Update on using gender neutral language in class:

It’s easy.

I like it.

It’s no big deal.

So now I’m taking it a step further. Yes, there is a point beyond gender neutral language.

I find that I don’t like referring to ‘the follow’ or ‘she’ as though they were some sort of universal object or being, while I’m teaching. I prefer to use my teaching partner’s name. For example, I might say, “If I want *partnername* to move straight ahead, then my right hand pushes (gently!) in that direction, and *partnersname* moves that way. What does it feel like for you, *partnersname*?”

I think that this stops me making massive generalisations about leading and following and dancing, and encourages me to think about how each dance is a unique interaction and negotiation of space and time and rhythm and creativity with each partner. Which if course is the point, right? That’s why we go social dancing – to really sample as wide a range of experiences as possible? Or is that just the hippy in me?

I mean, last night we were teaching double top turns to complete noob dancers, and I found myself explaining in abstract terms why you don’t (as a lead) hold your partner’s hand too high above their head: because it’s uncomfortable. I reached a point where I was just annoyed by myself and said, “Look, this is just common sense, right? You’re gentle with your partner and don’t twist their arm behind their back because that’d hurt them? Stay with them, watch out for them, watch them, because that’s the nice way to dance.”

Sometimes we (meaning me) seem to pursue these abstract essential universal qualities of ‘good dancing’ as though they were divorced from the actual humans involved. I mean, the reason why we make sure the follow’s hand isn’t too far above their head isn’t mostly about good technique. It’s mostly because we are trying to stay ‘connected’ (in a social sense) with our partner, and not hurt them. We want to be with them in a personal as well as technical sense. The pragmatics of this (ie where you actually position your joined hands), is a consequence of this recognition that your partner is a whole, complete human. Someone you want to get to know, if only for three minutes. And as a lead, the follow is trusting you to watch out for them. So it just feels like the right thing to do is to justify that trust by not being a dick.

There is no universal, fixed ‘correct’ way of dancing (ie you don’t hold your joined hands an exact 170cm above the ground and 80cm in front of your face). Partner dancing is about negotiating a series of ongoing, constantly changing relative positions and relationships. My partner takes large steps because I take large steps. I lift my right hand higher on their back because they are taller than I am, and than my last partner. I stop dancing like a crazy adrenaline fool, and take more care and pay more attention if my partner is heavily pregnant, or feeling a bit unsure. I begin each dance with some time in closed, so we can get connected and ‘get in tune’. If I feel them disliking what I’m doing, I stop and try something new. I’m constantly alert to the possibility that they might bring something consciously, or that their change in weight or timing might inspire me to try something new. And that I can then integrate that into our dance. This is much more than a conversation (and what a boring, limited idea that is). This is a dance.

And this is why I think I’m happier saying “I do blah blah if I want *partnersname* to do X” rather than “I do blah blah if I want the follow to do X.”

Let’s put the gender back into the description: “I do blah blah if I want her to do X” or “I do blah blah if I want the woman to do X”, then this depersonalising and essentialising is made even clearer. My partner is defined by her/their gender, rather than their role or even their individual personality. And this essentialising discourages you from thinking of all of your partners as unique people, and each dance and dance partnership as a series of compromises, adjustments, active engagements and meetings of mind.

So, you know, adopting gender neutral language is just a tool, or a gateway to much more exciting thinking and dancing.

[An aside]

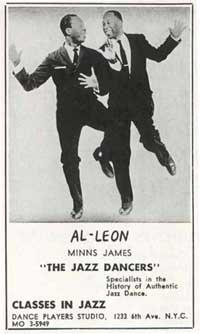

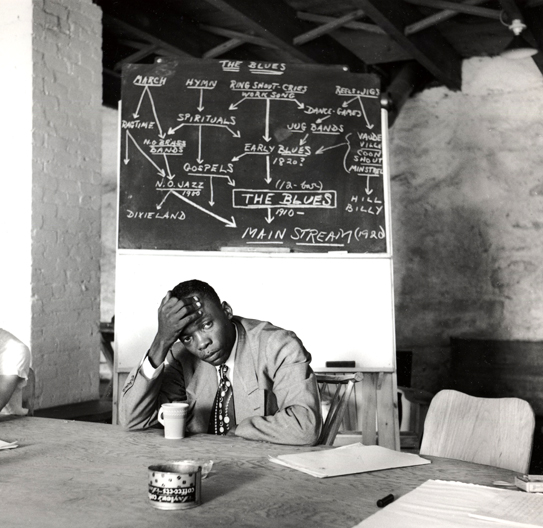

As I re-read this, I wonder if this bizarrely abstract, technical approach to teaching is culturally specific. I’d suggest began in the 2000-2003 period, partly because some people got obsessed with technique, micro-level leading and following, groove (and the slower tempos which made all this possible) and blues dance. And most of these dancers came to lindy hop with no dancing, and almost certainly no partner dancing experience. They also tended to be people from technical or academic backgrounds: IT workers, programmers, etc etc. People who like to logic their way through problems. People who mightn’t (and here is where I make a gross generalisation) have much experience touching and interacting with other humans in a physical way. Beyond sex. So they needed to invent a ‘technology’ for partner dancing.

When if you had grown up with touching other humans, with partner dancing and dance in everyday, normal, ordinary spaces, as part of your ordinary day, you’d be all “Well, durh, if I do this dick like thing, my partner won’t want to be my friend/gf/bf and that’d be crap.”

Now, however, as we move into what’s really functioning as the second or even third wave of lindy hop revival, partner dancing has become so normalised, so much a part of normal life and social interaction, you don’t need to explain every little thing in tiny detail. You can be much more pragmatic and socially oriented.

I mean, one question we get repeatedly from brand new dancers in class is “We did this move, now the handhold is weird – how do we fix it?! [paniiiic!]” I love this question, because the answer is beautifully simple: “If the handhold feels weird, just change it.” And everyone lols, because it’s funny that we’ve gotten so caught up in the mechanics of what we’re doing we’ve forgotten how to hold hands. Of course, the nicest part of all this talk about hand holds is that if you preface all your thinking about hand holds with “Have relaxed, gentle hands, and be cool with letting go of each other,” then you quit worrying about hand holds and get on with feeling the good adrenaline feels.

This all really brings me back to that point: if you’re used to holding hands with people, you’re pretty comfortable with figuring out how to make a hand hold work. But if you’ve never walked down the street holding someone’s hand, or never touched someone casually, or never partner danced, then you are acutely aware of hand holding and are paralysed by HOLYFUCKHOWDOESITWORK!?! panic.

[/aside]

[aside 2]You know why my posts get so long? Because I start writing and thinking, and write as I think, and one idea just prompts another, and another and another, and suddenly the post is a million words long and my brain feels like it on fire with ideas. A long post is the sign of a happy and excited brain.[/aside2]