faceplant this week and it’s caught my attention in a massive way. I think I want to do it. I’ve been thinking about making keynotes into little films (there’s a neat export option which automatically makes them into quicktime files) and to think that there are other nerds out there, just like me, who’re into this action… how wonderful! But of course, part of my thinking is centered on the fact that that is one hot teaching tool.

DFE logged this story about pecha kucha (pronounced peh-chak-cha) on faceplant this week and it’s caught my attention in a massive way. I think I want to do it. I’ve been thinking about making keynotes into little films (there’s a neat export option which automatically makes them into quicktime files) and to think that there are other nerds out there, just like me, who’re into this action… how wonderful! But of course, part of my thinking is centered on the fact that that is one hot teaching tool.

I’m already a really big fan of Keynote. I just LOVE the way I can combine pictures, little bits of text, little movies, music or sound files (oh yes, please – jazz up the wazoo), ‘slides’ which change automatically, or use basic animated transitions (like a page turning or one slide being pushed aside by another) and me strutting about talking crap in front of a captive audience.

I am just obsessed with the opportunities for visual puns and bad jokes – I’m still thinking I’m the queen of lecturing for my joke about laundry trucks and Roland Barthes (which I can’t really tell here because it takes some setting up).

Writing that lecture about the media and war, I was also struck by the possibilities of keynote for making quite full on emotional points.

I really enjoy making these things (even though they’re a lot of work), and I think they’re a really effective way of teaching – the stoods like them and stay interested, and I find they slow me down and stop me talking a zillion miles a minutes (which I tend to do otherwise). Not to mention the fact that when you’re teaching media it actually helps to show some.

I really enjoy making these things (even though they’re a lot of work), and I think they’re a really effective way of teaching – the stoods like them and stay interested, and I find they slow me down and stop me talking a zillion miles a minutes (which I tend to do otherwise). Not to mention the fact that when you’re teaching media it actually helps to show some.

I also like the ‘found object’ approach to keynotes that I’ve been taking. Basically, I write my lectures in a word file, including all the necessary information, then I break it down into ‘slides’ (which usually means one major point per slide, so I’m looking at about 70-90 slides for an hour and a half lecture), then I go looking for images and clips. Hello google, my fine friend. And hello youtube. Once I’ve found clips, I download them and then insert them into my keynotes. Because I’m using a mac, it’s all a matter of click-and-drag: easy peasy.

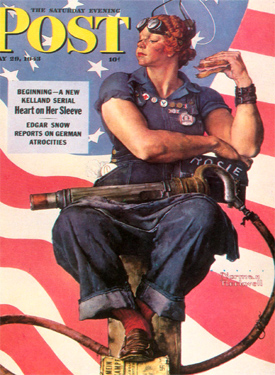

I’m also a fan of sound files – I’ve found some truly fabulous audio files from the www.firstworldwar.com site. There’s one I especially like called ‘Loyalty and German-Americans’, which is a speech by the American James W. Gerard speaking in 1917. It’s a neat example of wartime racism, making quite clear the idea that the media is a useful place for developing anti-enemy emotions, including dehumanising the enemy. And it’s particularly effective when you match it with a series of posters like this one from WWII.

I’m also a fan of sound files – I’ve found some truly fabulous audio files from the www.firstworldwar.com site. There’s one I especially like called ‘Loyalty and German-Americans’, which is a speech by the American James W. Gerard speaking in 1917. It’s a neat example of wartime racism, making quite clear the idea that the media is a useful place for developing anti-enemy emotions, including dehumanising the enemy. And it’s particularly effective when you match it with a series of posters like this one from WWII.

I’ve just dropped that sound file of that speech into my keynote so the stoods can hear exactly how people talked about this stuff. The fact that most of them are first or second generation Australians (if that!) makes Gerard’s anti-German immigrant talk extra pertinent. Talking about WWI is interesting because we don’t have cinema or TV or radio working in the same way as it was in WWII and then later wars – we’re looking at a culture dominated by visual print media and public speaking.

And of course, when it comes to WWII, I just have to play songs like Ellington’s A Slip of the lip (can sink a ship), because it illustrates so perfectly the sentiment in posters like this one and this one.

And then, of course, I show them pictures of the current war-time, racism-inciting, ‘anti-terrorist’ posters like this one*.

A slightly different message: talk more about the things you see, rather than talk less, but still inciting a sense of paranoia and mistrust of the people around you. Or more specifically, mistrust of the people who are ‘unusual’ or ‘not like us’ around you.

Looking at all these amazing posters, and watching the doco Hype yesterday (which I picked up for a few dollars in the recent JB sale – ah, serendipity!), I’m suddenly all inspired to print my own posters. I’m not sure whether I’ll be promoting kick-ass chicks in sensible clothing or punk-ass indy rock, but I can be sure it will be wonderful. Though I’ll probably have to get ducky to tell me how…. when I get time, of course.

*My favourite line on that poster is this one: “I know this person who has downloaded a lot of documents from suspicious websites”. I’m just waiting for one of my stoods to ring up our Fearless Leader and dob me in.

responsibles

Firstly, here’s a picture from this week’s lecture. We are all about celebrity this week.

Firstly, here’s a picture from this week’s lecture. We are all about celebrity this week.

I have about a million emails in my inbox from panicky students, all asking me if their ads are ok for the assignment. The assignment is due next week. I also have a bunch asking for extensions, for reasons ranging from ‘I just haven’t had time’ to ‘I’m sick’.

I’m not sure what to do about them all, so I’m ignoring them.

The “can I have an extension because I haven’t had time” excuse is a tricky one. One of the challenges of working with students who are supporting themselves financially with shitty jobs while they study, or who have families they’re supporting, is that they’re not on campus terribly often, and they work shitty jobs for the other 4 days a week they’re not at uni. What do I do in this situation? On the one hand, part of the assessment task is being able to manage your workload. On the other, these guys really are working shitty jobs that leave them zero wiggle room – they really can’t ditch a shift just to do an assignment. And it’s not like they’re slacking – I’ve noticed more and more students are having to work crappy jobs to fund their university study. And as I move down the food chain, away from the sandstones and down to the concrete slab unis, I find more and more students have less and less time for wandering around the library making friends with librarians or just popping in to see me to talk about assignments.

I think about the university of Melbourne’s new ‘American model’ uni, where degrees are reworked to become postgraduate degrees, and I shudder. It’s hard enough for students like mine to support themselves on bullshit jobs for the three years of an undergraduate degree. But to then put themselves through a postgraduate degree that doesn’t offer a nice, fat scholarship… it’s really a matter of access and equity.

Oh well. I’ll answer their emails tomorrow.

did i say unbelievable teaching tool already?

So I’m doing a lecture on the media in war time.

I start with WWI, then WWII, then Vietnam, then the Gulf War and finally the ‘war on terror’.

It’s been heavy going, to say the least.

I’ve collected a lot of images from the intertubes, and also some absolutely amazing footage.

I’ve found some really great sites like www.firstworldwar.com, which has some truly awesome AV and sound files, which I’ve just been popping into my keynote presentations. Keynote rocks, by the way – a truly fabulous alternative to powerpoint. So much easier to use. So much prettier.

I’ve also been playing on YouTube. Search for ‘second world war propaganda’, and you get fascinating archival footage – news reels, animations, etc.

Do a search for ‘vietnam war footage’ in YouTube and you get a stack of archival footage. And some truly freakin’s scary red neck racist commentary.

I’ve just started into the bit on the Gulf War and the ‘war on terror’, and that’s scary. It’s really upsetting. The Gulf War is easier to deal with because I’m discussing the way it was sanitised by CNN – lots of talk about technology, lots of computery stuff. Not a lot of bodies.

But the stuff on Afghanistan is really breaking my heart. One of the points I’m making is about the way the internet has suddenly allowed anyone to upload footage of the conflict – US soldiers, local citizens, politicians. I’m also writing about blogs and the US army sites, but the stuff that’s really caught my attention is the way ordinary people are using youtube to make little films.

It really reminds me of the stuff I’ve read about community media and the role of media in developing countries… if you have a camera phone, you can make a movie. And if you can get access to the internet, you can put it online.

I know that getting online isn’t easy, and that supplies of electricity are difficult, but still. This is really a massive, massive change in the way wars are represented in the media. And more importantly, the way people in occupied or invaded countries represent themselves.

One thing I have come across is Alive in Baghdad. I’ve only just stumbled over it, but it’s interesting. I know nothing about it, and part of me wonders about anti-US propaganda. But I suspect it’s on the level. Does anyone know?

pimping out cultural studies rock stars

Writing these lectures this semester, I keep coming back to a couple of questions.

Should an undergraduate course present an ‘unbiased’ overview of a particular area of research? In other words, if you’re teaching an introductory media or cultural studies (or gender studies or political science or whatever) subject, should you present an overview of the highest profile thinkers in the field – even if they contradict each other?

Or should you present a subjective overview of the literature and thinking which you find most convincing, which presents a cohesive overview of a particular group or genealogy within the literature or which best represents the theoretical approach of your particular university?*

If only it was that simple, though. I’ve been also been wondering if an intro subject should present an overview of key thinking within a specific national context – Australian media studies, British media studies, American media studies…?

If you answer yes, then, of course you’re also left asking “well, shouldn’t I include some of the American (or Australian or British) stuff just as an example of how we don’t do things here?” Or perhaps you’re wondering if it mightn’t be kinda neat to include some work from Indian or Asian scholars…

On the CSAA list recently some of the contributors argued that we have a responsibility as scholars to raise our students’ awareness of the various ideological assumptions at work in John Howard’s intrusion into rural indigenous Australians’ affairs. On the one hand, I agree entirely, in part because it seems the ‘right thing to do’, but also because it seems the sort of thing that Stuart Hall would approve of. In other words, cultural studies has its roots in social activism (sort of), and issues of class and ethnicity and gender and sexuality have always been at its heart (well, for some people. Some cultural studies kids have decided that that stuff’s so last millenium). In this approach, then, you not only outline the various thinking at work in cultural studies, you present it as it if was ‘true’ or at least workable or something to aim for.

So, for example, when I outline concepts like ‘patriarchy’ (in a discussion of feminist textual analysis), I don’t present it as an abstract concept, but as a real context and ingredient in the texts we’re reading and in our lives.

Don’t get me wrong – I do agree with these concepts. I do firmly agree that patriarchy needs discussion (and dismantling?), that we should be getting very angry (or at least very active) about Howard’s policies, that we should be thinking critically.

It’s just that I wonder whether I should be teaching these things as if they were all ‘true’ (ie from a ‘biased’ perspective), or ‘objectively’, as if they are ideologies we should engage with and discuss, but not necessarily believe.

Part of me also worries if this is an entirely arbitrary and bullshit line of thinking. I wonder if it’s even possible to do a decent job teaching cultural studies (and gender studies and so on) if you don’t present them subjectively. I mean, that’s kind of what they’re about.

If I do attempt an ‘unbiased’ approach, am I not simply obscuring or ignoring my own personal beliefs about the world and politics and preconceptions? And if that’s the case, what the fuck am I doing calling myself a feminist, if I’m prepared to pretend that an objective approach is possible anyway? I spend three quarters of my time telling students that objective approaches aren’t possible – that we’re steeped in culture and that to really do ‘fair’ analyses we should begin by addressing (and stating) our own ideas about the world and how they affect how we read and write and think and talk about culture.

I wonder if this is part of the problem of tertiary education.

Teaching first years basic concepts like active readership, I say things like “Meaning isn’t an inherent and static quality of a text, but made through readers’ interaction with it” and “There is no single ideology or idea about the world, but multiple and competing ideologies” and adopting an approach in the classroom which explicitly emphasises the idea that ‘every reading (or opinion) is important and valuable’ so that students feel comfortable speaking up.

With this in mind, it seems logical to rework assessment to make it more achievable for students with ‘special needs’ (which is all of them – whether they have reading problems, aren’t comfortable with English, have to work two jobs to feed their families, care for elderly relatives or whatever), and to use a range of teaching tools and approaches in lectures and tutorials to meet the needs of such a vast range of learning styles and students’ needs.

But at the end of the day, the arbitrary marking system necessarily involves being unfair and making it very clear that not every reading style and every ideology and every mode of self expression is valuable or worthy. In fact, the entire marking system, the tutorial/lecture/assignment structure is constructed to encourage and valorise a particular approach to knowledge, a particular way of learning and teaching.

Teaching ‘inclusively’ (ie practicing what I’m preaching in a cultural studies subject) seems like holding back the tide. Fairly fruitless at best, self-deception at worst.

To this point I’ve been taking a mixed approach. I present particular ideas as if they were ‘true’: “patriarchy is…” rather than “some believe that patriarchy is…”, and, when the students ask, I clearly state my own ideas and beliefs. I don’t think it’s possible to canvas every ideology in just twelve weeks, so I present the ‘good ones’. I don’t think first years are really up to being presented with competing ideas (they’re still learning how to learn – getting over that ‘just memorise what I tell you’ thing and moving towards ‘what do you think about what I’ve told you? Do you agree? Why not? Why?’), so it’s best to present a more consistent approach. I also think we should be teaching Australian cultural studies – using Australian readings and ideas. With exceptions for obvious people (like Stuart Hall, who had such an impact in Australia)… but is that just cherry picking?

I wonder if perhaps we should think of the people teaching these subjects as resources in themselves. Not just a pair of legs for walking ideas past the students. We should regard their ideas and work as resources, and expect them to teach those ideas – to bring that** – when they’re in the classroom (whether they’re in front of 200 or 10 students). Which is really why I think that the very best and most experienced teachers should be teaching first years. …and why I think we should have the very best teachers teaching beginner dancers too, btw.

But in both dance and acadamia, teaching beginners or first years is seen as grunt work, the lowest status, least important teaching. Crowd control. The stuff we can farm out to pgrads for guest lectures or get in sessional staff to teach, rather than getting the most experienced, highest profile staff involved.

Which is a very great shame, because it’s a great opportunity to reach a very large number of students all at once, to fire their enthusiasm for the area, and to – if we’re thinking like those CSAA doods – actually encourage critical discussion of the culture we’re actually living in.

I also think it’s a shame that experienced staff take the least interest in these large introductory subjects. I know I’m only new to this, and probably don’t have a clue, and will change my mind as I get more experience, but aren’t these the most important students in the university? They’re harder to teach because they aren’t familiar with universities, and they don’t know any of the basic stuff that eventually brings them to more complex research of their own. But they are the people who have new ideas and fresh and unjaded. They don’t know what media studies is like. So if you come in swinging, using enthusiastic teachers who have mad teaching skills, really love what they do (and what they’re reasearching), surely that will spill over and infect the students (to mix a metaphor)?

And if the people teaching these subjects are also doing their own research, teaching first years will keep them in touch with the basic, fundamental work in their field. If the people doing this teaching are also the big names in publishing and research, won’t their enthusiasm for their work also be infective?

This semester, half the readings on the course are by people who taught me in my first year subjects at UQ – Tony Thwaites, Lloyd Davis, Graeme Turner, Frances Bonner, John Frow, etc etc etc. They’d teach subjects in their special areas, but they’d also be our tutors in first year, and they’d do one-off lectures in their speciality area. So we saw and heard and worked with these guys up close.

Now, when I’m teaching these first years, crapping on about how great Graybags is, I realise that these guys are just names to the students. They have no idea why Graybags is neat as a person as well as as a researcher. So they don’t really care.

I try to make these guys more than just names for the students – I always use photos of them in my slides, and I try to add in interesting details to keep their attention (I love the story of Roland Barthes for this sort of talk). If I’m talking about uber scholars like the Frankfurt School doods, I describe their social context as well, and how that might have influenced their work. I make sure I show a picture of Stuart Hall and tell them that he wasn’t born in Britain.

And I hope that helps them be interested in these people. But really, it would be far easier if Stuart Hall was standing in front of them telling them the story of how he got into talking about media.

This is an introductory subject, so half the job*** is selling media studies to them, making them want to learn more. So it has to be interesting. They have to care. They have to see how they could contribute to the area, how their ideas and experiences are important and worth talking about. And if that means pimping out cultural studies rock stars, so be it.

*Which is, of course, one of the reasons why it’s important to be researching while you’re teaching, and to have decent collegiality happening in your department.

**The Squeeze suggested the students might laugh less in my lectures if I lay off the ghetto talk. I reject the idea: I am totally street.

***The other half is skilling them up with some basic methodological and theoretical tools.

Textual analysis? √

Feminism? √

Cowboys? √

you know you’re in the right job when…

You get to say things like this:

“There has been no final and conclusive research to support this particular idea of ‘media effects’ – there are no definitive studies showing that watching violence on TV does turn you into a serial killer (which is kind of unfortunate because I like the idea that watching Alien and Terminator 2 will make me a superhero).”

Accompanied by these two lovely Ladeez on a giant screen.

I guess the interesting part of this particular segue involves some sort of discussion about the point of diversity in representation – if effects theory is crap (and that’s a bit of a long bow I know, but I’m making a dramatic point here), what’s the point of agitating for, well, female action heroes?

Teaching this semester I noticed (putting together a lecture on cowboys) that there really haven’t been any seriously arse kicking mainstream action film chicks since the 1990s. Where are the Linda Hamiltons, the Sigourney Weavers of the 21st century?

Are we, like totally over that now?

Please don’t tell me that all we’re left with are (literally) Invisible Women who really only seem up for defensive tactics and getting really really upset.

And hey, why the fuck isn’t Sue Storm the boss of the F4 anyway? She has the best name, she has the most versatile superpowers, she’s totally the boss of annoying people like her brother Johnny… Maybe if she had some sort of serious responsibilities she’d quit obsessing about her wedding and actually have something challenging to occupy her (supposed) super-scientist brain.

Do I need to talk about superhero costumes? I’m as much a fan of the hawt body action as the next red blooded sistah, but I’d kind of like to see some overalls like Siggy’s or perhaps some mucho extremo body armour c/o Aliens.

[deep breath] But, as I was saying, it is way neat to be able to actually talk about this stuff with students. And preparing all this lecture material is really reminding me of the pretty radical roots of media and cultural studies. I’ve been hanging out with swing dancers so long I’ve forgotten that it’s actually way uncool to just accept bullshit gender stereotypes and perpetuate that whole ‘boys look after girls, girls look pretty and shut their mouths‘ crap.

Today I choose to wear full body armour and decimate the patriarchy.

(Hand over that phallus to someone who knows how to use it, motherfucker – the sistah has some multi-tasking to do).

John Frow = fushizzle

The paper that made hardened ackas cry like babies has been on my mind for weeks now… hell, since December last year when I heard the Fushizz give it (or bring it, depending).