[note]This was a post on the facey, which I’ve started writing up here.[/]

Remind me to write up a report on how our new reporting and preventing sexual harassment and accidents process went at LBW.

Short version: it worked.

Mid-length version: we put together a door handbook, reporting forms, and a process for reporting incidents. We ‘trained’ managers in the process, and we let volunteers know about the process via the handbook, email, and in person talk.

Long version: how online discussions, reports of assaults made by very brave women and girls, and getting angry and upset led to the development of policies, of material codes and rules, and then practical processes and documents. A success story.

Things we needed:

- An online version of our code of conduct, easily accessible from one click on event website, and well publicised on facebook.

- A brief paper version of the code printed on the back of the event program which was packed into registrants’ envelopes.

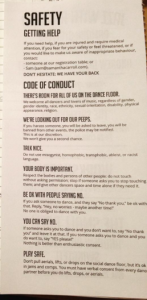

- A full version of the code printed and put into the event handbook.

- Paper incident report forms in the event handbook.

- A process for making reports (including a quiet place to do the, who should do them, and how, etc etc).

Most importantly, we needed good will from all the volunteers, staff, and managers. And that was the easy bit. Everyone was really keen to make this work, and really just saw this as an extension of our Swing Dance Sydney rules:

- Look after your partner

- Look after the music

- Look after yourself

What a lovely group of people.

This is by no means a finished project, but it’s actually turned out to be a very interesting and productive one.

Packing the code of conduct (on the back of the program) into registrants’ envelopes.

A first version of our event handbook, which contains lots of things, including: event program in plain text, door count sheets, cash count sheets, incident report forms, code of conduct, guide to identifying wrist bands, various paper signs, etc etc. All in one central folder.

There were two copies of this handbook, and each has a plastic slip on the front for adding notes or action items when handing over shifts or responsibilities.

A first draft of our incident report form, which drew on examples provided by lots of useful people who work in places that have decent reporting processes for accidents, etc.

A first draft of our incident report form, which drew on examples provided by lots of useful people who work in places that have decent reporting processes for accidents, etc.

These forms are in our event handbook.

The longer version of our code of conduct, in paper form. It explains what counts as sexual harassment, and s.h. is just part of the ’emergency’ and ‘incident’ part of the handbook, after what to do if there’s a fire.

The longer version of our code of conduct, in paper form. It explains what counts as sexual harassment, and s.h. is just part of the ’emergency’ and ‘incident’ part of the handbook, after what to do if there’s a fire.

The paper version of our code of conduct on the back of an event program. Which is available at the door at events, in registrants’ rego packs, and as a promotional item distributed to venues in the week or two before the event.

The paper version of our code of conduct on the back of an event program. Which is available at the door at events, in registrants’ rego packs, and as a promotional item distributed to venues in the week or two before the event.

Having it so readily available is an attempt to normalise this sort of talk and material. So ordinary that everyone has read it.

[Note] That was the original post. Then there were some comments. Here are some of them.[/]

Tal Engel: Can you elaborate on the phrase “it worked”? Are there any incidents you’re comfortable discussing where the system came into play?

We had no reports (thankfully, but also – maybe we had incidents but no reports?), so I can’t talk about that issue.

But I think ‘it worked’ relates mostly to the ‘consciousness raising’ part of the exercise, to quote old school activism. So by having lots of people involved in the process, from stuffing envelopes to handling a handbook, we gave people access to the code, and to the process. We demystified our process, but we also demystified sexual assault and harassment a bit. I hope.

I also wanted to make it clear that these things are _all_ of our responsibilities, and something that happens in our public places between friends, not in dark car parks by strangers.

It also ‘worked’ as a practical skills development process for me, and for the rest of the group. So actually putting together a handbook took some practice and real thinking – far more than I had expected. And it took several drafts to create something more accessible. Still needs work I reckon.

It also worked as a way of engaging all the staff in thinking about events as community spaces, where problems (whether they’re someone needing a bandaid, or someone needing a quiet place to sit and talk) are solveable.

…I think one of the most effective parts of this whole process was the online discussion of this process on our facebook event page.

I just matter of factly laid out the deal. But this also dovetailed with the way I engage with people on the event fb page: prompt replies to queries, but professional in tone. I also use my real name and face on event pages (rather than the event’s home page ID), so that our events have a ‘face’ and a name behind them. This makes it easier for people to see who they’re ‘talking to’, but also says ‘hey, I respond to your concerns’, which hopefully sets up an example of how I might respond to reports of assaults.

More importantly, this public talk in a public forum also addresses the lurkers, who are the vast majority of readers. They might never post on the page, but they read how I engage, and see what I do.

I’d really, really hope that this also normalises modes of discourse for this topic. ie just as having other women leads in your scene encourage other women to lead, having someone addressing these issues clearly, personally, and professionally might also encourage similiar responses.

What I really hope is that people will do as I do when I go to an event: see the best stuff other people do and then copy shamelessly in an attempt to be as good at it as they are. So hopefully people will see what I did, steal the good bits, and improve on it all, fixing the bits I’m not good at.

Related to this ‘putting a face and name to an event’ stuff, is having badges for volunteers. It’s something for volunteers and staff to know when they’re on duty (you take it off when you’re off duty), but it’s also a clear way of identifying staff (and you need to tell punters about this). If I had more money, I’d have done Tshirts :D

Related to this ‘putting a face and name to an event’ stuff, is having badges for volunteers. It’s something for volunteers and staff to know when they’re on duty (you take it off when you’re off duty), but it’s also a clear way of identifying staff (and you need to tell punters about this). If I had more money, I’d have done Tshirts :D

I’d add that this wasn’t a particularly difficult process. It just took a while. And we had to approach it as an iterative process: where you don’t just do it and then, boom, it’s finished. You see each version as one step in an ongoing process.

I think that it was very important to be very angry and determined to do this. If I hadn’t be so angry, and if I hadn’t wanted so much to look out for my peeps, I probably would have given up ages ago.

I think this process makes it very clear that a simple code of conduct squirrelled away on a website is pretty much useless on it’s own.

Some of the most important parts of this process were:

- Having a lateral power structure (rather than a top-down power pyramid dynamic thingy), where everyone had a role to play, and power to do things and make decisions – from volunteers and people making reports to musicians and managers. To me, this is THE most important part of this process. If it’s just a boss ‘saving’ women, then we’re not changing anything; we’re reinforcing the status quo.

- Getting people involved by asking for help, by posting about my sticking points on fb (eg posting that I needed a reporting form but had no clue where to start gave me a bunch of useful comments and messages, plus actual examples of other people’s forms).

- Letting go and letting other people do stuff.

[note]After some other discussion, I got to this point…[/]

What I’d really like to do is get together with other organisers and peeps at some weekend event to talk through what we do and what they do. There’s already a very healthy network of people sharing ideas, but I want MORE!

[note]This is the bit I want to emphasise. I’ve learnt most from seeing what other people are doing. And I want MORE of it.[/]

As an example, I learnt a lot from talking to Ben Beccari about handbooks and practical emergency response stuff. He’s doing a Phd in disaster response, so he’s kind of mad skilled. I also talked to people like Liam Hogan about how the SES does stuff here. And I had examples from friends of reporting strategies (I’d better not name them in case it’s meant to be confidential :D ). I also followed up ideas with my femmo stroppo mates (like Kerryn, Zoe, Kate, Penni, Tammi, Liah, Naomi, Daniel, and MANY more) for their suggestions and ideas, which came from their big brains, and also their experience as activists at community and local levels.

…I keep adding names, but there are too many. So many people had excellent ideas.

[note]end[/]

So, that’s what I have from that post.

I’ve written about what we’ve been doing in a few other posts already:

*1. I think a code of conduct is important because it sets out your goals and ideals in plain language. I go into why codes are important in this post.

2. ‘Cultural change‘ is about changing the way we do things. The way we think about teaching and teach, the way we think about learning and learn, the way we think about social dancing and social dance, the way we think about partners and treat our partners, the way we think about ourselves and treat ourselves. All of this stuff changes what we do and think about what we do. I like to mix feminism with historical example: I have clear political goals, but I want to use and stay true to the creative and practical examples of the swing and jazz era.

3. Developing strategies for practical change means confronting men about their behaviour, training staff, and banning offenders. But in a thoughtful, organised way, not a random, ad-hoc way. Our practical actions (what we actually do) must be guided by solid thinking and a sense of consequence. We need to be safe, we need to confident, we need to be organised.

**In this one I wrote this paragraph, which really sums up my whole purpose:

There have been some scary moments, but, for the most part, it’s actually been a very exciting and positive experience. Sitting down and thinking about what we want to do, and talking about the good things we want to see has been very exciting. It makes us feel good. This is what activism is about: you start by getting angry. You do some learning, and then you start doing things which make you powerful.

***One of the most important parts of dealing with sexual harassment, is women having the confidence to speak up. To speak in public. Male perpetrators rely on women and girls being too frightened to speak up and challenge them. To tell people about the things that men are doing. They threaten women and girls into staying silent, and they rely on broader social forces which discourage women to keep them quiet.

When those women first wrote about Mitchell’s violent criminal acts on this blog, one of the responses was that they should have made private complaints, spoken to the police, been more polite. More careful.

Their speaking up was very important. Very, very important. And this is one of the reasons I’m not entirely for male feminists. I think that the very act of speaking up is a political act, and one of the key parts of being a feminist. We are told sit down and shut up. And when we stand up and say no, we are doing a radical thing.

And this is where I’ll end this post.

We have to speak up. A private email or private discussion between a woman and her attacker or an organiser is an extension of the conditions that made that assault possible in the first place. We are supposed to push issues of sex and interpersonal violence between men and women into the private sphere. It’s not supposed to be appropriate for public discussion.

In simpler terms, I know that if I send a private email to a man who is a sexual offender or one of their offenders, he’s much more likely to try to bully me, frighten me, attack me. I do my talk in public now, because it’s safer. I want witnesses. Just as I don’t ban or warn offenders in person unless I’m in a public place with plenty of witnesses.

And I know this, because it happens. So I say: speak up. Be sure you have buddies to get your back, but speak up. And by buddies, I’m saying ‘sisterhood is powerful’. This is what that expression means: when we work together, women and girls are far more powerful than most men would like to think. We can protect each other and ourselves.

And after all, that’s what all this is about: women protecting themselves and each other.