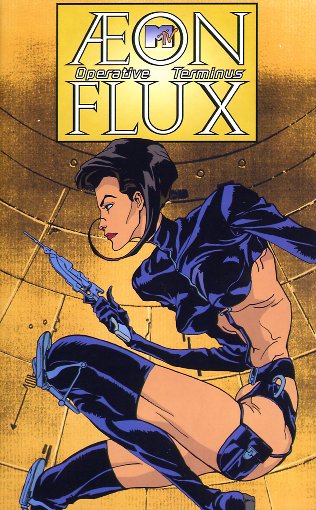

I was a fan of the original television series.

The strange, angular characters and odd storylines really appealed. Not to mention the female protagonist. I liked the way she was ‘sexualised’ but not in a conventionally sugary way.

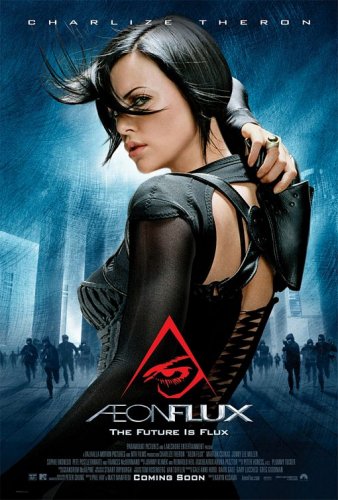

But I also liked the film version.

Watching the extras on the DVD now, there are some interesting things working in terms of body shapes and aesthetics of movement. It’s a very white, European aesthetic at work – lots of pointed toes and extended legs and arms.

But you can’t help but think about issues of gender and body and sexuality when you’re watching an ‘action’ film, whether we’re talking about female or male actors and characters. I was recently seriously annoyed by a comment from a peer about these sorts of female characters – that they were, simply, sexualised eye candy for computer game playing adolescent boys. Because for me, these type of female characters (from Lara Croft to all the Milla Jovovich characters) are exciting and interesting and far more than just eye candy.

I think that my main criticism of that comment is that it suggests that male action characters are somehow not sexualised (because, obviously, the female body is always the object of desire, the male is always the subject). And that a woman being physically active or violent or acrobat is somehow inherently sexual or sensual because she is a woman. And that this somehow mediates the affect of her violence.

Sure, there are some fairly heavily sexualised images in the representation of female action figures.

But then, there are a range of ways of sexualising women and associating them with sexualised symbols.

Whether they’re ‘feminine’

or ‘masculine’

or really ‘masculine’.

But I do think, despite these things, that when the protagonist is a woman, and when she is a powerful character, the phrase ‘sexualised violence’ is too simple. Surely, Charlize is one seriously sexualised body flipping and fighting her way through that film. But the fact that she is a character I feel comfortable imagining myself to be (in a classicly psychoanalitic moment) suggests that there must be some sort of feminist pleasure to be found in these sorts of characters. And that there must be more to them than simply a little hawt body action for teenage boys to scope.

As even my undergrads have well and truly gathered, audiences are active. We make active use of the images on the screen. And so I can make Aeon the type of female character who doesn’t make me uncomfortable.

Aeon herself is an interesting characer, as a result of her original placement as an animated character in an MTV text who died quite regularly.

If you’ve ever seen the original animation, you’d know that Aeon (and her co-characters) aren’t entirely comfortable.

They don’t fit nicely into archetypal ‘objects’ and ‘subjects’. The program was difficult to watch. The characters were difficult to live with.

I know that there are problems with the film. I know that it didn’t bring with it all the subversive and interesting aspects of the animation. But I think that for someone like me, who has seen the animation, the film cannot help but echo the animation – the two are inextricably linked. Intertextual. Cross-polination (to use an image from Aeon Flux the film).

Charlize herself carries interesting echoes of sexuality and the body and speculative fiction.

And Aeon Flux is far less disturbing than silly films like Ultraviolet, though no where near as interesting as Razor Blade Smile.

Did you see that hyper-flexed elbow there on Charlize in that fifth photo? Her left elbow? That’s not good.