The other night we watched the last couple of episodes of The Circuit. It was some of the best television I’ve seen in ages. I even teared up.

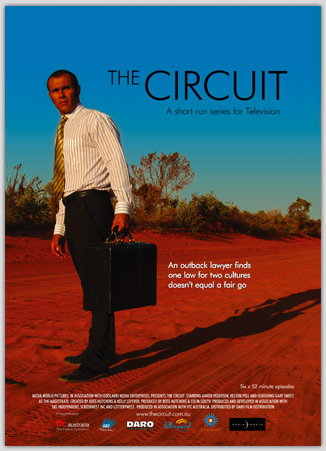

For those who aren’t familiar with the program: it’s an SBS miniseries set in ‘indigenous Australia’. I use that phrase specifically, partly because 90% of the cast are aboriginal, but also because the physical location – the Kimberly – is absolutely essential to the story and look of the program. But this ‘indigenous Australia’ is not an homogenous ‘nation’ – it’s a complicated place peopled by a host of different ethnic and cultural groups, and by individuals with their own specific needs, wants and agendas.

The Circuit is interesting for its location, its stories and simply for its presentation of a ‘legal drama’. But it’s even more interesting for its production: cast and crew were a mix of indigenous and white Australians, the stories were written by indigenous authors. Working and filming with inexperienced crew and cast in geographically remote locations posed particular problems, but also made for stunning visuals.

More prosaically, The Circuit follows a young aboriginal lawyer Drew Ellis as he comes from Perth to work for the Aboriginal Legal Service in Broom for six months. In the very first episode he is established as a child of the stolen generation whose father was taken from his family and disconnected from his land and kin. The program’s story is, ultimately, about Drew’s traveling towards his own cultural heritage. It’s also a story about family and families – the cases heard by the traveling court are almost exclusively domestic stories of domestic violence, property damage and ‘cultural fraud’. These aren’t stories about white collar crime, but about the ordinary crime of everyday life in a community.

The Circuit tells the story of a traveling court – a magistrate, lawyers and police who travel a ‘circuit’ of local communities hearing local cases (and I’m reminded of song lines as I type this). As one of the producers notes in the behind the scenes ‘extra’ on the DVD, The Circuit presents an overwhelming number of cases and people in a very short period of time. There is no time to get to know new cases or clients or stories (not even for the lawyers).

I wasn’t entirely sure I liked the program when I first saw the first episode – the acting was patchy and the camera work and editng were a bit wanky. But really enjoyed the last few episodes. For the most part, these were stories about men – about fathers and sons and men negotiating new lives which accommodated both ‘traditional’ law and Europeam, mainstream Australian law. This law dealt largely with violence – with men’s violence towards women and to other men, and with the effects of violence on grown children – men who had been taken from parents, men who had been sexually abused. These men were, for the most part, aboriginal, but not exclusively so.

One of the most touching parts of the story involves Drew’s efforts to locate his father’s extended family. He’s initially and continually unsure of the project – his colleagues and friends encourage him, making the point that it’s ‘important’. His white wife, while ambivalent, is, essentially, also encouraging. But Drew becomes increasingly reluctant to seek out and make contact with his family. This was the part I found most moving – he was afraid and nervous and excited and afraid again.

As a middle class city boy moving to the bush, he was confronted by the social reality of aboriginal communities in the region, understandably challenged by the crime and violence and effects of white invasion. But he was also tempted and seduced by the importance of family in the lives of his aboriginal friends – Bella’s large, welcoming family; Sam’s place within a complicated network of family and friends. I really liked the way Drew’s mixed feelings were dealt with in the story – he obviously wanted, quite desperately, to find a place in this extended community. But he was also afraid of what he might find and what it might mean to dig in deep and commit himself to staying and living in the region. When he asks Sam to explain the exact terms of his relationship to recently discovered ‘cousins’, he’s obviously attempting to map, precisely, his place in this family, his role and responsibilities. But Sam repeats: “They’re cousins on your dad’s side,” and that’s enough – clearer definitions of exact genetic relationships aren’t important. What is important is that he belongs to ‘that mob’ and that they belong to him.

As a middle class city boy moving to the bush, he was confronted by the social reality of aboriginal communities in the region, understandably challenged by the crime and violence and effects of white invasion. But he was also tempted and seduced by the importance of family in the lives of his aboriginal friends – Bella’s large, welcoming family; Sam’s place within a complicated network of family and friends. I really liked the way Drew’s mixed feelings were dealt with in the story – he obviously wanted, quite desperately, to find a place in this extended community. But he was also afraid of what he might find and what it might mean to dig in deep and commit himself to staying and living in the region. When he asks Sam to explain the exact terms of his relationship to recently discovered ‘cousins’, he’s obviously attempting to map, precisely, his place in this family, his role and responsibilities. But Sam repeats: “They’re cousins on your dad’s side,” and that’s enough – clearer definitions of exact genetic relationships aren’t important. What is important is that he belongs to ‘that mob’ and that they belong to him.

I think it’s this point of reciprocity that was most moving. An older man, Jack, sees Drew at a trial in a remote community and mentions “I knew your grandmother’s family”. Drew is confused, stunned, unsure: could finding his father’s stolen family simply be as simple as being ‘seen’ out in the community by a member of this extended network? He asks his friend Sam for his advice: “He reckons he knows my family,” and his friend encourages him to seek them out. From here, Drew begins to both seek out and avoid learning more. The part I liked the most, though, was the way that Jack decides that he won’t let Drew disappear. Jack turns up again, later, at another court session. Drew asks him what he’s doing there: “I’m waiting.” He’s obviously waiting for the younger Drew to be ready to explore his family. To be ready to take on the emotional weight. To be ready to commit to the broader community of the region as a lawyer, as a man, and as a member of a family. The Jack follows Drew back to Broome, and eventually Drew decides that he’ll commit to another six months in Broome with the ALS, and more importantly, to seeking out his family.

The part of all this that I really liked was the older man’s patience. He didn’t badger or attempt to bully Drew into coming back with him to meet his family. He didn’t argue or attempt to convince him. He just waited until Drew was ready. Sure, it was an awesome display of passive aggressive manipulation, but more importantly, this older man’s waiting and simply being visible and present in the life of a younger man who lacked connections with family and elders was a key part of the narrative generally. This is played out in Sam’s relationship with his estranged teenaged son. Sam ultimately chooses to reenter his son’s (and wife’s) life, and spends hours one night waiting for the son’s drunken anger to wear down so he reestablish himself as a father.

I liked this emphasis on patience and waiting. I liked the way it wasn’t a story filled with ranting, American style exposition. There was a lot of quiet patience, younger men being waited for, and older men learning to wait. I also liked the way Drew’s story wasn’t just one his father being ‘stolen’ and then ‘lost’, beyond the reach of his family. I liked the way it wasn’t a story just of a man returning to his country to find his people. I liked the way it was a story of a family and a people – a community refusing to let children be lost. I liked the way this older man took on the responsibility of caring for Drew, and of refusing to give him up. But in a quiet way. I like the thought of a family refusing to let its young men disappear or walk away from their place and community. I liked the idea of a community having responsibility for its members, as much as the members have responsibility for their community. In fact, I like the way the distinction between ‘individual’ and ‘community’ was collapsed. The more time Drew spends in the region, the more people see and recognise him, the more firmly he is established as a part of a complicated network of people and place. Eventually, he can’t exist outside this network – he learns to work in the community more efficiently as a lawyer, but also as a son and cousin and part of a wider community.

I also liked the way Drew’s response to all this was ambivalent – he had to negotiate his own acceptance of this new life and new family. Sure, it was inevitable (and you get the feeling that his family were never ever going to let him completely cut himself off again – they’d found him and were keeping him), but his own active negotiation and acceptance was also essential.

I also liked the way the local community reached out to newcomers to find a place for them in the extended community network – the older European woman Ellie is sitting at the beach with a group of women teaching and learning a dance for an upcoming festival. The older women tease her about her reluctance to date an older aboriginal man who’s been flirting with her. The woman who’s been teaching the children the dance says at one point, after demanding they do it again until they get it right: “We could use more dancers,” looking at Ellie. Ellie makes an excuse and leaves the group. But it’s clear that she’s being invited to join the dance not just as a way of including her in the group, but as a way of including her in the wider community network. It is as important to the community (and dance) to include her as it is to make her feel ‘belonging’ or ‘included’. It reminds me of the way white researchers in remote aboriginal community speak of being given a skin by the local community – it is important for them to have a place so that others in the community know how to deal with them and interact with them. Because there’s a system of rules and law dictating how people should and do interact with each other, and with the land.

So The Circuit is, mostly, a story about a community finding a ‘skin’ for Drew – a way of integrating him into the community, into the system of respect and family and land and law. It’s also about his finding a place for himself, but its more important for him to understand that he is also being claimed and found in return. He belongs to that community as much as it belongs to him.

[all images from here]