I’m writing some notes for our students on FB, so I figured I’d let the content free, here in the unfenced part of the internet.

Who?

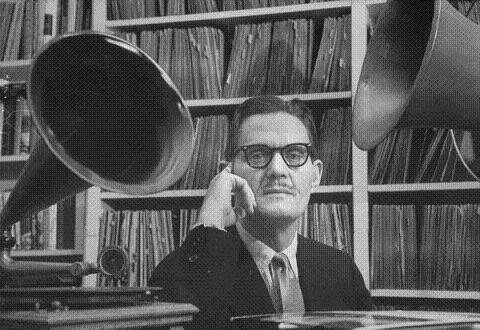

Marshall Stearns.

Stearns was a jazz music and dance historian and reseacher, who was involved in the founding of the Institute of Jazz Studies.

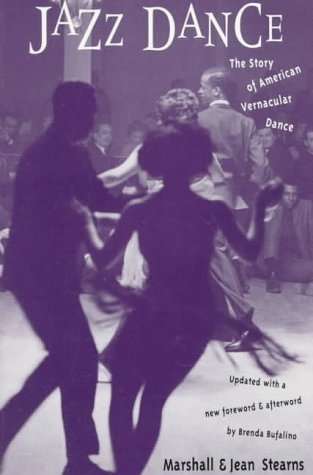

Most modern day lindy hoppers and jazz dancers would know him for his book Jazz Dance: the Story of American Vernacular Dance, which he co-authored (and researched) with his wife Jean Stearns.

Jazz Dance is an invaluable resource if you’re interested in the history of jazz dances (including lindy hop), and it includes extensive interviews, biographies and descriptions of dances. There’s even a section of labanotation in the back, where each dance is carefully described in detail.

But even more importantly, Marshall Stearns features in some of the most useful archival film footage of jazz dance that we have available to us today.

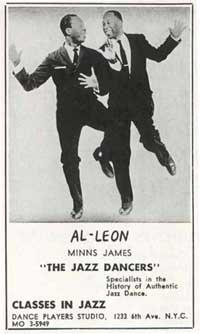

You can see him calling the steps for Al Minns and Leon James in this television program:

Marshall Stearns worked with Al and Leon and other African and African American dancers and musicians, recording their stories, dance steps and knowledge of dance and music.

(Poor John Lee Hooker, workin’ for the man.)

Marshall and his wife Jean, who was also his research partner and co-author, spent hours and hours and days and days working with musicians and dancers, compiling the book Jazz Dance, but also expanding their collection of music, film and documents, which eventually became the Institute of Jazz Studies Archive. They describe this process in Jazz Dance.

Then Marshall (who was a university lecturer and researcher) and Jean set about sharing this knowledge with other people.

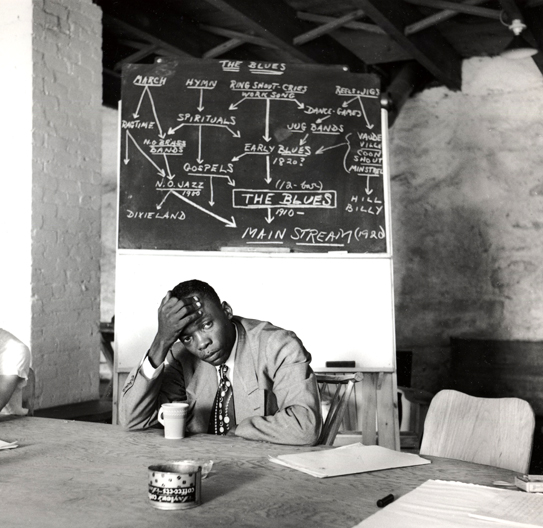

They published books and papers, appeared on television, and were involved in projects like The Music Inn, where (mostly white, mostly rich) people could come to learn about jazz music and dance.

The Stearns write in Jazz Dance:

In the early 1950’s, during the first years of a summer resort in the Berkshire Mountains called Music Inn, we tried an experiment. Our aim was to entertain – quite informally – a handful of guests in the lounge after dinner, but our host Philip Barber was carried away with his theory of instantaneous talent combustion. “Throw gifted performers together,” he said, “get one of them going, and watch them all discover talents which they didn’t know they had.” With various jazzmen of supposedly separate eras, the idea had worked well.

That evening we had dancers from three different countries: Asadata Dafora from the Sierra Leone, West Africa; Geoffrey Holder from Trinidad, West Indies; and Al Minns and Leon James from the Savoy Ballroom, New York City. All of them were alert to their own traditions and articulate, eager to demonstrate their own styles.

So we began with the Minns-James repertory of twenty or so Afro-American dances, from “Cakewalk to Cool,” asking Dafora and Holder to comment freely. The results were astonishing. One dancer hardly began a step before another exclaimed with delight, jumped to his feet, and executed a related version of his own. The audience found itself sharing the surprise and pleasure of the dancers as they hit upon similarities in their respective traditions. We were soon participating in the shock of recognizing what appeared to be be one great tradition (Jazz Dance p12).

The Institute of Jazz Studies holds a collection of recordings of oral histories as well as countless books, papers, music scores and ephemera. You can access some of this online. A highlight is this great biography of Mary Lou Williams, composer, arranger and pianist in Andy Kirk’s band, whose music we often use in class. And you can listen to Nellie Lutcher talking about playing music and traveling on the road in the 1930s and 40s.

Al and Leon continued to dance, perform and discuss jazz dance with Stearns for years after the heyday of the Savoy. Al Minns later worked with the first of the lindy hop revivalists in the 1980s, including Lennart Westerlund.

My favourite part is just after that first quote:

Dafora finally observed with some asperity that although the Fish Tail came from Africa, dancing in the European fashion with one arm around your partner’s waist was considered obscene. (“The African dance,” writes President Senghor of Senegal, “disdains bodily contact.”)

Solo because yolo, right?

While the Stearns rocked the kasbah, I can’t help but wonder how those nights at the Music Inn might have gone if there’d been at least one woman dancing, to talk about African women’s dances, and to demonstrate the badassery that is a woman dancing…

[edit: I’ve just come across this story about jazz education which mentions the Lenox School, which seems an extension of the Music Inn]