A discussion came up on the facey the other day about how leads can deal with rough follows. It caught my eye, because I’d just had a dance with someone the night before which was particularly rough. I was leading, and the follow really moved herself through steps in a fierce way which left me feeling a bit sore. It also dovetailed nicely with my ongoing thinking about how to prevent sexual harassment in lindy hop.

On that last topic, I’m approaching this with a different strategies:

- Developing a clear code of conduct for behaviour

– (in progress) - Teaching in a way which helps women feel confident and strong, and provides tools for men looking to redefine how they do masculinity.

– using tools like the ones I outline in Remind yourself that you are a jazz dancer - Teaching in a way which encourages good communication between leads and follows.

– I am keen on the rhythm centred approach as a practical strategy. Less hippy talk, more dancing funs.

– I like simple things like talking to both men and women about being ok with people saying no to you. - Developing strategies for actually confronting men about their behaviour.

– I talked about how I do this in class in Dealing with problem guys in dance classes

– I am totally ok with telling men to stop pulling aerials on the social floor because it’s a clear ‘rule’, but more ambiguous stuff is stumping me

– I’m trying to figure out how to do it in other non-class settings

– I’d like to find a way to skill up men so they can do this stuff too; ie it’s not just women’s jobs to deal with men sexually harassing women.

I seriously believe that feminist work needs to be practical. High theory and abstract conversation is very important, but for me pragmatic feminism means actually doing things. It’s important because it powers me up and makes me feel strong, but it’s also important because you know – actually DOING something. It can be quite hard and scary sometimes, because you are agitating, you are disturbing the status quo and you will attract some shit. Men don’t like to be told they’re doing dodgy stuff (and lefty men get particularly upset by this), especially when it’s a woman telling them. They often respond with physical intimidation, which is scary. And there can be social consequences for women which suck in a social dance community like lindy hop.

So, for me, I try to do this work in a way which isn’t too confronting or frightening for me. And which isn’t too confronting for other people. Feminism by stealth.

Where does Frankie Manning fit into all this?

Just in case you’ve been living under a rock (or are just new to lindy hop), Frankie Manning was one of the best dancers, choreographers, and troupe leaders of the swing era (1930s-40s). He’s generally positioned as ‘second generation lindy hop’, and credited with inventing the first public air step with his partner Freda Washington.

More importantly for modern lindy hoppers, he came out of retirement in his 60s to ‘teach us how to dance’. He taught people to lindy hop from the 80s until he passed away at 94 in 2008.

He wasn’t (and isn’t) the only old timer to do this. But most significantly, he had a very joyful, accessible approach to dancing, he didn’t mind that we all sucked, and he was prepared to work with complete amateurs, even though he really didn’t have any experience teaching total noobs or of teaching in a formal classroom context.

So Frankie holds a special place in many modern lindy hoppers’ hearts, and many of us take his example as near-gospel.

There are a range of problems with this approach, and I talk about them in Uses of history: a revivalist mythology. I basically say that I think we should be wary of uncritically using Frankie and his approach when we teach and talk about lindy hop. There are a host of political issues to consider when we appropriate his image and approach, both in terms of race, ethnicity and class, but also in terms of gender. Basically, he wasn’t perfect, and we have to be careful we don’t literally use him and his work for our own ends. And we have to be careful about how we use historical discourse in our classes.

So that’s my disclaimer, really: the next bit of this post is written with an awareness that I am a white, middle class woman writing in a developed, urban city in the 21st century. I am taking the words and teaching of a black, working class man of the early 20th century and using them for my own ends. I try to couch that with respect to Frankie’s memory, by name checking him and giving him credit for his work. I direct students to footage of his dancing, and to his own words.

I also make it clear that I am framing his work from my own POV and goals as a teacher and dancer. I didn’t know Frankie, and I only met him a few times and learnt from him a few times. So I tread lightly in his memory, and I try not to speak for him. But I am inspired him – by his dancing, by footage of his classes, by the mark he left on dancers who I learn from now and admire very much. I try to work with respect for his memory and for his work; he is an elder in our community, a custodian of knowledge, and important.

So here is something I wrote on the facey.

It’s about how I ‘use Frankie Manning’ in class to counter misogyny and sexism and to promote a type of connection that privileges creative collaboration, mutual respect, joy in dancing, and flat out badarse dancing.

I have trouble with rough follows every now and then. Especially ones who’re in troupes or do a lot of performing. They’re used to really physically strong leads (I don’t have the upper body strength of a man). I’ve had some bad shoulder and back twinges lately, despite my best efforts to improve my own technique, core stability and so on. As with dealing with rough leads when I’m following, I figure a rough follow is a partner who isn’t listening or paying attention to me because they’re stressing. At least I hope that’s what it is – it’d break my heart if rough follows were deliberately rough.

So the first thing I do if my partner is a bit rough, is to get us in closed position and tell a joke. But not too close a closed position, especially if they’re a woman who’s obviously weirded out by dancing with another woman. I’ll try to do something to distract the follow from being fierce and doing what they think I’m leading. Once we’re both chilled, and paying more attention to each other, I do super simple steps with a lot of emphasis on jazz feels and call and response – they do something, I echo it. That helps us both get on the same page. Then I build it out from there, adding in open position, etc etc.

So my first response to a rough follow is to become a really clear, yet incredibly gentle, responsive lead. And I make my basics the very best I can, so they feel confidence in me.

I’ve been using Frankie Manning as a good guide for safe dancing lately when I’m teaching. He would usually teach from the lead’s perspective, so I find it very helpful as a lead working to make a dance with a follow really comfortable and nice.

That means I’m emphasising:

– Looking into your partner’s face.

This is the most important thing I know about lindy hop. LOOKING into your partner’s face. It was the one big thing I learnt in the Frankie track at Herrang last year (where all the classes were taught by people who’d worked closely with Frankie). Once I noticed it, I was stunned by how infrequently partners look into each other’s faces.

It’s good for your alignment and posture relative to your partner, but it’s also good for making you connect with another human as a person, it helps you learn to observe your partner and recognise when they feel pain/scared/happy and it’s good for making you lol.

-> follows are less likely to throw themselves through steps if they’re looking at your face and seeing you flinch in pain. They’re also distracted from the move by the genuine human connection, so they stop pre-empting or rushing or panicking.

– Call and response rhythms as fun steps.

They make you pay a LOT of attention to your partner, visually and physically, so you can ‘hear’ what they’re doing rhythmically. This is good for interpersonal communication (how is my partner feeling?) and learning how to recognise physical signals (what does a suddenly-tight arm tell me when I combine it with their facial expression?)

-> this is the next level of looking at your partner. So follows stop pre-empting and are really there with you. And because you’re really listening to them (everyone calls, everyone follows), they feel like you’re listening to them, so they feel more confident and worry less about ‘getting it right’ and rushing or hurting you.

– Your partner is the queen of the world.

We say this a lot: your partner is the queen of the world (whether they’re leading or following, male, female, whatevs). This means that you have to look at them (and we model how to be impressed by/respond to your partner positively), and the ‘queen’ should then feel confident enough to bring their shit.

This teaches you to be connected emotionally with your partner, and to recognise how your positive response to a partner’s dancing can make them feel good and then bring their best shit.

-> follows bring incredible swivels and generally become the queen of the world. They pay more attention to you as a lead, and they feel like you’re really listening to them, so they reciprocate.

– Scatting.

Brilliant for improving your dancing, but when your partner is scatting, you can hear them, so you’re connected with them in an additional way.

-> makes follows lol.

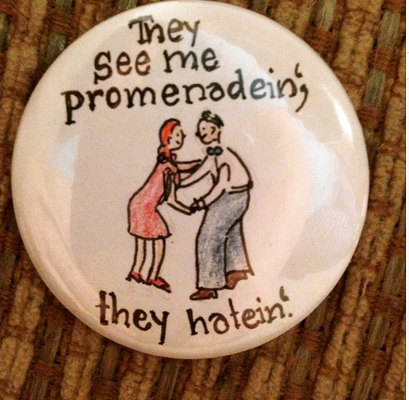

– Frankie thought the most important lindy step was the promenade*.

It’s in closed position, it requires lots of communication to walk together without kicking each other, and it has lots and lots of variations with lots of different emotions. It teaches you to communicate with someone, and you have to look into each other’s faces a lot, and be ok with that.

You get to hold someone in your arms, which means you have to be respectful.

*Lennart says so, so it’s probably true :D

-> I find some follows aren’t so ok with being so close, so I have to pay really close attention to them to find the ‘comfortable’ distance/connection. This makes me do my very best dancing. I try to put me in front first, so the follow feels more comfortable (follow first means they’re walking backwards – eeek!). I do pecks to make them lol, or rhythmic variations. I respond to the variations they bring.

– You’re in love for 3 minutes.

Doesn’t have to be romantic love. But for that 3 minutes, this person is the most important person in the world. You look at them, you lead steps you think they’re like, you do your best to realise the step or move their aiming for, you work to make this dance work.

To me, this is excellent mindfulness. It makes it hard to be rough with your partner. And when someone is feeding all those good vibes back at you, you smile and do your very best dancing.

-> follows become the queen of the world. They listen to you, and even better, they bring things to the dance.

I think it’s worth looking at a video of Frankie teaching to see how he did this stuff:

Frankie Manning’s Class part 2

I don’t think his approach is 100% excellent. He does drive the class, he uses gendered language, etc etc. But he is the ‘star’ teacher, and his teaching partner partner is his assistant – this is very clear. He uses gendered language because he is explicitly thinking about male leads and female follows, and his talk about respectful dancing uses this gendered dichotomy. I’m not excusing this, I’m pointing it out. And here I can make this point: while I dig a lot of what Frankie is doing in this video, he’s not perfect, and I actually find that reassuring. He wasn’t a saint, he was a real person, and when we idolise dancers, we need to keep that in mind: we don’t excuse their faults because we love their dancing.

A couple of things I like about this class:

at about 4.44: “If you find yourself falling, and he does not stop you from falling…. take him with you.” I LOLed when I heard this. But it’s a nice, simple way of saying ‘look out for each other!’ and reminding women that they aren’t passive objects here.

11.48: Frankie tackles inappropriate contact “Fellas, don’t take advantage…. we are just dancin’”

Nuff said, really.

With all this talk about Frankie, I think it’s worth pointing out:

When you watch footage of younger Frankie (ie in his 60s, and 20s), he seems quite ‘rough’ or ‘strong’ compared to modern dancers. Is this in conflict with this ethos of mutual respect in lindy hop?

(photo credit: I found this pic via an image search on google, and it’s hosted by Swungover, but chrome crashed and I couldn’t find the page again! argh! So I don’t know who the photographer is!)

This is a tricky one, but I think it’s where we’re really done a disservice by the lack of attention to the original women lindy hoppers who danced with Frankie teaching us today. I suspect that women followers were a different breed too. When you watch historic footage, you see that they fiercely took space, and matched their partner’s intensity. So Frankie might have had a partner who was confident enough to take space, and to be a little less submissive and a little more determined to shine.

I have no evidence for this, and it probably reveals my own lack of dance knowledge and skill. But I’m wondering if we need to have a look at old footage in a new way. I’m thinking of the way Janice Wilson used to talk about Ann Johnson, and the fierceness of her swivels. And of course, you have to think of Norma Miller when you think about fierce women lindy hoppers.

At any rate, this brings us back to the idea of how we might use history when we talk about lindy hop partnerships. And I have no real, final answers, of course, just a bunch of poorly practiced ideas.