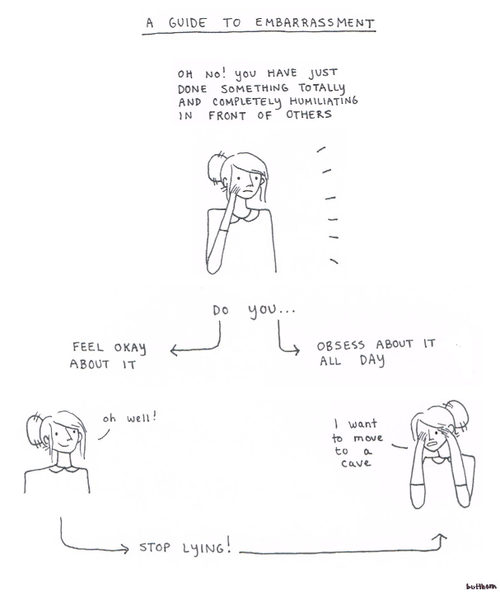

(pic by Beth Evans)

My first instinct, when discovering I’ve fucked up, is to hide the fact. You know, cover it up.

When I was first learning fall off the log, I’d been quite ill with flu, and it was a really hot, humid Brisbane night. I don’t quite know what happened, but everything went black, and I’m suddenly on my arse on the floor. I leap to my feet and carry on like nothing ever happened.

I’m fairly certain that everyone was onto me.

Since then, I’ve made huge, public errors in many ways, and in front of many different audiences. I’ve been the only person in a solo jazz performance fucking up the choreography (I’m usually the only person in a solo jazz performance fucking up the choreography). I’ve sworn loudly into a microphone at a large, public gig. And there was that time when I was at the end of a semester, lecturing for the first time, on my own, pounding out a lecture a week on a range of topics I wasn’t entirely comfortable with. We get to week 10, on The Media In War Time, and I realise, in an exhausted, confused and overworked daze, the night before the lecture, that there hasn’t just been one ‘gulf war’. Furthermore, I have no idea where Afghanistan is, beyond the fact that it’s somewhere ‘in the middle east’. So I go through the lecture and carefully reword things to be precisely imprecise on the geography of the region. I remember, as I’m banging on in front of a group of 200 bored undergraduates, exhausted and strung out on powerpoint, looking up and seeing that row of middle aged women students in hijab making the ‘what the fuck, young person?’ face. Madames, I’m afraid I had no idea what the fuck was up. And I apologise.

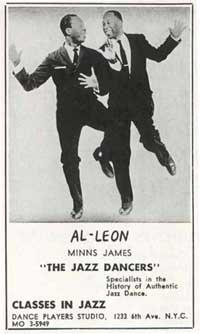

More recently (and most embarrassingly), in fact just this year, I realised that the dancer in this photo that I had thought was Al Minns, was actually Leon James:

Fifteen fucking years of lindy hop, writing and talking about jazz dance, teaching solo jazz and pontificating about uses of history, and I find out NOW that that guy is NOT Al Minns, he is LEON JAMES. Face fucking palm, right?

At the end of the day, though there are really only a couple of ways you can respond to all this. You can leave, immediately, and never look back, retreating to some sort of solo jazz cave in the far western suburbs of Sydney. Or you can quietly continue teaching and crapping on, just with new facts, and never acknowledging your mistake. Who, me, not able to identify one of the most famous dancers of the age? No way, man, I am a SPECIALIST.

But all that kind of sucks. You just carry the shame of mistake around with you, feeling embarrassed and kind of anxious about the whole thing.

That’s all very tempting. But it’s also crap.

This is my preferred method:

Discover the Facts.

Groan. Shout a bit about my own stupidity. Scrabble around, double checking. Get confirmation from someone who Knows (aka a mentor type person whose opinion you respect). Suffer in my jocks for a bit. Then tell people, because it’s both excruciating and also hilarious. There really isn’t anything funnier than pride taking a fall, and usually the circumstances of that fall are totes funny. My general feeling about public humiliation is that it stops being painful and humiliating when you tell someone about it and make yourself laugh.

The freeking middle east, Hamface.

AL MINNS, Hamface.

But what if you are teaching a group of people you’ll be working with every week for the foreseeable future, and you realise you’ve given them wrong information, or you just don’t know the answer? And you’re trying to contribute good knowledge about dance history to your local scene, so we can stop listening to Wham at dances and making up horseshit about lindy hop history?

Probably the most helpful thing I’ve learnt about teaching was in a tertiary education teaching skills seminar, where we looked at the idea of teachers not as reservoirs of all knowledge, injecting it into students heads, but as guides to learning. The students are the ones doing the learning, and our job is to make that work easier for them.

With this in mind, it gets much easier to say, when a student asks a question and you’re flummoxed: “Sorry, man, I have no idea. But I reckon we could find out if we consulted X source. Or why don’t we have a go now, and see how it works?” and then you try that thing, and see if you can figure it out together.

In a dance context, this approach is made easier by adding in an extra element: make mistakes confidently. As Ramona says, a dance class is a laboratory, and this is where we experiment. We are here to try new stuff, and when we’re trying out new things and discovering, there really isn’t any right and wrong. Just various shades of new and interesting.

So what do I do when I discover I’ve taught something that’s completely wrong?

First, I ask myself, ‘Was it all completely wrong?’ Sure, that stuff I explained about the way your hips work in shorty george mightn’t have been strictly accurate when it comes to the mechanics of a shorty george, but was that general approach to biomechanics and rhythm completely wrong? I don’t think so.

Secondly, I remind myself: you are a guide to learning. You’re there to facilitate students’ learning. This isn’t all about you. So you need to stop assuming that they’re all focussed on you. You need to remind yourself, that we’re all there to focus on our own learning, on having fun, and on making mistakes.

Thirdly: just fucking tell them. They really don’t give a shit. They’re worried about the cut of their trousers, or whether that hot person likes them, or if their house mate will have eaten all the bread. They got other priorities. I mean, YOLO, right? Life’s too short to carry around a bundle of anxiety and worry about one tiny fucking mistake. Move on!

In summary, then, I find it both frightening and powerful to approach teaching as thought I will mistakes, and I will be incorrect. That’s the whole point. I’m here to learn too, and if I already knew what I was doing, the whole thing’d be super boring. My goal should be to change and grow and learn as a teacher. Or pontificator.

In practical terms, this is how I handle these things:

- When my teaching partner and I are explaining something, and I just don’t know what I’m doing, I say so.

And I turn to my partner and I say “I’m not sure how to explain this. Do you have an idea?” and they usually do. If they don’t, then we all LOL and we just move on. Yolo, right? And we’re here to dance, not fret about something we don’t know. - Don’t try to make your class a seamless, perfect engine.

It’s actually great to say to your teaching partner “I think we should try this to music, what do you think?” and for them to say, “Mmm, maybe just one more time without music?” It’s great because it takes the pressure off you (you don’t have to be perfectly right all the time!), it models problem solving and partnership interaction for the students (this is how you work on stuff in class with your partner), and it lets the students see how you think about teaching and learning – you’re letting them see the sausage being made. So to speak. You are inviting them in, and not presenting a polished, impersonal facade. - If you find something hard or challenging, you say so. “I find this bit tricky. So let’s go through it slowly, and we’ll figure it out.” Usually they find it easier than I do, which I find very helpful, because I suddenly do understand. And again, you’re modelling helpful learning and in-class behaviour strategies. It’s all good.

- If you teach something, then realise you were all wrong, it’s ok to come back and tell your students.

Sure, it feels like it’s going to be humiliating to admit you were wrong, but dood – you aren’t really the centre of their universe. They’re not going to be crushed because you fucked up that one time. Tell ’em. I do it like this: “You know how last week I said that we start on the left foot/that was Al Minns/Afghanistan is in ‘the middle east’? Well, that wasn’t entirely accurate.” And then I explain what I’ve learnt, and how I learnt it: “I emailed blahblah and got the good oil” or “I compared a bunch of videos and photos from these reliable sources” or “I looked at a goddamn map.”

And then everyone groans, you LOL a bit, and then you revise what you did last week. You can be sure that this particular dance step/conversation/point of geopolitical history will stick in their brains forever. And ever.

…and so on and so on. It’s ok to make mistakes, yo. But it’s not really ok to expect to be perfect, and to not acknowledge your own mistakes. It’s also not ok to stew on your errors and let them consume your thoughts. Dancing, unlike the history of digital media practices in the gulf war, is fun. So let it be fun, and don’t seek out ways to freak yourself out.

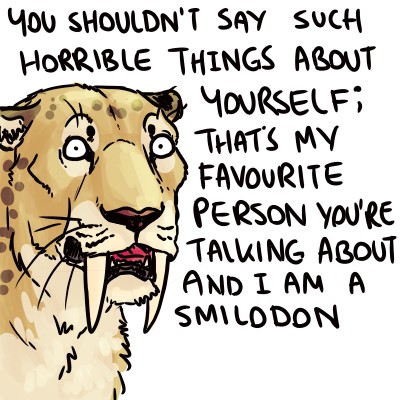

(pic by only fools and vikings via mindlessmunkey)

NB: I spent quite a bit of time on Mindlessmunkey’s tumblr this week, and it shows. The man makes gorgeous, thoughtful internet, and it inspires me.

I love your blog, but this post is even more awesome then ever. I’ve just started a small awkward Lindy class in my city, two ladies in their forties talking about Big Band music and connection and posture to a bunch of bad-asses harcore vegan squatters, and it’s pretty amazing.

Our fear to say something wrong and fuck the hell up in front of them was sometime an issue, in addressing the information and basically killing the fun in the whole process.

Tomorrow I’m going to share your post with my teaching partner and I know we’re going to talk about it for days!

Thank you so much, truly inspiring.

Lucie Q this is a really nice comment – thank you! And good luck with the teaching: jazz dance = the very best way to fight the power, I reckon. :D

Great, great, great x 1,000 post Sam.

Wise words that will definitely help me in my teaching journey.

Thanks a bazillion.