Here is an experiment with embedding media players. The trouble is, very few of these have the music I’m after. But here’s a Mills Blue Rhythm Band song, in honour of ‘going complete’ and posters on SwingDJs‘ obsession with the band.

E-36992-A Savage Rhythm (Br 6229, 10303, CJM 23, TOM 57, GAPS (Du) 130, Decca GRD2-69 [CD]

Recorded by the Mills Blue Rhythm Band in New York on the 31st July 1931. Musicians included: Buster Bailey (clarinet), Wardell Jones, Shelton Hemphill, Henry Red Allen (trumpet), George Washington (trombone, arranger), JC Higginbotham (trombone), Gene Mikell (sop, as, bar, clarinet), Joe Garland (ts, bar, clarinet), Edgar Hayes (piano), Lawrence Lucie (guitar), Elmer James (bass), O’Neil Spencer (drums), George Morton (vocal), Benny Carter (arranger), Lucky Millinder (dir).

Note: Date used here as given in Storyville #108 (Rust listed date as July 30, 1931).

Brunswick 6119, 6229 as ‘Mills Blue Rhythm Boys’.

Decca GRD2-629 [CD] titled ‘An Anthology of big band swing, 1930-1955’; rest of this 2 CD set by others.

Title also on Hep (E)1015, CD1008 [CD].

Title also on Classics 676 [CD] titled ‘Mills Blue Rhythm Band 1931-1932’.

NB: below are some very preliminary thoughts I’ve had after very little research.

I’ve been spending an awful lot of time in the library lately. It began with the Con’s copy of the Tom Lord Jazz Discography. That’s twenty-odd volumes of dry and boring nerdery. According to The Squeeze. For a jazz nerd, that’s twenty-odd volumes of orsum. I have spent hours in there already. Days. Doing what? Going through my music, adding in dates, full band names, band personnel, recording locations. Extra, extra nerdy. But also quite interesting.

(that’s the Wolverines in the Gennett Records studio from this interesting site)

I’ve gotten much better at identifying when a song was recorded, and I’m getting to know how a band changed or an artist changed over time. And I’m recognising not-so-big-name band members now, which is fascinating. I’m also beginning to be curious about things like travel. A band might have recorded a song on one day in one city, but another song in another city on the next day. This information alone gives you and idea of just how hard these guys worked – travel, travel, record, record, live show, live show. But when you consider the fact that they usually didn’t use planes (in the early days especially) and that segregation meant that these musicians were traveling in pretty shitty conditions…

I’m also interested in the way songs were often recorded only once in a session (or ever) in the early days. No time (or money) for second takes. This makes me think about the mad skills these guys had. Or the cost or difficulty of recording. And all one track as well – everyone just playing along all at once, just recording then and there as the technician heard it.

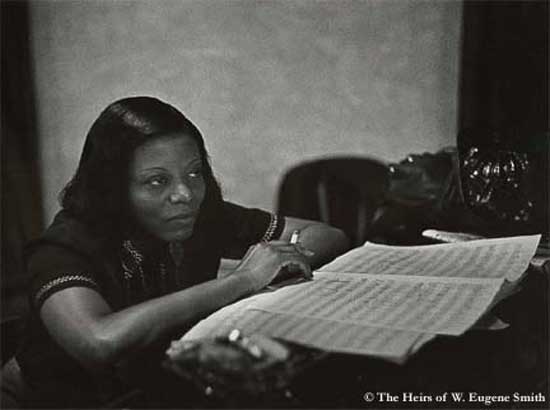

I’ve just come across a quite from Mary Lou Williams (from a book called The Jazz Scene: an Informal History From New Orleans to 1990 by W. Royal Stokes, 1991) where she talks about just how poor Andy Kirk’s band was in Kansas during the depression. The band simply wasn’t getting paid for gigs, so the musicians went days without eating. All that, and they’re still producing truly amazing, inspired music. Or perhaps because of that?

Though the discography is just awesome (and I will continue to make return trips as my need for detail increases – at first dates were enough. Now I need everything), I have moved on. I want to know who was where in what years. Why did people leave a city at a certain time? What was the relationship between the northern migration, Jim Crow laws and the development of jazz in Chicago, New York and Kansas? What was New Orleans like, exactly?

(that image above is of Canal St, New Orleans in the 1920s from wikipedia. If you’re a big map nerd like me, you’ll love this collection of historic maps)

So I’ve been up the university library looking at books. Now, though, I’m thinking more critical questions. How come all the jazz book are written by men? Even the later ones? And what’s the significance of jazz scholarship having its roots in jazz criticism? What role did jazz music clubs (clubs for listeners not musicians) play in the New Orleans ‘revival’ (I’m wary of that term – my thesis has made me suspect a ‘revival’ is really another word for white middle class folk appropriating black culture)? What are the effects of researching a music using only recordings? Where ARE all the women in these stories?

I’m also wondering about jazz scholarship itself, in bigger ways. Where is the critical reflection? What are the effects of research so focussed on autobiography? The emphasis on auto- and biography is interesting; it suggests that some musicians were simply so great, so awesome, so influential, they created in a cultural and social vacuum, simply churning out greatness for the rest of the world to admire. But that simply isn’t the case, of any art; art is created in cultural and social context. So to divorce a musician from the rest of his life (and it is ‘his’ – there are no women here) suggests that the rest of this life was unimportant. As I’ve read recently (and I can’t find the ref, sorry), this lack invites an immediate investigation.

One of the things that comes up time and again in the oral histories of the period is that, for musicians, listening to other musicians is as important as playing. Young musicians (no matter how ‘gifted’) would seek out experienced teachers to learn from. Musicians would spend as much time listening to other bands as playing themselves. There’s this great bit in one book (the one I ref’d above) where the musician describes listening to a band at the Savoy: there were as many musicians as dancers there, drooling over the amazing band (Savoy Sultans? I can’t remember).

And of course, every great musician needed a band. These early jazz recordings are about the relationships between musicians in the band. They don’t – cannot – work alone. In fact, no matter how great one musician, they cannot lift an ordinary arrangement or recording to greatness if the rest of the band isn’t there, or if they aren’t working with the band. At the end of the day, the goal is to produce a great song, a great bit of music. That is the point of a lot of this stuff: it’s about collective improvisation in earlier jazz (where everyone mustwork together – order out of chaos) and about collectivism in the more tightly orchestrated big band swing of the 30s and 40s (where musicians must play together, perfectly, must step in at just the right moment for their solo).

This is of course, all besides the point that being a musician was about earning money to buy food or pay rent. This point makes me think about gender and travel. Linda Dahl (in Stormy Weather: The Music and Lives of a Century of Jazzwomen) makes the point that travel, while so central to the live of post-emancipation black men (who’s right to travel had been so viciously curtailed under slavery) was impossible for many black women. Women, as the carers of children and the aged could not uproot and travel with a band or to become a musician:

It was in the years of elation, confusion and turmoil following the Civil War that jazz began to take shape. The war brought an end to slavery and to the isolation it imposed, which had prevented among blacks the free exchange of ideas that fertilizes art. With abolition came mobility, if not equality. Many black men wandered, looking for work or luck or new vistas, and music traveled with them. But black women, history tells us, were more likely to stay put and hunker down for new roots. These were women who, as slaves, had carried double, even triple burdens. Not only did they work in the ‘big house’ or in the fields – as cottonpickers, eve as logrollers and lumberjacks, – but they of course did their own housework, bore their children and cared for their men. After abolition they were hungry for stable family environments, and it was easier for them to find work as cooks, laundresses or maids than for black men to find employment. Although circumstances dictated that they were often the breadwinners, they deferred to their men, especially in matters political. Above all else they devoted themselves to the hope of better lives for their children. Great were the physical and emotional demands upon them, and most found few opportunities and little time or energy for goals beyond survival (Dahl 1992:4).

For women, cultural and social context was absolutely clear and absolutely present in everything they did. While jazz historians can imagine a Sidney Bechet leaving New Orleans and gadding off to Chicago, New York, Paris, a free agent following his art, it is a little more difficult for them to write the stories of women who played and sang music from the home or the family or their (less romantic) place of work. There are many stories of the ‘whore house pianists’ but far fewer stories of the whores, who were occasionally musicians in their own rights.

Dahl also makes an interesting point about ‘anonymous’ music:

And black women certainly contriuted their share to the development of this music [jazz]. During slavery they made up songs that both drew upon and became part of everyday experience. ‘Anonymous’ was often a slave woman who crooned lullabies to the babies she birthed and the babies she reared, who made up ditties at quilting and husking bees or while she planted in the fields and tended her garden, who created music in her capacity as midwife and healer, at funerals and dances and in church, who developed distinctive vendor calls as she sold her wares. ‘Anonymous’ invented music to meet the occcasion out of a communal pool of musical-religious traditions. Women and men stripped of their names passed on standards and tribel memory to those who came after (Dahl 1992:4).

That point, of course, leads us to a discussion of black women blues singers in the 20s. But I don’t have the time now, and I haven’t read the books I have here. But I was very interested in this link between ‘jazz history’ and race and class and gender. I need more information, though.

This anonymity was the product of domesticity and ‘everydayness’; simply made invisible through its very ordinariness and ubiquity. It was not framed or positioned as ‘art’, and so it was invisible. This reminds me of discussions about vernacular dance. It’s only when it takes to the stage (and away from its mutability and use-value in everyday life) that it becomes visible to mainstream or elite audiences. This is perhaps the greatest problem with reading white histories of black music: these observers could only ‘see’ jazz or black music when it was on a stage, or in a recording, stripped of its everydayness. And these spaces were not accessible for many black women.

Reading jazz as a history made up of one great ‘artist’ after another is, then, highly problematic. I’m also wondering about the other, dominant approach: reading jazz as a history of a series of cities (New Orleans, Chicago, Kansas, New York). What about the ‘territories’ of the midwest, a series of smaller towns and cities strung together on the route of itinerant bands which played only to these towns and rarely (if ever) recorded? Perhaps, as the territories suggest, it’s more useful to think about these cities as sites in a network of ‘jazz place/space’. I want to follow up the idea of travel in early jazz – from the northern migration to individual bands and musicians migrating between cities and countries.

(There are some nice pics in this neat little article about territory bands).

Note: I’ve just found this interesting interview with Tim Brooks, author of Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1890 – 1919. This book is on my list of ‘things to find’. And of course, if you’re interested in the early days of the American recording industry, the David Suisman article ‘Co-workers in the kingdom of culture: Black Swan Records and the political economy of African American music’ is a great resource.

2. Sarah Connor Chronicles is awesome.

2. Sarah Connor Chronicles is awesome.

– it keeps me thinking. Unlike Dollhouse, I’m not prepared to give up on SCC yet; it doesn’t make me so angry I want to scream. It keeps me wondering how it will resolve these tricky relationships.

– it keeps me thinking. Unlike Dollhouse, I’m not prepared to give up on SCC yet; it doesn’t make me so angry I want to scream. It keeps me wondering how it will resolve these tricky relationships.