[EDIT 13/6/13: It makes me very sad that this post is still relevant. It’s been linked up again, by a few different people around the place, because those people are having bad times with arseholes in their dance scenes. So I think it’s worth bumping this post again. This is such heartbreaking stuff to talk about. But we have to. We HAVE to.

Please, if you’re in strife and need some help, call one of the lines I’ve listed below. And if you want to change things in your own scene, start working on constructive plans with women, not for them. We don’t need no white knights, here. And if you’re in a bad way, and need some help, I know that services like Beyond Blue here in Australia can help if you’re having trouble with anxiety and/or depression. And god knows the only sensible response to this issue is sadness.]

[EDIT 4/4/12: I receive emails about this post, or comments on this post every couple of weeks. I published it almost a year ago. It breaks my heart that this issue is still one we need to address.

Please, if you need help, don’t hesitate to call someone. Doesn’t matter whether something happened years ago or this morning – there are people who have got your back. Give them a call.

- If you’re in America, RAINN can link you up with a hotline. Or call 1800 656 HOPE.

- If you’re in Australia, NSW Rape Crisis Centre has good links, or phone 1800 737 732.

- If you’re in the UK, Rape Crisis has good links, or call 0808 802 99 99 (not 24 hours, though).

If you’re in Canada, Europe, Japan, Korea, Singapore, or somewhere else, please do google ‘rape help line’.]

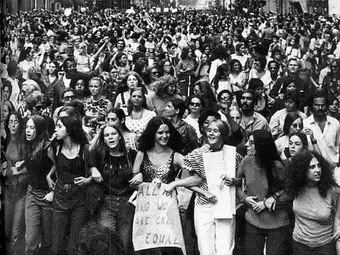

It was inevitable, really. But my thinking about slutwalk and my thinking about dance have finally gotten together in my brainz and become the Difficult Conversation About Sexual Violence in Swing Dance Communities. Despite my mixed feelings about slutwalk, it has meant that I’ve had more conversations about gender, violence, safety and community since it hit the media than I have in years and years. And most of those conversations have been with dancers who do not openly identify as feminist, or who aren’t otherwise politically engaged. To me, this is a marvellous thing.

Tim linked me up with this article about slutwalk by Jacinda Woodhead and Stephanie Convery, which links in turn to 4523.0 – Sexual Assault in Australia: A Statistical Overview, 2004, a 2004 ABS report on sexual assault in Australia. If you’ve been paying attention, most of the information in the report is depressingly familiar, yet in direct counterpoint to the myths surrounding sexual assault circulated in mainstream discourse. Key points for my post today are summed up on page 13 of this report:

For most victims of sexual assault reported to the police, the perpetrator is likely to be known to them. The most commonly reported location where the offence occurs is a residential setting.

This point is expanded on pg 24:

- All available data sources indicate that over half of perpetrators of sexual assault are known to their victims. NCSS 2002 estimated that 52% of all adult victims knew the offenders in the most recent incident in the previous 12 months; 58% of female victims and 19% of male victims knew the offenders.

- The most commonly reported location of sexual assault is residential, often the victim’s own home.

It’s important to note that these are reported assaults, and that most assaults are not reported to the police at all. The report continues (pg 13-14):

There is evidence that most victims of sexual assault do not report the crime to police, and that many do not access the services available to provide support. Factors affecting the decision to report sexual assault include the closeness of the victim-offender relationship and the victim’s perception of the seriousness of the crime.

Victims are more likely to report sexual assault to police if: the perpetrator was a stranger; the victim was physically injured; or the victim was born in Australia.

The ABS report also points out (on pg 32) that in assaults in the last 12 months, 60% did not involve alcohol, 38% did. The figures don’t indicate where the perpetrator or victim had consumed alcohol.

The following facts are also noted:

In Women’s Safety Survey 1996 data :

- approximately one in six Australian women (16%) reported that they had experienced sexual assault at some time since the age of 15

- one in six Australian women (15%) reported that they had been stalked during their lifetime

- one in four Australian women (27%) reported that they had experienced sexual harassment in the previous 12 months.

It’s important to point out that men are also victims of sexual violence, though at lower rates, and with far smaller numbers of assaults reported.

It’s also important to remember that ‘sexual violence’ and sexually threatening behaviour is broader than the conventionally heterosexual definition of penetrative intercourse (where the p3nis penetrates the vag1na). So ‘rape’ or ‘assault’ leaks out beyond the heterosexual notion of ‘sex’. To talk about sexual assault, we need to expand our definitions of rape, and of sexual activity and of violence. This then allows us to talk about men as victims of assault (as well as perpetrators), and men as the victims of male and female violence. I think it’s also important to remember that the sexual abuse of children constitutes rape.

So, then, a useful point from the slutwalk protests and discussions around the place:

What you (male or female) wear is not the reason you were assaulted.

and

Yes means yes and no means no, whatever we wear, wherever we go.

and

Most assaults happen in the home (or domestic spaces), not darkened alleys, and most people are raped/assaulted by people they know. In most instances there’s no alcohol involved.

How does all this relate to dancing?

Sexual assault and harassment happens in the lindy hop world

Firstly, there have been sexual assaults in dance scenes all over the world. Most are no doubt not reported. I have personally heard of one incidence in Melbourne, where community discussion of the assault was not terribly useful, largely phrased in terms of a woman ‘being violated’. I don’t know if she knew her assailant. Perhaps the most widely discussed (in the United States and online) sex offence was Bill Borgida’s arrest for possession of illegal pornography (specifically pornography featuring children). This was discussed at length in the Yehoodi thread ‘Bill Borgida: Two Counts: Child Porn’. Borgida responded to the issue with a public letter to ‘the dance community’, also posted on Yehoodi, in the thread A letter to the Dance Community from Bill Borgida.

This second issue is particularly disturbing, as Borgida travelled internationally, visiting Australia as well as many other countries. I knew him quite well, and my own feelings about this issue are fraught. I felt furious, upset, sad, hurt, betrayed, guilty, anxious, angry, confused. I want nothing more to do with him, ever. But the responses in the open letter thread on Yehoodi are more complex. Many people feel still support him and forgive him. I cannot.

Most significantly, I’ve been stunned by many people’s regard for the possession of prnography as a relatively victimless crime. There seems to be a vast chasm between consumption and production in this thinking. They cannot seem to grasp the idea that possessing and consuming pornography featuring children is at once supporting a market for the material and endorsing its production. The production is beyond reprehensible: this is sexual assault. Of children. Many, many children, over many years. All recorded and distributed for adults’ pleasure. Possession of this material is equivalent to producing it.

I don’t want to suggest that using prnography is the same as raping, or that using prn leads to raping people. It doesn’t. But the way we use prn and produce prn, and our attitudes towards sexual activities are informed by broader issues of gender and power and identity. So sexual assault becomes a symptom of, or expression of, a perpetrator’s ideas or feelings about power. Having it, not having it, taking it, fighting it. Child abuse, then, is about perpetrators with power harming less powerful people – children. Using child prnography is about finding violent power sexually exciting. These sorts of ideas and feelings about power and other people do not stay safely partitioned in your ‘private life’.

I’ve also been suprised by many dancers’ willingness to separate what happens on the dance floor from what people do off the dance floor, or in their ‘private lives’. I can’t. I increasingly believe that the way we dance reflects our broader ideas about the world, and about the way we feel about other people. For example, the rough or inconsiderate lead is frequently socially inept or clumsy and disrespectful of women off the dance floor. I am unwilling to disassociate dance from cultural context.

But I shouldn’t be surprised. Thinking about people you know – and like – committing acts of sexualised violence on other people you know – and like! – is really difficult. It’s so difficult and horrifying that many of us would just rather not think about it at all. If we make it disappear by defining rape in a way that simply ignores most assaults, the problem become manageable and less frightening. It won’t happen to me if I don’t wear a short skirt, if I drive a car, if I don’t drink, if I don’t talk to strangers. My wife/sister/friend/lover/daughter is safe if I walk her to her car or I fight off an attacker in the street.

Dancers do not challenge sexually inappropriate behaviour often enough.

I also frequently come across the sentiment in dance discourse (online and face to face) that swing dancers are ‘good people’. Yes, many of them are. But I am certain that many of them are also capable of, and do perpetrate, sexual assault. I think this is a difficult idea to talk about in dancing. So much of what we do is dependent upon the idea that we are all ‘good people’ who just want to ‘enjoy themselves’ in ‘harmless dancing’. We also trust the person we are dancing with, who we touch, intimately, and who we work with, creatively. I find it deeply disturbing to think about being in a closed embrace with someone who is capable of sexual violence.

There is very little violence at social dance events. I’ve only ever witnessed one incidence, in extreme circumstances. But I have witnessed many incidences of bullying and sexual harassment. There are endless stories about leads who physically handle women into lifts or air steps in dangerous contexts. Or followers who do not take responsibility for their own balance or kicks. We’ve all got a story about the guy with the tent in his pants who presses too closely to uncomfortable women in the blues room. We’ve all got a story about that guy who always ‘accidentally’ does the boob swipe in class or on the dance floor. Many of us also have stories about women who perpetrate an unwelcome ‘beaver clamp’ in the blues room or spend too much time draped over men off the dance floor. Though it’s difficult to compare men’s and women’s inappropriate behaviour, and they work in different ways within a broader context of patriarchal society.

Most disturbingly, swing dance culture advocates tolerance of these sorts of actions. We are told, repeatedly that we should never say no to a dance. Women in particular are encouraged in most scenes to wait for a man to ask her to dance, and then to be so grateful for the dance she should tolerate all sorts of inappropriate behaviour just to be dancing. Women are also discouraged from dancing with other women, where they might have the opportunity to dance in a clearly nonsexual partnership. And, just as worryingly, it is very, very rare for a man to talk to his friends or other women about women’s inappropriate behaviour. Men are expected a) to enjoy sexual attention, and b) to not feel threatened by women. I mean, when I wrote, explicitly and in detail about particular men in the post Hot Male Bodies, was I crossing a line? Was that inappropriate?

This raises yet another issue in dance. What does sexualised dancing mean? Is this public or private space? Is it appropriate to take something from the dance floor and then decontextualise it, take it away from the dancer themselves? Dancers seem to negotiate this stuff every day in sophisticated ways. I mean, there are millions of amateur clips of performances, but it’s much less common to find footage of social dancing. It is as though most of us have agreed that social dancing is ‘private’, even when it’s conducted in the exact same spaces with the exact same people. If it is regarded as private, then, is that why we have so much difficulty making clear, hardline condemnations of sexual harassment on the dance floor – the tentpants, boobswipes and beaverclamps which make us so uneasy, but are so unlikely to be openly and immediately censured? After all, our broader societies find it so difficult to legislate domestic violence and sexual assault…

There are covert methods for dealing with this sexual harassment and bullying. We tee up a friend to quickly intervene and take us to the dance floor if a ‘dodgy’ person approaches. We learn to physically ‘block’ a partner who wants to get too close. We hide ourselves in a crowd to make approach from ‘undesirables’ difficult.

I’ve also learnt how to deal with men want to bully me in a professional setting. I’ve figured out, for example, how to a) not let male DJs (and they are always male) bully me into letting them DJ when and how they want when I am working to an event coordinator’s brief, b) not feel obliged to hire difficult or bullying DJs, c) make sure everyone pays entry fee when they are required to, regardless of ‘status’, d) not to end up being overworked and exploited by event organisers (either by their design or their incompetence).

It’s important to note that most volunteers at dance events are women. And that we are engaged at all levels in the management and running of events. We have also managed to develop non-confrontational methods for dealing with difficult people. Unfortunately, these methods are usually ‘invisible’, so avoiding the public demonstrations of women’s conflict resolution skills. Their invisibility also maintains the idea that swing scenes are always ‘nice’ and ‘friendly’ and ‘safe’.

I’m framing these ‘everyday’ instances of sexually inappropriate behaviour as sexual harassment and bullying for a reason. Let’s remember those points from the ABS data. Most perpetrators of sexual assault are known to their victims. If we insist that sexual violence only occurs in public places, is only perpetrated by ‘strangers’ with weapons while women risk their safety wear revealing clothes on the street, we make real rapes invisible. We hide the fact that we are more likely to be assaulted by the man who has driven us home, walked us to our door, gone out to dinner with us many times before. We also discourage women from speaking up about inappropriate actions. Don’t make a scene – the Uppity Woman will not get another dance! It’s not sexual harassment if a man continually touches your breasts on the dance floor?! In this context, the sexual assault by a known person in your own home is also disappeared. The perpetrator doesn’t believe he’s raped someone. The victim is left wondering what she did to deserve this. After all, she’s learnt that she’s not to speak up if she’s touched in a way she doesn’t like or want.

So what are we to do?

This is all bloody depressing. It’s fucking horrible to think about my dance community this way. I do not want to think about the idea that people I know and dance with or share a room with, assault or harass people. I hate the thought that I knew and travelled and danced with Bill Borgida. But I’m certain he’s not the only person who has done these sorts of things. It’s not statistically possible. It’s like last night’s episode of 4Corners about live animal trade, A Bloody Business (Mon 30th May 2011). These things are happening in my community. I’m participating in their continuing by not asking about it, by not looking, by not watching. And, awfully, sexual assault and harassment can happen to me or to people I know and care about. Someone I know could do these things to me. Sexual harassment and assault are a real, immediate, visible part of my life.

So, really, what are we to do? What can we do?

Firstly, I think it’s important to think about broader social and cultural context. This is why I bang on about women dancing and the way we think about women dancing. Do we encourage passivity, acceptance, submission in women dancers? I think we do. Do we also encourage, or at least enable, inappropriate behaviour by men? I think we do. I also think we need to talk about these issues. And to do what we can. For me, that’s meant learning to lead. But it’s also meant asking questions about things like unequal divisions of labour in the dance community. Who is always working the door at social events? Do they actually want to be sitting there all night? Who does get paid and who doesn’t? Why don’t people get paid?

Secondly, I think that going on and on and on about the shitty stuff, getting angrier and angrier and feeling more and more upset without doing something is disempowering. It weakens us with despair. So we need to a) pay attention and ask questions, b) talk about this stuff and then, most importantly, c) DO SOMETHING. I’m a big fan of small, localised change and action. A rally was cool for getting us talking. But it’s not enough. We need to saddle up, friends.

There are things we can do.

I want to talk about how we get home from dancing, because it’s about getting from ‘private’ place to ‘public’ places. This is a tricky one. We’re out late at night, usually on public transport or walking to our cars alone. We’re out with a large group of people, some we know well, many we don’t. All sorts of people come to swing dances. Many of them are socially awkward or inept. Many of them already ring our internal discomfort alarms and have us avoid dancing with them. We go out to drinks or meals after dancing with large groups of people, many we only know by first name even though we see them every week. At the end of the night, how do we get to our cars, to our homes?

My usual instinct is to get a ride with someone in a car, or to organise a group to go via public transport, and then to call Dave so he can meet me at the station. But is it really such a good idea to get a ride with someone from dancing? Even if you’ve seen them every week for a year, what do you really know about them? This is where it gets really tricky. I don’t want to advocate mistrusting every man just because they’re a man. This is why it’s attractive to think ‘only strangers are a threat’. It’s impossible to be wary all the time. And being wary all the time is disempowering. If we’re spending all our time being angry or worrying about being raped, we don’t have time to be excellently powerful and strong. But it also makes sense to think about safety and to be safe. To be aware of our surroundings.

Perhaps a solution is to organise groups of women to travel home together, and to have clear sets of rules for how you get home. No one walks to the station or their car alone. Send a text message to keep in contact. Or to get help. I’m not sure how this should work, but I think we should organise these sorts of things! Sometimes it’s hard to get to know other women at dancing well enough to develop these sorts of support networks and practices. We dance mostly with men in class and socially, we women don’t develop solid peer networks of trust and confidence in each other. Although I have always found that leading, and doing solo stuff with women socially is a key part of developing creative and personal relationships with other women in dancing.

But this talk about ‘getting home’ is still accepting that myth that sexual assault is only done by strangers, only happens in public places, late at night. We should think about the idea that sexual assaults happen at dance events. When we walk to the toilets through the gardens to the toilets at the back of the hall. In the toilets. In the carpark. In dressing rooms. In empty ‘breakout’ rooms at late night dances. At the reception desk while everyone is in dance classes.

These thoughts are far, far more frightening than the idea that we’re only at risk for that 40 minutes on our way from dance to home.

We need to think about safety at dances. And, much more importantly, about dance culture.

So here is what I do.

- I pay attention to the people at the dance venue. Who is in the room? Who are they watching? How are they acting? If a man slips into the blues venue on Friday night, asking me to “hold the door” which is usually locked, do I know him? If I don’t, where does he go? It’s harder to pay attention to the whole room when I’m dancing than when I’m DJing. When I’m DJing, I’m constantly watching the people in the room. I notice who sits and does nothing. I see the guys who watch women dance and move and sit and talk and walk. I recognise the difference between a sort of general interest and an unnervingly close attention. I take note of the men who boobswipe or target the less confident women, the newer women dancers, the younger women. I pay attention to men who only dance with these type of women or who stand too close to them. There’s often a reason these men are avoided by women dancers who’ve been around. Sometimes it’s just social awkwardness that sets them apart. But sometimes it’s a nameless, discomforting creepiness.

- I call people on their bullshit. This makes me less popular. But what the fuck. I’m not 20. I don’t need everyone to be my friend. And if I see some guy picking up a shyer, less confident girl and tossing her into some sort of bullshit lift, I’m going to say to him “Stop that.” And I’ll say to her “He’ll hurt you. Don’t let him do that.” Then I’ll make sure I talk to her later, about other stuff, so she knows I’m not shitty with her. I won’t (for the most part) let some dickhead chuck me around. I will call attention to a boobswipe, even it’s to make a joke, even if it’s an accidental boobswipe. I’ll also call guys on sexist jokes or crude, cruel comments. I try to be gentle, but I’m often quite confrontational. This does mean that I’m not going to be asked to dance by some men, many of whom are the ‘best dancers’ or high status. But who gives a shit? And why would I want to dance with that arsehat anyway?

- I’m also equally determined to appreciate and show my appreciation for positive, excellent behaviour and attitudes. I think it’s like applauding awesome boogie backs when you want to encourage solo dance. It’s easy to get angry. But it’s healthier to get constructive. Carrot rather than stick. This is where men come in handy. If we want men to be the most excellent men they can be, we need excellent men to model excellent behaviour. On the dance floor and off it. Men should call other men on bullshit talk or actions. They needn’t be stroppy. Jokes are very powerful. More importantly, men are excellent, and when they do excellent things and we all applaud them for their metaphoric boogie backs, we are showing other men that being excellent is a lucrative business. We need to change cultures of masculinity, not ridicule men. The challenge, then, becomes how we go about doing this. How, for example, should men express their sexual interest to women? Or appreciate a particularly fine frame on the dance floor? How should men and women do heterosexuality in a positive, empowering ways? We’re creative people, right? We can figure this out.

- Dance classes are important. Dance classes are a key point in the socialising of new dancers. How do the male lead and female follower model appropriate behaviour on and off the dance floor? Who does most of the talking in class? Who interrupts who, and how often, and how? Who makes the jokes? Who’s the butt of the joke? What type of jokes are they? Is there sexualised talk or joking? What sort of language do teachers use to refer to gender or to leading and following? What analogies do they use? How do they dress? How old are they? What are their relative ages? Where are they teaching? What material are they teaching? Who are the dancers they mention?

I could go on and on and on with this. But I think it’s important to figure out ways of making this work in your own life, and own social context. But, mostly, we need to be Excellent To Each Other.

We also need to be aware of the fact that dance scenes are not all flowers and ponies. Bad shit does happen, and we should do something about it.

I’m of course thinking about

I’m of course thinking about  I’ve just had a quick look but I CAN’T find that interesting study a Victorian university group did recently where they found that if women felt safe cycling in a city, then the numbers of cyclists in that city over all were higher. I was telling this story to some hardcore environmentalist/sustainable energy types at a party the other week, and they were all “Oh shit, I’d never thought of that!” And I was thinking ‘That’s because you’re over-achieving, able bodied, young, male engineers living in well-serviced cities who dismiss feminism as ‘something for women’.’ But I didn’t say that out loud. Instead I laboured through a gentle (and brief) point that environmental movements have to be socially sustainable as well as environmentally sustainable. I wanted to talk about how birth control for women in developing countries is directly related to environmentally sustainable development in those same countries, but I didn’t.

I’ve just had a quick look but I CAN’T find that interesting study a Victorian university group did recently where they found that if women felt safe cycling in a city, then the numbers of cyclists in that city over all were higher. I was telling this story to some hardcore environmentalist/sustainable energy types at a party the other week, and they were all “Oh shit, I’d never thought of that!” And I was thinking ‘That’s because you’re over-achieving, able bodied, young, male engineers living in well-serviced cities who dismiss feminism as ‘something for women’.’ But I didn’t say that out loud. Instead I laboured through a gentle (and brief) point that environmental movements have to be socially sustainable as well as environmentally sustainable. I wanted to talk about how birth control for women in developing countries is directly related to environmentally sustainable development in those same countries, but I didn’t.

Last Monday I did my first hip hop class. I went to a studio we’ve been using for our solo jazz practice and late night dances, and I went because I was curious, but mostly because I like going to the studio. The studio is run by a young man and his friends, and it’s in the guts of the city, in the Chinatown bit. They run lots of classes and workshops (almost all in street dances like hip hop or house or locking), see lots and lots and lots of students through the door, and are generally treated as a sort of drop-in social space as well as a class venue. Most of the students are ‘Asian’, and many are international university students. ‘Asian’ is one of those difficultly broad terms, and I don’t think it’s that useful in this context: these kids are from all over China, Hong Kong, South-East Asia, Japan, Korea and beyond. A lot of younger kids use the studio space – younger as in high school – and it really feels like a well-used space.

Last Monday I did my first hip hop class. I went to a studio we’ve been using for our solo jazz practice and late night dances, and I went because I was curious, but mostly because I like going to the studio. The studio is run by a young man and his friends, and it’s in the guts of the city, in the Chinatown bit. They run lots of classes and workshops (almost all in street dances like hip hop or house or locking), see lots and lots and lots of students through the door, and are generally treated as a sort of drop-in social space as well as a class venue. Most of the students are ‘Asian’, and many are international university students. ‘Asian’ is one of those difficultly broad terms, and I don’t think it’s that useful in this context: these kids are from all over China, Hong Kong, South-East Asia, Japan, Korea and beyond. A lot of younger kids use the studio space – younger as in high school – and it really feels like a well-used space.

Now I don’t have much patience with psychoanalysis as a tool for analysing film and performance. I don’t think it works, mostly because it boils everything down to sex, and I think that this approach tells us a lot more about 19th century middle class Austrian men than about cinema. But I do think there are some interesting starting points, here. And I want to apply them to dance. Because that is what I do. I’m also interested in the way vernacular dances – on-stage and off – allow the audiences and performers to interact, in a way that cinema does not. In a dance performance, the sexualised body (be it male or female) is capable of physically, verbally and discursively interacting with the audience whose gaze they’ve invited. I think this adds a really interesting and exciting element to the fairly dull model of visual pleasure.

Now I don’t have much patience with psychoanalysis as a tool for analysing film and performance. I don’t think it works, mostly because it boils everything down to sex, and I think that this approach tells us a lot more about 19th century middle class Austrian men than about cinema. But I do think there are some interesting starting points, here. And I want to apply them to dance. Because that is what I do. I’m also interested in the way vernacular dances – on-stage and off – allow the audiences and performers to interact, in a way that cinema does not. In a dance performance, the sexualised body (be it male or female) is capable of physically, verbally and discursively interacting with the audience whose gaze they’ve invited. I think this adds a really interesting and exciting element to the fairly dull model of visual pleasure.