I don’t really understand why this had to be an animated gif series, but it’s cool.

Chimamamda Ngozi Adiche, We Should All Be Feminists

(cyberteeth, via carrionlaughing)

I don’t really understand why this had to be an animated gif series, but it’s cool.

Chimamamda Ngozi Adiche, We Should All Be Feminists

(cyberteeth, via carrionlaughing)

It’s 14*C here, but it feels 7, which is VERY COLD for Sydney. I hate the cold, which is why I didn’t like living in Melbourne, where the lindy hop is better, but the weather is not.

Sydney is beautiful. It is that city you see in the tourism ads – beautiful beaches a short city bus trip from the CBD. It has all the culture stuff Melbourne does, only people in the galleries and bars and music venues are wearing thongs or tshirts and their scarves are affectations not necessity.

I really don’t have much to write about right now. I’m a bit busy – got a few events to run (three at last count), classes tonight to prepare for, practice tomorrow to think about. But I do have a new CD or two. I saw lovely Leigh at Unity Hall on the weekend and he gave me his band‘s new CD ‘Australiana’. It’s not danceable music at all, which is really quite nice.

My copy of the Midnight Serenaders‘s new CD ‘A Little Keyhole Business’ arrived, and it’s not so great, which is disappointing. I reckon their second album is the best. But they’re a fun band, and I bet they’re superfun live, so it’s nice to support them.

I’m waiting on a CD or two from a Very Famuss Musician to arrive. Their publicist asked if I wanted one, and I assume she wanted me to review it or talk it up or whatevs. I’ll write a review when it gets here, and we’ll see what it’s like. I have to say: there’s nothing more exciting than a Very Famuss Musician you admire asking if they can send you a copy of their CD. Even if it is their publicist asking.

[Meanwhile, I’m listening to the New Sheiks’ new CD ‘Australiana’ right now, and it’s so very good. I had thought about writing a post about the way I/we listen to music across genres, and how musicians play across genres, and how that’s important, but I don’t have the brain for it right now.]

The little red counter on my email icon keeps ticking over. People are responding to the storm of emails I sent out yesterday. I’d finally gotten it together after a couple of weeks of dodgy health, and did some admin work. Working those contacts. The biggest part of my workload is maintaining contacts. With musicians, with venues, with other event organisers, with sound engineers, with visiting (or possibly-visiting) dance teachers, with local dancers, with artists and designers… there’s really a lot of leg (and mouth) work to be done. Lots of people to talk to and telephone and email. And nothing’s harder when you’re feeling a bit rough than getting it together to have a sensible conversation with someone you don’t really know.

I’ve stopped reading a lot of the blog posts and bits and pieces discussing gender in the lindy hop world. Mostly because most of them aren’t terribly good. I don’t think everyone should learn to lead and follow. But I do think every lindy hopper should be able to solo dance competently and confidently. You can draw your own euphemism if you please. I don’t see the point in arguing for women leads. If you can’t accept the fact that women are as competent leads as men, then you probably don’t know much about lindy hop. Or men and women. And you aren’t worth my time. Women should just lead if they want to. The end. I reckon it’s more important for the male leads to realise just how much better most of the women leads around them are, and lift their game. More importantly, particularly in scenes with fewer leads than follows, the male leads need to get up off their arses and lift their game: the women dancers around them are so much better than they are, they’re turning to solo dance out of desperation. Desperate for a challenge. In sum, the best way to maintain the heteronormativity of lindy hop is for men to be really fucking good leads. Right?

No, I’m not convinced either.

I haven’t done a heap of DJing lately. The Roxbury, one of Sydney’s only proper dancer-run lindy hop events has folded forever. Sad times. That was my favourite DJing venue. There’s still Swing Pit, but I quite liked having an event I could go to and have no responsibilities – just turn up late if I wanted, dance as much as I wanted, leave when I wanted. And if there was a problem with the sound, I didn’t have to fix it.

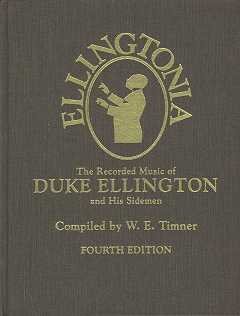

I did buy a copy of Ellingtonia, the Duke Ellington discography. It’s great, but the format of each entry is kind of annoying – instead of listing each musician by name, their initials are used. This sucks, because it means you have to flick back to the guide to figure out who’s who. Makes sorting your music collection really tedious. But then, I think it was hand-typed. It’s certainly self-published. So typing out every name would’ve been a bum.

Duke Ellington, aye. Just when I think I’ve gotten over him, I hear something new, and he draws me back in. I’m really enjoying him in 1941 atm. Again. My current favourite songs is ‘Goin’ out the Back way’ from ’41, which I heard a DJ playing in a smallish dance comp somewhere in the states or Canada. It’s the perfect lindy hopping song. Which of course is the perfect solo dancing song.

Solo dancing has really changed my perception of tempo and speed. Nothing’s too fast when you’re dancing on your own. Which I guess relates to the challenges of following: when you follow, you can’t really change the ‘speed’ or ‘tempo’ at which you and your partner are dancing. The lead gets to decide how many steps you both take. Whether you swing out like crazy people or just step gently through some nice rhythms. When you dance on your own, you get to decide everything. But this has also informed my leading lately. And I’m simply not a terribly talented follow. I would quite like to be a brilliant follow, but it just doesn’t gel for me. How even does following work?

Perhaps my biggest problem while following is that that I just forget I’m not leading, and I introduce steps or rhythms which are ignoring what the lead is doing. And that’s not cool, whether you’re leading or following. So, you know. Leading. That’s where my brain is at. I actually think that you have to decide whether you’re a lead or a follow, if you really want to level up your dancing.

Sure, you can do both and that’s cool. But if you want to get really good at one, you have to dance that one exclusively for a while at least. Because there’s a significant part of your dancing which isn’t conscious decision making. It’s an unconscious response to what’s going on. When I’m leading, I’m responding to what the follow is doing (where their weight is, the tension in their body, the shapes they’re making, the rhythm or timing they’ve got going on), and I respond by initiating something that develops their theme. When I’m following, respond by responding. Sure, I can bring my shit, but someone has to lead, and someone has to follow. They’re different roles, and particularly when you’re dancing at higher tempos, you gotta have a clear idea of who’s doing what. This opinion could really just be an expression of aesthetic preferences: I like to see a clear lead and follow in a partnership, not a muddied, blurry mutual exchange. Not because of politics, but because of physics and biomechanics. And rhythm.

Lennart Westerlund says this thing: “yes, you have the steps, but you do not have the rhythm. I cannot see the rhythm.” He said this about a million times while he was here, and eventually someone in a small teachers’ session asked him “Can you demonstrate the difference? I don’t understand what you mean by ‘see the rhythm’.” So he danced a phrase or two where the rhythm wasn’t clear. Then he danced a couple of phrases where it was very clear. It was quite stunning: I felt all my muscles jump and leap in a real, physical Pavlov’s lindy hopper effect.

So when I watch someone dancing, I don’t want to see a sort of vague blurring of steps. I want to see the rhythms, the shapes, the transfers of weight. I don’t just want to see which foot a dancers weight is on, I want to be able to see which part of the dancer’s foot is on the ground, and whether or not their weight is committed to that particular part of the foot. I want to see muscles recruited efficiently, and turned off when they’re not needed. I really want to see a nice, swinging timing. And I want to feel that leap and jump in my own muscles as I watch. So, I guess I want to see someone lead, and someone follow. I don’t care if you’re taking turns in each role during the dance, but you can’t both drive. Someone has to lead, someone has to follow. Doesn’t mean the follow isn’t also contributing (and I’ve gone into how in detail before). Means that you’re doing lindy hop, which prefers requires participation from each dancer.

Lennart says that too: “someone is leading and someone is following.” I don’t think he cared who was doing what (if he did, he was tactfully discrete with his opinions :D ), he just wanted to see a lead and a follow. But Lennart also made another lovely point: “I don’t want to be speaking all the time. That is boring. I want to hear what my partner has to say.” All of that is of course wrapped up in his phrase, “We must make friends with the music.” What a lovely thought: that we come together, as partners, through friendship with art and the creative work of other people.

HIPPIES!

To be honest, I’m still working through the concepts Lennart Westerlund introduced me to in May. Was it only two months ago? But Lennart’s relaxed, gentle approach to rhythm and timing has changed my brain. He could be dancing very simple, gentle, relaxed figures, but stuff them full of highly complex rhythms and timing. It’s a fabulous idea, and it’s something I’ve been thinking about for a couple of years, and which guides the content of our classes. I’m sure the more ‘intermediate’ dancers find it terribly boring and naff – they just want ‘new moves!’ when I’m thinking ‘moves shmooves – give me an outline and I’ll fill it in with far more interesting stuff.’

I’ve noticed that the very best lindy hoppers in the world (the Swedes, and Skye) tend to use a lot of quite simple figures, but their timing is supremely complex. And that complexity is dictated by the music. People like Ellington. ‘Rockin in Rhythm’, your phrasing is so difficult. Yes, they do use complex moves as well, but the fundamental assumption of good lindy hop is that a simple shape (a swing out, a tuck turn, a circle) is also something highly sophisticated if you make it so.

The thing I like about this relationship between simple and complex, is that these guys looks so relaxed when they dance. Everything they do looks easy. Until you try to reproduce it. There are quite a few dancers around at the moment who are quite fabulous, but their dancing looks so overwrought. They look like they’re Working. So. Hard. I want it to look so easy; I think ‘oh, I can do that’ and then I try, and realise that it’s not humanly possible. And of course, the relationship between ‘simple’ and ‘complex’ is a little like the relationship between ‘hot’ and ‘cool’. I’ve written about that a lot, so I won’t go into it again. Except to say, that the most important part of lindy hop is being relaxed in your body, until you need to turn a muscle or muscle group on, then that part of you is on.

I think that this is part of what makes the ‘swing’ happen. Don’t rush. We’re not rushing. We’re cool. We’re not hurrying. It’s uncool to hurry.

I didn’t mean this post to become a big spiel about dancing. I’m doing a LOT of reading at the moment. Stacks and stacks. I’m on GoodReads as dogpossum if you want to talk books. One of the things I am reading more of at the moment is comics. I’ve always been a bit of a low-level fan, but I’m frustrated by how quickly they read. I need more bang for my buck – at least more than an hour from a book.

I’ve been reading Wonder Woman lately, particularly the Gail Simone series starting with The Circle. LOVE.

I quite like the New 52 Wonder Woman

And I REALLY like the New 52 Batwoman. The art is just gorgeous.

I wasn’t struck on the New 52 Batgirl (boring).

But of course, the new Ms/Captain Marvel is THE BEST EVER.

And I am totally on this bandwagon:

I’ve also been reading Saga, which I quite like, but I’m just not a Vaughan fangirl.

I’m a fan of trade paperbacks because individual comics just don’t last long enough. And, to be honest, I find the writing in a lot of comics that I’m reading jus doesn’t come close to the good SF that I read. And I read a lot of SFic and SFant.

But Wonder Woman. She’s the best. Especially when she’s drawn by Cliff Chiang.

Writing this post, I realise I’ve heaps more books and music and television too talk about! But I have things to do.

…so if you want to talk about Hemlock Grove or Teen Wolf or The Fosters or The Returned or Top of the Lake, assume I’m interested!

(image: “Ultracrepidarian: A person who gives opinions and advice on matters outside of one’s knowledge” from The Project Twins’ A-Z of Unusual Words)

I reckon this post about dancesplaining is good stuff. I like the way Jason expands the idea of mansplaining. Mansplaining is about power, and dancesplaining is about power. I like the way Jason has expanded the idea of explaining-as-power. He’s making the point that this act of power isn’t about biological sex, it’s about social power. This seems to be something that a bunch of commentary on sex and gender in dance getting about at the moment doesn’t seem to grasp.

In other words, while we might associate particular characteristics or qualities with masculinity or femininity (eg violence or aggression or technical know-how might be associated with masculinity in anglo-celtic discourse), they aren’t actually biologically determined. Men aren’t naturally aggressive or violent or good with tools (lol) because they have a bunch of testosterone or a dick or a brain wired in a certain way. Men often demonstrate violence or aggression or are the first to have a go with a tool because the society they grew up in encouraged them to be that way.

So mansplaining isn’t biologically determined, it’s an act of power, where the person explaining assumes they know more, and assume they have the right to speak/explain. When this explaining person is a man, explaining something to a woman, they’re often taking advantage of the fact that women in this same cultural context are brought up to be ‘polite’ and to avoid confrontation. That means avoiding interruption or telling an explainer that they already know this stuff. Avoiding conflict can also be about helping other people save face (and avoid embarrassment or loss of face/status). Many women help men save face to avoid conflict because in their experience conflict can often involve physical conflict: an angry, embarrassed man can be a violent man.

Danceplaining and mansplaining isn’t often malicious or deliberately dictatorial. It’s usually an unconscious demonstration of discursive power. Just as a man mightn’t stop to worry about whether that guy who just got on the train is about to sit next to them and make suggestive comments, a man who explains mightn’t stop to think about whether he should shoosh. In both examples, men have lived with the experience and idea that they will be safe on public transport, that they won’t be harassed, and that it’s ok to explore or explain their thinking out loud. Both of these public behaviours are about status, power and confidence in public space. They’re both also about the power of feeling safe enough to explore a new idea in front of other people.

If you want to have a bit of a read about the ‘mansplain’ concept, I suggest starting with Rebecca Solnit’s piece ‘Men Explain Things to Me: Facts Didn’t Get in Their Way’.

I like Jason’s piece because makes it clear that explaining – dancesplaining – isn’t necessarily about gender. While men might do it it women a lot in class, women quite often return the favour and explain to men why they’re doing things wrong. But I do think it’s about power, and I’d argue that certain types of power can be gendered (or associated with a particular gender identity) in certain contexts. So dancesplaining is often perpetrated more by men, and as most dance classes have more men leading than women, we see more leads/men dancesplaining to follows/women than vice versa. I’d probably add that a male lead teacher should be particularly careful not to paraphrase and repeat a point his female follow teaching partner has just made in class settings. That’s a type of mansplaining too.

Jason extends this thinking to explore how this type of behaviour in class affects the way we might think about leading and following generally.

I’d argue that dancesplaining (as a gendered behaviour) works with other gendered behaviour to create a continuum of gender and patriarchy. This is how discourse and ideology work: if it was just one little thing that bothered us (and we could fix with a quick solution), then feminism would be redundant within a couple of hours. But patriarchy is complicated. This is why I have troubles with the recent posts about ‘sexism’ on Dance World Takeover: the thinking is too simple, and the solutions are too simple. A reshuffling of ideas about connection isn’t going to magically solve sexism in a community. It might be one point at which we can engage with particular ideas about gender and power, but tackling that one thing this time will not quickly or easily ‘solve’ patriarchy.

If we are to engage with gender in the lindy hop world in a constructive way, we need to think about all sorts of stuff: clothes, notions of ‘beauty’ and ‘strength’, discussions about food and ‘health’, teaching practices, competition formats (eg how is a jack and jill competition judged, and how does this process articulate ideas about gender?), the role of solo dance, the place of aerials, how we manage and think about injuries and pain, ethnicity and race and how we think and talk about it in dance, talk about sex and sexuality in dance partnerships, labour relations and the role of ‘volunteers’ and unpaid labour, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera. Gender: it’s complicated.

This is why, though, I’m quite pleased by Jason’s piece. He takes one behaviour (or use of language and power), and then draws out the effects and related behaviours and thinking within a culture (and cultural practice). I’m especially delighted by the way he presents his own thinking and behaviour. This really is what I would call being a feminist ally. Doing feminist work. I am also very pleased by the way this thinking makes clear that feminist work can also be socialist work, and also be the work of pacifists and human rights activists. Feminism might be centred on gender, but we can’t talk about gender without also talking about economics, ethnicity, sexuality, violence, and so on.

I was especially delighted by this paragraph in the ‘establish permission’ section:

Both as a teacher and as a student, I have found it is often really helpful to approach first with a question along the lines of “Can I make a suggestion?” If he or she says “yes,” then we can proceed to having a discussion about it. If he or she says “no,” then I keep my opinion to myself unless that person is causing serious harm (in which case I might have led with something more direct like “I need to talk to you”). The act of asking for permission can feel a tad cumbersome but it respects the other person’s boundaries and gives them a moment to adjust to a state of readiness to hear feedback. It is the dance class equivalent of inviting someone to a performance evaluation rather than barging into their office and telling them they need to shape up or ship out.

I think this is a gorgeous illustration of how undoing the power dynamics (and hierarchies) of pedagogic discourse in dance can work to undo other dodgy power dynamics in a dance community. The class is, of course, where we socialise new dancers – where we teach them not only how to dance, but how to be in a dance community. It’s something I need to remind myself: though I might be a teacher, I don’t automatically have the right to correct someone’s dancing in class. And how I should correct them needs to be carefully thought about, to promote and encourage mutual respect.

If you’re curious, I’ve written other posts where I’m pretty much annotating the development of my ideas about teaching. I’m only new to teaching dance and boy am I making a lot of mistakes.

– Dealing with problem guys in dance classes: where I write a huge, long, rambly post exploring my ideas about this, and nut out some strategies.

– Self Directed Learning: where I look at alternatives to the formal dance class, and how this might destabilise hierarchies, and also complement traditional learning models.

– teaching challenges: routines, structure and improvisation in class: where I remind myself that rote-learning is about power and hierarchy, and not in the spirit of lindy hop.

– Teaching challenges 2: drilling and memorising: kind of like that previous post, but with some dodgy referencing of pedagogic lit.

– Valuing the process rather than the product: where I talk about a bunch of things, but most importantly, about the importance of being wrong and making mistakes.

Catherine Redfern answers in her 2003 piece ‘Feminists are Sexist’: Should feminists have to spend exactly half their time, energy, and resources working on behalf of men to be taken seriously? Catherine Redfern thinks not.

…sadly, this “improving women’s lives is sexist” attitude reflects part of the wider mainstream fear of feminism. It’s why people say things like ‘I’m not a feminist, I’m a humanist’ or ‘I’m not a feminist, I’m in favour of human rights’. It’s because there is a stigma attached to any activism that unashamedly benefits women, as a social group. It’s not seen as worthy enough, and fighting on behalf of women as a group is embarassing somehow. I’m just talking about plain, uncontroversial activism that improves the lives of women.

I do feel as though many of the people reading my blog simply don’t have a working understanding (or even a basic understanding) of the central tenets of feminism. There are lots of places to find out about this stuff, so it’s really in your interests to do a little research before you wade into a feminist debate. I mean, just banging on about ‘reverse sexism’ makes you look like a fool. The best place to start is with Feminism 101. I’m also quite fond of Thinking Girl’s brief overview of key terms in feminist thinking.

The bit about oppression is useful in dismissing this ‘reverse sexism’ bullshit:

Something else that is important to understand is that oppression is not discrimination. Oppression is about systems and relations of power, and exists in social structures and institutions. Oppression is wide-spread subjugation of one group while simultaneously privileging another group. This means that those groups who are subjected to oppression are not in a social position to oppress people belonging to the dominant group. There is no such thing as “reverse” sexism, racism, homophobia, (dis)ableism, classism, etc.

Basically, ‘sexism’ is an articulation or demonstration of power. So it’s something that people with power get to do. In the context of gender and sex, patriarchy (which organises our societies) robs women and girls of power. So when a woman* calls you or your friend out on your dodgy thinking or behaviour, she isn’t speaking from a position of power. She’s actually taking a bit of a risk, and she’s speaking against the grain. In this sense, feminism is activism because it is critiquing the dominant social order.

Conservative media and politicians might bang on about ‘political correctness’** and argue that feminists are oppressing them, but this is patently untrue. If you take a quick look at the stats, you’ll see that most property is owned by men, the highest wages are earned by men, women are more likely to be sexually assaulted, most positions of power (political, economic, industrial, religious…) are occupied by men. So, yeah, feminism. Not really fucking over the patriarchy just yet.

*This is why I think it means something quite different for men to speak out about sexism and misogyny. I’m not sure how I feel about the idea of ‘male feminists’. I much prefer the concept of ‘feminist allies’, because I think that one of the most important parts of emancipation and social power is being able to speak up for yourself – to represent your own ideas and self in public discourse. And while I love and adore and admire men who speak up for feminism and feminist projects, I think it means something quite different when a woman is standing up. The concept ‘feminist allies’ excites me. It tells me that men are ok with working with women; they don’t need to lead the charge.

This topic is quite fraught, and one that many feminists disagree about. So my opinion is just one among many. And of course, when you start talking about gender identity, transgender identity, and so on, this distinction between ‘men’ and ‘women’ stops being useful. I haven’t done a lot of thinking about this, though I SHOULD.

**I do recommend reading up about the history of the term ‘politically correct’. The Wikipedia page is surprisingly useful. Basically, the people who use the term ‘politically correct’ are usually people who don’t like the idea of feminism or socialism or other actions or movements which are interested in equity and social justice. Not too many feminists use the term. I don’t use it because it’s just not useful: it implies that there’s just one way of pursuing social justice, when of course feminism is about diversity and plurality of approaches and thinking.

This is another post I wrote ages ago, but didn’t bother posting it because I’m feeling pretty paranoid about the nasty responses my ‘feminist’ posts get. As though any post I write could not be feminist.

Anyways, a quick timeline: I first read about Frumious Bandersnatch’s post ‘A Feminist Lead’s Manifesto’ via Lindy Hop Variation’s For Followers’ post ‘Reactions to the female lead’s manifesto’. I read that post and thought ‘aw yeah, whatevs.’

Then I read the actual manifesto (which an awful lot of people on Faceplant didn’t seem capable of doing – they just waded into that response piece, instead of actually reading the original manifesto. I facepalm and I facepalm.)

I read it and thought ‘cool, a manifesto’. But I didn’t have time to reply, because I was busy being a female lead, a teacher, an event manager, etc etc etc. Too busy fighting the patriarchy to write about fighting the patriarchy.

This draws me to a discussion of the role of women’s studies as critical thinking vs feminism as activism. I remember an essay Nancy Fraser wrote about the importance of activism to feminism, arguing that theory is important, but the essential nature of feminism is to enact or work for social change. So, in other words, just talking and thinking and writing about it isn’t enough. I’ve just spent ten minutes trying to find the reference to the article, partly because there are some problems with Fraser’s position (or, more likely, of the way I remember that position), but I can’t find it. GODDAMM it. Anyways, the general point was/is that while theory and discussion is very important to feminism, activism – actually doing things is far more important. You can of course argue that thinking and talking about things does constitute activism (particularly in regards to language and power, but Fraser has things to say about structuralism and linguistics which I can’t go into here).

I’d argue that writing and talking about dance is important. The mediated experience of dance (particularly in terms of youtube videos reframing actual dancing) can be just as powerful – and is probably more pervasive for most people who don’t dance every day – than the actual dance act. But I feel, quite strongly, that talking about dance, eventually, has to give way to dance itself in terms of actual authority. In other words, it ain’t what you say about lindy hop, it’s the way that you do it that counts.

In my experience, if I really want to change things in the lindy hop community, I need to get out there and do it. Less talk, more action. The best way to get more women leads on the floor is to have women leads on the floor. And we gotta start somewhere. Someone has to be that first woman out there on the dance floor, leading. And fuck, I’m ok with being that first person (I took up this point in greater detail in I vant to be alone and lindy hop followers bring themSELVES to the dance; lindy hop leaders value this).

I do also think that it’s important to encourage other women to lead. That can mean just cheering when they’re rocking something on the social floor, asking them to dance yourself, or it can mean saying things like “Fuck, yeah, just get out there and have a bash” directly to them. And you don’t need to use activist or political rhetoric in this sort of encouragement. Really, leading is fun – so encouraging other people to have fun isn’t really a difficult project.

Despite this commitment to actions, I still think it’s important to think about things and to write about them. Because critical engagement with a topic is important. Off the dance floor, we have time to think about things, and to look for connections. We can look for the way systemic disempowerment – patriarchy – works. This is the nature of patriarchy: it is a complex system of actions and institutions and discourses and face to face activities.

If I feel so strongly about the importance of thinking and writing about gender and dance, why haven’t I written much lately, in a concentrated way?

I have to pause here for a diversion. But it’s a relevant one. I have to talk about the current Australian political climate (Edit: here is a list of articles with more information). When the ‘Female Lead’s Manifesto’ was written, the first woman prime minister of Australia was the target of a sustained, furious hate campaign by the mainstream press and conservative politics, which eventually resulted in her being ousted from the leadership of the ALP (and hence the prime ministership). Anne Summers has written lots of interesting things about this, and I’ve heard Kerry-Anne Walsh’s book ‘The Stalking of Julia Gillard’ is a good overview of this whole issue.

If you’re a person with even half a brain, you’ll be furious about the way Gillard was treated, whether you agree with her actual policies or not. The misogyny, the hatred has been palpable. It’s been a scary time to be a woman in Australia.

So let’s return to the Female Lead’s Manifesto. The author is Australian, and I think that you’d have to have no media contact whatsoever to have missed the horrid shit happening our media sphere. So this manifesto was written in a particular moment in Australian political and social history. Let me spell it out for you: if you were living in Australia, consuming Australian media, you would have clearly received the message that ‘women leaders are fucked up, bad, and awful.’ …not that this is unique for women leaders in any patriarchal country.

Do I go too far in reading lindy hop ‘leads’ as ‘leaders’ in the same way that a PM is a leader? No. No. No. Leaders decide policy, followers enact that policy. The lead is the PM, the follower is the government. Two different types of power. It is a fairly stretched point, but I think the theory is the same: there is a sense in both dance and political discourse, that the ‘natural’ state of things is for men to lead and women to follow. Hence the resistance to using gender neutral language in dance classes: it is as though teachers cannot even imagine that women can be competent, serious, focussed leaders. So language needn’t change to reflect this idea: that women lead.

Let’s get specific. How did I feel about the Female Lead’s Manifesto? Generally, I thought ‘ah, this is a manifesto. It is a personal statement of intent. It is for this woman, to rally her reserves. It’s not exactly as I would have written it. But then, it’s not my manifesto.’

Faced with the creeping, dragging weight of patriarchy in dance, we all need a little pick me up now and then. So even though it’s not my manifesto, I’m still excited by it. It lifts the spirits.

Let me really get into it, now:

Frumious Bandersnatch makes this clear at the beginning:

Fuck the heterosexist patriarchy, I’m a female lead and I’m not making excuses for it. This post is not a list of reasons to validate the existence of females leads, this is a manifesto.

Yes. This is thrilling. I am not making excuses. I am not validating. I am telling you HOW IT IS.

This is exciting. For a woman to simply state, with no prevarication or excuses, how she feels, is exciting. And for this statement to be such a rallying call! Such a provocation! She’s not apologising for having ideas! She is DECLARING!

This is what a manifesto should do. It is a declaration of ideas and intent. This is HER declaration of HER ideas and HER intent. Speaking it makes it so.

The second part is more challenging. This is the really provocative part:

This manifesto starts with the premise that most leads are men and most followers are women. When we first start dancing we are usually not given a functional choice – even if we are told that women can be leads, we see that the vast majority of women are followers. There is overwhelming pressure for us to be followers too, especially when we’re new and just beginning. I will even go so far to say that all female leads know how to follow to some degree.

How exciting! Yes, I agree with the first sentence. And the second. Not the third – I know women leads here in Sydney who don’t follow, can’t follow, will NOT follow. This is hardcore. I am so impressed, so envious. They are much fiercer than I am. Much stronger in their convictions. This is exciting.

…but here is where I need to pause. What does it matter that I agree or I disagree? This is not a call for discourse, or an invitation to conversation. This is a MANIFESTO. In this piece, the author is REMAKING THE WORLD. How exciting!

Why don’t I just play along? Why don’t I just accept it as read, that women are better leads than men? Why can’t I just pretend. Or at least accept the premise of this scenario. What would the world look like?

IMAGINE:

a world where women lead better, more, than men.

Imagine a world where most cops are women, most judges, most politicians. IMAGINE!1! It’s just so exciting, just so revolutionary and destabilising a thought. And it’s exciting because it is so far from my lived reality. It will not happen in my lifetime. And that is why it is exciting: it is forbidden, unlikely, subversive, transgressive, revolutionary. REVOLUTIONARY.

And that is because the inverse is true.

I don’t think most men stop and think… heck, most women don’t stop and think about the fact that most positions of power are occupied by men in our society. No, biology has nothing to do with it. My uterus is not preventing me from running the world.

Now, here’s a truly radical thing: gender switch the main characters in CSI. Of your news readers. Of your school teachers. Of your bus drivers. Imagine! Just the thought is making me giddy. Everywhere: women being and being portrayed as publicly capable and competent, and more important – being respected and treated as capable and competent! FUCK!

Now, pause. If you’re Swedish or Danish or generally from a more progressive country, this won’t rock your world. But here, in my country, this is our first woman national leader. This is amazing. AMAZING. This has NEVER HAPPENED BEFORE, in two hundred years of white history. This is THE FIRST TIME a woman has been the leader of my country. Finally, there’s someone like me being powerful and competent in public.

So when the Female Lead’s Manifesto is written, it is saying, not ‘imagine’, but IT IS SO. Who are we to disagree? How do we know this isn’t true? Sure, you might have anecdotal evidence to the contrary, but what if it’s true generally? This is mind-blowing thought. And why not – why can’t we just accept this? Why can’t we imagine the impossible, the improbable, the unlikely? If it feels revolutionary to imagine half the women in your scene leading, then how revolutionary is it to imagine ALL of them leading, and being BETTER at it than men! It’s mind-blowing!

And if you won’t – why not? If you can’t – what’s wrong with you? Why can’t you imagine women being better than men? Can’t you let go of your assumptions about gender, that somehow men are always going to be better? Every day patriarchy asks us to accept that all men are better leaders than women, that more men lead than women. And even though most of the time we have no clear statistical evidence to support this claim, we just accept it.

I’m not saying we have to enact this gender switch. Or even believe it. But why can’t we just imagine women this way? What does this imagining do to the way we see the world? This make-believe stretches our brains. It broadens our horizons. We’re jazz dances. We do the impossible every day! We create the amazing every time we move! Jazz dance is ALL ABOUT revolution and radicalism! So what’s stopping us?

Because, every single day, we are expected to accept that a woman can’t be as good a prime minister as a man. That a woman can’t lead as well as a man. That a woman can’t run a business as well as a man. Every single day, every moment of my life, I’m being told – by everything around me – that I am not as good as a man at leading. And I’m supposed to just accept this and treat it as normal. EVERY SINGLE DAY I am being treated by everything around me as though I am an object to be ogled, there for the desires of any man who may want me. EVERY SINGLE DAY I am being told that I am in danger, and that it is my own fault. EVERY SINGLE DAY my leading on the social dance floor or as a teacher or in competitions is made unusual, remarkable, strange, unusual, radical, unnatural. And I’m not even running a bus, let alone a whole country! If I can’t be trusted with these decisions, how can I be trusted with the whole country?!

So what I want to know, is not whether you agree with the Female Lead’s Manifesto, but WHY aren’t you furious about the fact that I am being told – all the time, by everything around me – that this Manifesto is a lie? That ONLY men can lead?! And that ALL men are necessarily better leads than women!?

WHY aren’t you jumping to your feet in rage when people tell you this?

My question is not “why are you angry about the Female Lead’s Manifesto, but why ARE YOU NOT angry EVERY DAY about the things that women are told by our culture?” If you can’t imagine that a woman can do one part of a dance, how can you possibly begin to imagine that a woman could be prime minister or drive a tank or perform surgery?!

Just as importantly, why AREN’T you enraged that men make up so few of our follows? What’s wrong with following? Why don’t you want it as badly as you want leading?

Apparently men are supposed to be ok with the idea that they shouldn’t want to follow/wear a dress/be associated in any way with femininity.

Finally, I need to tackle just one piece the ocean of stupid that flowed after the Female Lead’s Manifesto. Someone asked about the piece (inevitably, stupidly, painfully), “Isn’t that sexist?” and I’ve heard a variant “Isn’t that reverse sexism?”

No, friends, this isn’t sexism. You must remember: we are not starting from a level playing field. We are living within patriarchy, where everything is loaded in favour of a select special interests group within our community: white, heterosexual, middle class, able bodied men. This minority holds the majority of power, of money, of resources, of public space, of media space. Sexism is dependent upon context. It is a relationship of relative power. I don’t have time to spell it all out for you, so I’ll just redirect you to Feminism 101, where someone with more patience explains things to you.

The most annoying part of patriarchy is that it has convinced you – us – that this is normal. That it is an inevitable consequence of biology or divine intention. That women are not 51% of lindy hop leaders because we have a uterus or too little testosterone or too little body hair.

Understand this (for this is how it is): women are not 51% of lindy hop leaders because some fuck has told us we’re not capable of it. Some fuck has made it harder for us to lead than to follow. Someone has made it easier for us to follow and for men to lead. I am being deliberate about intentionality here. Don’t just accept that ‘society makes it so’ or that the reasons are ‘too complicated’. My being afraid to post a comment on gender in dance isn’t complicated. It’s fucking simple. IT IS SIMPLE.

So you need to look at simple solutions. YOU. Assume that there are things that you can do, and that these aren’t complicated. Start small. Start with things YOU can do.

So ask yourself: are you that person telling women they can’t lead? When you stand up in front of a dance class, are you making it easier for women to follow and men to lead? Gender neutral language is such a tiny, small thing. Why haven’t you taken it up? What’s wrong with you? You’re a fucking JAZZ DANCER, man, of COURSE you can use gender neutral language!. I mean, there are a million other things you could be doing to improve the ratio of female:male leads in your scene. Who rotates in your classes – leads or follows? How many female leads do you have teaching? How often do you reference women dancers when you talk about dance history? Do you know who Norma Miller is? Do you stop yourself saying things like “It’s traditional for women to follow and men to lead?” If you don’t, what’s wrong with you – that statement is untrue!

What are you doing to make your lindy hop scene a more interesting place? Remember, if only 0.4% of your women dancers are leads, then you are robbing your scene of the other 99.6% of women who may consider taking up leading. Not every woman might want to lead. But why not assume that every woman can lead? That every woman is potentially a better lead than every other man?

You know, that if women have this, if men have this – this one point of rebellion of self-worth and power – they are putting just one more pebble onto that bridge. They are one step closer to fucking the patriarchy. It will give them the confidence to do things, to be things, to imagine themselves as more, better, bigger, the best.

If that is the case, then, what are you doing to make it possible for women to take up leading?

Assume that, despite your best efforts, you only get 50% of your women leading. Isn’t that a real triumph?

WHAT are you doing to improve things? What is your manifesto? WHY AREN’T YOU ANGRY?

I promised myself I wouldn’t wade in on this stuff, because it makes me far too angry. But I’ve been going through some documents, and I’ve come across a bunch of drafts for blogposts about gender and dance. inorite. Do I have any other blog posts? Yes, I do. But not too many.

Here’s one I wrote in response to a flare-up online about the problem I had with a particular piece someone wrote ages ago about follows, but which used gender specific language.

To be honest, it feels very first year undergraduate arts degree to raise the issue of gender specific language. It’s such a simple, fundamental part of cultural studies, media studies, literary studies any sort of textual analysis, to raise the issue of gender specific language. I mean, we’re talking second wave feminism here – the sort of issue that was important in the 1960s.

Why is language important to feminism? Or to any sort of critical engagement with the way ideology works? This is old school. When we do semiotics with first years, we explain how language choices and use reveal ideology. Or, in other words, the words we choose to use reveal the way we think about the world. I really like Roland Barthes for the way he explores the relationship between language choices, ideology and social power.

So, to use a very relevant example, the mainstream press and conservative political figures in Australia referred to our Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, as ‘Julia’, rather than as ‘Prime Minister’. But now that she has been replaced by a male prime minister, he is being referred to as ‘Prime Minister’. It seems like a very small thing. But it’s quite important. Yes, it is disrespectful – of the woman and of the office (I cannot imagine an American television reporter calling his president ‘Obama’ in a formal, live-to-air interview) – but it also works to reveal the speaker’s perception of women as less important or powerful than men. And it also works to convince the listener that this is the correct way to address a woman prime minister.

“So what?”, you say. It’s just one example, one word. But this is how patriarchy works. How hegemony works. There’s a whole, massive, huge body of work discussing the role of language in society. I don’t have time to go into it here. But take my word for it: this is a well-accepted and understood analysis of language and society. You can begin with some reading about cultural hegemony, but, really, you’ll have to read up on your own.

Let me explain how I use it here (and how it is commonly used by other socialist feminists):

Yes, it’s just one example. But our lives are filled with millions and billions of these everyday examples. My prime minister – leader of my country – is referred to by her first name rather than her title. When I go to the bank, I’m referred to as ‘Miss’, even though my title – written right there on the bank account details – is ‘Dr’. A middle aged man that I don’t know might call me ‘love’ rather than by my name, in a professional setting. A man refers to me as ‘that girl’ instead of by my name, when addressing me in a public setting. There are sixty million billion examples of this, including http://saidtoladyjournos.tumblr.com/. This is just everyday sexism, friends. It’s terribly ordinary.

What is important here, is not the individual instances of language use, but the relationships between these many instances, the patterns they create, and the consistencies in these patterns. If I never hear a man refer to me as ‘Dr’ in a professional setting, it undermines my professional and academic achievements. It implies that I am a) not worthy of that title, b) I don’t actually own that title, and c) that title might not actually mean anything, when it’s attached to a woman. If I am then also seeing and hearing other women, even the most powerful woman in my country, belittled in the same way, the message is reinforced: women are not owed public respect for their achievements; women are not capable of demanding our respect.

So how does this work in relation to swing dance?

Simply, let’s assume that teachers never use female pronouns when they talk about leading. They only say ‘he’ or ‘guys’ or ‘doods’ or ‘men’ or ‘gentlemen’ or ‘boys’ or whatevs. They never ever say ‘she’ or ‘her’ or even ‘they’. If I’m in that class, I feel as though I am slowly erased. I just don’t exist. I’m not there in that class. The teachers can be looking right at me, me with my boobs and my hair and all the other fairly traditional markers that tell you I’m ‘female’. They can be looking right at me and say “Ok, gentlemen, let’s lead our follows into the swingout,” and I am just not there for them. Either they don’t see me, or they have some weird sort of dysphasia where they can’t differentiate between women and men. I mean, it’s kind of interesting to think of myself as some sort of under-cover spy for the Sisterhood, slipping through defences to plant big fat fucking feminist BOMBS. But not that interesting. I’m like most other students in a dance class – I just want my teachers to acknowledge me, to tell me I’m doing ok. To see me.

Once or twice I can handle it. It’s no big deal. But it doesn’t happen just once or twice. It happens 99.9% of the time. And keep in mind it’s not just the teachers who do this. Other students in class say “Are you being the man”? “Are you doing the boy’s role?” It was not until this year, when I moved into the highest level classes at workshop weekends that I experienced a single weekend where no one said this sort of thing to me in class. I have never, ever, in fifteen years of dancing, been at a weekend where no one commented on my gender, and no one referred to leads as male. NEVER.

Let’s just pause here: most of this insistence on traditional gender roles happens in lower level classes. When we’re at our most vulnerable, and we’re least sure of who we are as dancers. I think that many of us sort of assume that women leading or men following is ok or acceptable in ‘advanced dancers’, because OMGHARD. But it seems far more radical for brand new dancers to do anything other than BE NORMAL.

So, sure, your saying ‘guys’ when addressing your leads in class is just one time. One small thing. It’s just that little thing. It’s nowhere near as important or interesting as that particular rhythm variation. But mate: you are not the only person in the world putting that little word into the discourse. Yes, it is just a straw. But it’s one of a million billion straws, each slowly loaded up onto that camel’s back.

It’s nothing, right? It’s tiny. No one’s being mean to me. No one’s saying I can’t lead, or that I don’t deserve to lead. I’ve only ever come across one or two teachers who’ve openly said that they won’t use gender-specific language. But I can count on one hand the number of teachers who’ve openly, explicitly encouraged me as a woman lead. Those moments shine in my memory. I take them out and polish them. They’re so important to me. Once, a female teacher whispered to me in class, “Don’t you ever give up leading.” It was the most important thing anyone has ever said to me about dancing. When I’m just so fucking tired of it, I take out that memory and I hold it in my hand for a minute. I don’t have to be the best. I just have to keep going.

[RAGE EDIT—God fucking damn it. What the actual FUCK. This is fucking crazy. CRAZY. Dancing should be fun – not a battle! WHY can’t we just stop being arseholes, and START being grownups about this? Use gender-neutral language. Don’t be a dickwad.— /]

So I literally do not exist in some classes. The woman lead is not here. We are invisible. What does this do? It tells students that women leads aren’t ‘real’ leads. That we aren’t as important as male leads. In my experience, it’s resulted in people saying to my face that I can’t teach as well as a man, because I am a woman teaching as a lead. Many people have said to me that people won’t want to learn from a female lead, or from two women leading together. So many people have told me that it will be/is difficult.

You know what? It’s not. It’s the least difficult part of my job as a teacher. In fact, I rarely stop to think ‘oh, does my vagina impede my ability to scat?’ I can say, categorically, that being a woman does not make me a rubbish lead teacher. I’ve got plenty of other things that make me a dodgy teacher :D Other people’s ideas about women leads as teachers can make them shitty students, but that’s not my problem.

And I think many of us can say that women leads do exist. We’re out there, every night, across the world, kicking arse and taking names. Leading. We’re good at it, we’re great at it, we’re the best at it, but we’re also shit at it, ordinary at it, just plain capable. We’re just as diverse a group as male leads.

Now, ask yourself: how often do you see men follow? It should frighten you, worry you that male follows are so very rare. This is the real problem: patriarchy screws over men and women. It’s not just a matter for women. It’s not just a women’s issue. It’s an issue for all of us to be concerned about.

But all that is really just an introduction to a piece I wrote earlier. Let’s get into it.

Why is gendered language in a swing dance context important?

When we generalise, and say ‘most follows are women, therefore it’s ok that we always refer to follows as ‘she’ or ‘her’ or female’, we are making some mistakes.

1. What evidence do we have to support the statement that ‘most follows are women’?

Why can’t we just assume that women are as likely to lead as men, and men as likely to follow as women? If we just make this assumption, then maybe we’ll find this becomes a self-fulfilling prophesy.

One of the most important moments in my dancing life was at Herrang, in a class with Peter Loggins and Sugar Sullivan. We had no women leading in the class. Sugar was explaining something, and said something like “And when we do this, men, you have to… oh no. Wait. Girls and guys lead nowadays, and that’s alright. So I’m going to say ‘leaders’.”

My heart LEAPT. Here was a old timer saying, without provocation, that not only was it ok for me to lead, but that that was ‘ok’, and that it was important for her to recognise that. By the end of our next class, half a dozen women were leading. Like GUNS. Say it, and you make it so.

2. When we say ‘most follows are women’, the more disturbing correlative point is that we are also saying – implicitly – that most women are follows.

Or, as it plays out in a discursive sense ‘all women are follows’. This is highly problematic. I have never seen a scene where allthe women dancers only follow. I know virtually no female teachers at an international level who can’t lead.

So by declaring ‘most follows are women’, with the correlative statement ‘all women are follows’, we make the female leads disappear. More importantly (because a lot of women choose not to identify as ‘leads’), we make women leading disappear. We are saying that ‘women do not lead’ (because they are following). The following point would be that ‘women can’t lead’ because #vagina. This is just weird. We can’t make that argument, that the biological nature of ‘being a woman’ makes us unfit to lead. Sure, my (enormous) bosom might make some moves challenging, but it doesn’t actually make it impossible for me to lead. And I’m not quite sure how having a vagina would impede my movement. If anything, surely internal genitalia are an advantage in lindy hop.

….that’s all just crazy talk. Let’s stop there.

So, can we argue that nurture has resulted in women being ‘unfit’ for leading? Hm. Considering how diverse we are, I’m not sure you can make that argument, not across cultures, and not even within a single city. But let’s go crazy. Let’s assume so. Nurture is, by definition, mutable. It can be changed. If this is the case, then perhaps in creating dance classes and scenes where women feel comfortable leading, and men feel comfortable with women leads, we are doing something profoundly radical. We are changing social relations. We are undoing ‘nurture’, or the effects of cultural conditioning.

That’s exciting. It’s a big call, though.

Is it too much to ask of lindy hop? People have spoken about the Savoy ballroom as overcoming segregation, with white folk dancing with black folk. That’s a lot to ask of lindy hop, that it overcome legislated, ingrained racism. But lindy hop did it. Surely we can ask a little more of what is, at heart, a profoundly transgressive dance. I have discussed this before, and in fact, I am exploring this idea every day, with everything I do. In the context of patriarchy, every time I step onto the dance floor as a woman, every time I DJ, every time I manage an event, every time I express my opinion, I am committing an act of radical feminism. I am undoing patriarchy. But mostly it just feels like dancing. Normal.

3. When we spend this much time and effort defining women as follows and follows as women, we make following and women the ‘other’, or the problematic role/gender.

The feminine becomes one we have to spend a lot of time discussing. Why don’t we feel the impetus to define and redefine the masculine this way? It is because we normalise leading as masculine. And there aren’t enough people agitating, and asking ‘why aren’t men following?’ What, then, we should ask ourselves, are the benefits to maintaining patriarchy? Why aren’t people shouting about it? Who benefits from the status quo?

This is important, because leading and following do not occur in a social and cultural vacuum. How do these roles – leading and following – and their gendering correlate with broader social roles? How is leading masculinised and following feminised in our culture?

I could go on and on and on about this. How do boringly heteronormative ideas of the lead/follow male/female relationship permeate and inform our conception of lindy hop?

Let me throw this at you:

– passive/receptive/responsive/object (the ‘heavy follow’, the ‘light follow’ – objects to be moved)

– decision-making/active/reactive/subject (the ‘strong’ lead, the one who ‘moves’ the follow – subjects moving objects)

If you’re a dancer with even an intermediate knowledge of dance, you know it’s simply not that simple. This is a very amateurish, beginnerish understanding of leading and following. We understand that follows are actively engaged in the partnership, and that any decent lead is as responsive as a follow, reacting and responding to what they feel happening in the partnership and to the floor around them. I’ve done some very close textual analysis of this before in the post ‘Lindy hop followers bring themselves to the dance, so I won’t go into it again.

So there are two jobs to be done here.

1) Undo that boring gendered dichotomy idea of leading and following, by redefining following as active, and leading as responsive.

Most advanced dancers are all over these ideas. In fact, one the most interesting and challenging ideas getting about in higher level classes, conversations and choreography in the lindy hop world today, is how a lead might actually make their leading work to accomodate and encourage active follows in complex ways. It’s as though most people have just gone ‘of course! durh!’ to the suggestion that active follows are a great idea. They’ve just moved straight on to the next challenge: leaders are asking themselves ‘how do I encourage and facilitate active following?’

It’s so exciting. It’s like they’re saying ‘Feminism will make me a better lead. Now how can I play a role in feminism: what can I do?!’ And they’re getting off their arses and figuring it out themselves.

2) redefine the language we use to describe these roles.

Why is this important? Isn’t the important part just to redefine our thinking about these roles? This is where my background as a discourse analysis scholar comes into play. I believe that language is important.

Any dance teacher worth their salt knows that what they say in class has a profound effect on their students’ learning. Talk too much and the students lose interest. Talk about arms, and the students focus on arms. Scat and the rhythm becomes clear. Use only numbers and the students’ understanding of rhythm is limited.

Language matters to dancers.

It’s really not difficult at all to shift from using gendered pronouns when talking about leading and following. Or is it? In my own class, my teaching partner and I found it harder than we expected. There was a period of a few months where we struggled. This suggests that the way we think about gender and dance roles is related to language, and that these association are quite firmly rooted in our understanding of dance.

But once we did it, we found that using this language really isn’t difficult. It becomes normal.

I mean, fuck. We transcribe complex jazz steps from blurry old black and white films, break them down, learn how to do them, then teach them to students. Learning to say ‘lead’ instead of ‘him’ is a fucking cake walk in comparison.

I wrote this post in April this year. And I began it with Clementine Ford’s piece ‘Why ‘can you have it all’ is this century’s dumbest question’.

I’d like to make a provocation:

A dance floor of one’s own is as important as a room of one’s own. And just as Virginia Woolf’s essay(s) are problematic for women of colour, the idea of a dance floor of one’s own is not without its own problems. But let me begin to explore the idea, and we’ll pick up those problems as we go.

There something powerful about simply having the time and energy to commit to self expression, to a creative art, to pleasure for pleasure’s sake.

Accepting and acting on the idea that what you have to contribute is valuable, important, creative, funny worth while is a radical act. Speaking up – getting on the dance floor – is a radical act, because it presupposes your ideas are important. In this respect, dancing is a contribution to public discourse, to public life, and to creative, social life. This is where lindy hop – as a social dance that you do with other people in public spaces – is different to writing or painting or other visual arts. It is a public, social cultural and creative practice.

The distinction between professional dance and amateur dance is important. There is the sense that being a dancer is ok if you can ‘make a living from it’ or ‘make something of it’. Dancing just for the sake of dancing – for the pleasure of your own body in movement – is dismissed as irrelevant, trivial, selfish, unimportant.

There is nothing more important than a woman accepting, and being able to accept, that her own pleasure, her own interests, her own ideas are important and relevant. Important and relevant to her. They do not need to be deemed important by a male observer, or by culture and society as a whole. They can be wonderfully, deliciously, selfishly important to the person dancing, and to her alone. She needn’t even be very good at it, so long as it makes her feel good and brings her pleasure. Or even if it brings her occupation, challenge, stimulation. This is important in the broader context of patriarchy, where women are expected to subsume their interests, desires and pleasures in the needs of others. For men, for children, for parents, for employers, for babies. One of the most challenging and powerful parts of lindy hop is that it can exist solely for a pure, social and selfish pleasure.

Clementine Ford makes this point:

It’s abundantly clear that women … aren’t considered to have ascended to the status of accomplished human being until they shuck off that amateur mantle of ‘woman’ and become mothers.

In this sense, women are expected to prioritise the needs and interests of others. To concentrate solely on art or creative practice, to use her body for something other than making babies, is considered less important, less valuable. By extension, women are judged for their bodies, not their creative or cultural or social actions. This body must be beautiful, and it must make babies, and these babies must be the centre of a woman’s life.

There is the obvious discussion about women’s bodies and sex to be had, but that is not what I want to talk about. I think the idea that a woman might use her body for something that is not sex or sexual reproduction is quite radical and powerful. I’m not the first to point out the empowering qualities of physical exercise. I’d argue that lindy hop combines the power of adrenaline and knowing your body can be trusted, is powerful, is a source of pleasure and excitement, with the creative and artistic process of painting or drawing or writing. But while painting or drawing or writing in their most traditional forms are quiet, solitary things, lindy hop is loud and exuberant and dangerous. Even when it is at its quietest and gentlest.

As a jazz dance, lindy hop responds to jazz music, which combines both structure and improvisation. Rules and rule-breaking. Cooperative and collaborative work with individual, independent creativity. While we might shut ourselves away to write a book, lindy hop demands its participants publicly accept and value a woman’s creative work in a public, and creative communal space. Lindy hop is a public discourse, a public creative space. And women’s contributions are not only tolerated, but expected and required.

On a more prosaic level, simply choosing to leave the house to go dancing is a radical act. I choose to walk away from the dirty dishes, the unfolded laundry, the unwritten essay, the incomplete report, the unfinished argument. I go out into the night, by myself, to meet other people in a public space. And in that public space, I can commit myself, wholly to my own body, to my own pleasure and satisfaction. When I dance with men, we are both negotiating a public relationship that is necessarily mutually respectful and creative. Though there are always moments when the power dynamic between partners is fucked up (the disrespectful, controlling lead), lindy hop itself – with the open position – builds in time for subversion, resistance and powerful self-expression. Improvisation is expected. It is required.

This is where solo dance and women leading become the ideological icing on the cake. A woman leading is an act of radical politics in a community that cannot even manage to divorce the word ‘lead’ from male pronouns.

The follow up piece to this post, then, is what happens when a woman lindy hopper has a baby? This is particularly relevant to us now, as the most recent generation of lindy hopping women move on to having children. Is there space in lindy hop for women with babies? Can they have it all? At this point, I want to rage the way Clementine Ford does. This is not the question that I want to ask.

We should be asking: “How can we make room for fathers with children in lindy hop?” and “How can we make room for children and babies in lindy hop?” We should not be assuming that caring for babies is the sole province of women. It is the work of men and women, in partnership, alone, and with same-sex partners. More importantly, for a community which has perennial problems with longevity and social sustainability, children are the responsibility of all of us, of all lindy hoppers. It is in our interests (as well as theirs!) to build dance communities which accommodate children, babies, parents and carers. Not simply for the sake of those children, or for our communities.

Our creative worlds are made eminently richer by the presence of the dancing woman, who has that moment in time and space to be utterly submerged in her own body and own dancing pleasure. Because that moment of utterly independent pleasure is essential to the health of our communities as a whole. We cannot be a socially sustainable community if we assume that for the majority of our dancers (and women are the majority of our dancers in lindy hop) their own dancing can never be their highest priority. Adequate child care facilities, supportive partners, robust communities allow women moments where they can make their own dancing the most important thing in that moment. Child care does not disappear for them in that moment, but they have the freedom to accept and believe and be confident that someone else is looking after their child, and that they can be trusted.

Our culture spends a lot of time – all of its time? – convincing us that men in particular cannot be trusted. That they are dangerous. And that women have to protect themselves (and children) from men. From the world. Working to secure child-friendly dance communities works hand in hand with securing women-friendly dance spaces, without sexual harassment and bullying. And, ultimately reworking our perceptions of bodies and bodily responsibility are good for men too. If it is bad to be continually thinking of yourself and your body in danger, what must it be like to be continually, always regarding your own body and self with suspicion? To fear, all the time, that you might hurt someone. You might rape or assault them. That your body cannot be trusted, that you cannot be trusted? Patriarchy is not kind to men either.

Having said, that I think Ford makes an excellent point when she says

Gender inequality wasn’t created by women and their unreasonable ambitions. It’s vital that we shift the focus of women’s oppression back to its beneficiaries rather than perpetuate the kinds of meaningless conversations that imagine these things are perplexing problems for women alone to solve.

I think we need to start engaging with masculinity and ideas about men in the modern lindy hopping world. \

No, actually. That’s incorrect.

So far’s I can tell, this is how it goes:

Sister writes moderately feminist (not especially radical feminist) piece about gender shit in dancing.

Some of her peeps read it, link it up. Word circulates. Peeps get to chatting. Tumblr gets a-whirring. Discourse, discussion, grown up talk and thinking happens. All is cool.

A high profile blogger/aggregator finally gets to that feminist piece in their rss. They link it up on their well-trafficked fb page with some sort of provocative line about feminists or boobs or gender wars or who-fucking-knows-what-just-make-it-shit-stirry.

The sister’s piece gets nine million billion hits, and a squillion really nasty emails/comments from dickwads who didn’t bother to read the post, but came in swinging because they were primed that way by the high profile blogger/aggregator. Shitstorm ensues. High profile blogger/aggregator’s stats go through the roof.

Sister feels a bit low. Blames herself for speaking louder than a whisper in public.

Peeps with brains send that sister emails or messages on fb or whatevs voicing their support. Remind her that her word is legit and important and valuable.

High profile blogger/aggregator carries on, business as usual. Unless someone calls them on their bullshit. Then they sook.

For fuck’s sake, people. You know there are too many fuckwit blokes out there in the online dancing world, just itching to get up there and blow some uppity female away for, oh, I don’t know, being out in the internet on her own at night wearing something inappropriate (like an independent thought). Think about how you prime your readers before you send them off to linkbomb, k? Maybe even have a think about writing your own piece calling fuckwits on their bullshit behaviour?

In May 2011 I wrote a post called A difficult conversation about sexual violence in swing dance communities

I need to bump this post again, because it’s been getting a stack of traffic lately.

This was one of the most difficult things I’ve ever written. When I started linking ideas together, and mapping out the way gender roles and ideology contribute to sexual violence in my community, it nearly broke my heart. I was so, so upset by the connections I was making. I didn’t want to realise these things about my people, my places. I started being afraid. Afraid of my own dance spaces – the places I felt best about myself. So I decided that rather than letting this sorrow eat me up from the inside, I’d do something about it. Fear and anger and despair will eat you up and finish you. So you need to step up, do something, make something, change something. Be a force of good. Remind yourself that jazz dance is built on a history of resistance to oppression. It is radical politics. It is a powerful tool. A powerful idea.

I am not going to accept the general response to these issues: that violence towards women happens on the street (not my street!), in bars (not my local!), to ‘slutty’ women (not my women!), and is perpetrated by rough/violent/aggressive/’low’/male strangers (not my friends! not me!)

Sexual harassment happens in your lindy hop community. In your city. To your friends. And it is perpetrated by people you know, maybe even by your friends. This makes it your responsibility.

The only logical response to this is sadness, despair, RAGE. And then action. Do something. Do something!

(from sinfest, via mindlessmunkey)