Ok, so when I heard Falty was teaching at MSF, my first thought was not ‘oh, wonderful – nice classes’ or even ‘hellz yes; yr gender norms, we will fuck them up‘ but ‘oo! can haz DJ?!’ I’m organising the DJs this year for the event, so I just dropped an email off to the man, and – ta da! – we had DJ.

Mike very kindly did a set at the late night last night, and it was (and here, you must understand, I am understating the case) frickin neat. He did a really fucking great set. The sort of stuff that I’m really loving at the moment; lots of energy, grunt, dirty rhythms, etc etc etc.

I was doing the set before him, to warm the room, and I did an ok set – nothing too exciting, mostly things people’d heard before, etc. I was really trying to just get things cooking a little, and not to kill people after their night with the tempo-ly challenging Red Hot Rhythmakers and before Falty introduced them to the Kicking Of Arse.

After he was done with that (and after he exposed his person to a room full of appreciative dancers of all genders), I kind of chilled things off a little with a lo-fi, medium-slow tempo set of stuff I adore, but which I rarely play for dancers. By this point people were a) pissed as newts, b) absolutely knackered, c) drained like sinks, d) mixed like dodgy metaphors. So I kind of mellowed it. This weekend I’d been asked to go easy on blues with DJs, and really to offer a program packed with lindy hop. So I didn’t want to go solid blues, but I did want to ease off the tempos.

side note:

It’s been really fun, actually, to work with the DJs this year. They’re all really capable and together, AND they’re all really good DJs. I’ve been super happy with their work so far. I hope I don’t jinx things, but they’ve done just the right stuff all weekend. The band breaks have been DJed masterfully (Loz warmed the room perfectly on Thursday, Keiran did a lovely ‘sophisticated swing’ introduction to the 20s society band style of the Rhythmakers in the fancy Fitzroy Town Hall (which he then shifted over into more raggedy lindy hopping action). Lexi did a fucking scorching set at the late night on Friday, which made me dance and dance and dance til I thought I might pass out (I’m spinning around!). I didn’t hear all Sharon’s set, but she was moving nicely from Lexi badassery to more mixed lindy hopping goodness when I left. Last night Falty was superfine, and I was actually pretty happy with the set I did after him. I started at 3 (with workshops the next day), so the room did empty out a bit, but the numbers stayed, and I was glad I didn’t go down into blues or keep trying to push the tempos. I really wanted to play seriously scratchy, lo-fi stuff with silly lyrics, dirty lyrics and familiar lyrics done a little wackier.

Tonight the band is the Sweet Lowdowns, who I do love. They’re a smaller subset of Rhythmaker folk, but they do hot combo style rather than a bigger, more society type 20s sound. The brief for the late night (which is at the same venue as the band) is for ‘blues/lindy combo’, which is going to be a bit challenging. I have Keith doing the first set, so I’m hoping he’ll do a straight lindy transition from the band. Then Manon is booked to do a lindy-blues mix. Her style is a little different – she’s really the only hi-fi/heading-towards-groove DJ on the program, and to be honest, even I’m ready for something a little slicker and saucier. I’m closing the night after her, and I’ll probably do the same sort of stuff… or whatever the crowd are digging. It’s going to be lots of fun.

That’s my last set for the weekend. I’ve been doing all the little fill in jobs over the weekend, the ones that I don’t like giving other DJs because they’re little and a bit shitty. So I’ve done the social breaks during the comp (that was boring. Watching comps is boring, I’m afraid), I did 4 songs for the charleston comp on Friday, I did a real set last night to warm for Falty, and I did a small closer set after him. And I suspect tonight’s set will be a littlie as well. I did have some reservations about putting myself on all those sets, but the only one that actually really felt like a good, solid DJing gig was the one before Falty. I have also tried hard to put the other DJs on good, solid gigs as well as any band breaks. But there’s not a lot of solid DJing this weekend, because of the bands, so it’s been hard. There’ve been hour long blocks before the bands, then 30 or 15 minute breaks during the bands, so those band break DJs are getting some solid action, I hope. The bands are, though, really really GREAT.

These are issues I struggle with when I coordinate DJs. I pick DJs I think are great. And then I want to show them off. But it’s hard to flaunt a badass DJ when they’re supporting a band – the band is the main attraction after all. I’m beginning to feel that it’d be easier to just put a CD on in band breaks. I mean, it’s not like the olden days in lindy hop, when the bands were so bad you really _needed_ a good band break DJ. But then there are lots of annoying jobs during band gigs that require a real DJ – playing music for performances, welcome dances, etc – so you actually need a DJ who’s really responsible and together…

It’s a hard set of decisions, really. I think it’s a better idea to keep the number of DJs at a gig low, and then to use them in a few settings. So long as they’re cool with that. But then you get other problems: DJs who aren’t involved feel left out; the DJs who’re working a lot get a bit tired; if you’ve blundered and misjudged the type of DJs you’v chosen, the crowd are stuck with them all weekend. The last one isn’t really a big problem, I don’t think. I put a lot of effort into finding out exactly what the organisers want from the music – old school? A mixed platter? What’s their creative ‘goal’ for the event? Do they want ‘all really experienced DJs’? A mix of old and new so as to do some community development with encouraging new DJs? All local? A mix of interstate/overseas and local?

These can sound like wanky questions, but it really helps to talk to the organiser and find out what they want the final event to be like. Then I make suggestions and try to put together a list of people I think will work for the event. And then I get the organiser to check that list and give me the nod. It can get tricky if the organiser isn’t a DJ or doesn’t really get into music in a big way. In those cases I try to be a bit more active in my thinking, and to ask questions about their ideas for the event in a more general way. Then I try to come up with DJs who’ll help make the event work that way.

The next step is, of course, to invite the DJs you want. It can be hard to persuade DJs from out of town to come to an event where they’ll only get free entry, and then be paid $20 or $30 per hour, and without any meal or flight payments. I’m also thinking that it might be a worthwhile investment paying DJs more and giving them better packages, just so we can guarantee their presence and work. They certainly do that in America at the bigger events.

This issue is really indicative of a transitional moment in Australian swing dance culture – we just don’t seem to value DJs that highly. Which of course suggests that social dancing isn’t that important. I think this is changing, though. But we are beginning (as a scene – there are individual exceptions of course) to see broader cultural shifts in how we value DJs and music. But the sheer fact of geography has meant that dancers are unlikely to travel _just_ for a social dancing event, unless it’s guaranteed badass, has a good reputation or offers something else along the way (eg the Hellzapoppin’ comp).

These are all issues I have to think my way through. I’m still not entirely sure how I’d plan my ‘ideal’ event. Would I get in just a handful (as in 4 or 5 maximum) DJs, pay them really well, and give them great deals, then use them quite thoroughly on the program, promoting them heavily as a key feature of the event? What would this do to the status of the bands, though? Bands are, really, the best fun and the best part of a weekend. If they’re good bands. Do I really think it’s a good idea to create a sort of hierarchy of knowledge and status with DJs somewhere higher up? I mean, isn’t this a bit self-serving, speaking as a DJ? Why should DJs be more important than the people who clean up after the dance?

Part of me argues that DJing requires a significant investment of time and money, and the development of skills and professional contacts and networks, so really it is more value-laden than cleaning up after the dance. But then there are clear gender divides happening here. DJs are usually men, and the cleaner-uppers and volunteers generally, are usually women. It’s actually been nice to see in the last few years, that this gendering is shifting. Women are over represented in volunteer labour (as they are in the broader community), but they are steadily creeping into the DJing ranks. MSF features five women DJs and three men. This has to be a first in Australian DJ terms. I’ve never been at an event with more women than men DJs. And I have to say, they’ve been absolute GEMS.

I’ve _never_ had such a professional, capable team of DJs. No one’s been late to a set, no one’s lost anything essential, no one’s missed a set (!!), no one’s failed to bring the right gear. Everyone’s been really keen to pull out their best work, everyone’s been really conscientious, everyone’s done really top quality sets, everyone’s been an absolute pleasure to work with. It’s been a really wonderful experience working with this group. This isn’t to say that I haven’t also had good experiences with other DJs at other events, but this one just seems to be working really well. AND I’ve had some really good dances.

My one concern, though, is that the heavy emphasis on music from the 20s, 30s and 40s has alienated some of the punters, especially the ones who’re new to the dance, or aren’t actually into old school music. This type of music is quite chic with the Melbourne teachers at the moment, but it hasn’t always been. Some of this stuff can be a bit challenging if you’re not used to the low audio quality, the musical structures, or if your dancing is really limited to just a few basic steps. The more dancing skills you have, the more experience with historic dance forms you have, the more accessible you find this stuff. It’s helped that the teachers for the weekend are into this action, so they’re teaching with this type of music. But part of me is thinking ‘isn’t it time we went hi-fi here?’ All of the DJs (pretty much) have dropped contemporary recordings into their sets, but the music these modern bands are playing is still pretty old school.

On the other hand, I think that Australia is approaching the point (finally) where we can actually specialise musically at each event. I think it’s a shame not to produce events with particular musical or stylistic focuses. I like to see events that have a consistency in the branding (logos, PR material, individual event PR), bands, DJs, competition structures, performances and classes. So Soul Glo is successful in part because it presents a soul-focussed event for swing dancers, with a strong blues sub-focus. Hullabaloo in Perth has always had an old-school focus, but that event is more of a complete package, and they offer such a quality event the music is really only one component of a very solid program. I think MLX could actually do with stronger branding on this front. It’s been ‘solid swinging jazz’ since 2005 when it went all-social, but I think this branding needs updating and strengthening. I can see why some events wouldn’t want to take the risk of alienating potential punters with such specific branding, but then, I wonder if it’s not worth taking a risk? As a dancer, I’m certainly looking for a particular experience when I go to an event. And a ‘good weekend of dancing’ isn’t really enough any more – I want something a little different. But still within the vernacular jazz discourse, though… unless I am at Soul Glo, and I know what I’m getting.

Ok, so that’s enough of that.

Here’s the set I did after Falty last night.

title band album bpm year length

It’s Your Last Chance To Dance Preservation Hall The Hurricane Sessions 179 2007 4:31

Georgia Grind Louis Armstrong and the All Stars (Trummy Young, Edmund Hall, Billy Kyle, George Barnes, Squire Gersh, Barrett Deems, Bob Haggart, Velma Middleton, Yank Lawson) The Complete Decca Studio Recordings of Louis Armstrong and the All Stars (disc 05) 124 1957 3:23

Deep Trouble Les Red Hot Reedwarmers King Joe 179 2006 2:55

Blue Leaf Clover Firecracker Jazz Band The Firecracker Jazz Band 111 2005 4:59

Do Your Duty Bessie Smith acc by Buck and his Band (Frank Newton, Jack Teagarden, Benny Goodman, Chu Berry, Buck Washington, Bobby Johnson, Billy Taylor) Classic Chu Berry Columbia And Victor Sessions (Disc 1) 121 1933 3:31

Wipe It Off Lonnie Johnson and Clarence Williams acc. by James P. Johnson, Lonnie Johnson, Spencer Williams Raunchy Business: Hot Nuts and Lollypops 122 1930 3:20

I Like Pie I Like Cake (but I like you best of all) The Goofus Five (Bill Moore, Adrian Rollini, Irving Brodsky, Tommy Felline, Stan King) Goofus Five 1924-1925 188 1924 3:15

Don’t You Leave Me Here Jelly Roll Morton’s New Orleans Jazzmen (Zutty Singleton) Jelly Roll Morton 1930-1939 143 1939 2:23

It’s Tight Like That Jimmie Noone’s Apex Club Orchestra The Jimmie Noone Collection 144 1928 2:49

Downright Disgusted Blues Wingy Manone and his Orchestra (Chu Berry) Classic Chu Berry Columbia And Victor Sessions (Disc 5) 129 1939 2:31

How Do They Do It That Way? Henry ‘Red’ Allen and his Orchestra (JC Higgenbotham, Albert Nicholas, Charlie Holmes, Luis Russell, Will Johnson, Pops Foster, Paul Barabarin), Victoria Spivey and the Four Wanderers Henry Red Allen And His New York Orchestra (disc 2) 139 1929 3:20

On Revival Day (A Rhythmic Spiritual) (06-09-30) Bessie Smith acc by James P. Johnson, Bessemer Singers Jazz Cats – Jazz to Wake Up to 163 1930 2:58

That Too, Do Bennie Moten’s Kansas City Orchestra (Count Basie, Jimmy Rushing) Moten Swing 123 1930 3:20

That’s What I Like About You Jack Teagarden and his Orchestra (Charlie Teagarden, Stirling Bose, Pee Wee Russell, Joe Catalyne, Max Farley, Adrian Rollini, Fats Waller, Nappy Lamare, Artie Bernstein, Stan King) The Complete Okeh and Brunswick Bix Beiderbecke, Frank Trumbauer and Jack Teagarden Sessions (1924-1936) (disc 6) 166 1931 3:27

The Blues A Artie Shaw and his New Music Self Portrait (Disc 1) 123 1937 2:52

The Right Key But the Wrong Keyhole Clarence Williams and his Orchestra Clarence Williams and His Orchestra Vol. 1, 1933-1934 103 1933 2:36

Falty had played a set with quite a few contemporary New Orleans bands (Jazz Vipers, Preservation Hall, etc), and a lot of bands quite like the ones I usually play. In fact, we had a few of the same songs on our short lists when we compared our sets just before we swapped over. This was really exciting – I got a chance to dance to stuff I adore, but don’t DJ very often. Then Mike’s status allowed him to take risks I couldn’t, and his actual DJing _skillz_ made it work for him. From here, I could take more risks with the music I played. That’s why I went old school. I didn’t try to make people crazy and upenergy the way I usually do, as people were shagged, and Mike had really done that action quite thoroughly already.

I played the first Pres Hall song as a way of moving from Falty to something else. I was feeling a little emotionally battered myself, so I thought I might ease it off afterwards. I think that song was a bit in your face for a first song, though. I had kind of tossed up between that and their version of ‘Sugar Blues’, so as to completely change things up, but I chickened out on such a bold move. I also didn’t want to signal ‘this is where the blues begins!’ so clearly and risk losing half my (dwindling) crowd.

I played ‘Georgia Grind’ because I love it. Falty had played a way up-tempo, scratchy version earlier, and I thought it’d be cute to signal my change in vibe by playing a hi-fi version by Armstrong. It’s a little twee in parts, but the band is so good it really overcomes that later on in some of the choruses.

I <3 Les Red Hot Reedwarmers. Make sure you search for them on youtube – they’re a great little French band who do wonderful, wonderful Jimmie Noone stuff. This song is kind of cute and mellow, but also musically amazing, and recorded live. Props to them.

‘Blue Leaf Clover’ always goes down well, if I prepare the set for it properly first. It’s by the Firecracker Jazz Band, which was kind of a reference to my charleston songs the night before. This is such a great band.

Really, I was headed towards Bessie Smith all the time. I find that whenever I play her, people love her. They really respond to her versions of songs they know, but also to her more obscure stuff. This song is super neat, and you can’t really go past the line up in the band. This was a transition (with its brass solos) from the Firecrackers to the next song with its piano/guitar combo. It’s a little lighter hearted than Bessie, but it’s much dirtier. And it’s really fun. These are two of my most favourite songs of all time. I especially like the man-singing-like-a-woman vibe, which I revisit later with the Teagarden/Waller duet.

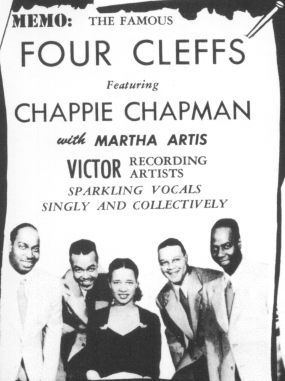

I had to play this superior Pie/Cake version which Trev put me onto ages ago. Go Goofus Five! I think this song is a good example of how exchanges are super inspiring for DJs – they give us a chance to hear other DJs bring their wickedforce and then rip it off for our own gain. Ha ha! I like this version because I find the Four Clefs version a bit twee and overplayed, but I love the melody. I hoped it would twig the ‘favourite’ nerve in the dancers, but then twist it with a more uptempo vibe.

Jelly Roll, because, well. Jelly Roll. This is a nice, chunking, _pushing_ song, that doesn’t drag – you feel like you’re going somewhere with it. It’s an easy tempo, but it has a bit more energy. We needed that energy if I was going to sit down here on these lower tempos. I actually think the vocals are just right – a nice, rollicking, swinging rhythm that contrasts really nicely with the slightly more straight-ahead rhythm section.

Jimmie Noone! I do love this man. And I love this song. More suggestive lyrics. But the expression ‘tight like that’ is kind of cool because it sounds like a really cool way of describing how something is just plain good stuff – “man, it’s tight like that.”

Wingy Manone, for a little more swing, and back in that 1939 later swing rhythm. Mike had played a few Manone songs, and I wanted to reference them a bit here.

I had wanted to play some Spivey/Henry Red Allen win, but all I could find was the slower stuff, and I wanted to avoid the bluesy vibe. But then I was reminded of this, which is one of my super favourites. I’d just been crapping on to Mike about how I liked the Spivey/Allen combination, and how it reminded me of the Rosetta Howard/Allen combination, and how Howard was the one who led me to the Hamfats in the first place (we’d just been talking Hamfats).

Bessie Smith. Because. People liked this, but it was a little uptempo, and a little too jesusy for serious dancing. But it’s fun, and people like it.

Bennie Moten, while I’m there. Because Basie always wins. And the Jimmy Rushing addition (with the ‘Good Morning Blues’ lyrics) is full of awesome. Gotta love a bit of a accordian solo in there.

The Teagarden/Waller duet ‘That’s What I Like About You’ was perhaps a bit mistimed – too fast, too straight for this time of night. Having said that, it’s also wonderfully queer-as-fuck to hear Teagarden (sigh) singing a love song with Fats Waller (double sigh). They would have known exactly what they were doing. This is queer in so many wonderful ways. These guys were pretty transgressive (a black guy and a white recording together in 1931, who also played together live in Chicago*; all the drug references; the gender-play in this song itself), and this love song with the humourous twist _almost_ undoes the queer… and then it doesn’t. It’s still Jack Teagarden, who has the sexiest, swingingest voice EVER, singing a love song to Fats Waller, kind of comedic timing and also king of poignant understatement. They’re singing a song about mismatched, chalk-and-cheese love. It’s perfect.

I closed with Artie Shaw because that song is nice and swinging, it’s easy to dance to and it’s really nice. It’s also pretty slow and mellow, but also kind of chunks along and doesn’t drag.

I really enjoyed this set. Though the room slowly emptied out til I called it at 4am, people were still dancing.

Hoo-rah for lindy hop.

* The Fats Waller/Teagarden connection is quite cool. They also did a song called ‘Lookin’ Good But Feelin’ Bad’ (Fats Waller and his Buddies (Henry ‘Red’ Allen, Jack Teagarden, Albert Nicholas, Otto Hardwicke, Larry Binyon, Eddie Condon, Al Morgan, Gene Krupa), 1929) which Les Red Hot Reedwarmers do superhot. That band is pretty much 100% rockhard awesome. The ‘That’s what I like about you’ band isn’t quite as good, but it is sporting Adrian Rollini, who I have a bit of a thing for. At any rate, it’s all Chicago, and it’s all quite subversive stuff.

Teagarden is also interesting for his work with Louis Armstrong – more race stuff that kind of fucked the mainstream American conservativism about. In the early days at least.

I wrote about Armstrong, race etc in these posts:

What again?

magazines, jazz, masculinity, mess

pop culture, jazz and ethnicity

Category Archives: cat blogging

magazine themed jazz prn

Magazine-themed prn from the ‘Jam Session’ pics in the Google/Life set Gjon Mili did for Esquire:

(NB that little group in the bottom left hand corner are from Vogue magazine.)

Mili of course made Jumpin’ the Blues, and also this freekin great clip of rockstars:

lists and canons in jazz

An interesting discussion has cropped up on SwingDJs called “30 Good Hot Records” from LIFE. This is what I’m about to post in response.

I love lists of iconic or ‘good’ songs/books/films/texts. I love them because though they are presented as definitive, they are always[ more effective as a provocation than a definitive answer to questions about what counts and is important enough to be listed. Discograhies work, pretty much, as definitive ‘lists’ or ‘canons‘.

I’ve come across a few different uses of ‘hot’ in articles and books from the 1930s, particularly in reference to discographies. Kenney’s discussion of jazz in Chicago outlines the differences between ‘jazz’ or ‘hot’ bands and music and ‘dance’ bands. These differences are not only musical, but also inflected by race, class, the recording industry, live venue management and ownership, gender… and so on. I’ve also come across quite a few discussions in an academic (rather than populist or ‘music critic’) sources about the expression ‘hot jazz’. The most useful sources point out that any attempt to finally define ‘hot’ or ‘jazz’ is not only difficult, but also problematic.

Krin Gabbard discusses the cultural effects of constructing canons – in which discographies play a key role – and points out that lists of ‘hot’ or ‘important’ or ‘real’ jazz records aren’t neutral or objective lists of songs – they are highly subjective and negotiated by the author’s own ideas about music and place in society generally.

Kenney (who’s written some absolutely fascinating stuff about jazz music in Chicago in the 20s) discusses Brian Rust’s discographies, making the point that Rust distinguishes between ‘hot’ and other types of jazz recordings. Friedwald talks a bit about Rust (and other discographers) in his jazz.com articles. Kenney’s research into the recording and live music industry in Chicago suggests that who got to record or play what types of music was actually dictated in large part by record companies’ ideas about race and class and markets rather than musicians’ personal inclination. That last point suggests that you could make some interesting observations about the correlation between race, class, recorded songs, ‘popularity’ and ‘jazz’ in Chicago jazz during this period. I don’t know enough about it, though, so all I’ll say is that you could, but you’d better have some badass sources to support your arguments. And you’d also better be prepared to accept the idea that though America had a national music industry, different state legislations and music cultures resulted in quite different local practices: it’d be tricky to generalise Chicago’s story across other cities and states. Not to mention countries.

Life and other magazines’ comments on and participation in music promotion in the 30s is also pretty interesting – these guys had ideological barrows to push, just as did Rust and other discographers. One of the effects of publishing this type of list (which was no doubt as hotly contested then as it is now – except by a wider audience :D) is that it does stimulate discussion and debate. And, hopefully, record and ticket sales. One thing I’d be interested in knowing is who owned LifeGreat Day In Jazz photo, I think about the fact that it was a photo for Esquire magazine, and that Esquire also produced a series of live concerts, recordings… and of course, photo spreads in magazines. While GDIJ works a fabulous representation of jazz it also serves as a canon, and as such is also subjective, ideologically framed and interpreted (eg asking why are there so few women in this photo leads us to questions about gender and jazz?) Canons are fascinating things, and can be the jumping off place for all sorts of great discussions and debates. I think this is why I was so excited by Reynaud’s session on Yehoodi Radio where he used the GDIJ photo as an organising structure for the music he chose. In that case, the photo became a listening guide for a radio program. I’d just rather not use them as definitive, fixed lists; I like them more as provocations, or a place from which to begin discussing (and arguing about) a topic.

If I saw a list like the one in Life today, I’d be extra-suspicious. Songs on So You Think You Can Dance, for example, are owned by the company which produces that tv show. There’s been quite a lot written about the Ken Burns’ Jazz series and its role in cross-promoting sales of records from catalogues owned by the same media corporation. The Ken Burns example is an especially interesting one: that series does not present an ‘objective’ list of important artists and songs. It is a jumping off place for a very successful marketing project surrounding back catalogues and contemporary musicians like Marsalis. George Lipsitz has written quite a bit about histories of jazz (including Burns’), and he makes this point:

…the film is a spectator’s story aimed at generating a canon to be consumed. Viewers are not encouraged to make jazz music, to support contemporary jazz artists, or even to advocate jazz education. But they are urged to buy the nine-part home video version of Jazz produced and distributed by Time Warner AOL, the nearly twenty albums of recorded music on Columbia/Sony promoting the show’s artists and ‘greatest hits,’ and the book published by Knopf as a companion to the broadcast of the television program underwritten by General Motors. Thus a film purporting to honor modernist innovation actually promotes nostalgic satisfaction. The film celebrates the centrality of African Americans to the national experience but voices no demands for either rights or recognition on behalf of contemporary African American people. The film venerates the struggles of alienated artists to rise above the formulaic patterns of commercial culture, but comes into existence and enjoys wide exposure only because it works so well to augment the commercial reach and scope of a fully integrated marketing campaign linking ‘educational’ public television to media conglomerates. (17)

Lipsitz is interesting because he says thinks like Why not think about jazz as a history of dance? Why not look into the lives of musicians who gave up fame and fortune in massively famous bands to work in their local communities?

Friedwald, Will. “On Discography” www.jazz.com, May 27, 2009 http://www.jazz.com/jazz-blog/2009/5/27/on-discography

Gabbard, Krin. “The Jazz Canon and its consequences” Jazz Among the Discourses. Duke U Press, Durham and London 1995. 1-28.

Kenney, William Howland. “Historical Context and the Definition of Jazz: Putting More of the History in ‘Jazz History'”. Jazz Among the Discourses. Duke U Press, Durham and London 1995. 100-116

Lipsitz, George. “Songs of the Unsung: The Darby Hicks History of Jazz,” Uptown Conversation: the new Jazz studies, ed. Robert O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, Farah Jasmin Griffin. Columbia U Press, NY: 2004: 9-26.

References for my posts on Esquire.

the 4 clefs

The 4 clefs version of the song I Like Pie, I Like Cake is very popular here in Sydney at the moment, played by at least two DJs. I did a little google and found this site discussing them. It’s worth a peak, as they have pics like the one above and a few songs you can listen to.

Personally, I prefer the peppier version of I like Pie, I Like Cake (But I like you Best of All) by the Goofus Five, which Trev pointed me to in late 2008, but which I still haven’t played…

ellington

blues for greasy

modernism + jass = orsm punnage

A new 8track:

Or check the linky.

Songs include:

Putting On The Ritz The Cangelosi Cards Clinton Street Recordings, I 3:38

All I Know The Countdown Quartet 2002 Sadlack’s Stomp 2:57

Digadoo Firecracker Jazz Band 2005 The Firecracker Jazz Band 5:20

My Daddy Rocks Me Les Red Hot Reedwarmers 2006 King Joe 6:17

Who Walks in When I Walk Out Midnight Serenaders 2009 Sweet Nothin’s 3:21

Zonky New Orleans Jazz Vipers 2006 Hope You’re Comin’ Back 5:06

Eh la bas Preservation Hall Jazz Band 2004 Shake That Thing 3:52

Sud Buster’s Dream Rhythm Rascals Washboard Band 1995 Futuristic Jungleism 4:18

I’ll do another one of just Australian bands when I get a chance. Putting this together I found I had far too many modern bands to include in just 8 tracks, which suggests I should have put this together by theme. I guess the theme is ‘new’ and ‘things I like at the moment.’

french – from france

The other day I was reminding myself that the Les Red Hot Reedwarmers are French – from France – when I suddenly realised:

Holy Shit! This band is FRENCH. So they’re not the The Les Red Hot Reedwarmers, a Jimmie Noone tribute band led by Les(lie) Red! They’re Les Red Hot Reedwarmers, as in The Red Hot Reedwarmers.

It was a freeking revelation. And yet… also a little disappointing.

Btw, if you don’t have this band’s albums and you like Jimmie Noone or early 30s NO-inspired Chicago action, then you’re ON CRACK. Their CDs are really, really good.

rhythm rascals

I’ve just discovered the Rhythm Rascals (c/o the very excellently helpful Peter Loggins) and they’re GREAT.

The site is not.

But I thoroughly recommend picking up a copy of Futuristic Jungelism if you like seriously hot 1930s washboard jazz. It’ll blow your pants off.

8 songs about food

8 songs with lyrics about ‘eating’. And when I say ‘eating’, I mean ‘sex’. Well, mostly. Some are actually songs about food. Probably. But not the Fats Waller ones.

There are approximately 60 squillion billion jazz and blues songs about ‘food’ and ‘eating’. These are only 8, but 8 that I really like, or that we sign around our house, or that are just plain good.

Bessie Smith’s ‘Gimme a Pigfoot’ is the best, because it’s a song about simple culinary and social pleasures – a pigfoot and a bottle of beer. And she’s not going to be payin’ 25c to go in NOwhere.