This is a post about Duke Ellington and dance, because he is on my mind at the moment.

I’ve recently discovered the 1951/52 stuff by the Johnny Hodges band on this dodgy digital download album Pound of Blues is really great for teaching dance, particularly choreography which recognises strict phrasing. It’s good, solid stuff, and I’ve used it for DJing in the past, though not with any particular enthusiasm. The steady, predictable phrasing of songs like ‘Wham’ on this album do not really reflect all of Ellington’s compositions, as anyone who’s tried to choreograph to ‘Rockin in Rhythm’ will know. But Johnny Hodges was, of course, a musician who played with Ellington for a long time. One of the soloists the band leader would compose for, and organise compositions around rather than forcing them to fit into a musician-shaped hole in his band.

I’ve recently discovered the 1951/52 stuff by the Johnny Hodges band on this dodgy digital download album Pound of Blues is really great for teaching dance, particularly choreography which recognises strict phrasing. It’s good, solid stuff, and I’ve used it for DJing in the past, though not with any particular enthusiasm. The steady, predictable phrasing of songs like ‘Wham’ on this album do not really reflect all of Ellington’s compositions, as anyone who’s tried to choreograph to ‘Rockin in Rhythm’ will know. But Johnny Hodges was, of course, a musician who played with Ellington for a long time. One of the soloists the band leader would compose for, and organise compositions around rather than forcing them to fit into a musician-shaped hole in his band.

I’d like to say that this ‘Pound of Blues’ album reminded me of the orsm of Ellington, but that’s not true. Ellington is always on my mind. I love him. I love his music and I own a lot of it. A LOT. I’m a massive fan of the Ellington small group stuff, but I’m also nuts for the bigger bands.

The Never No Lament: the Blanton Webster Band 3CD set was one of the first serious Ellington CDs I ever bought (though it was a lot cheaper then than it is now), and I bought it because dancers and DJs I admire recommended it on the SwingDJs discussion board. It’s great, but as with many of the Ellington recordings I have, the quality isn’t so great. There’s a lot of surface noise (ie scratchy crackly rubbish) and the high pitched stuff sounds awful when I’m DJing. And all that from a CD.

The Never No Lament: the Blanton Webster Band 3CD set was one of the first serious Ellington CDs I ever bought (though it was a lot cheaper then than it is now), and I bought it because dancers and DJs I admire recommended it on the SwingDJs discussion board. It’s great, but as with many of the Ellington recordings I have, the quality isn’t so great. There’s a lot of surface noise (ie scratchy crackly rubbish) and the high pitched stuff sounds awful when I’m DJing. And all that from a CD.

This last point is important, because I recently bought myself another Ellington set, Decca’s Complete Brunswick and Vocalion Recordings 1926-1931. I’d somehow managed to miss this little chunk of Ellingtonia and I needed to rectify the problem. I went with CDs rather than the cheaper downloads because I’m finding download files – especially legit ones – are of such poor quality they make the songs unDJable. The rubbish files plus the scary sound quality of the recordings themselves are just unuseable on shitty sound systems.

I guess I do have kind of an Ellington problem. But then, he’s so interesting, he justifies a little obsessive collecting.

I used to have a long bus commute to uni which I’d spend reading my way through Gunther Schuller’s book The Swing Era: the Development of Jazz 1930-1945 and listening along with my whole Ellington collection on my ipod. I read music (haltingly), and Schuller spends quite a bit of his time examining scores in detail. I’m not entirely convinced by everything Schuller says, but Schuller’s is an interestingly scholarly approach to a musician who was as comfortable with concert halls as dance floors.

I used to have a long bus commute to uni which I’d spend reading my way through Gunther Schuller’s book The Swing Era: the Development of Jazz 1930-1945 and listening along with my whole Ellington collection on my ipod. I read music (haltingly), and Schuller spends quite a bit of his time examining scores in detail. I’m not entirely convinced by everything Schuller says, but Schuller’s is an interestingly scholarly approach to a musician who was as comfortable with concert halls as dance floors.

Today’s dancers are familiar with many of the soundies and film fragments featuring Ellington’s band. Mostly because they also featured dancers. The most famous of these is probably Hot Chocolate (Cottontail), with Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers:

My favourite is Bessie Dudley and Florence Hill dancing to Ellington’s band playing ‘Bugle Call Rag’ in the 1933 film Bundle of Blues:

Bessie Dudley was married to Snake Hips Tucker, and she appeared with him in Ellington’s 1935 film Symphony in Black. There’s a scene in that short film where Tucker’s character throws Billie Holiday to the ground, and you can’t help but think of the verisimilitude – Tucker was a brutal, violent man who abused Dudley.

Ellington’s relationship with dancers was strong and complex. He worked extensively with dancers at the Cotton Club and on film, and travelled with Dudley and other dancers on tours. And later, as his music became more complicated and challenging, his productions with dancers and choreographers like Alvin Ailey also became more challenging.

There’s an interesting article by Patricia Willard called ‘Dance: the unsung element of Ellingtonia’ (Australians can read the full text version here, but there are other versions available online if you google). In that article Willard writes

Duke thought and spoke in dance vernacular. Maneuvering a remarkably stable roster of assertive, quirky, occasionally aggressive individualists into a consistently identifiable and cohesive big band through the decades demanded an accomplished psychologist and master manipulator, which he was. He proudly referred to his role as “The Choreographer.” (Willard)

This idea of Ellington’s music as dance music (which Willard pursues in that article) is nice. Ellington himself said “Swing is not a kind of music. It is that part of rhythm that causes a bouncing, buoyant, terpsichorean urge.” (Ellington, quoted by Willard) This idea that Ellington was at once engaged in popular culture and able to move on to all that difficult artier music and concert dance is just one bit of proof of his versatility.

Most of my love for Ellington is centred on his earlier stuff and on those small group recordings. My interest tends to wane at about 1950, to be honest, but that’s not a strict rule. There’s a song called ‘B Sharp Boston’ which Ellington recorded in 1949 and which used to get around on those dodgy ripped compilation CDs as ‘Sharp B Boston’. I picked up the Chronological Classics Duke Ellington Orchestra 1949-1950 CD in about 2006, and discovered it was actually called ‘B Sharp Boston’, and that there was a bunch of other great stuff on that CD that makes for top DJing (I’ve written about this before in Duke Ellingon’s Difficult 1949-1950 period). ‘Joog Joog’, for example, is one of my favourites (I like to pair it with Doris Day singing ‘Celery Stalks At Midnight’). A fair chunk of stuff on this CD is, however, already edging over into dissonance and confusing timing which makes for challenging dancing.

Most of my love for Ellington is centred on his earlier stuff and on those small group recordings. My interest tends to wane at about 1950, to be honest, but that’s not a strict rule. There’s a song called ‘B Sharp Boston’ which Ellington recorded in 1949 and which used to get around on those dodgy ripped compilation CDs as ‘Sharp B Boston’. I picked up the Chronological Classics Duke Ellington Orchestra 1949-1950 CD in about 2006, and discovered it was actually called ‘B Sharp Boston’, and that there was a bunch of other great stuff on that CD that makes for top DJing (I’ve written about this before in Duke Ellingon’s Difficult 1949-1950 period). ‘Joog Joog’, for example, is one of my favourites (I like to pair it with Doris Day singing ‘Celery Stalks At Midnight’). A fair chunk of stuff on this CD is, however, already edging over into dissonance and confusing timing which makes for challenging dancing.

These sorts of awkward combinations of note and timing really heralds bop. But years ahead of other peeps. Listening to even Ellington’s 30s stuff, you hear a hint of the dissonance that was to come. I tweeted the other day “It’s like Ellington heard collective improvisation in NOla jazz and went “hm. Dissonance.” In 1938.” And @twobarbreak replied “Look where all of Ellington’s players were from, and who they learned from. your hunches closer to right on than you think!”

Again, though, it’s fascinating that Ellington could produce excellently danceable songs like ‘B Sharp Boston’ and ‘Joog Joog’ at the same time as he was really getting into much more experimental stuff. By the end of the 40s Ellington had well and truly begun to explore crazy arse stuff that doesn’t always work for dancing. Well, unless you’re Ramona and Todd at ILHC this year

I read an interesting blog post recently (cannot remember where, I’m sorry – PLEASE let me know if you know the one I mean), where someone cleverly pointed out a couple of recent lindy hop choreographies that worked with this sort of ‘difficult jazz’. One of them was Giselle Anguizola and Nathan Bugh’s 2011 Classic Lindy entry in ILHC:

I keep an eye on Giselle, because she’s been involved in some interesting projects over the years, from Girl Jam to working with jazz bands on the streets of New Orleans. Both are interesting, not just as exercises in jazz dance and jazz dance skills, but in the enculturation of dancers in jazz tradition.

One of the things I really like about the way dancers like Giselle and Chance engage with bands on New Orleans streets is their recognition of turn taking. Soloists in a band take turns, even (especially) the vocalists. In these street jazz groups, the dancers function as soloists, taking their turn, and then stepping back to let the musicians shine. They’re not only responding to the music they hear, but also functioning as part of the band, and part of the performance. Most modern lindy hoppers barely manage to look up and see the band they’re dancing ‘to’, let alone take a moment out to admire what they hear.

And of course, all this talk of New Orleans jazz, solos and recognising individual talent within a collective ensemble takes us back to that idea of Ellington’s most radical work being a response to the interests of the musicians in his band, many of whom were from New Orleans or taught by New Orleans musicians. The most radical ‘art’ part of Ellington was perhaps his references to tradition and vernacular, everyday culture?

Other things about Ellington and dance I couldn’t fit in this piece of writing:

- My new favourite ILHC 2012 clip, Melanie and Joshua in the Lindy Hop Classic category dancing to Ellington’s 1941 version of ‘Jumpin’ Punkin’s’:

-

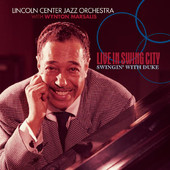

The Lincoln Centre Jazz Orchestra’s album Live in Swing City: Swinging with Duke.

Probably the most overplayed, most popular, excellent modern big band swing album. Recorded live with a crowd of dancers, this album features the most accessible of Ellington’s work, and is an excellent gateway drug for new dancers interested in discovering swing music. - Todd Yannacone again, this time with Naomi Uyama dancing to Ellington’s ‘Main Stem’ in about 2006:

References:

Willard, Patricia, ‘Dance: the Unsung Element of Ellingtonia” The Antioch Review, 57.3 (Summer 1999): p 402

Schuller, Gunther, The Swing Era: The Development of Jazz, 1930-1945, Oxford University Press: USA, 1989.

My husband is obsessed with Ellington. I think at least a third of our charts are Ellington, at this point.

That was a good read. And thanks for putting Giselle & Nathan up. Ha! Dancing to bop, it’s not an easy flavour, the more I enjoy it when it is done. Many state that it was the end of partner dancing (lindy). I’m in no position to disagree with valid arguments. But my gut feeling doesn’t want to accept that statement. Besides it’s too smplistic, it is still music that makes you want to move, just listen!