Forgive the messiness of this article, please. I have a rubbish cold and I’m trying to string thoughts together, and not doing so well. But I want to wack down these ideas now before I forget. They’re not properly researched, and I apologise for that. This post has also suddenly changed tack, and goes a bit far away from my original goal: telling you guys I’m discovering Turk Murphy for the first time.

I’m never an early adopter, and I like coming to new musicians slowly, when I’m ready. So I’ve just discovered Turk Murphy. Turk Murphy was in the Yerba Buena Jazz Band, and he did some interesting work with Sesame Street, including this cool animation for ‘the Aligator King‘:

and ‘#9 Martian Beauty‘:

Turk Murphy was friend with Bud Luckey, the animator for these films. He was also friends with Ward Kimball, a Disney animator, and trombonist for the Firehouse Five. I tend to lump the Firehouse Five Plus Two in with this group of New Orleans revivalists, though I think I favour the YBJB. Kimball is responsible for the 1969 animated short ‘It’s Tough to be a Bird‘:

I’ve been following other San Francisco musicians in a haphazard way for quite a long time, but I haven’t really put much thought into them. Let’s look at them in context.

These guys are pretty much all white (though they did do work with people like Bunk Johnson), and they’re really what we could call ‘New Orleans revivalists’, or even ‘moldy figs’ (which I’ve written about before: here are some links). They’re all really good musicians, and the music they make is exciting and fun. I don’t play them that often, though, as I find they lack that little twist that 1920s New Orleans jazz and blues, and event later NOLA based music holds. It’s almost as though this New Orleans revivalist stuff ignores the complexity of jazz and blues and focusses on the fluffy, light hearted stuff. I know that’s unfair. And I know that though many of these bands are associated with stuff like the Walt Disney Studios and Sesame Street, these relationships are actually more likely to signal a complex relationship with power and politics than ‘silly cartoon fluff’. They use humour and talk to children in a way that is utterly subversive, and really quite clever. Particularly in the case of the Children’s Television Workshop. But I find this stuff just doesn’t combine that seed of pathos that makes comedy and humour really work. Particularly in the blues.

But then, maybe I’m just not paying attention.

Lu Watters, of course, was a musician with a long history in San Francisco jazz, and the Yerba Buena Jazz Band, though formed in the late 30s, is still an important band in jazz history (this somewhat irritating story about the history of the band is useful). The San Francisco Traditional Jazz Foundation kicked off in about 1939 (reference: SFTJ website), and the Yerba Buena band was central to this association. Lu Watters was a trumpeter and band leader, founding the Yerba Buena Jazz Band, setting up the original gigs at the Dawn Club, and then pushing the group on to other shows and recordings. Watters was nuts for King Oliver’s Creole Band, and much of the YBJB’s early stuff echoed Oliver’s band’s recordings. YBJB members included singer and banjoist Clancy Hayes, clarinetist Bob Helm, trumpeter Bob Scobey, trombonist Turk Murphy, tubist/bassist Dick Lammi. The band broke up in the mid 50s, but reformed for one album in 1964. Later on (and here I’m a little fuzzy – I’m so tired of wading through the awful jazz ‘journalism’ that sets out these histories) the Yerba Buena Stompers stepped up, and that band featured Duke Heitger, whose name should mean something to fans of modern day hot jazz. Dood’s got game.

In the 1960s and 70s many of the San Francisco jazz musicians were loosely (or even closely) associated with anti-nuclear power and anti-development causes, particularly the development of the (never built) Bodega Bay Nuclear power plant on the San Andreas Fault and Bodega Bay, 50 miles north of San Francisco. Interestingly, the 1964 album ‘Blues over Bodega’ was recorded by the (reformed) Yerba Buena Jazz Band and features Barbara Dane, prominent protest singer and blues singer:

The founding of the anti-nuclear power movement in San Francisco (and California) is popularly attributed to the Bodega Bay protest

I don’t know much about this at all, but I think that the blues revival in the 1960s is inextricably linked to the counter culture movement and general rejection of mass-produced pop culture in America at the time, particularly in San Francisco.

I’d be curious to see just how close the relationship between this movement and the New Orleans jazz revival scene in San Francisco really was. Today I tend to associate the Australia hot jazz scene with revivalist impulses (which assumes an even more complicated status when you consider the history of jazz in Australia), but not with particularly lefty or progressive politics. It’s difficult to speak of an ‘Australian’ hot jazz scene, for the most part, as each city has quite different local culture and politics. I’ve a book here about it that I need to read, but I can’t get past the bullshit racist language and terrible ‘jazz journalism’ writing style.

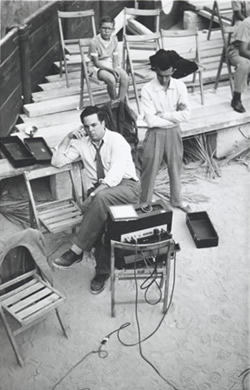

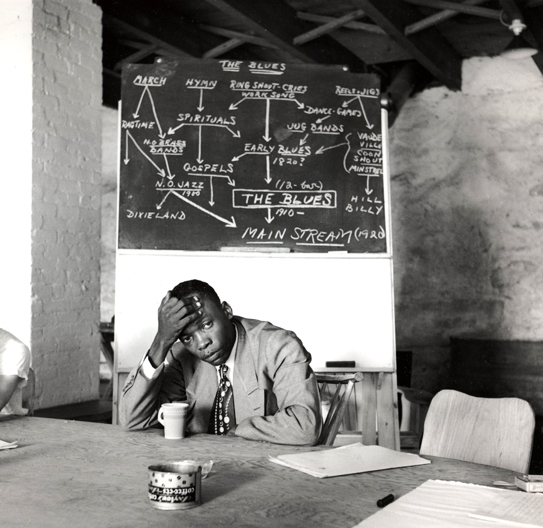

(That’s Marshall Stearns there.)

I’m quite interested in the way these ‘revivalists’ researched past masters and then hunted them down in person. That’s pretty much how the lindy hop revival came about – dancers in the 80s researched past masters and then hunted them down. There are all sorts of complicated issues of power and race at work here. White jazz fans hunting down black musicians… hmm. I’m sure – I know – they meant well. But I’m not sure they were really aware of the complex patterns of power and privilege at work in their activities.

(That’s Alan Lomax recording in Spain in 1952, from CulturalEquity.com.)

Frederic Ramsey jr. and Charles Edward Smith wrote a book called Jazzmen (1939) which is important in jazz history because it involved research into jazz history, and later led to a series of scholarships for the researchers, some of which were associated with Folkway records, which is now of course owned by the Smithsonian. This research in the 50s in particular reminds me of the Lomax work.

While I’m on the topic, I want to mention two other interesting examples of white historians and jazz music and dance.

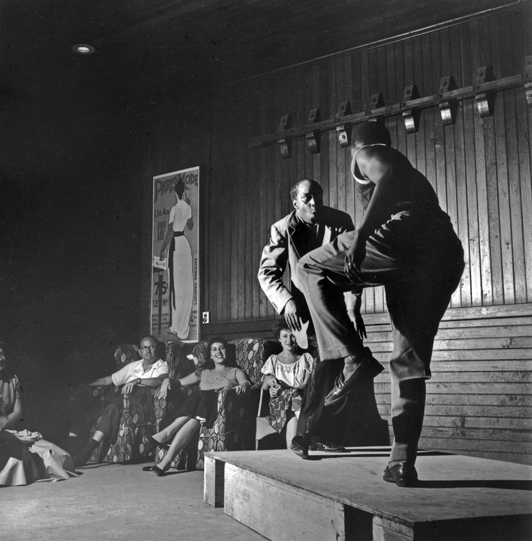

One: Clemens Kalischer‘s photos of Al and Leon from 1951:

of John Lee Hooker in 1951:

and of Marshall Stearns at the Music Inn in 1951:

led me to this story about the Music Inn, a project founded by Stephanie and Philip Barber, but prompted by Marshal Stearns (and of course I always get a bit cranky about the absence of his wife, Jean, from these sorts of histories). The Music Inn was pretty much a big musical party in the country, hosted by rich white patrons. Reminds me a bit of the stuff that happened just outside Melbourne at Heide House, except with music and dance rather than visual arts. Apparently there’s a film about Music Inn, but I haven’t seen it or looked for it yet.

I don’t know anything about Music Inn beyond the stuff in these links, and I need to chase it up. I think I need to revisit Stearns and Stearns’ book Jazz Dance just in case.

Two:

This Roger tilton film ‘Jazz Dance’:

features Al Minns and Leon James (and lots of other important jazz figures), and is positioned as a sort of historical record of ‘jazz’ music and dance.

I don’t know anything about this film at all, besides what’s on the youtube page, but I suspect some interesting things are going on.

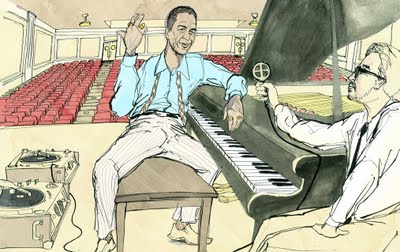

(This drawing by Brett Affrunti is an illustration for a UTNE Reader story about the recordings Jelly Roll Morton did with Alan Lomax in 1938 for the Library of Congress.)

All this research into jazz music and dance history by enthusiastic white men in the 50s (and 80s) of course, is marked by some really interesting responses from the musicians and dancers themselves. Bunk Johnson, contacted by Ramsey and Smith, was a notorious liar, fabricating not only his birthdate but various other ‘facts’ as well. Jelly Roll Morton, stalked by Lomax and recorded by the Smithsonian, was also quite good at decorating the truth. And my favourite story is of course about Al Minns and Leon James, spinning a whole heap of awesomely bullshit stories about the Savoy and Harlem nightlife for Marshall Stearns. Not to mention Al Minns’ own description of the Swedish Mafia chasing him down in the 80s.

I do like it that all this desperately earnest research by (moderately exploitative) white researchers desperate to capture and pin under glass the ‘original jazz’ was derailed by the tactics of artists who’d lived through segregation and hardcore American racism. I’ve written about it before. It reminds me so much of cake walk, and the long tradition in black dance of sending real meaning underground, and peppering the surface with a fair dose of derision and mocking.

While I do sound quite critical and a bit narky about this well-meaning research, I don’t really mean to be. As I’ve realised in reading about 1950s jazz music and dance ‘ethnographies’, this research was motivated by largely egalitarian, liberal principles. Many of the patrons and researchers involved realised that their high opinion of this art – music, dance, whatevs – was not shared by their largely racist and conservative peers. They repeatedly ran up against the belief that jazz was ‘common’, that (black) music and dance culture was less valuable than white, and that their interest in jazz culture was misguided. As that Music Inn article notes, this was made clearest in the simplest ways: they couldn’t find beds for visiting artists in segregated hotels because those artists were black.

So I think there are lots of interesting things going on here. As I’ve said about a million billion times before, I feel a real tension between my own interest in historical recreation and revival and my awareness of my own privilege. A recent misunderstanding on twitter has made me even more committed to pointing out that while I regard archival footage and older dancers as ‘resources’ for my own research and dance work, this is a relationship of absolute respect. I am aware of the power dynamics at work here. I know that I make money (though very little of it) from the creative work (mostly choreography) of dancers who were exploited in the 1920s, 30s and 40s. But I am also very strict with myself about acknowledging my sources, about promoting projects like the Lindy Hoppers’ Fund, and about remembering the social and cultural context of this music and dance that I love so much. Finally, I also take care not to position these artists simply as powerless victims of the historian-pillagers of revivalism. All those lies, all that misdirection, all that meaning-gone-underground reminds me that power is complex.

Side note: I’m currently working my way through a documentary film called ‘Black Power Mixtape‘ which features footage of black American activists taken by Swedish filmmakers in the 1960s:

You had me at the Alligator King. I’ve watched it three times already.

Fantastic post. I’m a new dancer, but I very early on noted the scarcity of black dancers in the Los Angeles lindy scene. This has always vaguely disturbed me – reconciling my excitement and burgeoning love for this dance and community with my growing awareness of its complex history in the context of race and power, and my own small part in its continuing “gentrification.” Appreciated reading your much more nuanced pondering of all this – especially since I have yet to actually discuss any of this with my fellow dancers.

And thanks for the tip about Black Power Mixtape! Must check that out!