[Look, friends, this post is quite long, and not as well edited as it should be. But I have very little time to blog at the moment, so I just tried to get it all down this afternoon while I had time. If I can, I’ll look through it and edit it more to get it tighter.]

Speaking to a musician friend the other day, about possibly doing some collaborative projects, I realised we had a fundamentally different idea of live music at a gig.

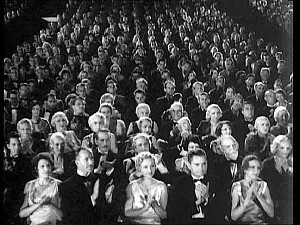

He was thinking in terms of performance: where the band get up, play some songs, do some creative work, and the audience meanwhile sit and watch attentively, ‘receiving’ the message broadcast by the band. At the end, the audience claps, the band feel celebrated, we all go home.

I was thinking in terms of participation. The dancing is the main thing, and the music is a part of that thing. Instead of sitting quietly, the audience are actively engaged with, and in a collaborative creative process with, the band. The band is making the sound, the dancers are making the sound visible. And even within that collaboration, the dancers are interacting with each other as much as – usually more than – with the musicians. As a simple illustration, dancers rarely even look at the band while they play the song. It’s only when the song is finished, the partner hugged or thanked, that the dancers look up at the band and applaud them. Even then, there’s this feeling that the dancers don’t so much want to ‘applaud’ the band, as hug them too, as everyone has been working together to make these feels.

Everything that I do as an event organiser in the dance scene, is about getting everyone in the room involved and engaged. I don’t just mean up and dancing – I mean up and emotionally engaged with the music, with the musicians, and with all the other people in the room. I do this partly because I’m a big hippy, and I feel that everyone is important. I do this partly because the more people participating, the bigger the feels – the room just ‘feels good’ when there are more people out there, feeling good. And I like how that makes me feel.

I think my practical approach to this comes, fundamentally, from my DJing: I am not satisfied with filling the dance floor. I want everyone in the room, whether they are dancing or not, to be feeling feelings that come from the interaction of everyone in the room with the music. And this engagement is active. Yes, there are times when you do sit (or stand!) and give the band 100% of your attention, not even bothering to dance. But even in those moments, you are actively engaged.

I can’t help thinking about the way audiences are positioned in anglo-Australian, middle-class ‘arts’ culture, compared to African American vernacular culture. In the former, the audience sits and passively ‘absorbs’. They’re silent throughout the performance (except for the odd applause for a solo). They don’t fidget, they don’t say anything, they face the front (the stage and musicians). That fourth wall, dividing the audience from the performer is made of cast iron and concrete.

In the African-American vernacular setting, the audiences are engaged with the performers. The performers invite that engagement: there is a call to which audiences must respond. How do they engage, or respond? This isn’t a free-for-all. There are clear guidelines or rules (of social nicety at least) which determine how you – in the audience – engage with the performers, and this is something you learn by being there, a part of the crowd, with your family and friends.

Ok, this is something I feel a bit weird writing about, and I do think the following clip is a bit of a cliche and the Blues Brothers is not without some serious problems in its depiction of race and class, but it makes the point in huge, big, neon colours:

(Do You See The Light – Blues Brothers (feat. James Brown))

The thing that’s important to note here, is that the audience is responding to the ‘minister’ (aka James Brown) and his commentary, physically and vocally. This works much the same way as non-verbal/collaborative commentary in a conversation does: when your friend tells you a story about that arse boyfriend who’s been fucking her around, your job is to say “no!” “fuck OFF!” “for real?” It’s totally ok (if not required) to interrupt and add vocal commentary. This commentary doesn’t derail the conversation, it signals your empathy, that you’re listening, and that you need to hear more. You don’t interrupt with “Oh yeah yeah I’m going to the shops tomorrow,” you interrupt with “what a bastard!”

The speaker/performer leaves pauses, which work as an invitation for commentary or response. But they might also directly ask for a response – just as Brown asks “Can I get an amen?” at 1.45 in that video. Usually all this interaction and call and response is carefully managed by the minister/performer to work to a climax – a moment of heightened feelings and group engagement. In the Blues Brothers clip, the climax is where one of the brothers is so moved by the service he enters into it, physically, dancing.

As a service or performance continues, this gradual build to a climax, and then slower decline and shift into a quieter, more introspective moment, then gradual build again, each crest reaching a little higher, each trough not quite as low as the one before, is all carefully managed to build people into a frenzy – an ecstatic moment. There’s something about the combination of music, dance, and being in a group of humans all sharing the same feelings that magnifies the experience.

Any lindy hopper knows, that when you’re in the middle of this, it’s the best, most amazing feeling ever. You lose all your inhibitions, your move your body like a crazed fool, and – best of all – it’s all totally ok and sanctioned by the community. Everyone in the room is ok with you being swept up by your adrenaline and good feels on the dance floor. It’s heady, it’s powerful, and it’s addictive. Bands who get engaged with the dancers and participate in this group feels find that it makes them feel really good, and the music feels better.

James Brown, of course, had been doing this for years. And as the epitome of an egomaniac, he understood that being the focus of all that group ecstasy feels good. Really, really good.

James Brown -Soul Power – Zaire 1974

Jazz music is rooted in black communities, and in gospel, work songs and the blues. The blues most of all. All these songs happen in everyday community places: churches, workplaces, bars, homes, community halls, dance halls. Call and response is central to all these. The expression of an emotion or an idea, and then an invitation to comment or engage with that idea, is a central tenet of vernacular music. This isn’t a great artistic statement made by a great artist, to be hung in a gallery or admired from afar. It is a conversation, and if it isn’t useful or accessible, it’s going to fade away.

Blues in particular requires a call and a response.

Bessie Smith singing St Louis Blues

This is a good example (in a pretty stylised way) of what Albert Murray called ‘stompin’ the blues’. You’ve got bad, low down feelings (you have the blues). Instead of hiding away in your house, you come out to share your feels with your people. You sing about the awful stuff that’s been happening.

This is a good example (in a pretty stylised way) of what Albert Murray called ‘stompin’ the blues’. You’ve got bad, low down feelings (you have the blues). Instead of hiding away in your house, you come out to share your feels with your people. You sing about the awful stuff that’s been happening.

The bit that makes the blues so excellent, is that they don’t have to be sad songs. The performance of the song, as well as the words and music dictate the ‘proper’ response.

But this participatory model is not what most modern Australian jazz musicians expect or look for. Or even really imagine when they put a gig together. But Count Basie was on it:

(Count Basie Orchestra with Joe Williams, ‘Every Day I have the Blues’)

In that performance (which was pretty much a schtick by that point), Joe sings out “Nobody loves me. nobody seems to care”, and then he pauses, and the band respond: “Awwww!” And this is repeated. Here in Sydney, the Basement Big Band do a great version of Every Day I have the blues. And when it gets to that part of the song, there are dancers who’ll yell out “Awww!”, especially if they’ve been around a while, and heard Basie’s version of that song a million times.

But almost every time that band so that song, they seem surprised when the dancers yell out – when they respond to what is essentially a call for sympathy.

“Nobody loves me. Nobody seems to care.”

“Awww!”

I guess the difficult part of this performance is that the call and response in this song is largely taking the piss. The line “Nobody loves me. Nobody seems to care.” is a bit rich coming from a singer standing in front of a big band on a stage in front of hundreds of people. Obviously we do all love you. And we do all care. So the response: “Awwwww” is taking the piss. It’s sarcasm. And there’s the LOL.

Albert Murray goes into this in detail in Stomping the blues:

…in the performance of a blues ballad the chances are that even the most solemn words of a dirge will not only be counter stated by the mood of earthy well-being stimulated by the beat but may even be mocked by the jazziness of the instrumentation.

…What blues instrumentation in fact does, often in direct contrast to the words, is define the nature of the response to the blues situation at hand, whatever the source. Accordingly, more often than not, even as the words of the lyrics recount a tale of woe, the instrumentation may mock, shout defiance, or voice resolution and determination (Murray 68-69).

So I guess a young guy singing that line, which he’s only read on paper or heard someone straight like Frank Sinatra sing, isn’t going to be familiar with the history of live performances of the song, or with the to-ing- and fro-ing of blues music. When Frank Sinatra sang all those crooners, the band was just background for the ‘artist’. When Joe Williams sang with Basie’s band, he was just one more musician in a crowd. This band were his peeps: they had is back, they travelled with him and slept with him and ate with him and argued with him and drank with him. Of course they cared. And just like family, they’re going to take the piss out of him and tease him. But no one teased Mister Sinatra. Especially not when he was playing for a polite white people crowd in a polite white people venue.

These layers of meaning that happen when a song is performed live, to real live people is important to jazz dance. Even to modern day lindy hop. I can think of a million examples of dance competitions or performances where dancers have used ‘straight’ steps to imitate someone, to mock someone, to thrown down. This is the history of jazz dance, and the way any vernacular dance works: the lived, immediate context of the performance shapes the meaning of that performance. And the way the ‘audience’ engages with that performance actually contributes to the construction of that meaning. Not only is jazz exciting when it is collaborative, it is at its most powerful and subversive.

Industrial difficulties: a swing DJ working with sound engineers.

I have to work with music industry professionals quite often, and they have all been men. The only exceptions were that one time I did a few gigs at the Speigeltent, and there the women I dealt with were managers, not sound engineers. I have worked with some women musicians, but very few. This is a male dominated industry, and more importantly, this industry is innately patriarchal and sexist. I know some people have been arguing lately that the lindy hop scene is sexist. I actually disagree with this. I think that there are some dodgy elements in our culture, but if you want real sexism, and real patriarchal discourse and patriarchal control of creative practice, you should check out the live music scene in Australia.

As a lindy hopper, and as a DJ, I imagine an ideal live music gig as one where everyone in the room is engaged, and there are a whole heap of things going on in the space contributing to the good feels going on. This is very socialist feminist of me. But it’s about creating powerful creative experiences.

In the last two weeks I’ve done a few more gigs than usual in non-dancer-run live music spaces. I did some teaching and a bit of band break DJing at a regular live music event which is targeting dancers, but run by a live music venue. And I did some band break DJing at a live music event which was part of an arts festival, and was targeting a combination of dancers and ‘normal’ people. In both cases, none of the organisers, sound guys or even musicians were lindy hoppers, or even really understood what a successful live music event for lindy hoppers involves. I’d say that both were quite fun, quality events. But I’d also say that these were very conventionally gendered spaces, with very traditional distributions of power, valuing only certain types of knowledge.

When I DJ band breaks, I see my job as having these key parts:

1. I warm the room for the band, before the band starts. So the band don’t start playing to an empty room. They start playing for a room where people are already dancing and having fun. This is a bit like making sure that every band is the headliner, playing after the support act has warmed up the crowd. But I don’t ever let that energy peak or reach climax – the room must feel as though we are building to something, expecting something.

2. I complement the band’s work, but I don’t play the songs they play, and I avoid hi-fi badarse versions of the type of music they play. Because modern day bands just aren’t going to be as good or sound as good as Basie in 1957.

3. I keep people dancing during band breaks, to keep their energy up. This is because if you let dancers sit down between band sets, their adrenaline will ebb, and they’ll suddenly realise just how tired they are, and then they’ll go home.

At both these gigs this fortnight past I was struck by the differences between my approach (where I am working dancers to set things up for the band) and the sound guy’s approach (where he sees himself setting up a crowd of listeners for a band’s performance). At both gigs, the sound guys insisted I:

– play only a quiet song or two after the band was finished

– leave lots of quiet time with no music playing after the band finished a set

– not play any songs before the band began

– keep the band break music minimal.

In both cases, when I suggested otherwise, both sound guys were really, really patronising. I felt like shouting: “LOOK, FUCKERS, I KNOW DANCERS AND I KNOW YOU’RE WRONG!” But I didn’t, because that would be silly. And it actually took me a while to figure out that there were profound differences in the way we were perceiving what was happening around us. While both those men bullied me into doing what they wanted (in one case to the point of directly disobeying instructions from the venue manager), I took the traditionally feminine path of avoiding conflict. Life is too short to argue with dumbarse sound guys, my friends. Particularly as they all seem to have seriously damaged hearing.

At the first gig, after the class and before the band began, there was about 30 minutes of silence. This was weird, and, I felt, a real error. All the high energy and good vibes of the class just dissipated. All the new dancers suddenly realised they’d been doing aerobics for an hour, and lots of them went home.

I’d have gone straight to the band, so the students didn’t realise they were exhausted.

After a band is finished, I like to just end all the music, completely. That way the band ends on a high, and we make it clear that they are the highlight, and when they’re done, we are done. But when you play a few quiet songs, lindy hoppers keep dancing. In a regular live music gig, that quieter music signals ‘clear out time’, and people stop dancing, find their shit and go home. Dancers, however, will squeeze every last minute out of an event. So you have to stop things clearly. You also have to allow for the fact that they spend that hour immediately after a band ends talking and riding their post-dancing feels, because they haven’t had a chance to talk all night. So they won’t piss off, ever, unless you stop the music and raise the lights.

In band breaks, if you leave the break too long, and the dancers without music and dancing for too long (especially on a week night), the dancers stop dancing, their adrenaline trickles away, they figure out they’re tired, and they go home. Which is what’s been happening at the first live music gig over the past few months.

In all these cases, there are a lot of things contributing to the success of the night for dancers. The band is just one part. If my band was called ‘Sam’s Hot Shakers’, and I had a gig, then that gig’d be a ‘Hot Shakers’ gig’. But if I run a dance with the Hot Shakers playing, it’s not called ‘The Hot Shakers Dance’. It’s called Sam’s Dance. And only later do people ask who the band is. What’s important is the whole package, including the music, not just the music itself.

The challenge then becomes: do you pitch to the dancing crowd, or to the non-dancing crowd? Do you pitch to both, and if so, how the actual fuck do you pull that off? In the latter case, I’ve found that the crazed energy of a lindy hop crowd actually sucks the non-dancers in and drags them along against their will. In the former case, the dancers crash and go home.

This is relevant to this post (rather than warranting a post on its own), because these ideas that the sound guys’ had are dependent upon that very boring idea of audience and performance: music is art on a stage, and audiences must stand/sit and watch. Sure, they can dance, but their dancing isn’t ‘art’ in the same way that the band making music is art. In this setting, art is made by ‘artists’, not ordinary people, and art is cordoned off by the limits of a stage. And by band breaks.

The thing that makes me lol is that this idea dominates most live music, even in venues where the music is quite ‘counter culture’ or ‘alternative’. And the guys policing the sound are all macho blokes, and the people on stage are mostly blokes. It’s the most conservative demonstration of gender and culture you could possibly imagine. Status and power are so rigidly policed they might as well be running a rugby league match.

This is what I’m a bit surprised by: if you were a musician, wouldn’t you get off on being the focus of an engaged, active audience? I guess not, if you weren’t used to this different model. It must sound and feel a bit like chaos, like rudeness if you can’t see the patterns. A bit like being in the crowded fruit and vege shop up in Ashfield: you have to relax and gently push your way through, trusting that everyone around you knows that you’re all just chilled, getting your veggies and ok with the close proximity of other humans. And just like the odd middle aged middle class white woman in the shop, if you’re faced with apparent chaos of a unscripted, participatory live music gig, you might freak out a bit. Or just not know what to do or how to do it.

What is it like when a band and a crowd of lindy hoppers all get on the same page and make it work properly?

Now I’m going to do a long analysis of what I see happening in the DCLX 2011 band battle video. I’d be curious to see what’s happening in the music, from a musician’s perspective. I’m watching as a lindy hopper, and as a DJ. And as I watch, I’m caught up in the feelings. It’s making all my muscles fire. This is how I feel when I’m DJing and really right there with the dancers, feeling what they feel, even though I’m not actually dancing. It’s a physical experience: my heart picks up, I sweat, I get wide-eyed and hyper-stimulated, I jiggle, my muscles jump. It’s the pavlov’s lindy hopper effect, and it’s almost as good as actually being out there dancing myself. It’s also like crack cocaine. And massively addictive.

I keep using this example because it’s so powerful, and so usefully documented in the attached blog posts. In bands for dancing I linked up a few posts (written by musicians who were there) and clips centred on a battle of the bands at DCLX 2011. Here, watch this video, where two bands trade (blocks of) phrases in a battle.

Firstly, the audience is NOT silent during this song. There’s some talking, some shouting, some clapping. This is obviously partway through a gig, when the room is well warm, and people are feeling their feels.

The song – Basie’s 1937 arrangement of Honeysuckle Rose (with some adjustments by the bands playing it) – is the perfect lindy hop song. It’s the right era, it swings like fuck, it’s full of energy. It also starts off kinda quiet and chilled, then it BUILDS and it BUILDS until you asplode.

The best part of it is that the iconic Honeysuckle rose melody (would you call it a riff?) is introduced lightly, then it takes a back seat as the rest of the band brings it FULLY. I guess the thing that makes this song so powerful for lindy hoppers (and jazz fans?) is that it begins with that melody that we associate with Fats Waller and smaller groups, then spreads it out and really pumps energy and layers into it with all the power of a classic, swinging big band.

This is nice for a battle, because it starts us off with a mellower base line. Then it gets HOT.

Other things I like about this clip:

The band leaders talk to each other during the performance, sorting out who’ll do what and clarifying bits and pieces. But there is some serious rivalry here: this is a real battle. Jonathon Stout has been playing for dancers for years and years, but watching this clip, you get the feeling that the band (on the left) isn’t really into what’s going on. They’re complacent, perhaps? The blog post by the clarinetist in the band certainly suggests it. Solomon Douglas on the piano is a dancer (and used to do a duo act with Gordon Webster, which they brought to Australia in 2002), and you can see his massive brain leaping about, making connections.

Glenn Crytzer’s band, on the right, was (at the time), the latest hot thing in lindy hop – headed by a dancer, and a band leader with close connections with dancers and the dance scene. Crytzer has always felt to me like a particularly ambitious man, pushing to make his band more popular and more successful. This is, of course, exactly what you need in the entertainment industry: you have to push push push. But this band feels like they are there in that moment, ready to rumble. They haven’t been doing this as long, but they’re also talented, and they feel hungry. They are READY.

The musicians in the band interact with each other. While the young bloke in Crytzer’s band plays his sax solo, Glenn and the woman in the row behind exchange grins as the solo KICKS it. And the Glenn blows on the sax (miming that the solo is so hot it needs to be cooled down), the woman grins and the dancers and audience laugh. This is a nice little moment of active engagement with the music, the musicians, the audience. Sure, it’s mugging on Glenn’s part, but that’s also fun and funny. And when everyone’s caught up in the feels the way they are in that moment, people don’t mind it – they kind of like it. And when the solo ends, everyone cheers (in a real way), the other musicians around him grin and solute him with a nod, and then it’s over to Stout’s band. A challenge, if ever there was one. The sort of bold bravado that young men do really well.

I like it then, that everyone in the room is all ‘ok, Campus Five, bring it’: they believe the band can match that hotness, and they’re urging them on.

Then we hear a cheer. On the other side of the stage, out of camera, someone is pulling out a sousaphone. This is total grandstanding stunt musicianship. That sort of instrument is totally mouldy fig pre-swing cheese. But it was (and is) totally hot with dancers. It distracts the audience from the opposition’s solos, which is legit: if they’re not hot enough to keep our attention…

And then the solo is great. It’s all cheese – the banjo, the sousaphone, the trombone. And it’s just great, because it’s bold, it’s brash, it’s a shameless bit of grandstanding and pandering to the audience, but the shift in rhythm is exciting, it’s a clear call to the roots of jazz, and the band is right there with Crytzer (watch the faces of the drummer and sax player): they are totally calling the other band out. As a dancer, this is like pulling out a stunt step – a stupid-crazy arial. Or doing three hundred swingouts in a row. Or diving into the audience to crowd-surf.

In terms of call and response, this moment is great because the audience respond not only to the act, but to the way the band feel when they pull this out. They respond to the audacity and bravado. They delight in the ‘risk’ (it could have fallen quite flat), and to the fact that the band is really bringing some shit.

Watching Stout’s band respond is interesting. There’s a sax player in a white jacket who’s almost hiding. It’s like he’s finding all the braggadocio uncomfortable. The closer they are to Crytzer’s band, the more engaged the members of Stout’s band are. It’s interesting how this ‘turn’ and then Crytzer’s response work as a ‘trough’ in the energy. We peaked with the sousaphone, now we have to recover. These moments of recovery are important. Our bodies can’t physically handle more than about 12 or 15 minutes of extreme stimulation (whether anxiety or fear or rage or ecstacy), and by working a ‘wave’ in energy, that state of stimulation can actually be extended – so rather than working at peak stimulation for 15 minutes, the stimulation is scaled up and down to sustain the energy and feel over all. But even the troughs in the middle of this song are resting at a higher energy level than before the song began – the overall energy level is higher than before.

At about 3.42, we feel a little kick. It’s that repeating bit of tune (fuck I wish I knew what the technical term is) that suddenly adds layers. Repetition is important – without repetition, the punch line isn’t as funny in a joke. So when three men walk into a bar, an English man, an Irish man and an Australian, what’s most important (and makes the joke work) is that there are three men. And it’s the repetition that builds suspense (and anticipation), with the pay off in the final repetition. And that final repetition is where things are changed up – our expectations are met (and exceeded) and the tension released.

For dancers, the same effect can be gained by repeating an 8 count step three times, then switching to a different step on the fourth (in a 4/4 4 8s per phrase structure). Three swing outs then a circle with a seven-stop has the same effect. And something about it just feels good. Dancers watching this battle and listening to this song are really good at recognising and creating these patterns: so our engagement with this music is not only in terms of intellectually and aurally recognising the patterns, but in terms of remembering the physical experience of making those patterns. And because we are pavlov’s lindy hoppers, we physically re-experience that pattern at the same time we hear a new one. Layers and layers of meaning are happening here.

At 3.50 Crytzer hands it back to Stout, and this is really a real present. The energy has just been rebuilt after a little lull, so the crowd has replenished energy and is ready to climb to a peak again.

[This is a little like something I did DJing on Friday: I slowly built the energy up in the room over about 5 songs, heading to a performance by a troupe at about song 6. I tried to build the energy and sustain it, without climaxing before the troupe. Luckily it all worked out ok and the troupe were ready to go just at that moment of climax. Any longer and the crowd would have had to start down again as their bodies and feels began to plateau and drop down from that climax. Of course, following up from that sort of performance with the band playing a high energy, medium tempo song is the perfect way to totally pwn the crowd. The problem, of course, is that not many bands are paying attention to that vibe, and they can’t read what’s happening in the room. The band on Saturday were almost in the right spot, but not quite.]

Watching Stout, it’s like he’s trying to physically will the band to that point of climax. But it’s as though the band just aren’t feeling it. They look whipped, like they know they’re pwnd and have given up. They do, though sustain the energy (just), which Crytzer’s trumpeter just picks up and runs with, then hands to the drummer. It’s like that band is right in the feels, and riding that wave.

Mind you, a trumpet-drummer shared solo is pretty much gold for a band leader working a crowd: dancers like rhythm, and a trumpet brings the ecstatic highs – the extended, lung-stretching breath that just keeps going. That’s pretty much how the best fast lindy hop feels: the rhythm just grabs you (that’s your pumping feet, your pounding heart), and you think you might die of suffocation because you’re past breathing hard and into serious shortness of breath (which of course makes you see the appeal of auto-asphyxiation, right?) and then the trumpet is right there, combining the ecstatic high of joy in speed and movement with the strain of a breath held too long.

Then Stout’s drummer just fucking throws all the pots and pans down the stairs and it’s fun. I feel, at this moment, it’s as if all the parts of Stout’s band are really, really good, they’re just not together as a team, feeding on each other’s energy. I want to say to the guys in his band, “Hey, see how Crytzer’s band are standing up? You need to stand up, so you can start your feels with some jiggling about and adrenaline.”

I do like the next to-and-fro between the clarinetists. It’s like a sophisticated exchange of barbed wit after all that drumthuggery.

At 7.00 when everyone comes together in that repeated theme (and you can hear people singing along), it’s just so exciting and great – that’s the moment before the punch line, when you know something’s coming, and you know it’s going to release all that tension, but this moment, right here, where we are all together, is just good. And I think that – as lindy hoppers – we are naturally inclined towards enjoying moments of synchronicity and harmony. That’s Frankie Manning’s legacy.

And then at 7.24 it all just comes together and we ride it home.

You can see, in this video, all the call and response stuff, all the repetition, building of energy, collaborative interruption between audience and player that really shifts a live music event from passive audience to active audience. I feel that it is in these sorts of events that musicians really connect with audiences, and with the music itself. Because this music was designed to be dance music. It’s pop music, it’s mass-produced, it’s highly formulaic. But the great strength of jazz is the way it combines the rigid confines of formula with creative innovation: yes, a blues song has a clear AABC structure, but there are moments between each line where the band can just improvise and make shit up. Sure, Honeysuckle Rose is the most standard of standards, but the very familiarity of its formula give the musicians a shared, common ground from which to begin. And when they’re done innovating and improvising, they come back together as a group to reinforce the shared value of the thing.

This video really captures a successful musician/dancer collaboration. I wish there was more of it.

Now I’m going to reproduce some of the posts about this performance that were posted by musicians, so I don’t lose them. I think they’re fascinating.

I especially like this one, by the clarinetist in Stout’s band. I like watching him in the video, and thinking about the things he says in this post, about how he was caught up in the music and the whole thing of it.

LAST WEEKEND, APRIL 15-17, 2011, was the tenth anniversary of an annual east coast Swing dance event, the Washington, D.C. Lindy Exchange, or DCLX. I was very fortunate to perform there with Jonathan Stout’s Campus Five and full Orchestra. It was one of the most outstanding experiences of my performing career.

Most Swing dance events are fun but, from a musical standpoint, can be a little disappointing. The tunes we play tend to be very similar melodically, the acoustic environment ranges from horrible to mediocre (the sound guys often make things worse), the musicians’ performances can be inconsistent, and most of the 20 to 30 year old participants would just as soon dance to a metronome. A live band, even a good big band, is more a status symbol for the festival promoters than a critical attraction. After all, the dancers listen mostly to rock, rap, and hip-hop in the car, not vintage jazz. But they always are polite enough to thank us with applause at the end of the night because most are good hearted.

Jonathan rarely calls me to play clarinet with the small group—only when all of his tenor sax players are unavailable. Once before, last March, he included me on a traveling gig. So I was stunned when he asked me to fly to Washington and also, at the end of June, to perform at Lincoln Center in New York City. As it turned out both are big band gigs and, on those, he features me on clarinet.

I almost turned down the DCLX trip. Jonathan forgot to book my flight until two days before the departure date. I asked him whether he really needed me and he said a couple of his usual guys were unable to go so, yes, he needed me. Typically that kind of “admission” is his way of manipulating me into doing what he wants but this time I knew he was being truthful; his arsenal of soloists was pretty thin.

We flew into Baltimore because it’s less expensive than flying to Washington, D.C. and, at 12:30 a.m., we drove an hour to Rockville, Maryland. On the way Jonathan explained we would participate in a so-called battle of the bands. As he described it, the “competition” would be very indirect and the other band was nothing we should worry about; just a group of young upstarts from Seattle who played music from the late 1920s, a passing fad and less than ideal for serious dancers. “No problem”, he said. “We’ll mop the floor with them.”

***

The two small groups performed Friday night. We went first and played for ninety minutes, then we packed up as Glenn Crytzer and his Syncopators held forth. Well, yes, Glenn is younger than 30 and, yes, his group did play some tunes from the late ‘Twenties. But they also played tunes from the ‘Thirties and early ‘Forties. And his musicians were of about the same age as ours. And they were tight and rehearsed and musical and sounded good.

Our trumpet player, Jim Zeigler, drummer, Paul Lines, bass player, Wally Hersom, and I stuck around to listen. We stayed for an hour. And, as Glenn’s musicians had done with us, we poked our heads through the stage curtain and applauded and cheered them on. They deserved it.

The next day it rained so both big bands rehearsed in a large wooden school building in a beautiful wooded neighborhood near Glen Echo, Maryland. Crytzer’s band already was at work in another room when we arrived. They sounded very good and played a wide variety of music.

Both big bands consisted of half local musicians and half regulars. Jonathan spent 45 minutes running down a few of our more critical numbers. The lack of dynamics and sloppy section work in the horn and sax sections left him unfazed; the guys would pull it all together at the performance that evening. As for dynamics, well, Jonathan’s band performs at two levels: Loud and louder. He says that’s what dancers want.

So we went back to the hotel as Glenn’s musicians continued to rehearse in the other room.

An hour later Jonathan and I went out for a quick dinner. He seemed preoccupied; he was thinking about the upcoming performance. I asked how serious he was about competing. He said, “I want blood.”

“Blood is good,” I answered. It was clear Jonathan was dead serious despite his casual approach to preparation. I would try to add excitement to our group.

***

Both big bands set up on the same stage. The dance began at 9 o’clock and the Syncopators went first and played very well. Then it was Jonathan’s turn and our first set was, well, adequate. We were lucky because the Syncopators’ second set was little more exciting than our first and Jonathan’s choice of material for our second set was much stronger, varied, and melodic. Mercifully the horns and saxes remembered to bring down the volume behind the many clarinet solos. I was able to nail my parts and help get things swinging. The whole band started to cook. Musical excitement is contagious and I was counting on that. I suppose judges might have scored the two groups about even at that point but Jonathan had the momentum.

And then the event spokesman declared the battle was on; Glenn’s band would play a tune, Jonathan’s would answer, then Glenn, then Jonathan, and finally both bands would duke it out on Jumpin’ At The Woodside and Fats Waller’s Honeysuckle Rose.

At that point the music took on an intensity I never have experienced at a dance festival. All the musicians played harder and the vocalists sang better and the dancers began to notice. About fifty had stopped dancing during Jonathan’s second set and crowded up to the stage. As the music swung on, more and more couples stopped dancing and moved toward the bandstand. Soon hundreds, all but a couple of dozen people at the very back of the hall, had stopped dancing and began to cheer for the soloists. That was unprecedented. Today’s Swing dancers go to dance, not listen. Music is merely fuel for their feet.

The music pounded on. Glenn had found a young blond guy from Wisconsin who played tenor and baritone sax. His solos on both instruments knocked me out and, on that final tune, Honeysuckle, he really belted out a winner on tenor. I doubt more than a few people realized it.

But Glenn’s secret weapon was his bass player because he doubled on Sousaphone. So, in the middle of Honeysuckle, Glenn traded his guitar for a banjo and the bass player picked up the Sousaphone. The crowd went nuts. They always are suckers for unusual instruments like tubas, washboards, bones, and spoons; it’s a cheap old trick from Vaudeville dog acts. But then half of Glenn’s band dropped out and the rest slid into a Dixieland chorus: Trumpet, trombone, clarinet, and rhythm section. Now that was showmanship!

Jonathan roared back with an unrehearsed sax section riff and the section played it slightly wrong. Somewhere along the line he tossed me a second solo. Then the drummers went head to head and our drummer, Paul Lines, played a final volley that took down the house. Glenn’s band answered with a great riff from Benny Goodman’s Fletcher Henderson arrangement they had practiced that afternoon. Jonathan shot back with a riff from Count Basie’s The King and, at the bridge, I threw in Benny’s short 1938 solo. Both bands together blasted out a final chorus and the place broke out into hysteria.

Who won the battle?

Does it really matter? Music is not a competitive sport.

My father was at the Palomar Ballroom in Los Angeles that famous night in August 1935 when Benny Goodman made history and launched the Swing era. Our experience in Glen Echo, Maryland came as close to that as is possible today. It was an electrifying night for the musicians and the dancers.

I have played many times on the Johnny Carson Show and several other TV shows. I performed several times at Carnegie Hall. I’ve played jazz festivals. I have worked with genuine jazz stars. My groups usually received standing ovations. But Saturday night in Glen Echo was one of only two occasions where I experienced that surge of electricity you feel when you know your music has impacted an entire venue. It will stand out in my memory as a unique example of the immense power jazz possesses to bring anyone to a level of profound joy.

This entry was posted on Friday, April 22nd, 2011 at 8:24 am

the power of jazz: dclx 2011

This is a piece about musicians playing for dancers, by Glenn Crytzer:

Great Jazz vs. Great Jazz for Dancing

Hi Jazz Fans,I once overheard a bandleader say about playing for dancers “I just do whatever I do and if people don’t like it, fuck’em.” This was in the same breath that he was complaining that the better dancers didn’t come out to hear his band play. D’oh.

Musicians and dancers aren’t always on the same page about what makes a good set. Sometimes my fellow musicians or my fellow dancers will walk away from a set thinking it was killer, and I will walk away pretty disappointed with the way it turned out. People usually attribute this to “never being satisfied” or “being too hard on yourself” but I think it really has to do with having two sets of benchmarks for success.

Having experience as both a musician and a dancer I notice that I hear different things from dancers than what I hear from musicians in describing a “good” set. Here are things some I often hear:

Musicians’ List

• I did creative things with my solos, I had a chance to “open up” as a soloist

• The other musicians inspired me to do different things

• The group dynamic had a lot of play back and forth – musicians were feeding off of each other

• The band was really swingin’ – ie everyone was playing well and we were locked in together to a particular groove

• People were cheering, clapping.

• People told me they liked it.

• Dancers were “jamming”

• People bought CDs/merchDancers’ List

• The music had a good variety of tempos

• The average tempo was not too fast

• The songs weren’t too long (longer than 4 min is usually too long)

• The songs didn’t all sound the same

• There was good “energy” to the songs

• The band hit cool breaks, endings, and licks together.

• I recognized some of the songs

• The band’s style was swing (or trad depending on your taste)

• I felt like I was interacting with the live music

• The band didn’t take forever between songs and didn’t talk unintelligibly on the mic.Pretty different! So why do dancers and musicians see it so differently? I think there are several things that we use as markers for a successful set on both sides that are misleading:

Glenn’s list of myths debunked

• “Doing creative things with your solos” is meaningless to dancers unless the things that you do are creative in a way that inspires dancing. Playing a bunch of really fast harmonically interesting passages is often lost on dancers, but a big wail on one note from a trumpet never misses.

• “The band was really swingin’” is not the same as “the band was really playing swing.” A band can swing without playing swing music; a band can play swing music without swinging. A combination of the two is important for successful dance music, but the fact that the words are homonyms makes it confusing.

• “People were cheering/clapping and people told me we did a good job” isn’t necessarily a barometer of how well people liked it. People clap at the end of a show because they’re supposed to clap at the end of a show. Dancers sometimes stomp for an encore simply because they want to dance to another song, not because they were crazy about the music. It doesn’t mean it’s not flattering, or that they don’t appreciate you, but take it with a grain of salt. If they say good things about you publicly or to other people without being prompted, then you know they actually liked it. To me, having half the audience hooping and cheering and losing the other half is not a successful set.

• “Dancers were Jamming” – One jam means dancers were digging your music AND there were enough good dancers for there to be a jam. More than one jam (planned jams excluded) usually means the songs were too long and tempos were too fast, so people started jamming because the songs weren’t good for social dancing. Sometimes that’s not the case, but usually it’s pretty reliable.

• “There were a good variety of tempos and the average tempo wasn’t too fast.” The other day someone told me they were happy we’d started playing more “mid tempo” songs. First of all, backhanded compliments are pretty douchy. Second of all someone else came up to me and told me they thought the same set was too slow. This happens at pretty much every dance – not everyone’s going to be happy with the tempos on any given night of dancing whether it’s a band or a DJ. The idea is to make the majority of people at each skill level happy. If you’re not digging the tempos one night, it might be you and not the band. That said, some bands only do play fast and slow songs. If you want to present your opinion, unless you know the band leader personally, share it with the organizer. However, if you’re going to go that route, you need to share your opinion every time, good, bad, or mediocre. People most often are willing to speak up when they don’t like something, but just take it for granted when they do. When organizers only hear the negative feedback then we end up with a DJed scene because they figure people just don’t like live bands.

• “I didn’t like it ’cause the songs all sounded the same”- It’s good for a band to vary their style subtly within the repertoire however every band has their own individual voice and that’s going to add cohesion to their sound. If a band comes out and just plays head tunes all night, well I find that pretty boring too, but don’t expect a band to come out and sound like 10 of your other favorite bands that a DJ plays in a row. I’ve never heard a great dancer complain that a band played all the same style of music all night. It’s always novice dancers who make this complaint because they don’t have enough skill to hear the more subtle variations in style that the band IS making.

• “The band took forever between songs.” Some bands, many bands, take too long. They also mumble into the mic between tunes. If you’re gonna talk to people, talk TO them for a reason and make sure they can understand you, but don’t just do it to cover your lack of preparedness for the show. However, with a DJ the time is too short between songs. It’s a social dance, so be social, chat with someone. Your lack of social skills does not constitute a band leader’s crisis. That’s one of the reasons I feel like a DJed dance is really just a practice session. Practice sessions are where you’re just there to practice dancing. Social dances are for listening to the music, interacting with others, and dancing.

————

For what it’s worth, here’s the list of what makes me walk away happy from a set:Glenn’s List

• Musicians walked away feeling good about the set

• Dancers walked away feeling good about the set

• I played well personally

• I didn’t feel limited in which charts I could call by anyone on stage’s abilities

• Everyone in the band played well together and listened to one another

• Everyone read the charts well and paid attention to dynamics, endings, and other details

• Tempos were well mixed

• Styles were well mixed

• There was energy between the crowd and the band.

• People talked about the show to their friends afterward, posted on facebook/twitter/blogs, etc

• People told the promoter/organizer that they liked the show

• People bought CDs

• People told me specific things they liked about the show

• I was able to keep dancers at all skill levels engaged.————

I think the more that musicians understand what makes good dance music, and the more that dancers understand the logistics and culture of dancing to live music (which IS the culture of the lindy hop), the better the scene will get.cheers,

Glenn

(Posted 13th January 2011 Great Jazz v Great Jazz for Dancing)

I’m a bit sad to see the impression from the clarinetist that dancers would just as well want to dance to a metronome and that the band isn’t appreciated. There seems to be exactly that disconnect going on that you write about at length in this (very good) post.

I love dancing to live music and the quality of the band makes a huge difference but yeah I hadn’t even considered that I and my fellow dancers might be having a hell of a time appreciating the heck out of the band and the music with our bodies as we dance and that at the same time the band might be going through the motions and thinking we’re not paying attention to them.

To be fair the very best bands I have danced to are used to playing for dancers and can read the room and play it like a good DJ would in terms of managing the energy